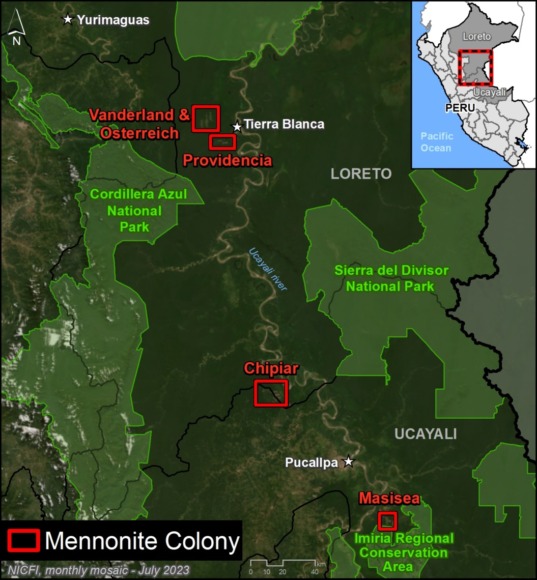

Starting in 2017, new Mennonite colonies began appearing in the Peruvian Amazon, coming from other parts of Latin America in search of new lands.

TheMennonites, a global religious group dating back to the 1600s, often require vast tracts of land to support their characteristic large-scale, industrialized agricultural activity.

In a series of reports, we have demonstrated that the Mennonites have become one of the major deforestation drivers in both the Peruvian and Bolivian Amazon.

Here, we update our findings for Peru for the most recent time period, January 2022 – August 2023.

Our objective is to provide detailed information on the magnitude of deforestation caused by the Menonites in Peru, and to identify the specific colonies where this forest loss is most active now.

Major Findings:

