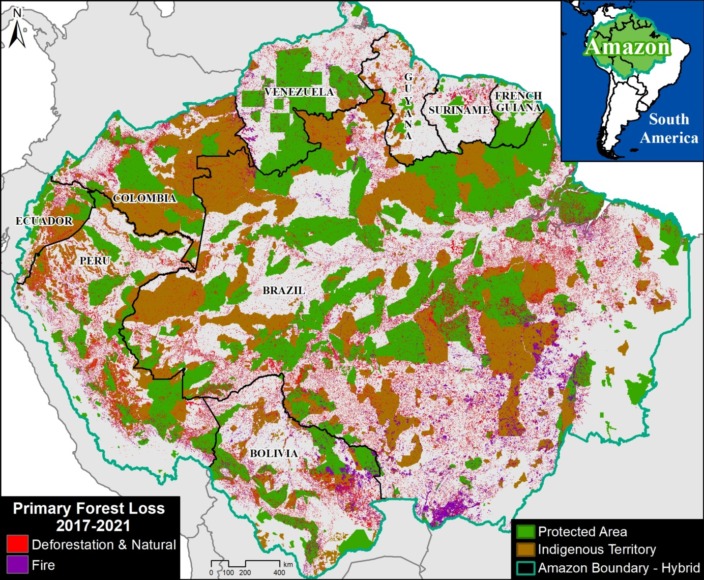

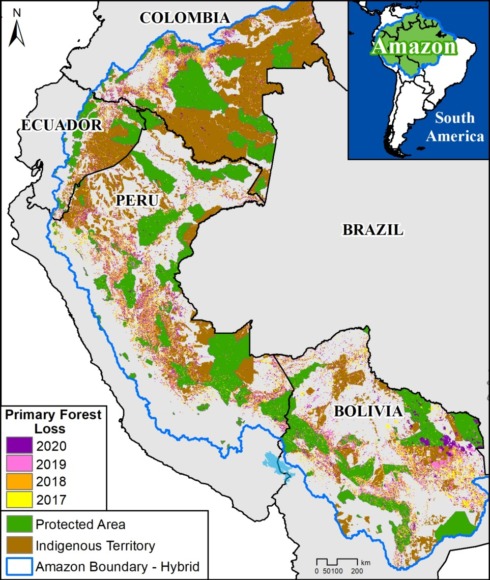

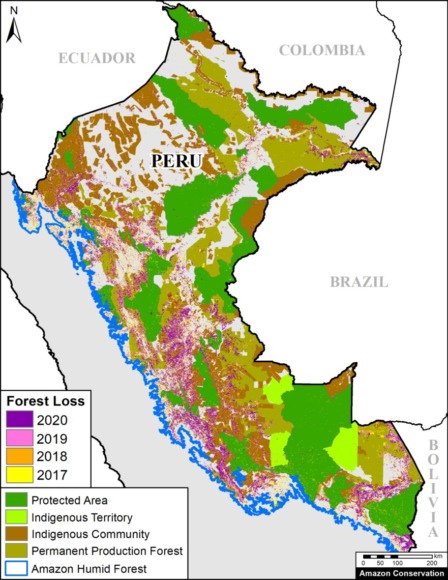

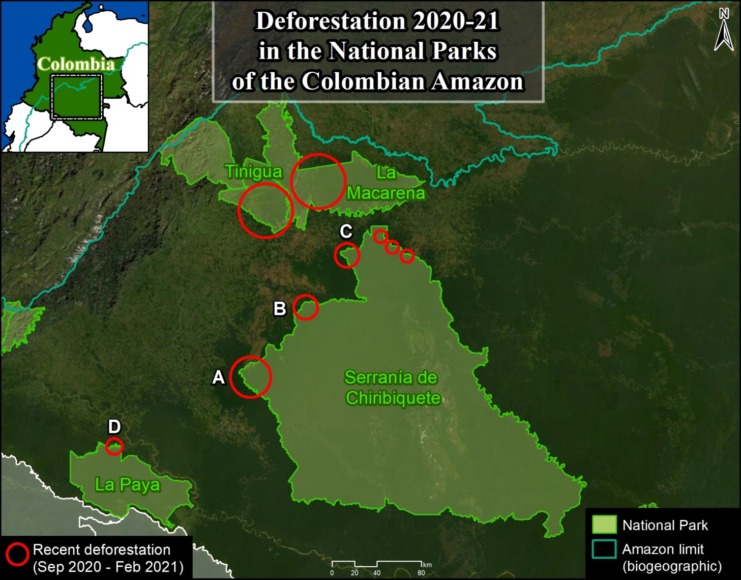

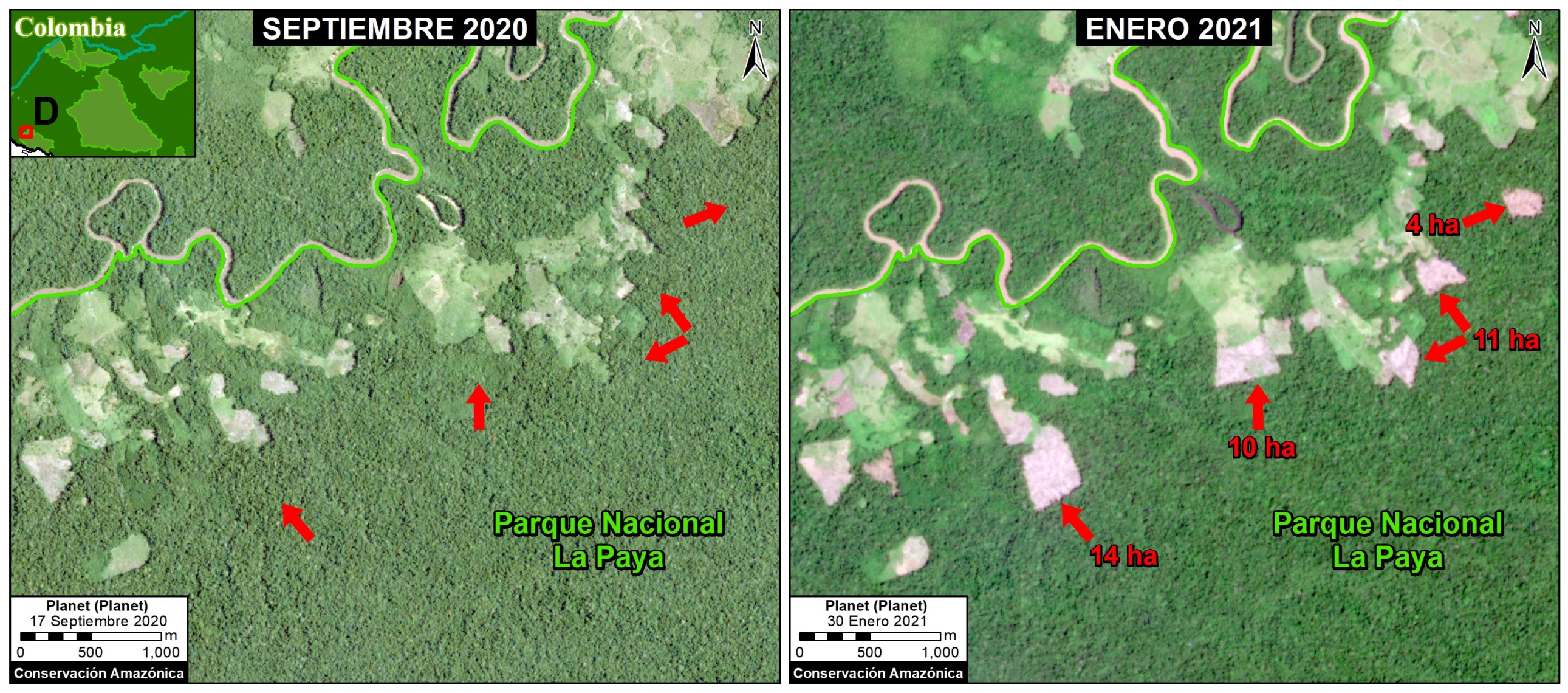

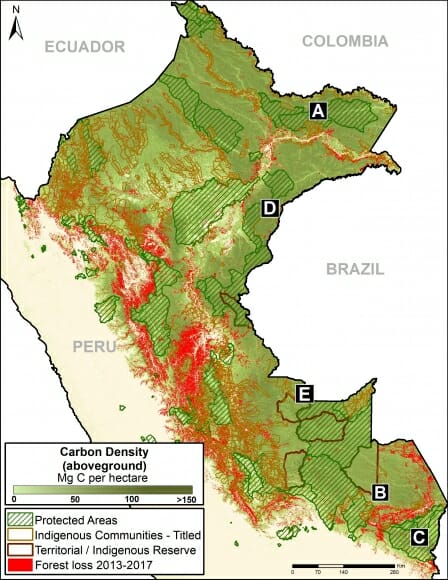

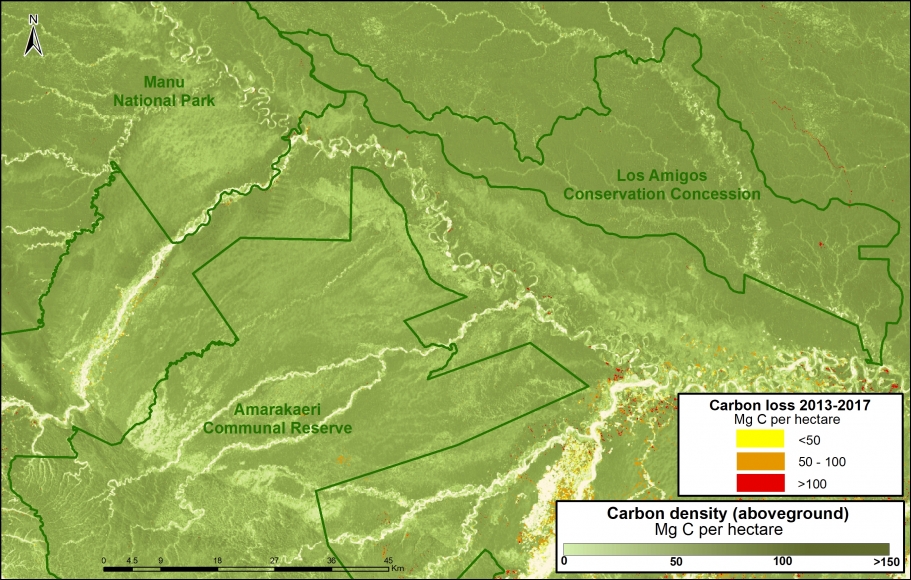

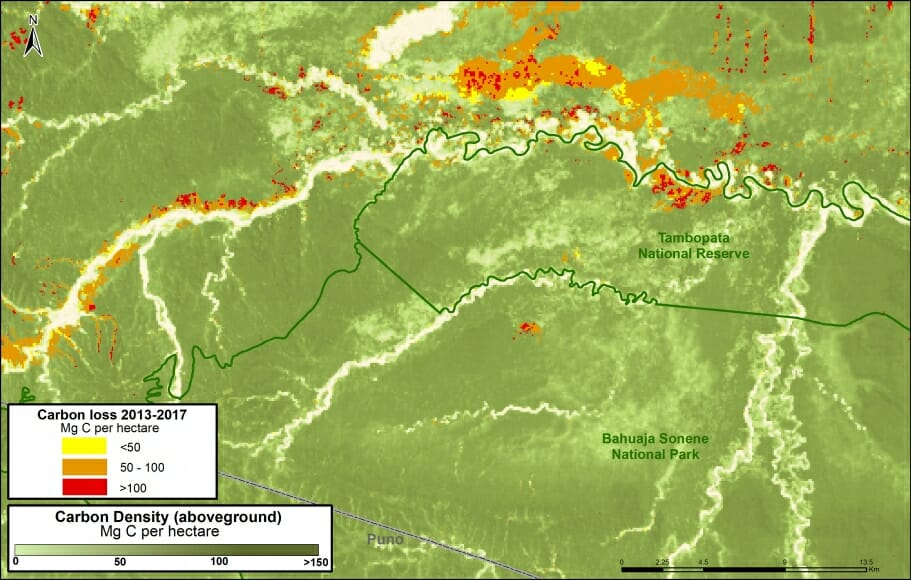

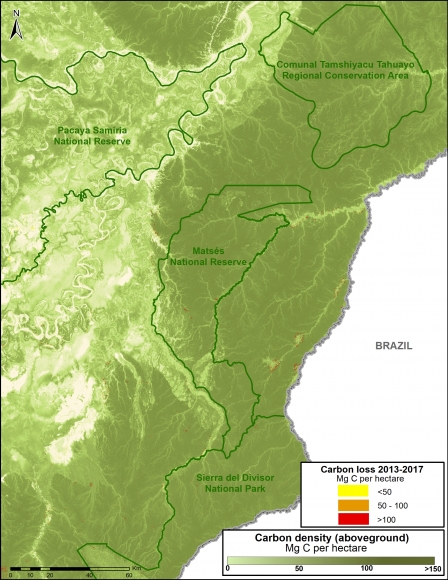

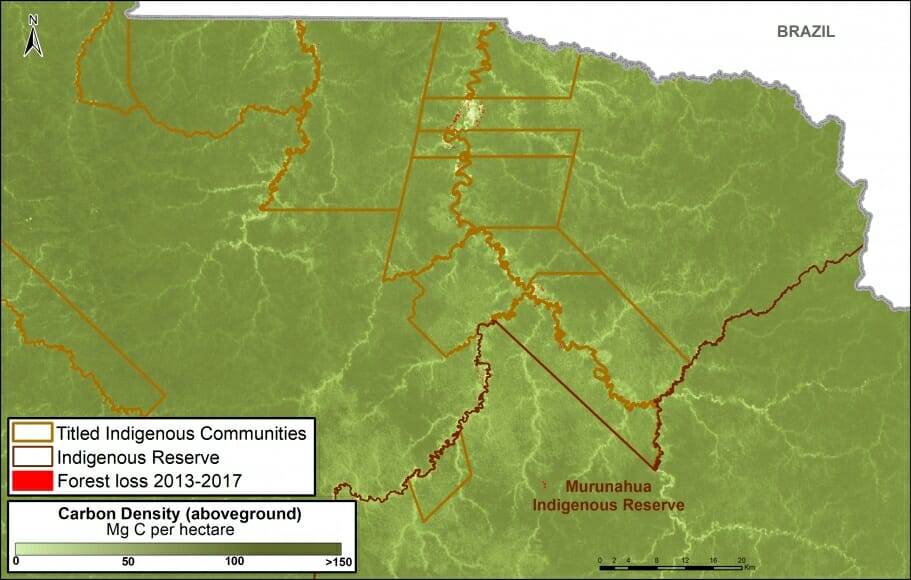

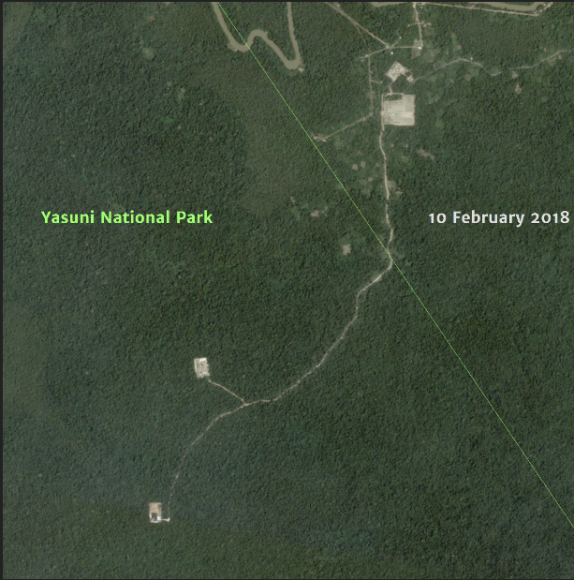

