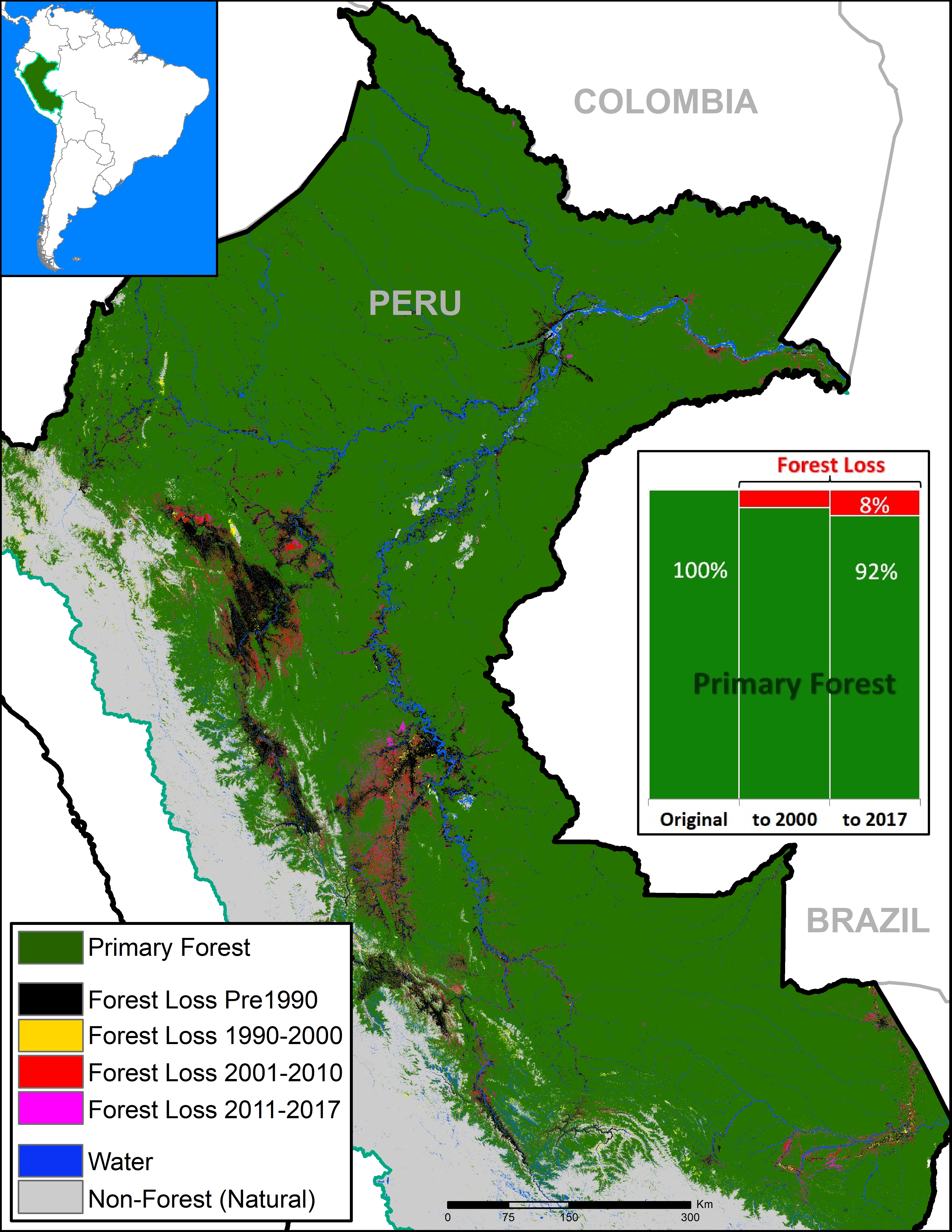

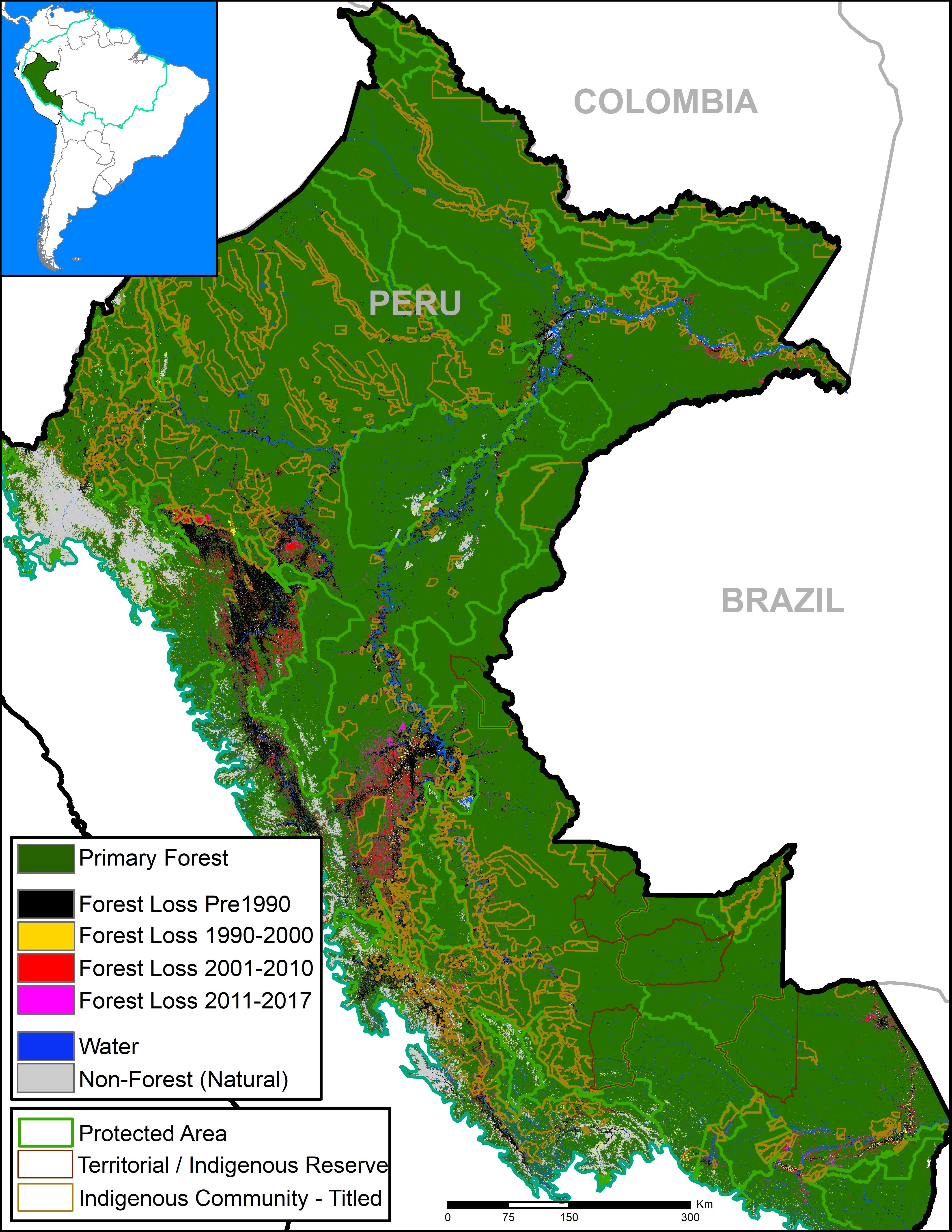

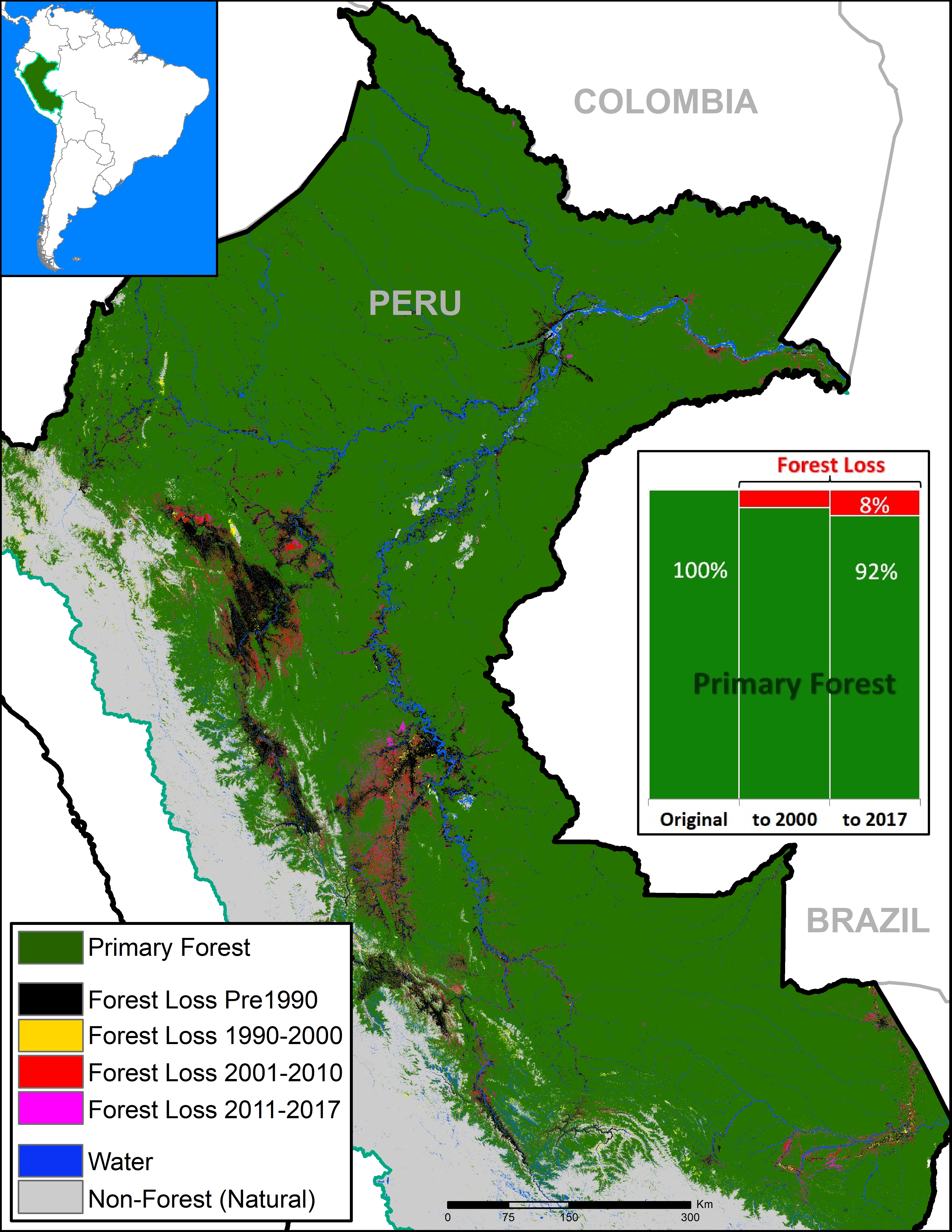

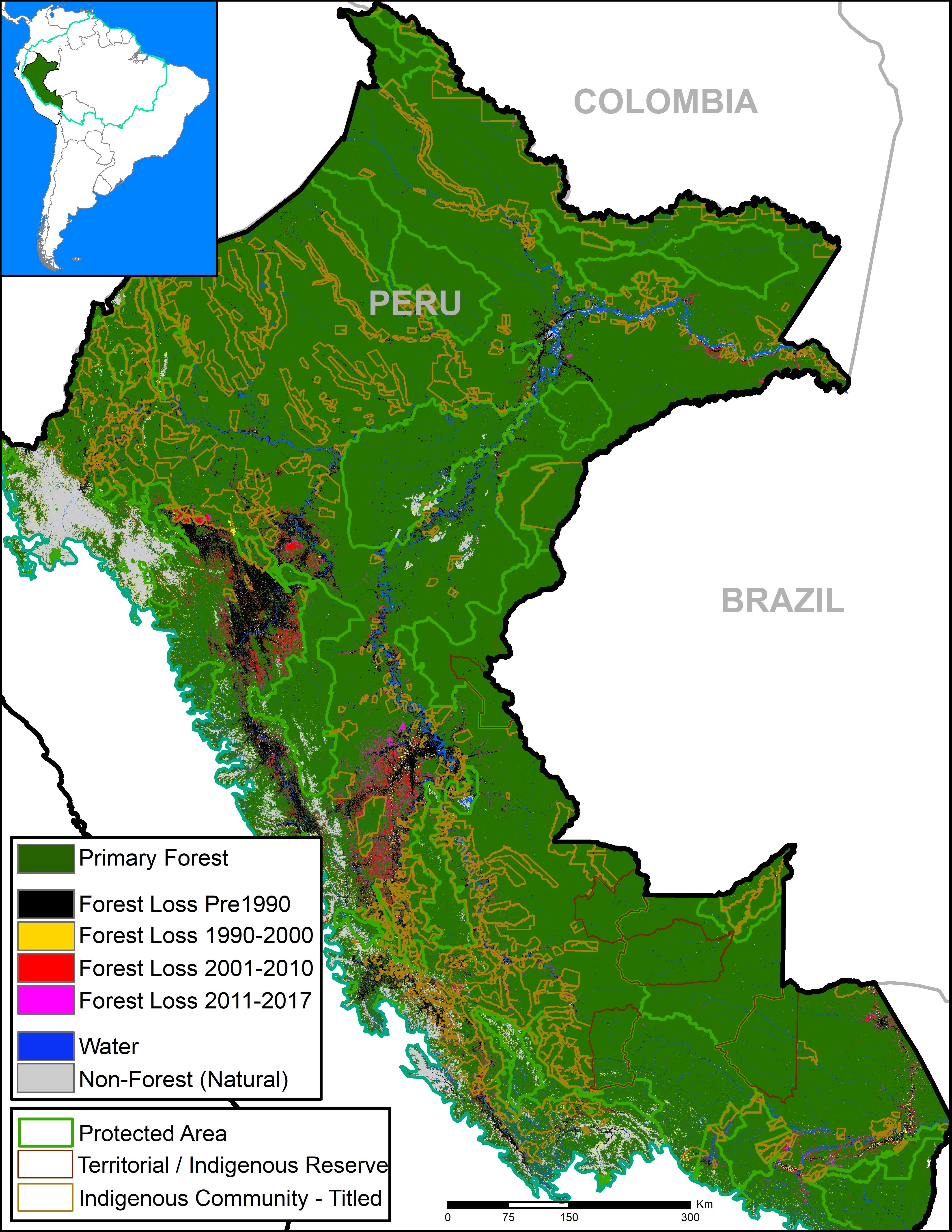

Base Map. Data: SERNANP, IBC, Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA, PNCB/MINAM, GLCF/UMD, ANA.

The primary forests of the Peruvian Amazon, the second largest stretch of the Amazon after Brazil, are steadily shrinking due to deforestation.

Here, we analyze both historic and current data to identify the patterns.