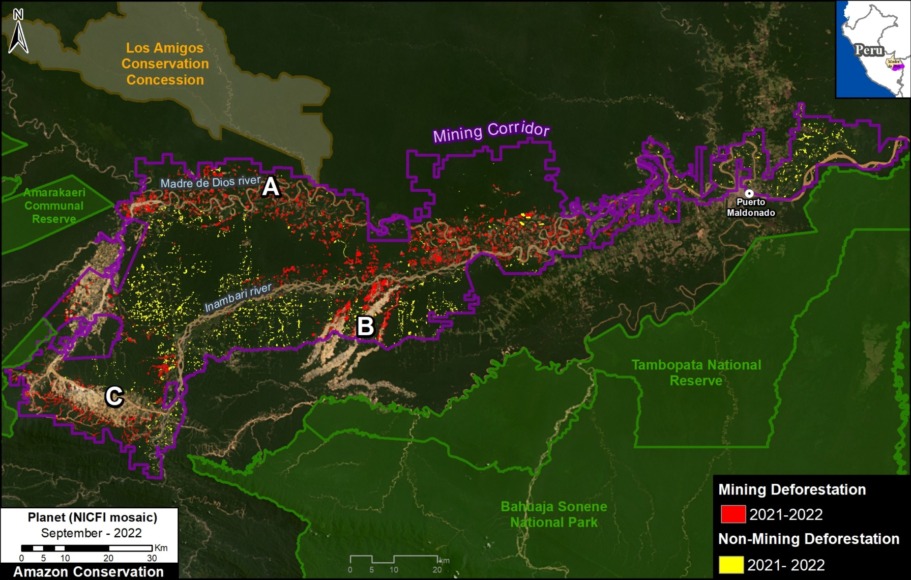

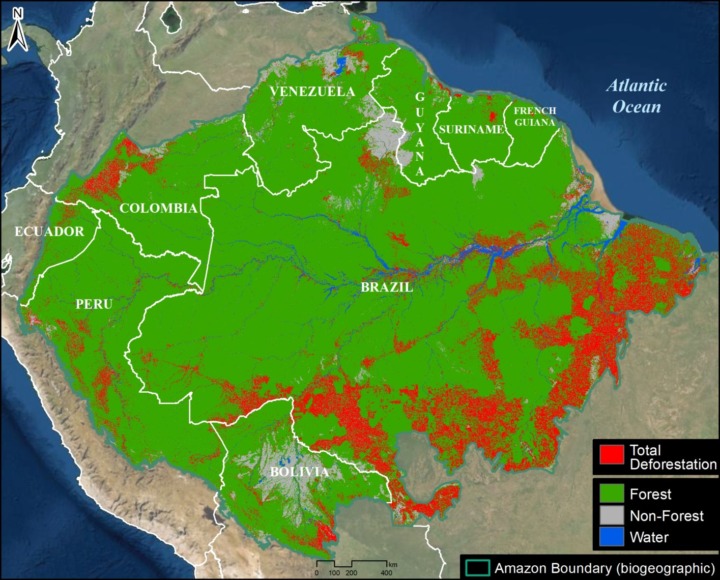

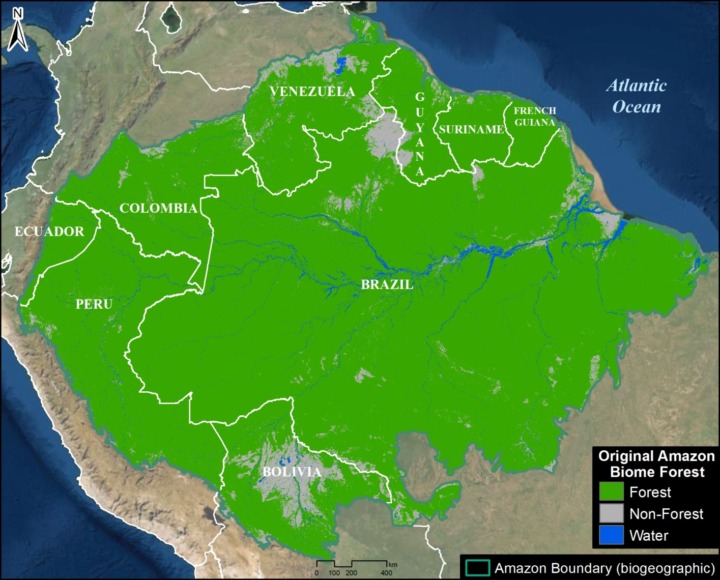

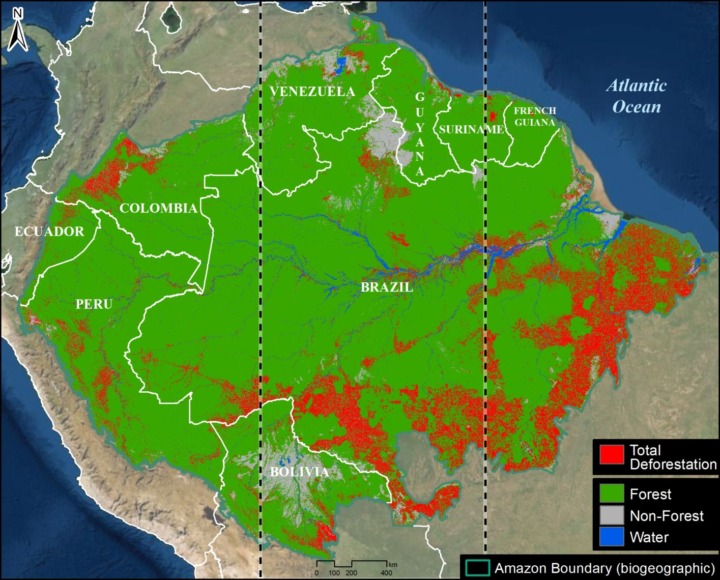

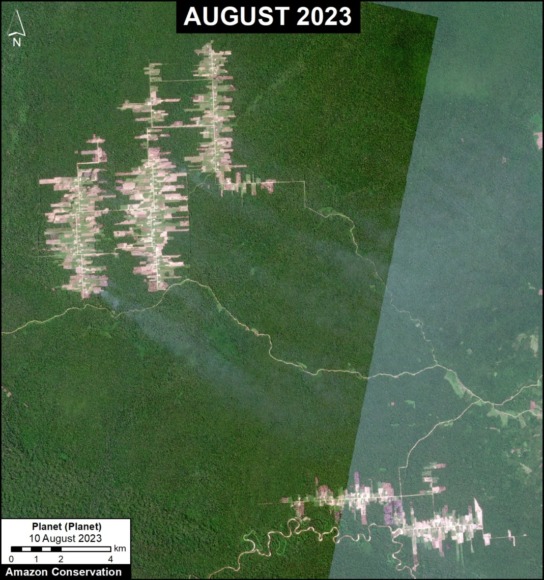

Our analysis has revealed that the Mennonites have now deforested over 7 thousand hectares (7,032 hectares, or 17,376 acres) in the five colonies established since 2017 (Vanderland, Osterreich, Providencia, Chipiar, and Masisea; see Base Map). In addition, we have documented an additional impact of more than 1,600 hectares of burned forests.

Of the total deforestation, more than a third (34.5%) has occurred in the most recent period, from January 2022 to the current date in August 2023 (2,426 hectares, or 5,995 acres).

Below, we detail the deforestation history in each colony, with an emphasis on the most recent loss.

In addition, there is mounting evidence that this massive deforestation is illegal, with numerous ongoing investigations by the Peruvian government (see the Legal Summary, below).

Deforestation in Mennonite Colonies (Peruvian Amazon)