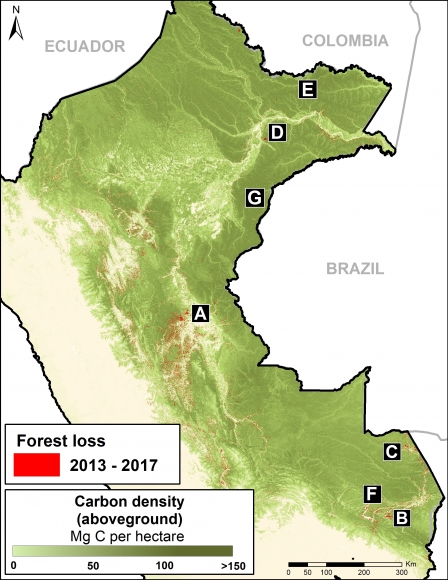

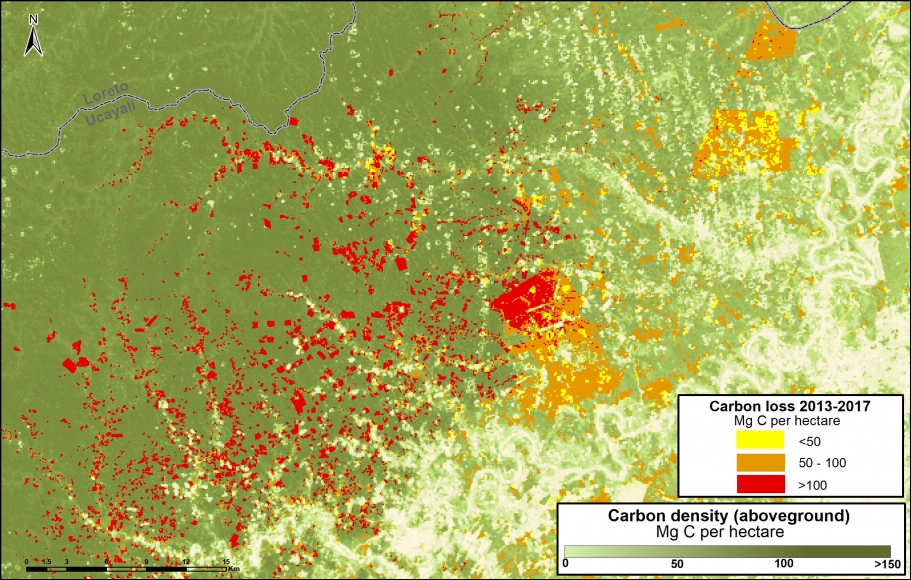

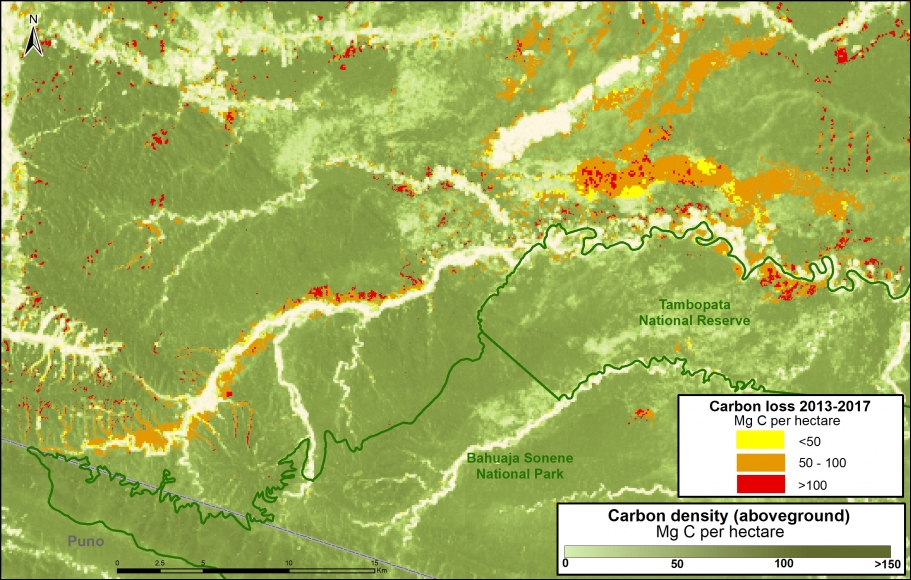

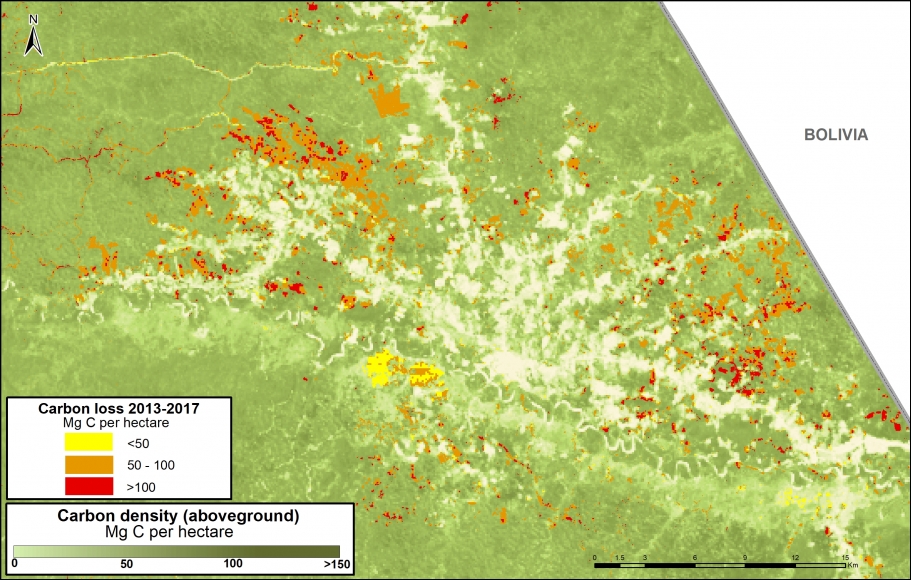

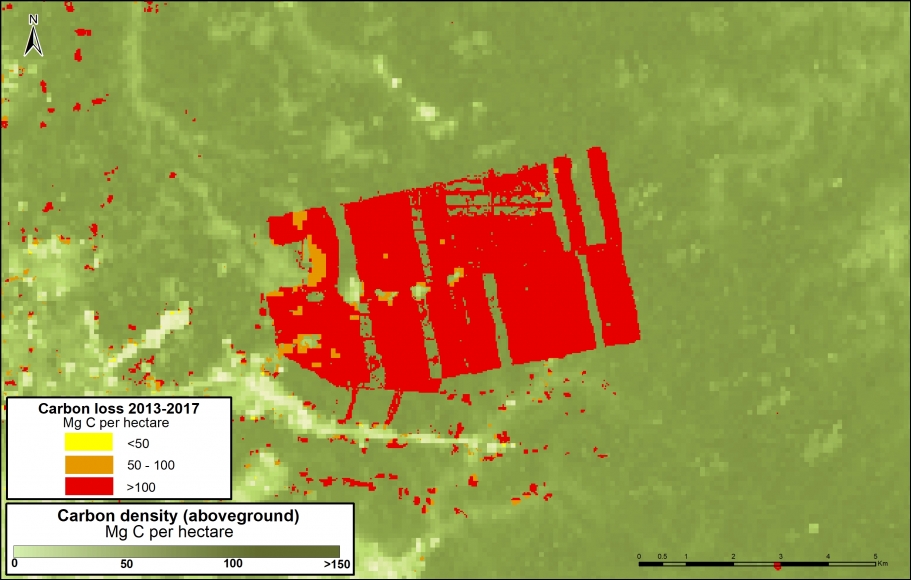

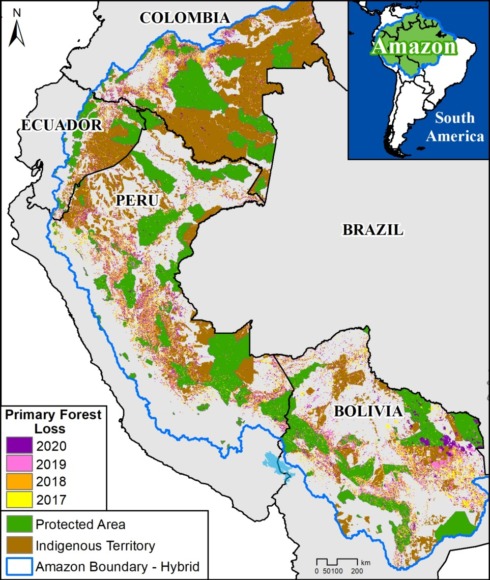

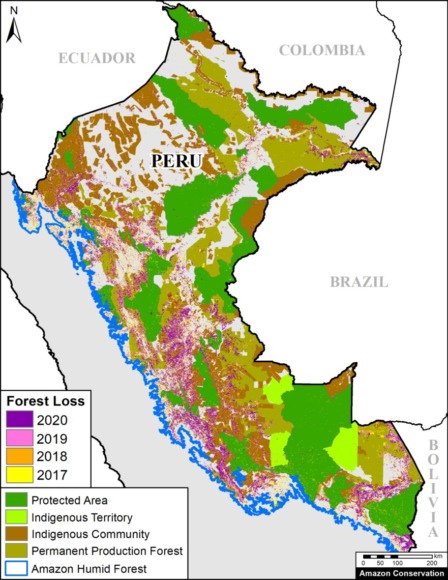

Base Map. Primary forest loss across the western Amazon, with magnified visualization of the data. Click to enlarge. See Methodology for data sources.

As deforestation continues to threaten primary forest across the Amazon, key land use designations are one of the best hopes for the long-term conservation of critical remaining intact forests.

Here, we evaluate the impact of two of the most important land use designations: protected areas and indigenous territories.

Our study area focused on the four mega-diverse countries of the western Amazon (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, & Peru), covering a vast area of over 229 million hectares (see Base Map).

We calculated primary forest loss over the past four years (2017-2020) across the western Amazon and analyzed the results across three major land use categories:

1) Protected Areas (national and state/department levels), which covered 43 million hectares as of 2020.

2) Indigenous Territories (official), which covered over 58 million hectares as of 2020.

3) Other (that is, all remaining areas outside protected areas and indigenous territories), which covered the remaining 127 million hectares as of 2020.

In addition, we took a deeper look at the Peruvian Amazon and also included long-term forestry lands.

In summary, we found that, averaged across all four years, protected areas had the lowest primary forest loss rate, closely followed by indigenous territories (see Figure 1). Outside of these critical areas, the primary forest loss rate was more than double.

Below, we describe the key results in greater detail, including a detailed look at each country.

