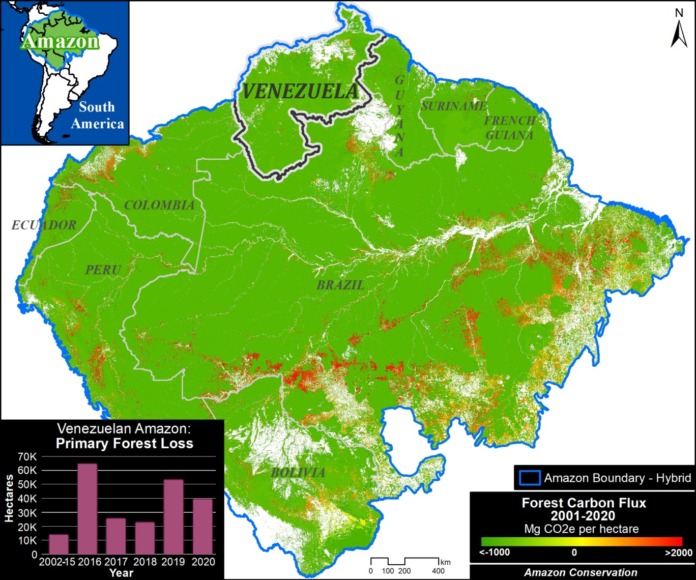

We present here the first report of a series focused on the Venezuelan Amazon, which covers over 47 million hectares of the northern section of the Amazon biome (above western Brazil).

As the Amazon Base Map indicates, Venezuela is a key part to the remaining core Amazon that is still functioning as a critical carbon sink, making it an important piece to long-term conservation strategies.

However, deforestation has been increasing in recent years (see graph in Base Map), indicating escalating threats.

Specifically, there is a clear trend of increasing primary forest loss since 2015, including a recent spike in 2019.

We estimate the loss of over 140,000 hectares (345,000 acres) over the past four years, accounting for 1.6% of the total loss across the Amazon during that time period.

Below, we investigate the major hotspots and drivers of deforestation currently in the Venezuelan Amazon.

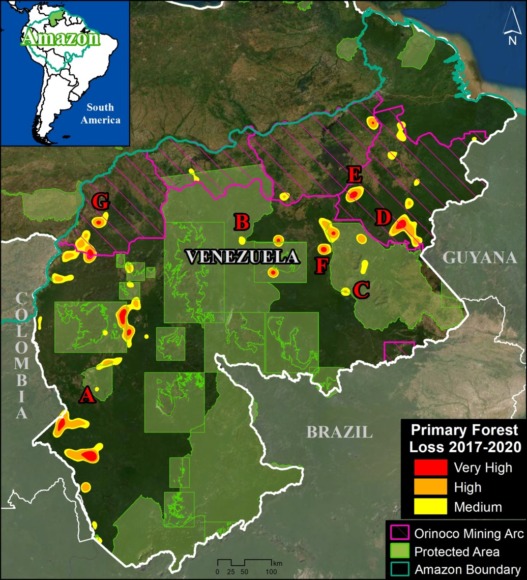

The Venezuela base map shows the major hotspots of primary forest loss across the Venezuelan Amazon over the past four years (2017-2020).

Note that most hotspots are within the Orinoco Mining Arc, a large area over 11 million hectares created by a controversial presidential decree in 2016 designed to promote mining (SOSOrinoco 2021), as well as within and around the extensive network of protected areas.

These protected areas cover 43% (20 million hectares) of the Venezuelan Amazon and accounted for around 30% of total forest loss. The most impacted areas in recent years are Caura, Canaima, and Yapacana National Parks (over 22,000 hectares combined).

We zoomed in on these hotspots and found that mining, fires, and agriculture (including cattle pasture) are the three primary deforestation drivers across the Venezuelan Amazon. There may be complex interactions between these drivers, such as mining centers leading to fires and agricultural expansion to support the new mining population.

It is worth noting that Venezuela joins Peru, Brazil, and Suriname as countries where mining is now documented to be actively driving major deforestation of primary forest.

We also note that, as in the rest of the Amazon, virtually all fires are caused by humans (that is, not natural events) and most are likely linked to preparing land for agricultural activities. During drier periods, these fires may escape, causing larger forest fires.

Below, we illustrate these drivers in a series of high-resolution (3 meters) and very high-resolution (0.5 meters) images.