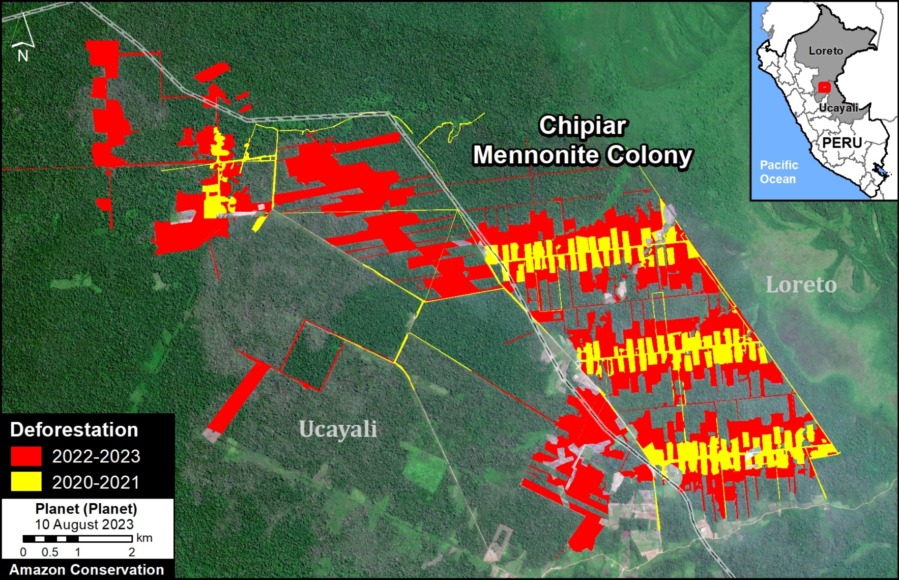

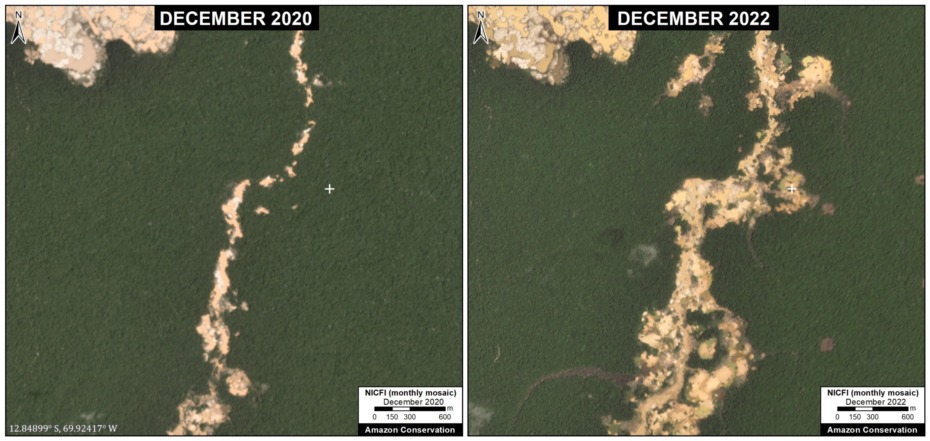

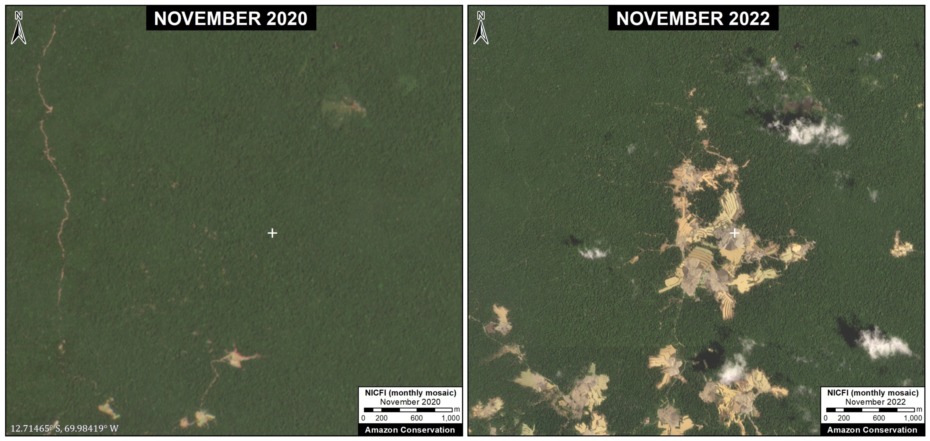

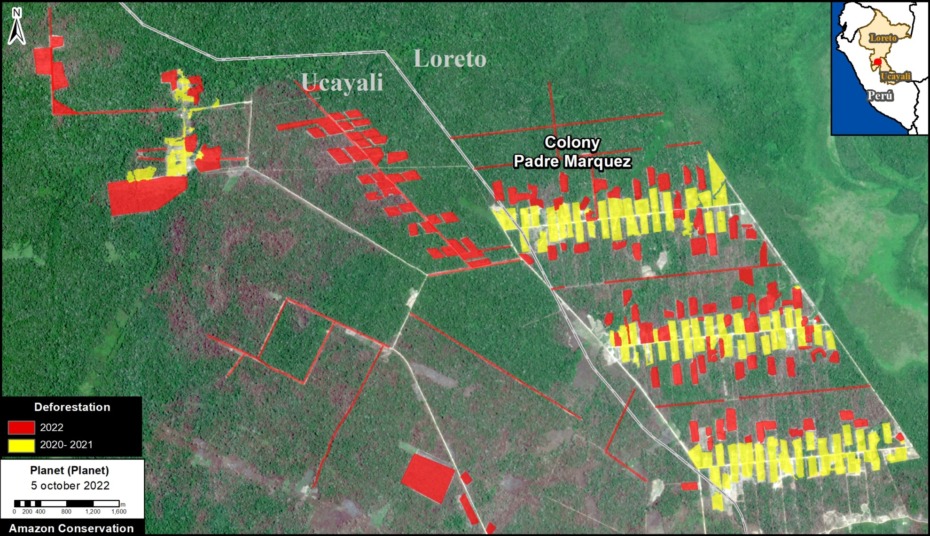

Chipiar Colony

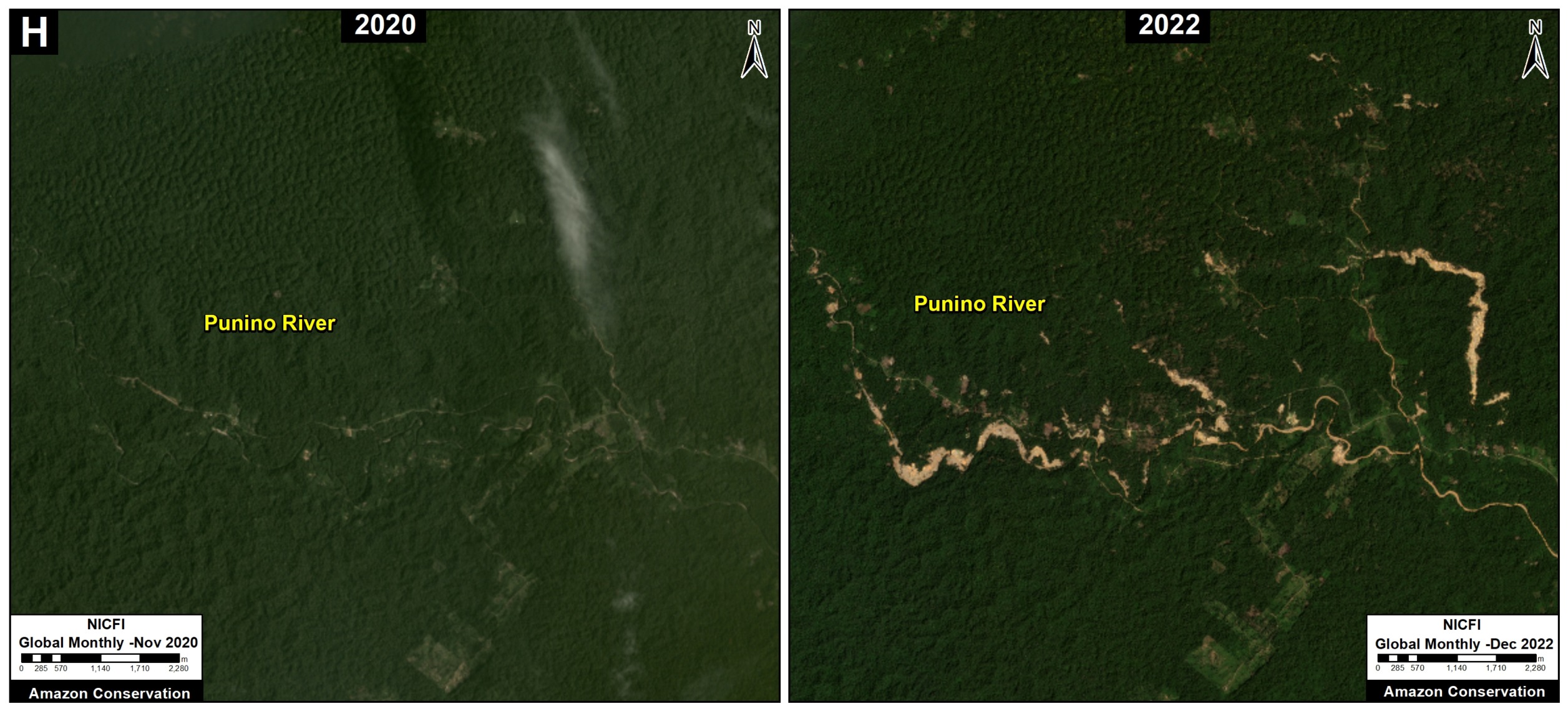

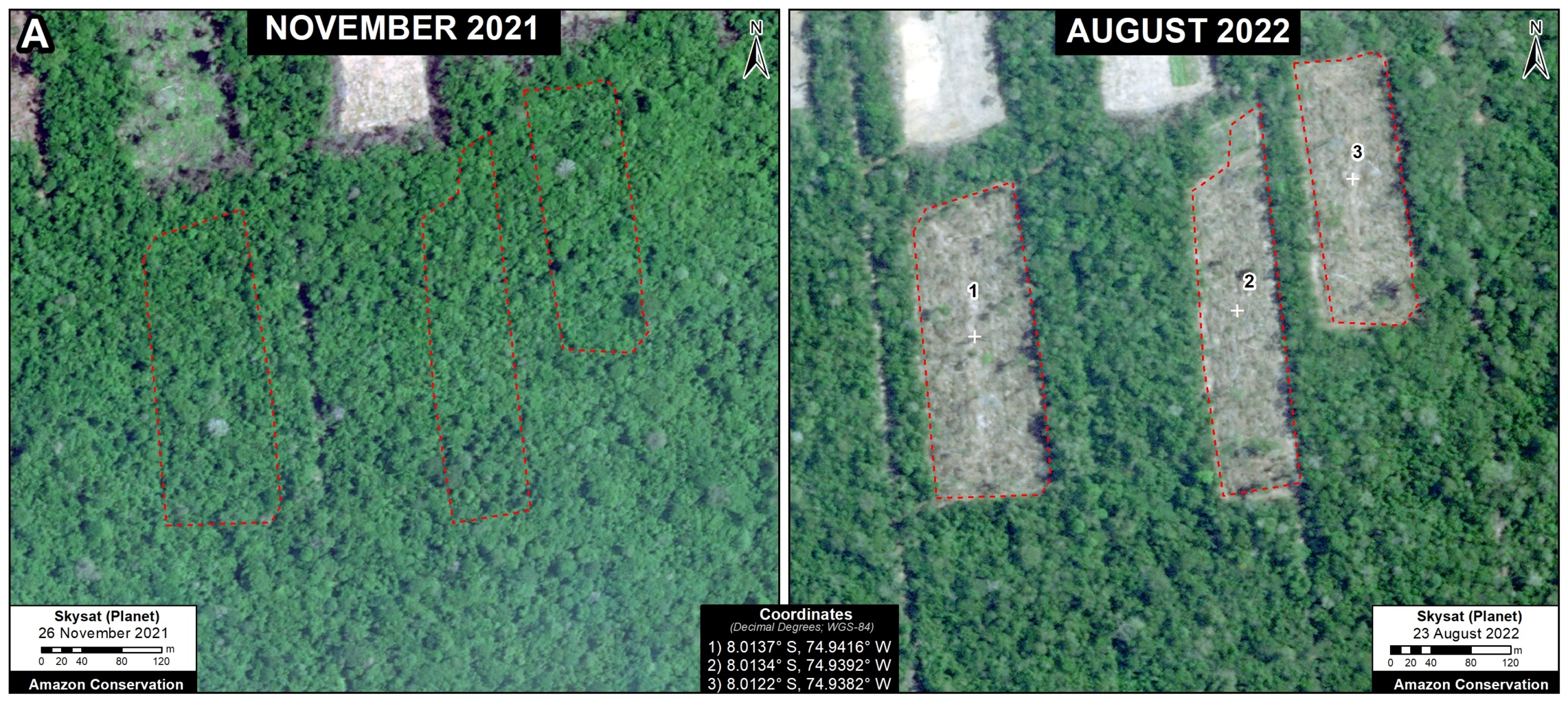

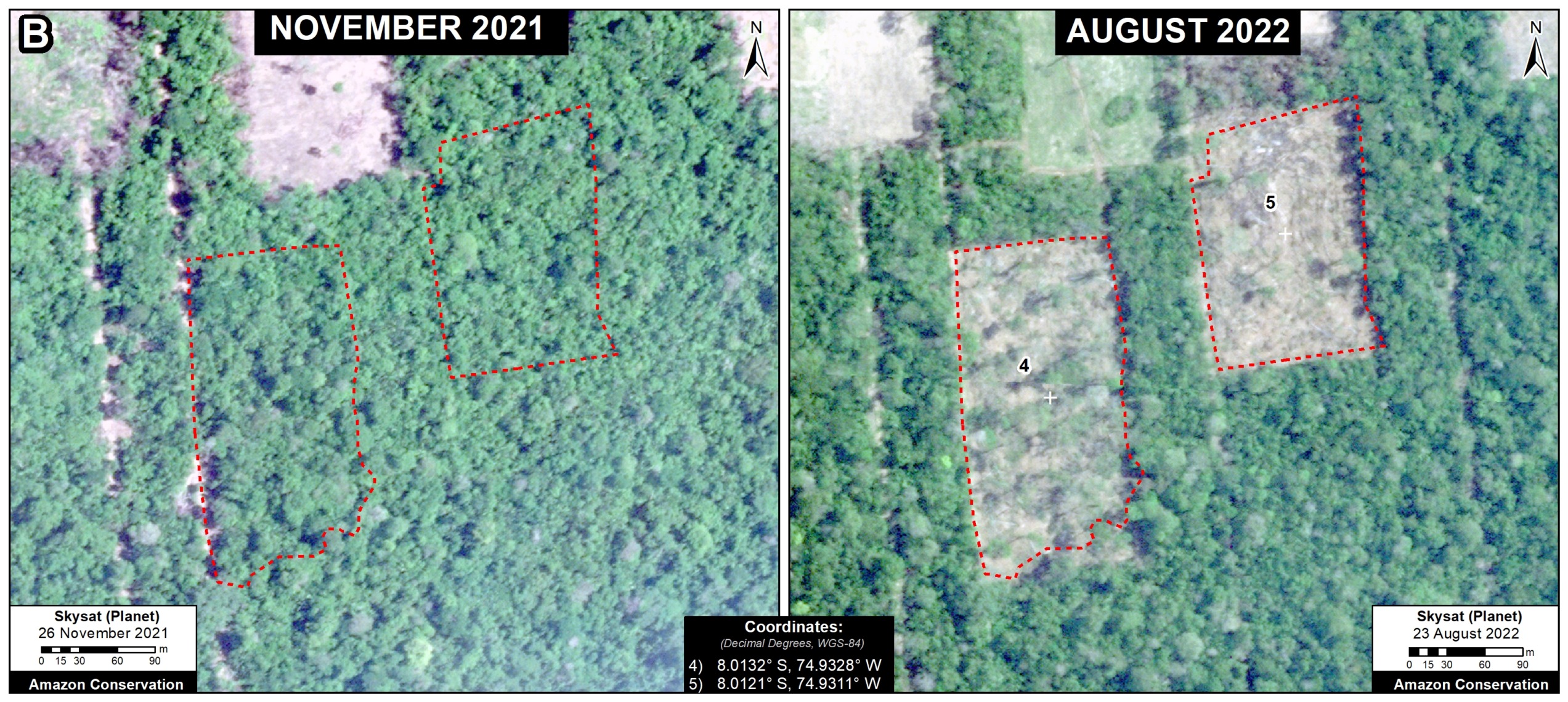