The good news: As the Base Map shows, the Peruvian Amazon is still home to extensive primary forest.* We estimate the current extent of Peruvian Amazon primary forest to be 67 million hectares (165 million acres), greater than the total area of France.

Importantly, we found that 48% of the current primary forests (32.2 million hectares) are located in officially recognized protected areas and indigenous territories (see Annex).**

The bad news: The Peruvian Amazon primary forests are steadily shrinking.

We estimate the original extent of primary forests to be 73.1 million hectares (180.6 million acres). Thus, there has been a historic loss of 6.1 million hectares (15 million acres), or 8% of the original. A third of the historic loss (2 million hectares) has occurred since 2001.

Below, we show three zooms (in GIF format) of the expanding deforestation, and shrinking primary forests, in the southern, central, and northern Peruvian Amazon.

GIF of deforestation in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Data: see Base Map

Southern Peruvian Amazon

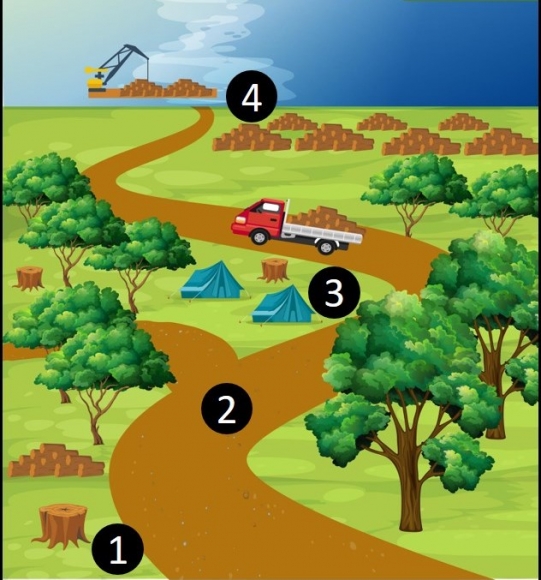

Note these three important trends in the GIF (click to enlarge):

- Increasing deforestation all along the route of the Interoceanic Highway;

- Increasing gold mining deforestation across several different fronts near the southwestern section of the highway;

- Increasing agricultural deforestation around Iberia, along the northern section of the highway near the border with Brazil.