High-resolution Zooms

Mining

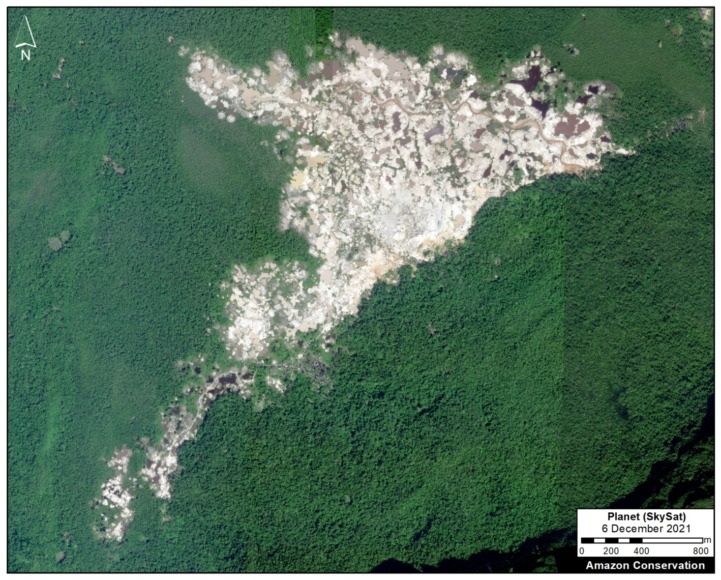

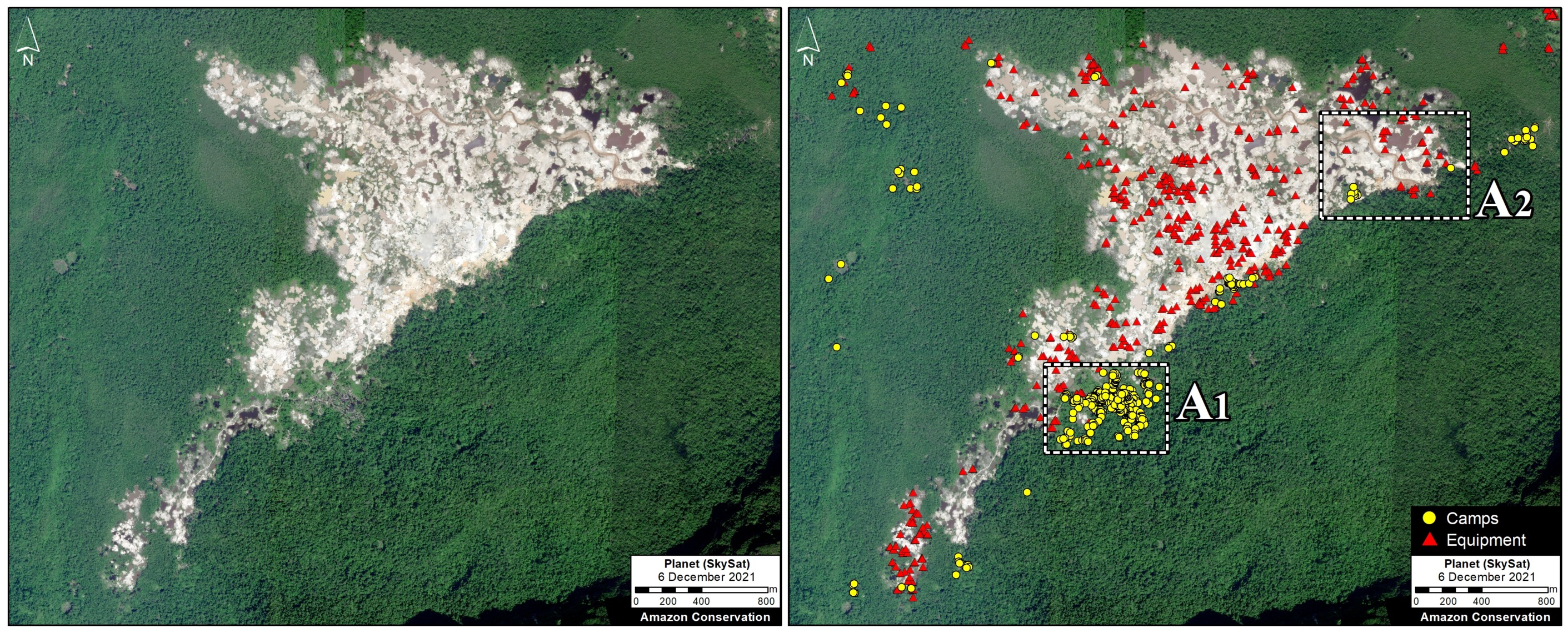

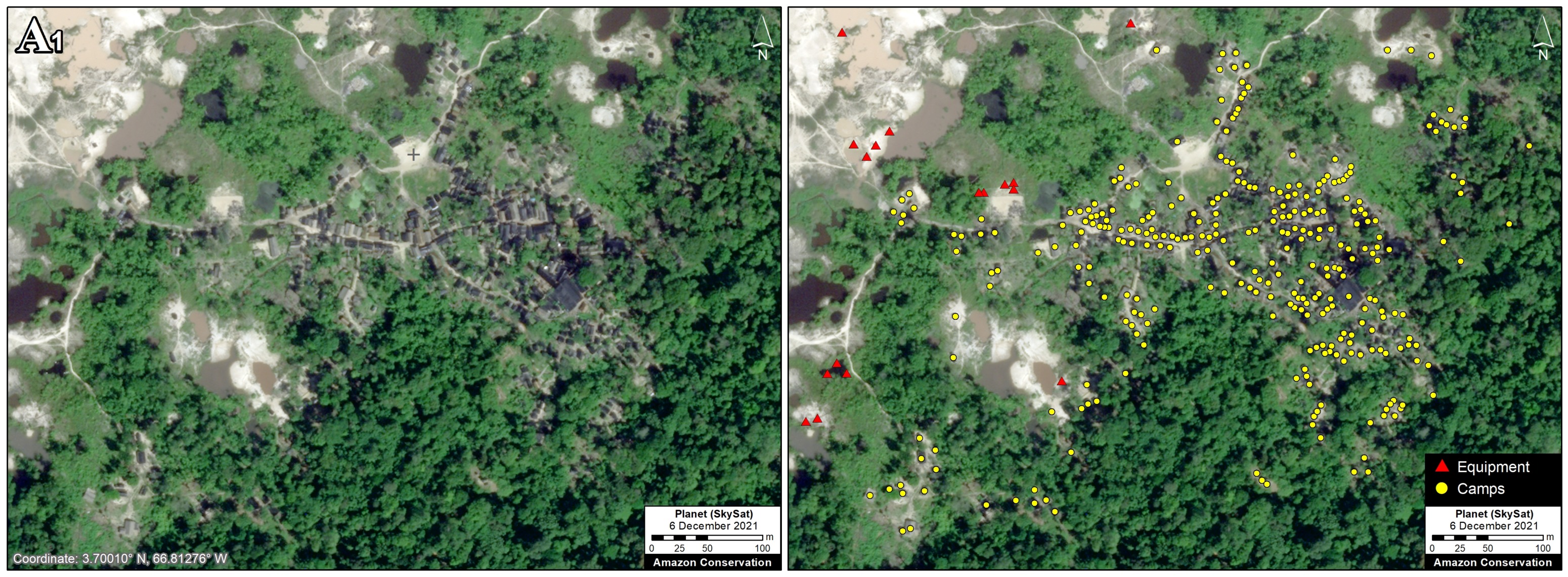

Zoom A. Yapacana National Park

Yapacana National Park, which is a unique mosaic of natural savannas and forest, is currently experiencing deforestation impacts from active mining operations. We show two examples of recent mining in the Cerro Yapacana mining sector, featuring very-high resolution imagery from late 2021 (see Zooms A1 and A2). These two areas have lost over 550 hectares since the early 2000s.