This colony is located on both sides of the border between the departments of Ucayali and Loreto, originating in the district of Padre Marquez on the Loreto side. It is the newest colony, where deforestation began in 2020. This deforestation escalated in 2021, peaked in 2022, and continues to expand in 2023.

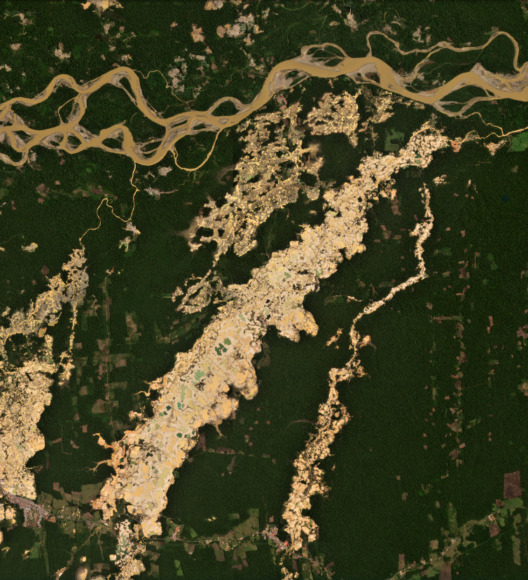

In total, we document the deforestation of 2,221 hectares in the Chipiar colony since 2020 (see image below). Much of this loss (76%) occurred in the most recent 2022 – 2023 period.

In addition, we estimate the additional degradation of 1,600 hectares by fires that have escaped from the Mennonite plantations into the surrounding forests.