Key Findings – Western Amazon

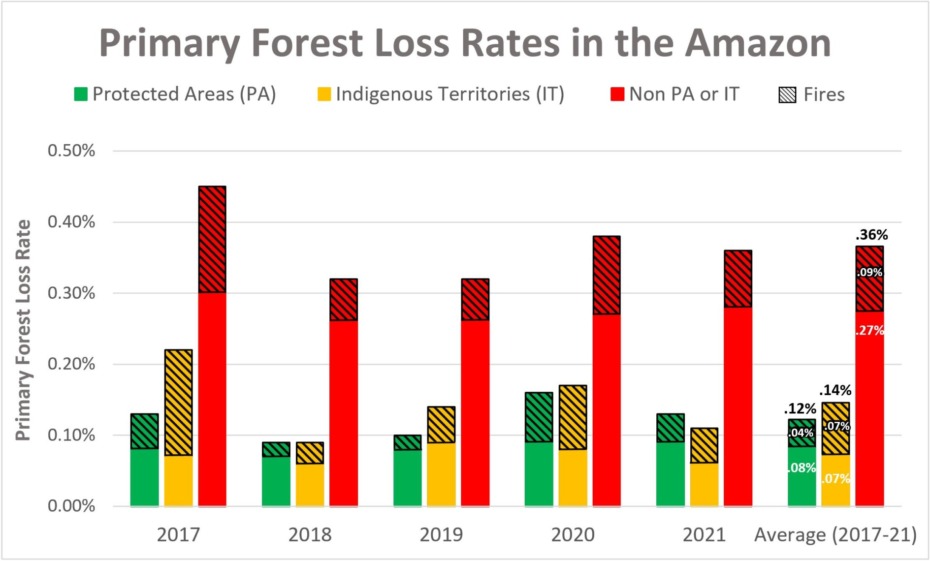

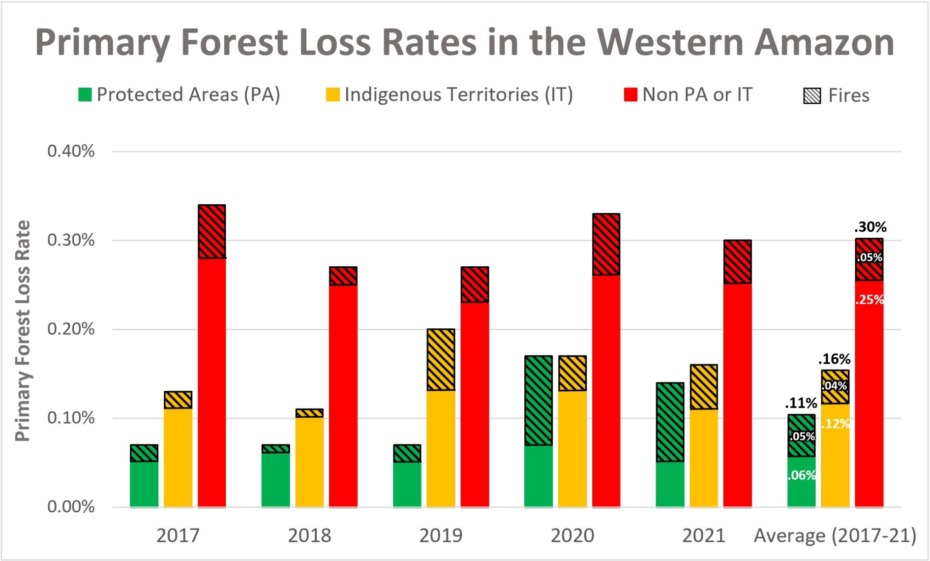

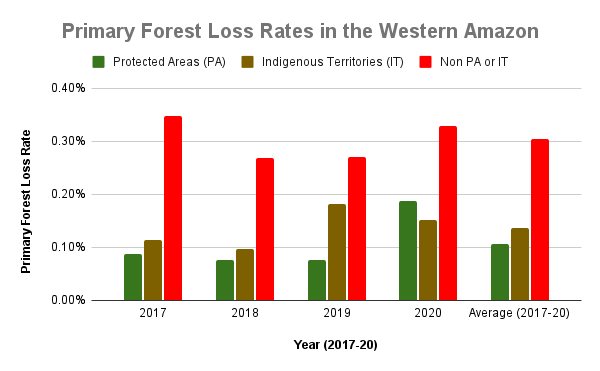

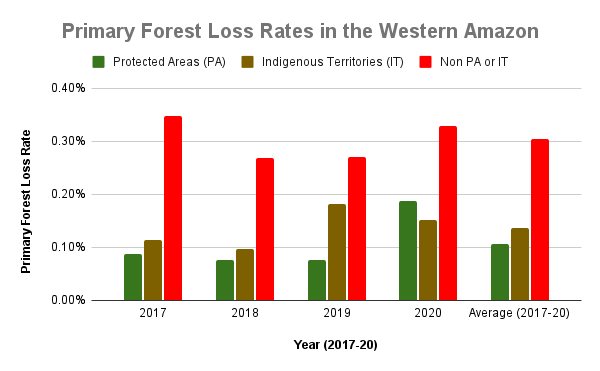

Figure 1. Primary forest loss rates in the western Amazon.

Overall, we documented the loss of over 2 million hectares of primary forests across the four countries of the western Amazon between 2017 and 2020. Of the four years, 2020 had the most forest loss (588,191 ha).

Of this total, 9% occurred in protected areas (179,000 ha) and 15% occurred in indigenous territories (320,000 ha), while the vast majority (76%) occurred outside key these land use designations (1.6 million ha).

To standardize these results for the varying area coverages, we calculated primary forest loss rates (loss/total area of each category). Figure 1 displays the combined results for these rates across all four countries.

From 2017-19, protected areas (green) had the lowest primary forest loss rates across the western Amazon (less than 0.10%).

Indigenous territories (brown) also had low primary forest loss rates from 2017-18 (less than 0.11%), but this rose in 2019 (0.18%) due to fires in Bolivia.

In the intense COVID pandemic year of 2020, this overall pattern flipped, with elevated primary forest loss in protected areas, again largely due to major fires in Bolivia. Thus, indigenous territories had the lowest primary forest loss rate followed by protected areas (0.15% and 0.19%, respectively) in 2020.

Averaged across all four years, protected areas had the lowest primary forest loss rate (0.11%), closely followed by indigenous territories (0.14%). Outside of these critical areas (red), the primary forest loss rate was more than double (0.30%). The lowest primary forest loss rates (less than 0.10%) occurred in the protected areas of Ecuador and Peru (0.01% and 0.03%, respectively), and indigenous territories of Colombia (0.07%).