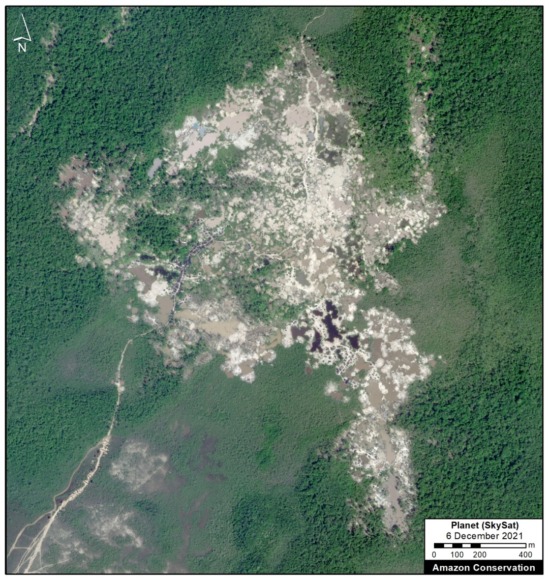

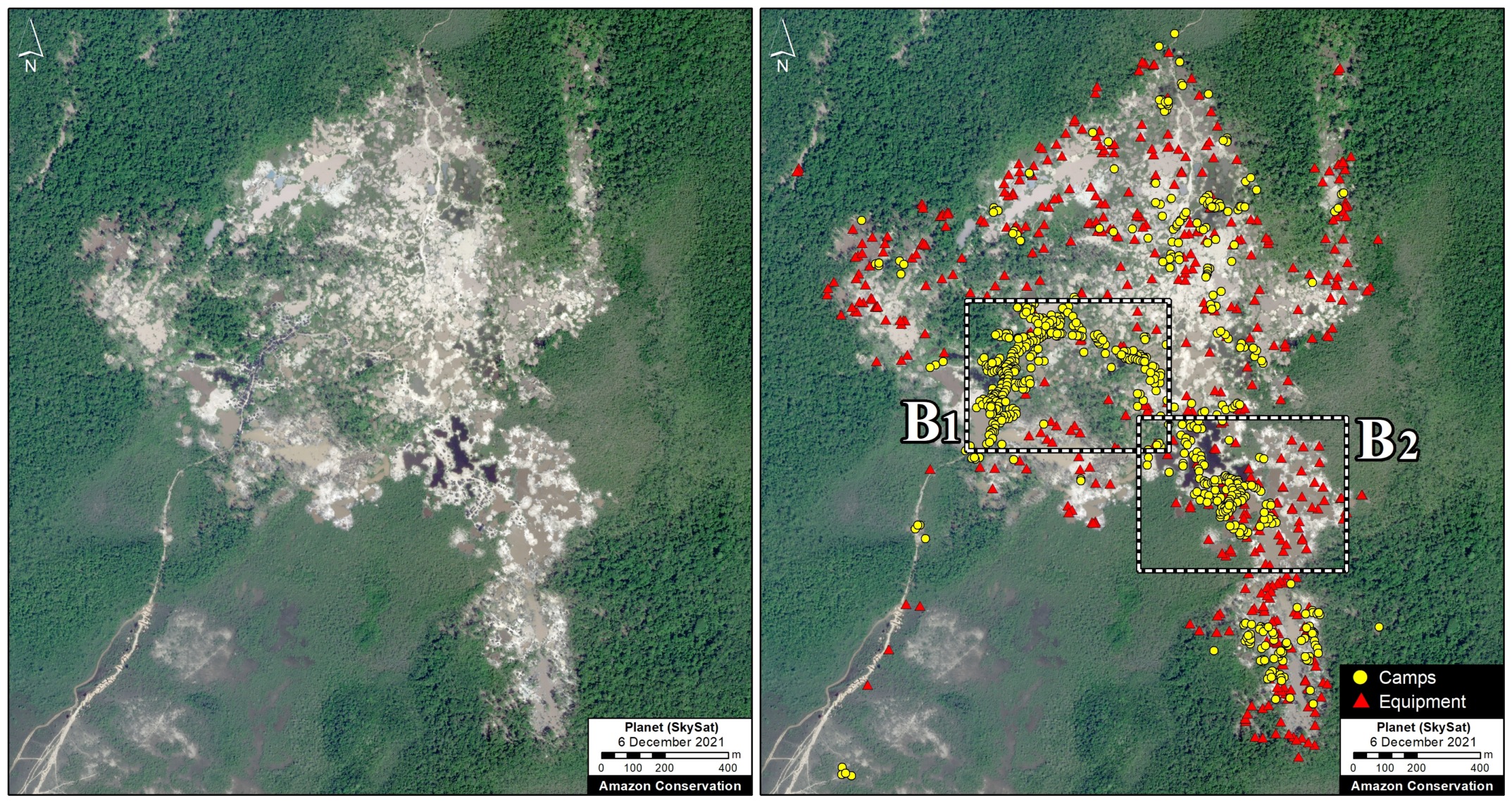

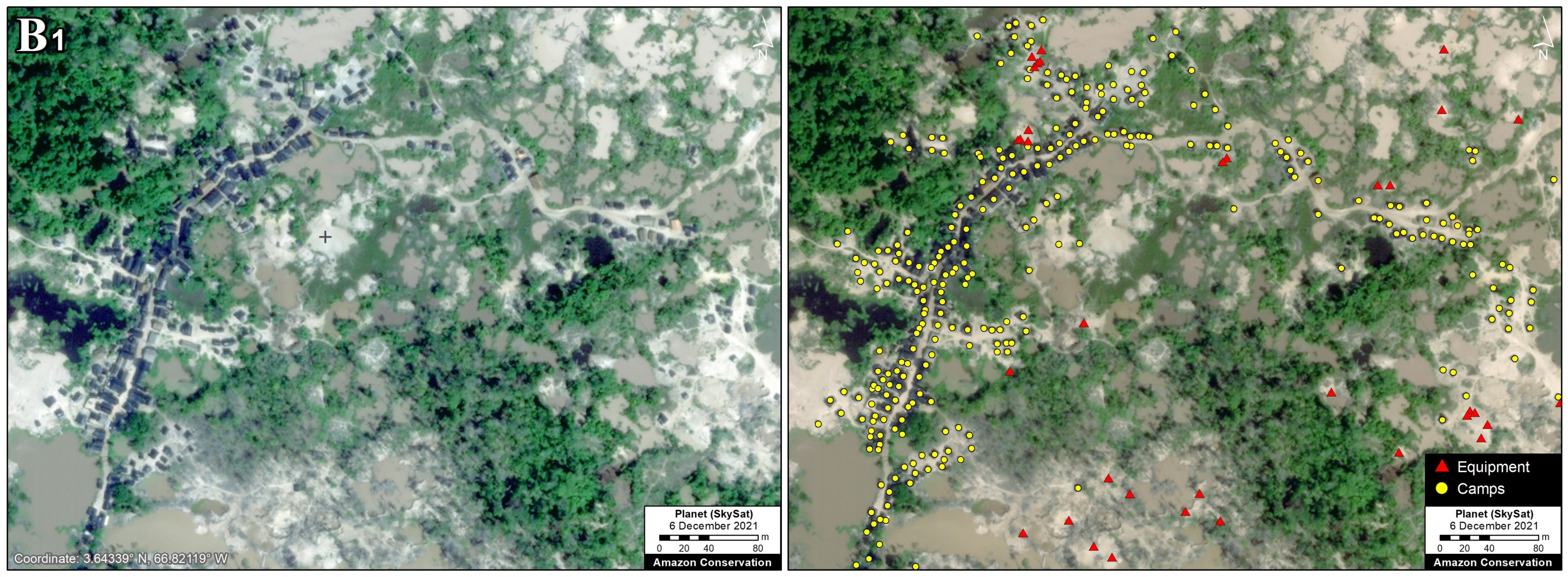