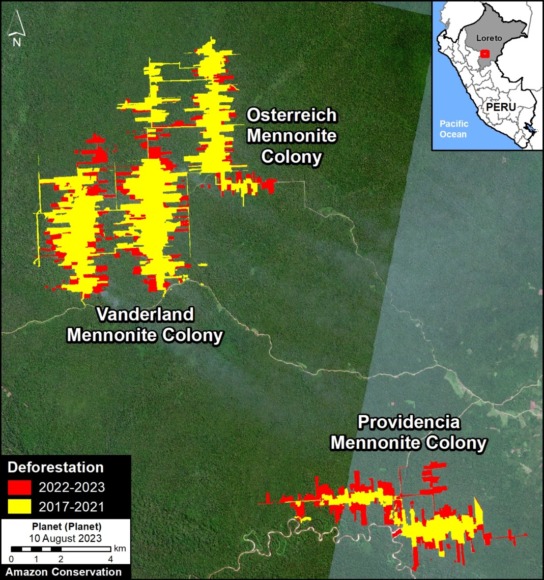

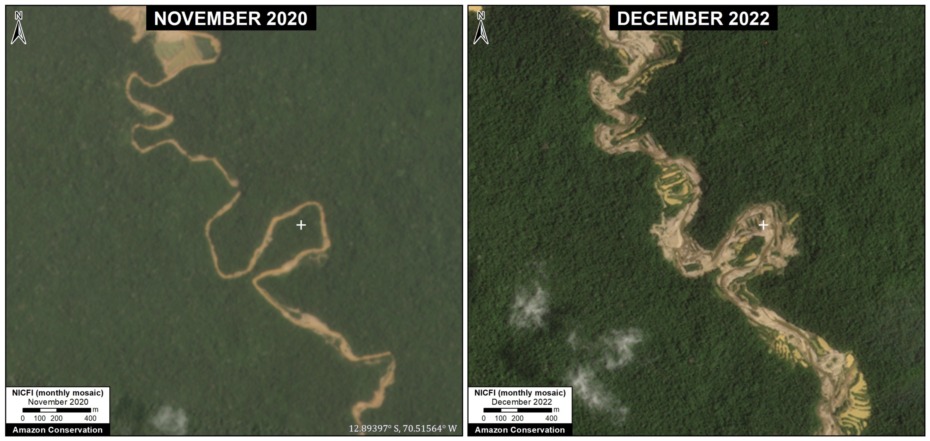

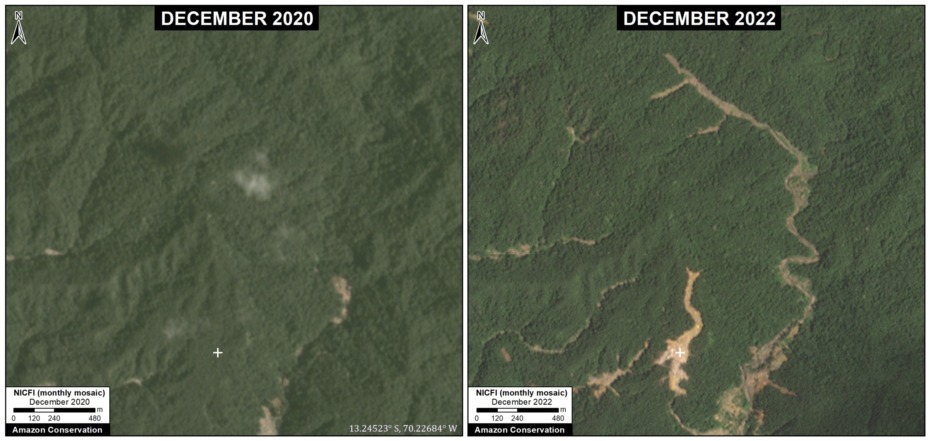

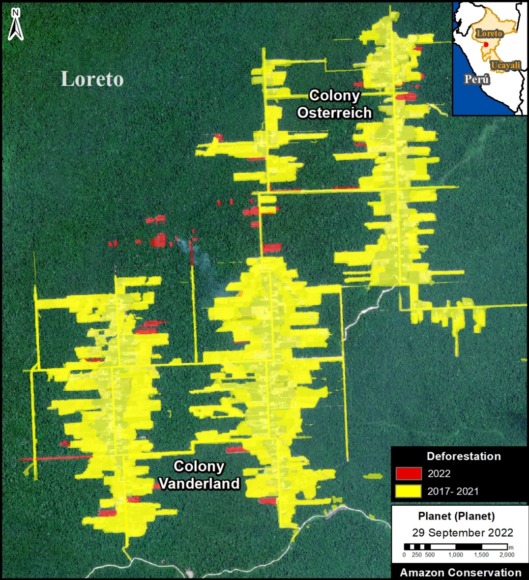

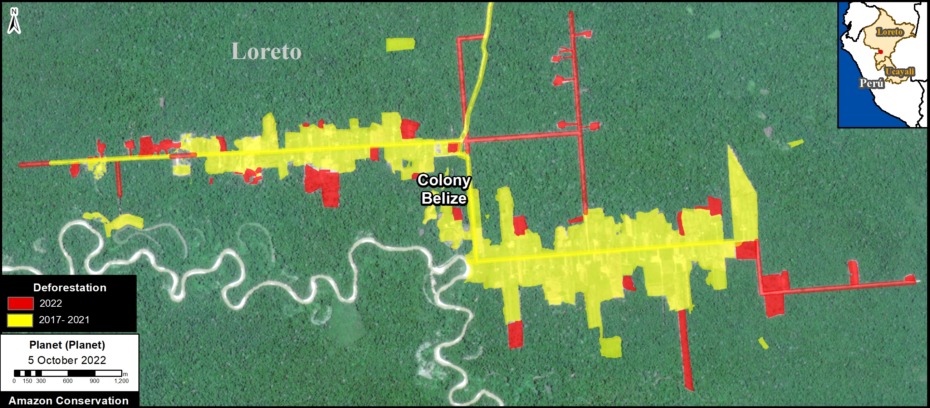

Vanderland, Osterreich & Providencia Colonies

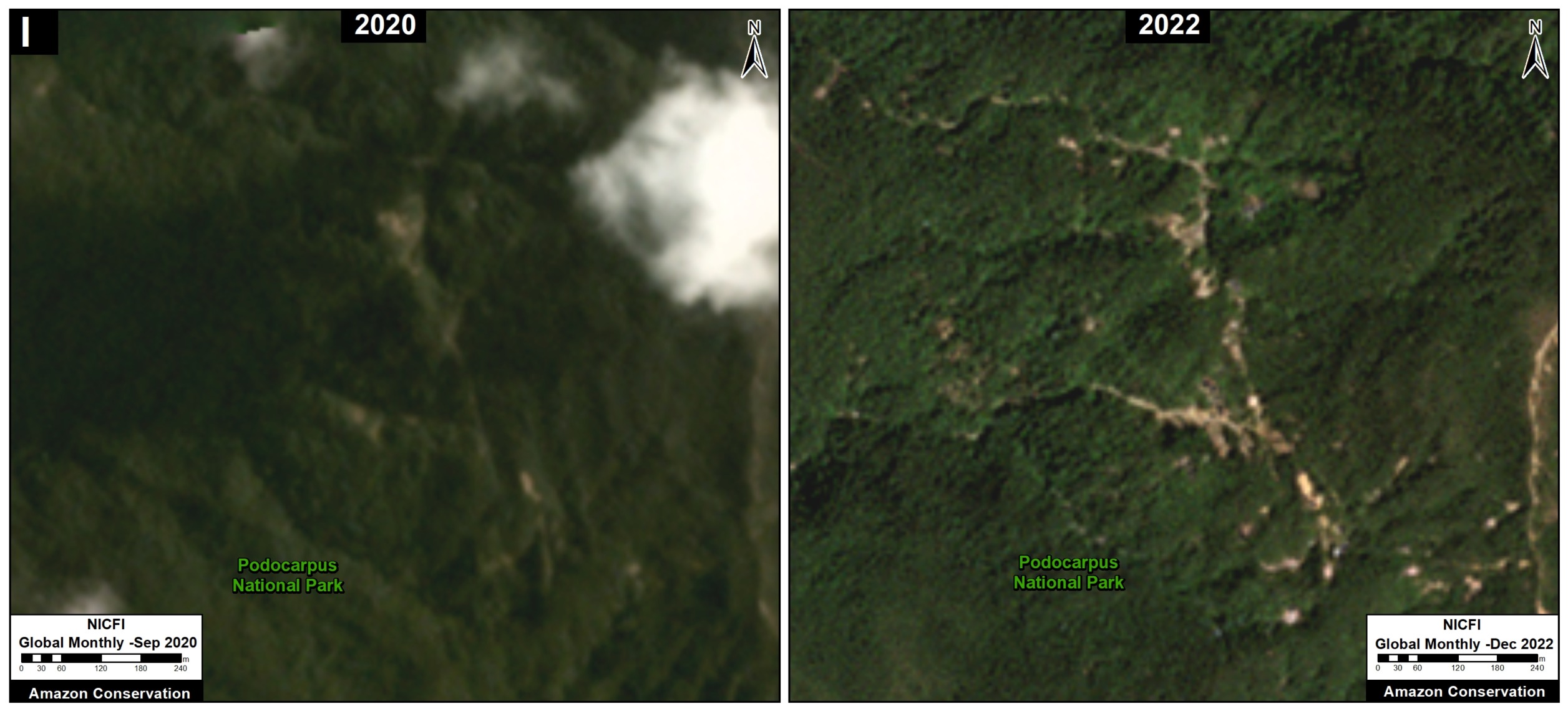