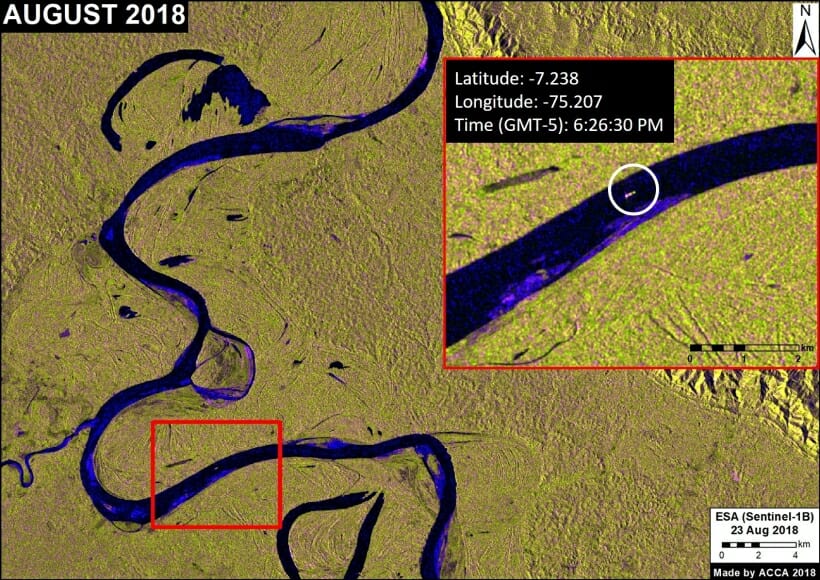

GIF of deforestation in the central Peruvian Amazon. Data: see Base Map

Central Peruvian Amazon

Note these three important trends in the GIF (click to enlarge):

- The substantial historic (pre 1990) deforestation around the cities Pucallpa and Tarapoto;

- Increasing deforestation along the road leading west from Pucallpa;

- Large-scale deforestation for oil palm plantations outside of Pucallpa and Yurimaguas.

Base Map plus protected areas and indigenous communities.