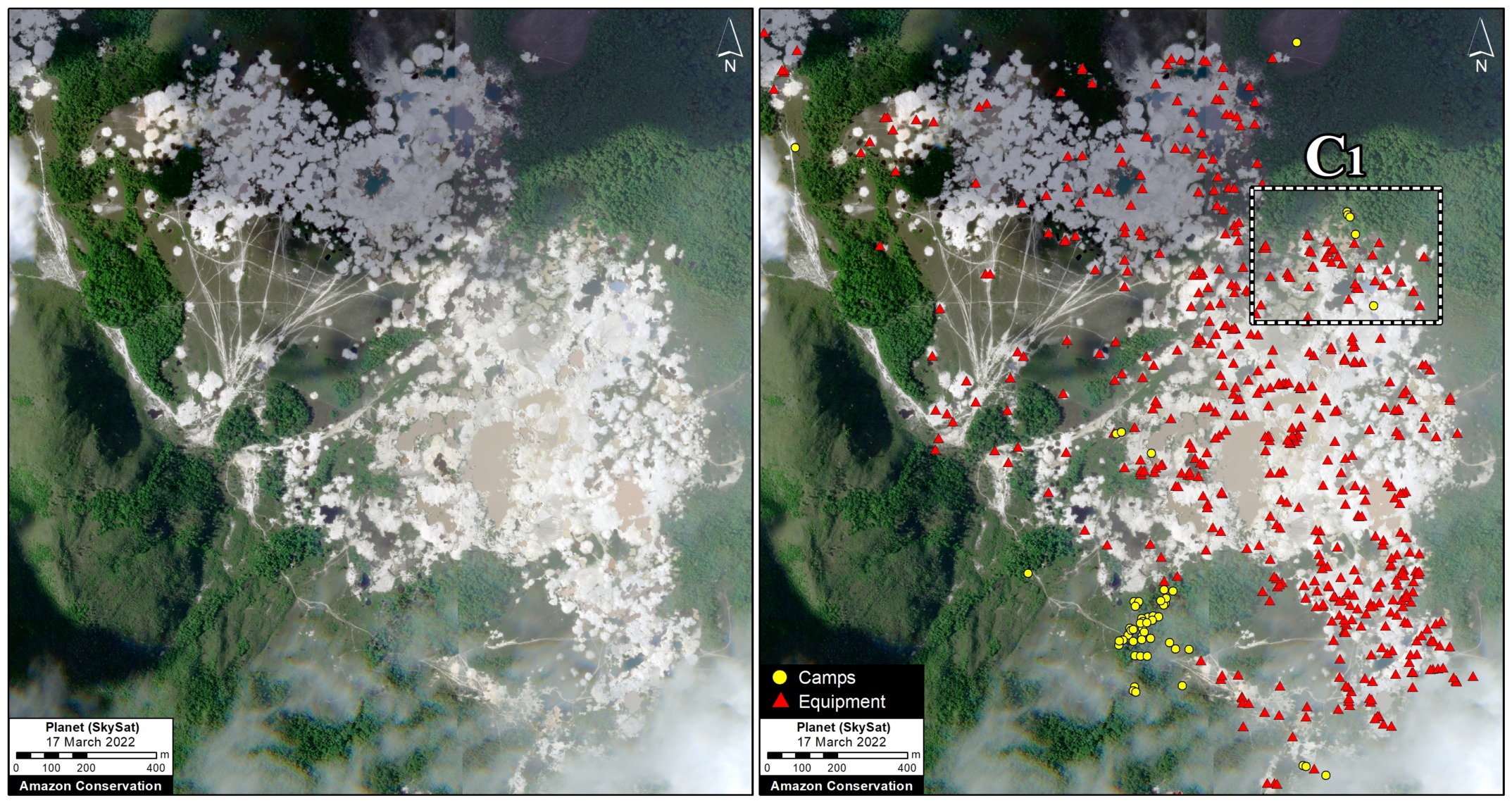

Zoom B. Caura National Park

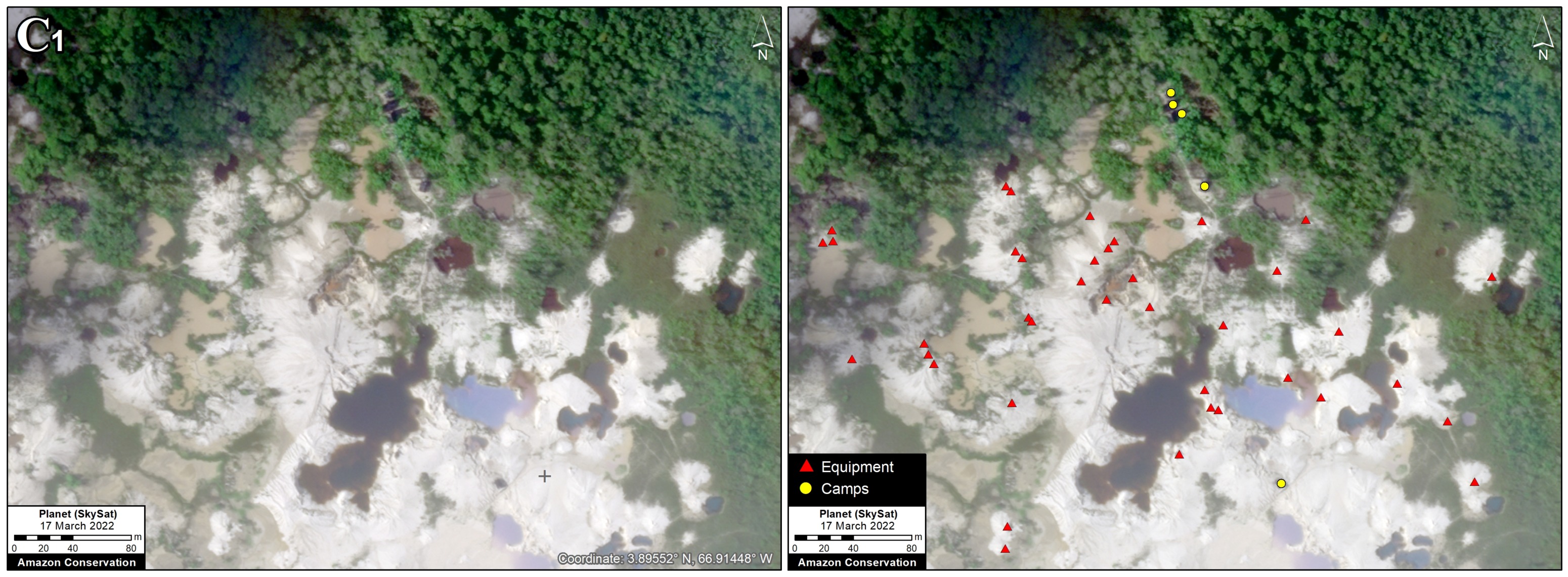

Caura National Park is also experiencing active mining activity. Below are two examples of recent mining activity, featuring very-high resolution imagery from early 2022 (see Zooms B1 and B2).