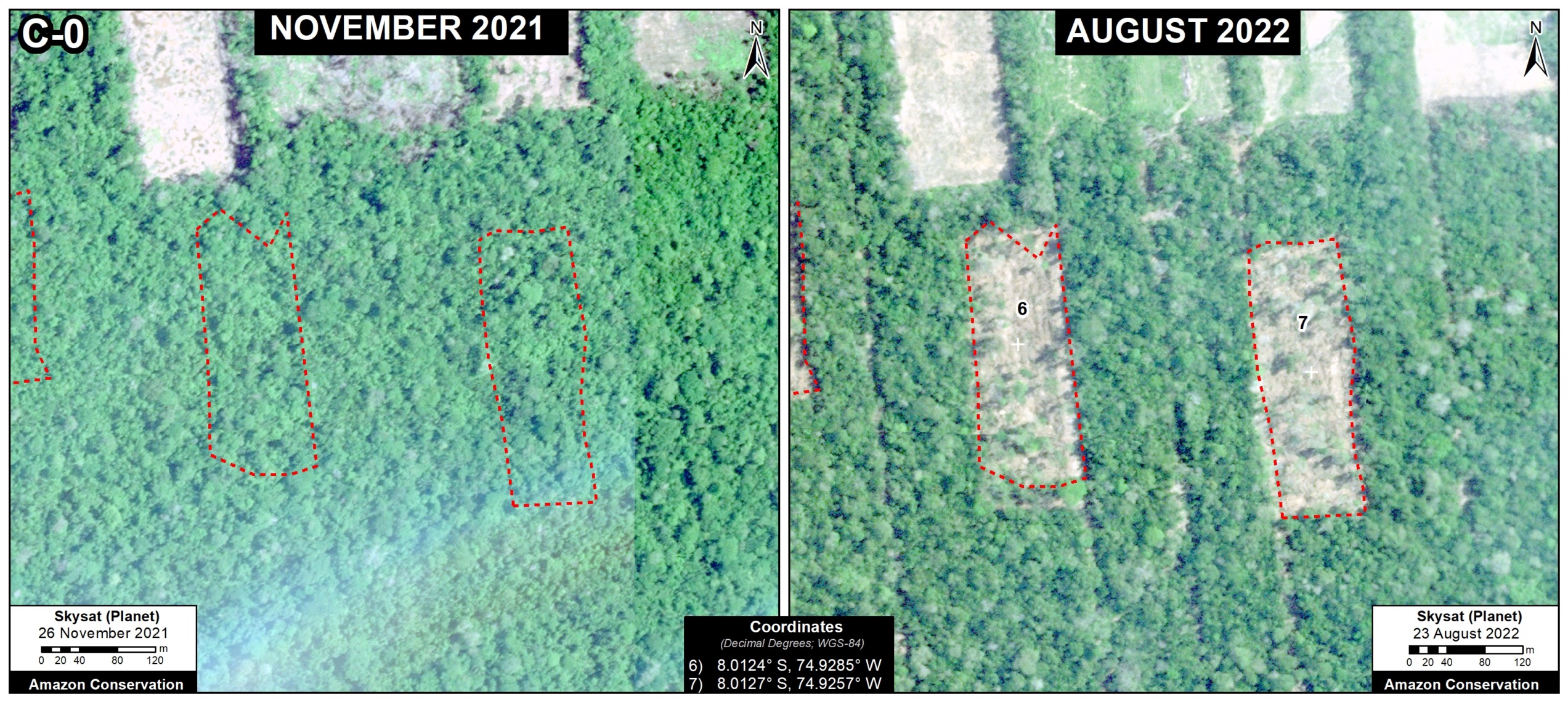

These three colonies are located near the town of Tierra Blanca, in the Loreto region.

In total, we have documented the deforestation of 3,881 hectares since 2017, with 32.5% occurring in the most recent 2022 – 2023 period (see image below).