Country Results

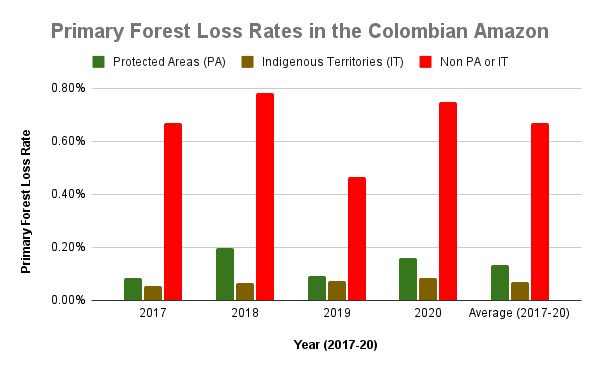

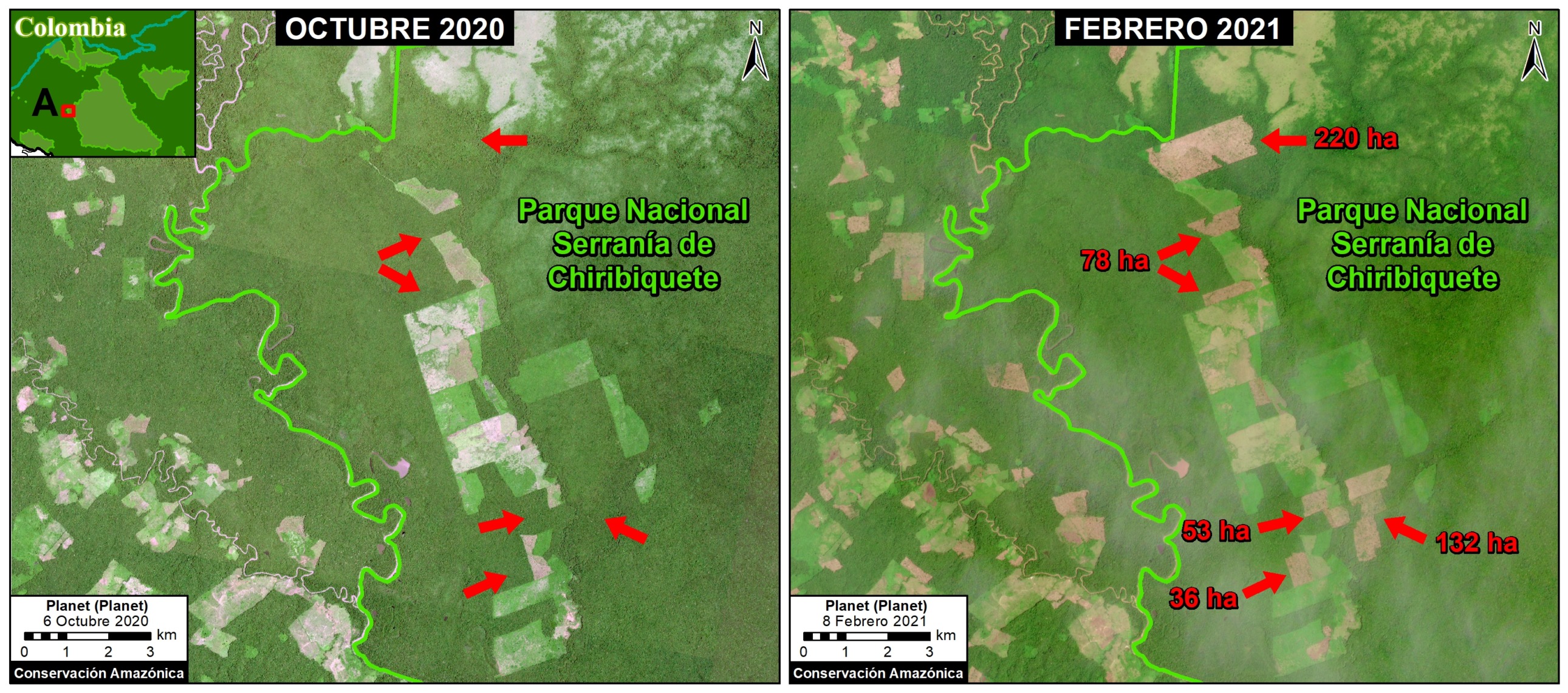

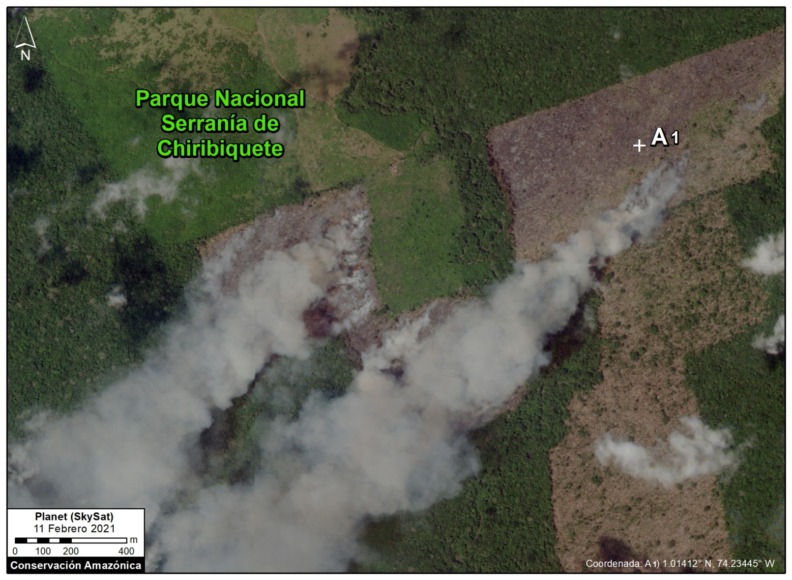

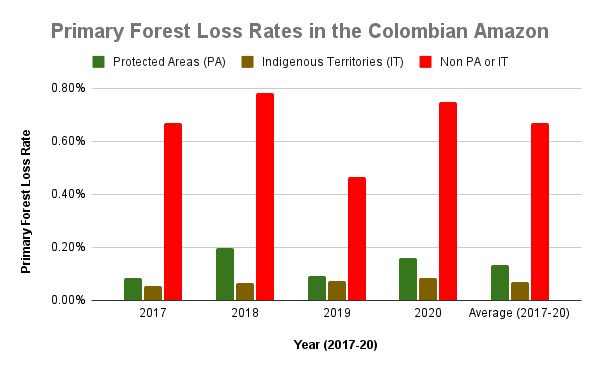

Figure 2. Primary forest loss rates in the Colombian Amazon.

Colombian Amazon

Colombia had, by far, the highest primary forest loss rates outside protected areas and indigenous territories (averaging 0.67% across all four years).

By contrast, Colombian indigenous territories had one of the lowest primary forest loss rates across the western Amazon (averaging 0.07% across all four years).

The primary forest loss rates for protected areas were on average nearly double that of indigenous territories (mostly due to the high deforestation in Tinigua National Park), but still much lower than non-protected areas.