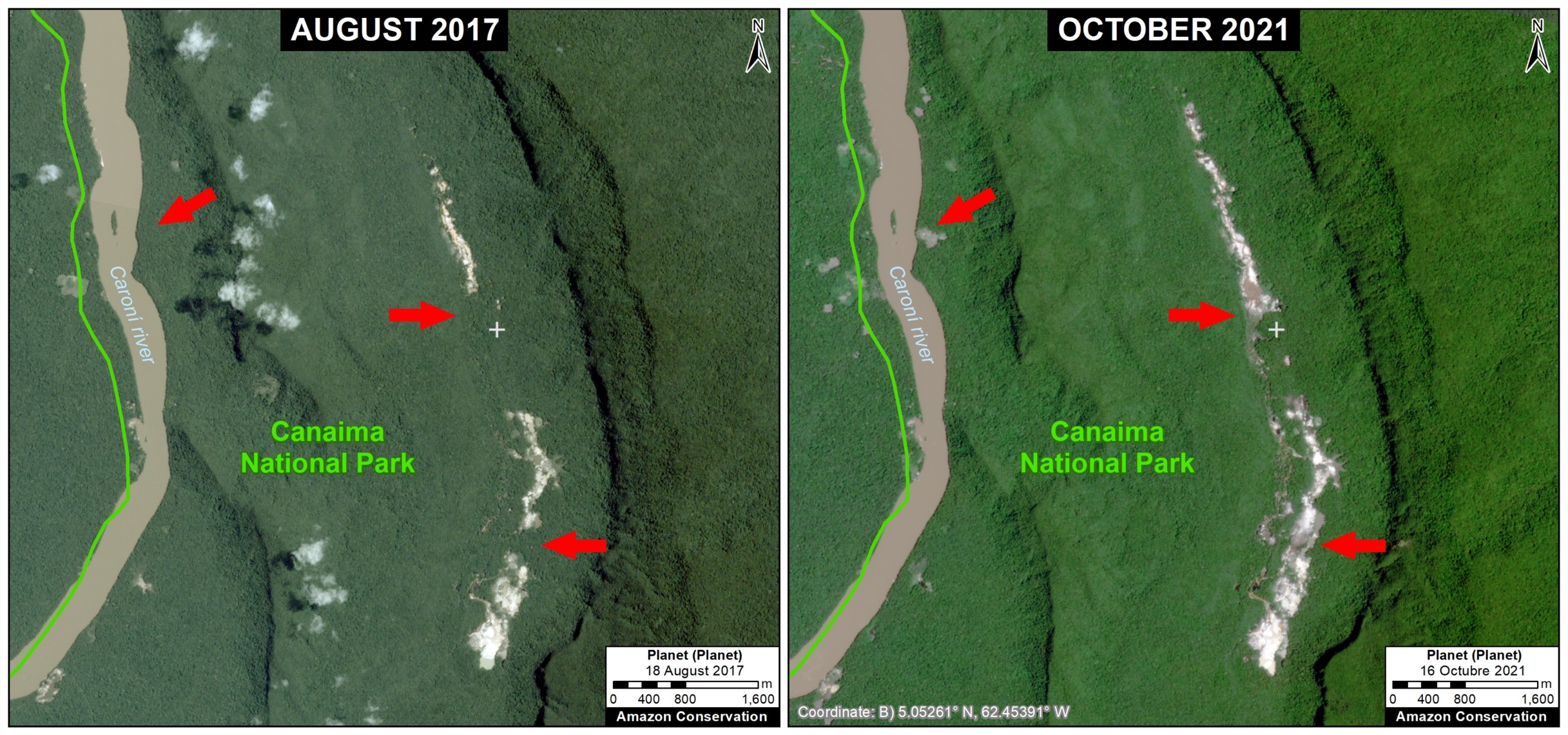

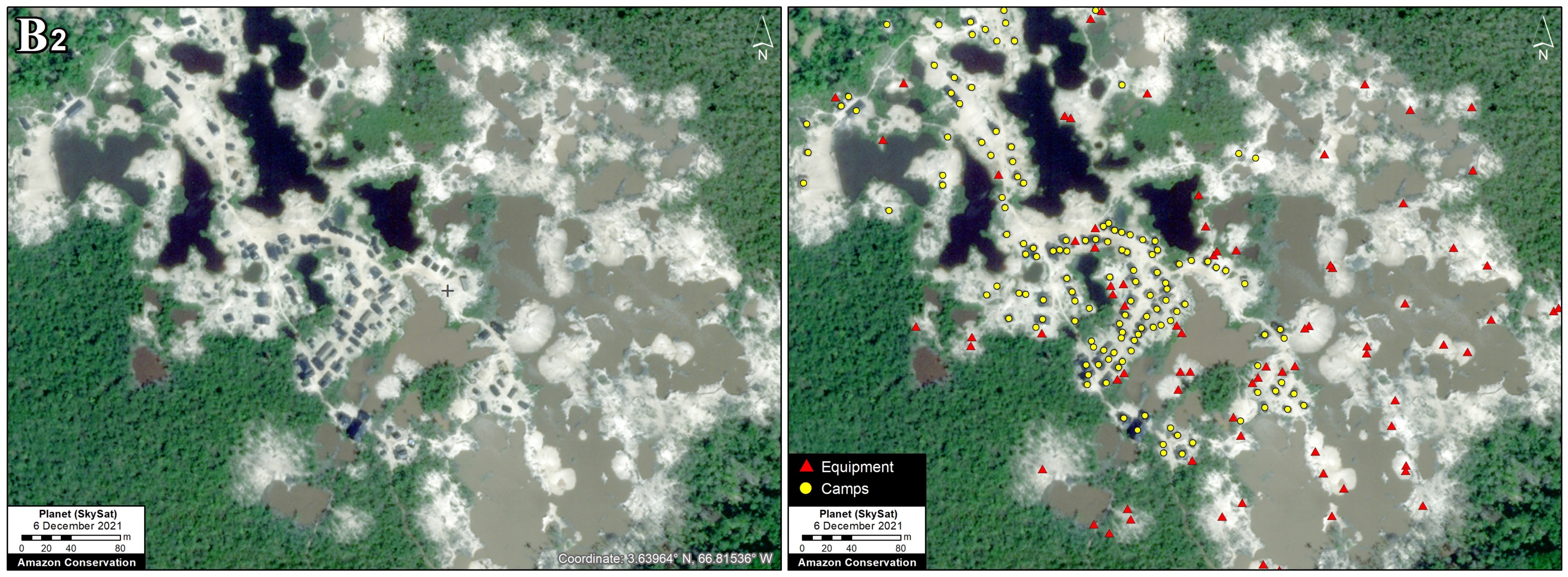

Zoom C. Canaima National Park

The following image shows the recent expansion of mining deforestation in Canaima National Park between 2017 (left panel) and 2020 (right panel).