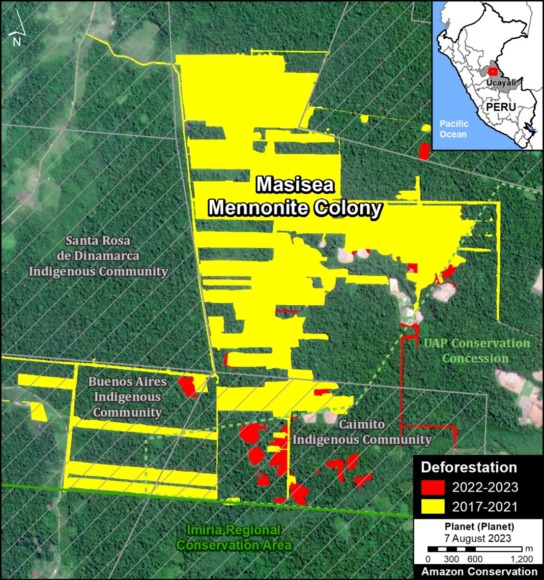

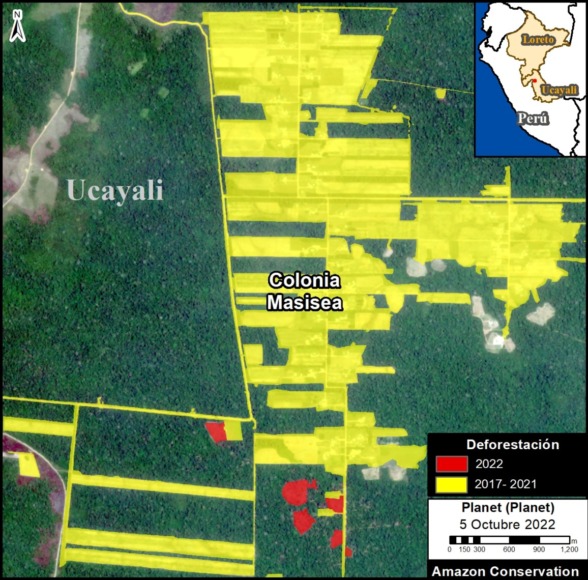

Masisea Colony

This colony, located in the Ucayali region, was the first to be established in Peru and was occupied with colonists arriving from Bolivia.

In total, we document the deforestation of 929 hectares in the Masisea colony since 2017 (see image below). Deforestation was highest between 2017 and 2019, and just 6% occurred in the most recent 2022 – 2023 time period.

Legal Summary

The Specialized Environmental Prosecutor’s Office, known as FEMA (Fiscalia Especializada en Materia Ambiental), is conducting investigations against the Mennonite colonies in each of the three areas:

- In Masisea, which is the most advanced case, the accusation is for illegal trafficking of timber forest products, crimes against forests in an aggravated form, alteration of the environment or landscape, and crimes against the forests of an indigenous community (tráfico ilegal de productos forestales maderables, delitos contra los bosques en forma agravada y alteración del ambiente o paisaje, y delitos contra los bosques de una comunidad nativa).

j - In the colonies of Tierra Blanca, the accusations include crimes against forests or wooded areas and misuse of agricultural lands (delitos contra los bosques o formaciones boscosas y por utilización indebida de tierras agrícolas).

j - In Chipiar, officially known as the Christian Agricultural Mennonite Colony Gnadenhoff Reinlaender Benboya, the accusation is crime against forests or forest formations in aggravated form (delito contra los bosques o formaciones boscosas en forma agravada).

The Public Prosecutor of the Ministry of the Environment has indicated that all deforestation has occurred without the proper authorization from the relevant state agencies. The regional governments of Ucayali and Loreto have confirmed this assertion, stating that there is no authorization for land use change.

In addition, the National Forest Service (SERFOR) has received five complaints against the Mennonite colonies in the three sectors (two for Masisea, two for Tierra Blanca, and one for Chipiar). These complaints have been forwarded to the respective regional governments and to FEMA in Loreto and Ucayali.

In general, the Mennonites have followed the same pattern in each area: First, there is an irregular purchase of land. Then, they proceed with land use change and deforestation without proper authorization.

In October 2022, the Ucayali Transitory Preparatory Investigation Court for Environmental Crimes (Juzgado de Investigación Preparatoria Transitorio de Delitos Ambientales de Ucayali) ruled in favor of the request of the Attorney General of the Ministry of the Environment, in relation to deforestation in the Chipiar colony. In July 2023, the Second Criminal Appeals Chamber of the Superior Court of Justice of Ucayali (Segunda Sala Penal de Apelaciones de la Corte Superior de Justicia de Ucayali) ratified the immediate suspension of predatory activities of clearing and logging by the colony. According to the judicial order, the members of this Mennonite colony will not be able to use vehicles, machinery or instruments that cause deforestation.

Sources:

Mongabay Latam

https://es.mongabay.com/2022/10/tiruntan-perdio-sus-bosques-tras-la-llegada-de-menonitas-en-peru/

https://es.mongabay.com/2020/11/menonitas-peru-deforestacion-loreto/

https://es.mongabay.com/2021/04/menonitas-peru-historia-entrega-bosques-masisea/

Ojo Publico

https://ojo-publico.com/ambiente/territorio-amazonas/las-visitas-al-congreso-detras-del-proyecto-que-amenaza-los-bosques

Convoca

Actualidad Ambiental

https://www.actualidadambiental.pe/ordena-suspender-depredacion-de-bosques-a-colonia-menonita/

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues at USAID in Peru and Conservación Amazónica-ACCA for helpful input and comments on this report, and R. McMullen for translation.

This report was prepared with the technical support of USAID through the Prevent Project. Prevent (Proyecto Prevenir in Spanish) works with the Government of Peru, civil society, and the private sector to prevent and combat environmental crimes for the conservation of the Peruvian Amazon, particularly in the regions of Loreto, Madre de Dios, and Ucayali.

Disclaimer: This publication is made possible by the generous support of the American people through USAID. The contents are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2023) Mennonite Colonies Continue Major Deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 188.