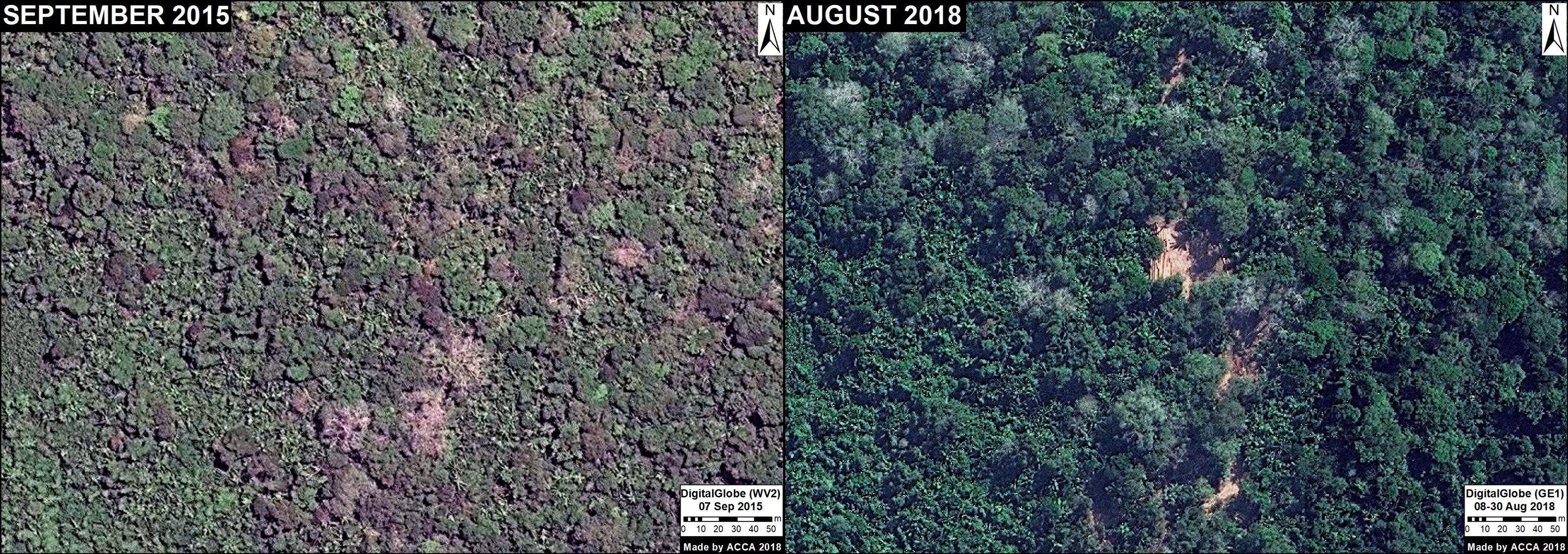

Northern Peruvian Amazon

Note these three important trends in the GIF (click to enlarge):

- The historic (pre 1990) deforestation around Iquitos;

- Increasing deforestation along the Iquitos-Nauta road;

- Large-scale deforestation for United Cacao plantation near the town of Tamshiyacu.

Base Map plus protected areas and indigenous communities. Data: SERNANP, IBC, Hansen/UMD/Google/USGS/NASA, PNCB/MINAM, GLCF/UMD, RAISG, Ministerio de Cultura.

Annex

The Base Map with three additional categories: Protected Areas, titled Native Communities, and Indigenous Reserves.

Notes

*Defining primary forest: According to the Supreme Decree (No. 018-2015-MINAGRI) approving the Regulations for Forest Management under the framework of the new 2011 Forestry Act (No. 29763), the official definition of primary forest in Peru is: “Forest with original vegetation characterized by an abundance of mature trees with species of superior or dominant canopy, which has evolved naturally.” Using methods of remote sensing, our interpretation of that definition are areas that from the earliest available image are characterized by dense closed-canopy coverage and experienced no major clearing events.

It should be emphasized that our definition of primary forest does not mean that the area is pristine. These primary forests may have been degraded by selective logging and hunting.

**Historical Peruvian Amazon primary forests: 73,188,344 hectares. Current Peruvian Amazon primary forests: 67,043,378 hectares. Of this total, 27.6% are located in designated protected areas (18.5 million hectares), 18% in titled Native Communities (12 million hectares), and 4% in Indigenous Reserves/ Territories designated for indigenous peoples in voluntary isolation (2.9 million hectares). There is some overlap between these three categories, and the final combined percentage (48%) takes this into account.

Metodology

To generate the estimate of original (historical) expanse of primary forests in the Peruvian Amazon, we combined two satellite-based data sources. First, we used data from the Global Land Cover Facility (GLCF 2014), which established a forest cover baseline as of 1990 (The GLCF products are based on the Landsat Global Land Survey collection, which were compiled for years circa 1975, 1990, 2000 and 2005). Areas with no data due to shadows and clouds were filled in with GLCF data covering 2000-2005 time frame. The historical primary forest layer was created by combining the following three GLCF data layers: “Persistent Forest,” “Forest Gain,” and “Forest Loss.” Next, we incorporated the “Hydrography” data layer generated by the Peruvian Environment Ministry (Programa Nacional de Conservación de Bosques) to avoid including water bodies. We defined the limit of the analysis as the hydrographical basin of the Amazon. We generally define “historical Peruvian Amazon primary forest” as the expanse of primary forests before the European colonization of Peru (around 1750).

To generate the estimate of current primary forests, we subtracted areas determined to experience deforestation or forest loss from 1990 to 2017. For data covering 1990-2000, we incorporated two datasets: GLCF forest loss 1990-2000 and “No Forest as of 2000” (“No Bosque al 2000”) generated by the Peruvian Environment Ministry. For data covering 2001-2016, we used annual data generated by the Peruvian Environment Ministry. Finally, for 2017, we used early warning alert data generated by the Peruvian Environment Ministry. As a result, we define current primary forests as an area of historical forest with no observable (30 meter resolution) forest loss from 1990 to 2017.

Global Land Cover Facility (GLCF) and Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC). 2014. GLCF Forest Cover Change 2000 2005, Global Land Cover Facility,University of Maryland, College Park.

Citation:

Finer M, Mamani N (2018) Shrinking Primary Forests of the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 93.