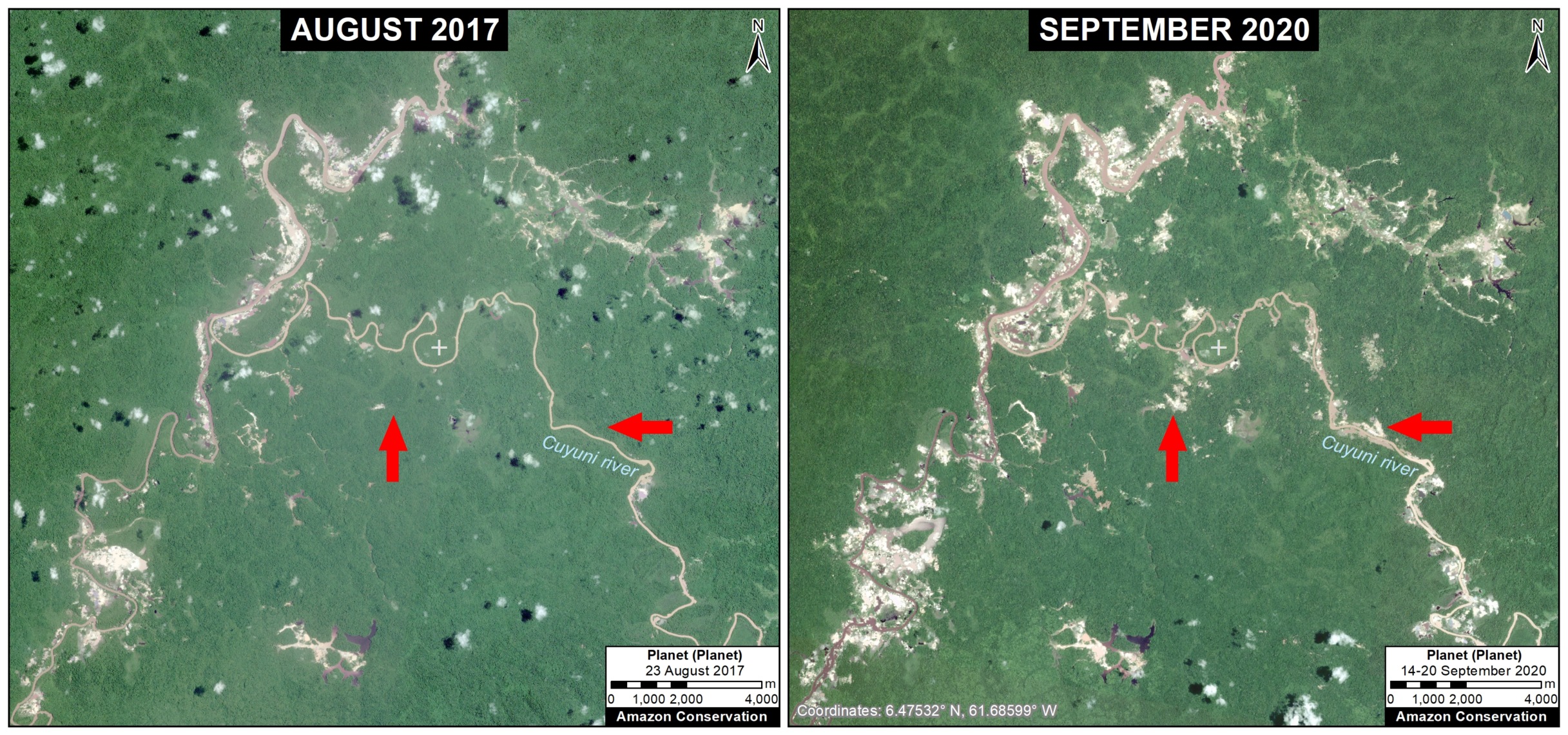

Zoom D: Orinoco Mining Arc

To the north of these protected areas, there is both industrial and river-based mining deforestation in the Orinoco Mining Arc. Zoom D shows an example of major river-based mining deforestation (over 1,800 hectares) between 2017 and 2020, plus a very-high resolution imagery from late 2021.

Agriculture

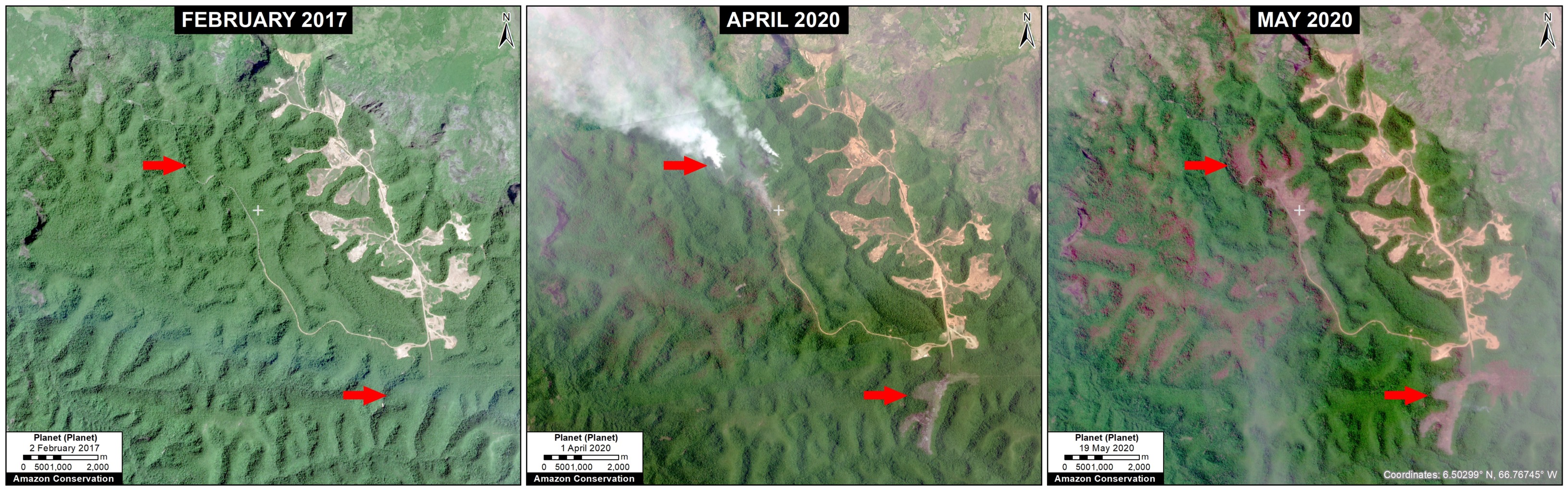

Zoom E shown an example of agricultural expansion (likely cattle ranching) in the northeastern section of the Orinoco Mining Arc. We estimate the forest loss shown in the panels between 2017 and 2020 is over 400 hectares.

Fire

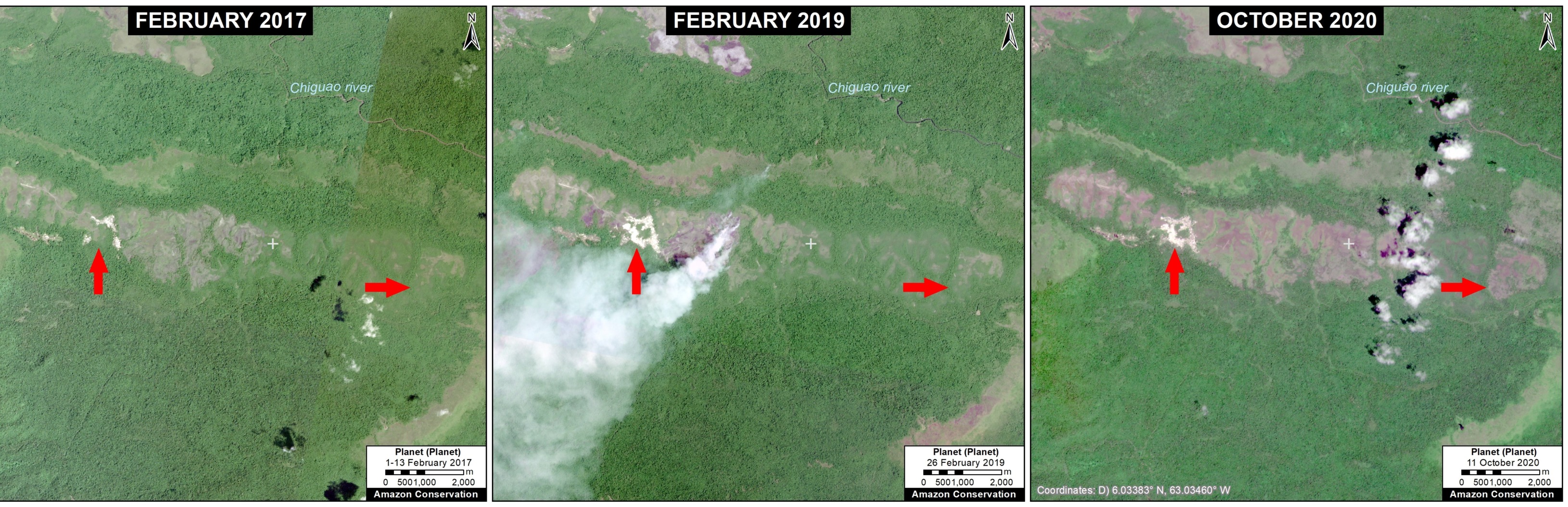

Finally, Zooms F and G show recent examples of major fires impacts. Zoom F is an area that experienced major fires in 2019 within and around Canaima National Park. We estimate the forest loss shown in the panels between 2017 and 2020 is 1,175 hectares.

Zoom G is an area that experienced major fires in 2020 in the near mining sites in the western section of the Orinoco Mining Arc. We estimate the forest loss shown in the panels between 2017 and 2020 is 1,128 hectares.

Methodology

For a study area with maximum inclusion, for the Venezuelan Amazon we used the wider biogeographic boundary (as defined by RAISG) rather than the strict Amazon watershed boundary (which actually only includes a small portion of Venezuela).

We obtained data for the Orinoco Mining Arc (Arco Minero del Orinoco) and protected areas from the organization SOSOrinoco. The latter dataset contains Areas Under Special Administration Regime (Áreas Bajo Régimen de Administración Especial – ABRAE), which meet the IUCN international definition of protected areas: national parks, natural monuments, wildlife refuges, reserves and sanctuaries.

We used “primary forest loss” data as our proxy for 2002-2020 annual deforestation. This 30-meter resolution (based on Landsat) data is produced by the University of Maryland and presented by Global Forest Watch. Note that it includes forest loss from fires and natural causes. 2021 early warning alert data is also from University of Maryland.

To identify primary forest loss hotspots, we conducted a kernel density estimate. This type of analysis calculates the magnitude per unit area of a particular phenomenon, in this case forest cover loss. We conducted this analysis using the Kernel Density tool from Spatial Analyst Tool Box of ArcGIS.

Finally, we investigated the major hotspots with both high resolution (3 meters) and very high resolution (0.5 meters) satellite imagery from the company Planet to identify causes (drivers).

References

SOSOrinoco. 2021. Deforestation & Changes in Vegetation & Land Use Cover within the so-called Orinoco Mining Arc between 2000-2020.

Acknowledgements

We thank the organization SOSOrinoco for important information and comments related to this report.

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2022) Deforestation Hotspots in the Venezuelan Amazon. MAAP: 155.