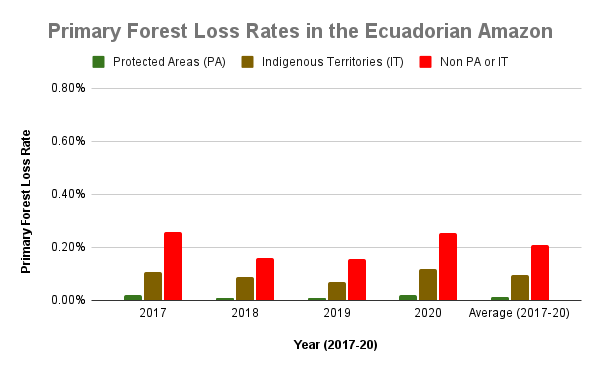

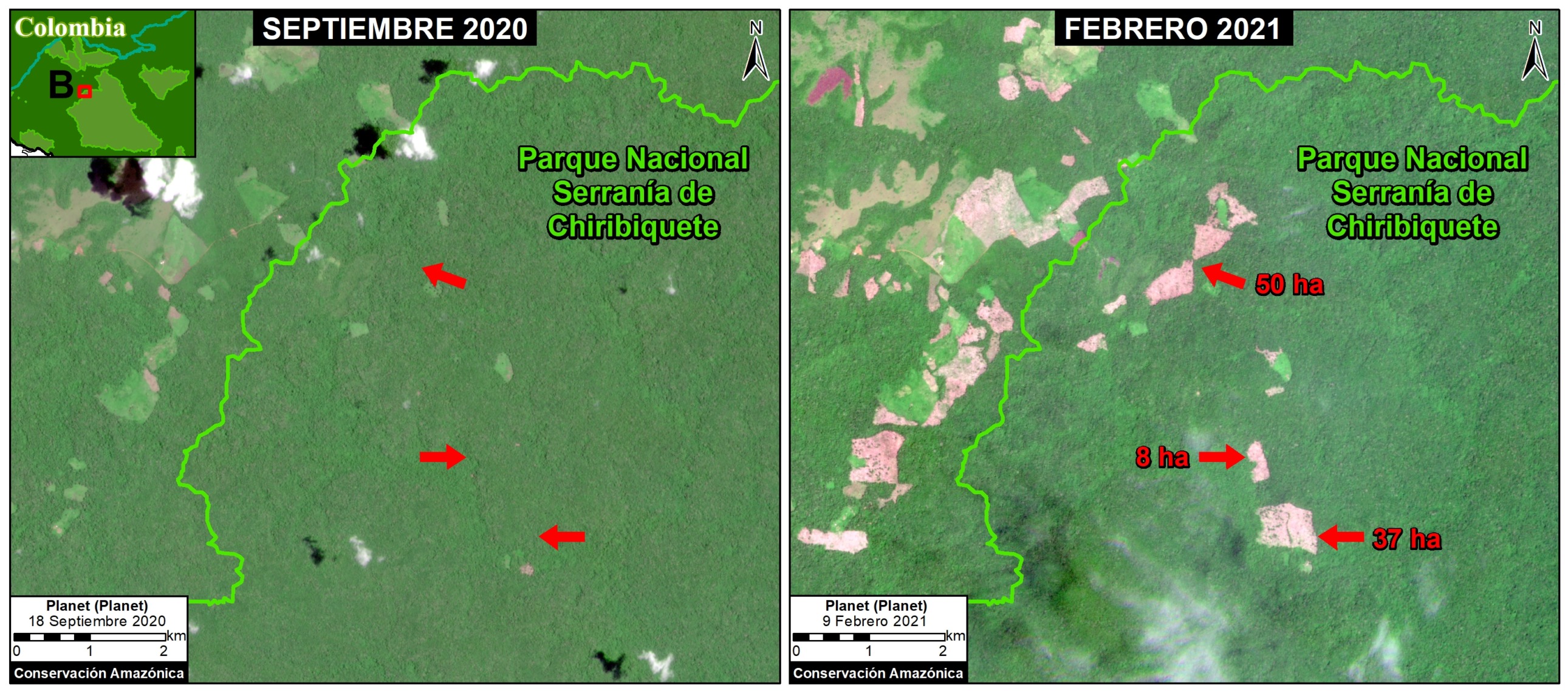

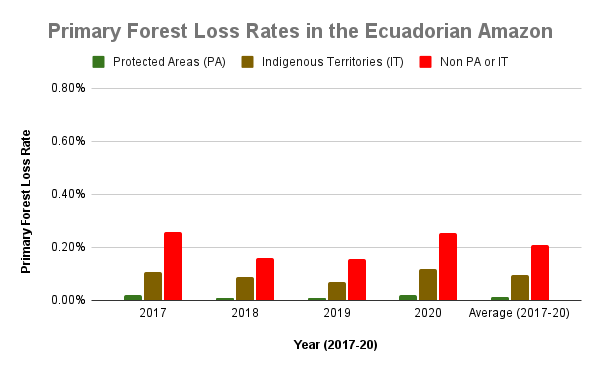

Figure 3. Primary forest loss rates in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Ecuadorian Amazon

Overall, Ecuador had the lowest primary forest loss rates across all three categories.

Protected areas had the lowest primary forest loss rate of any category across the western Amazon (averaging 0.01% across all four years).

Indigenous territories also had relatively low primary forest loss rates, averaging half that of outside protected areas and indigenous territories (0.10% vs 0.21%, respectively).

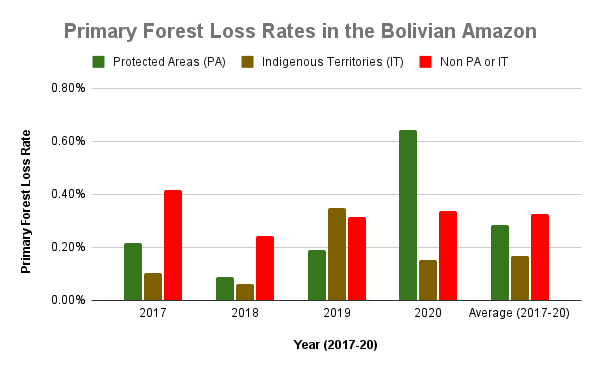

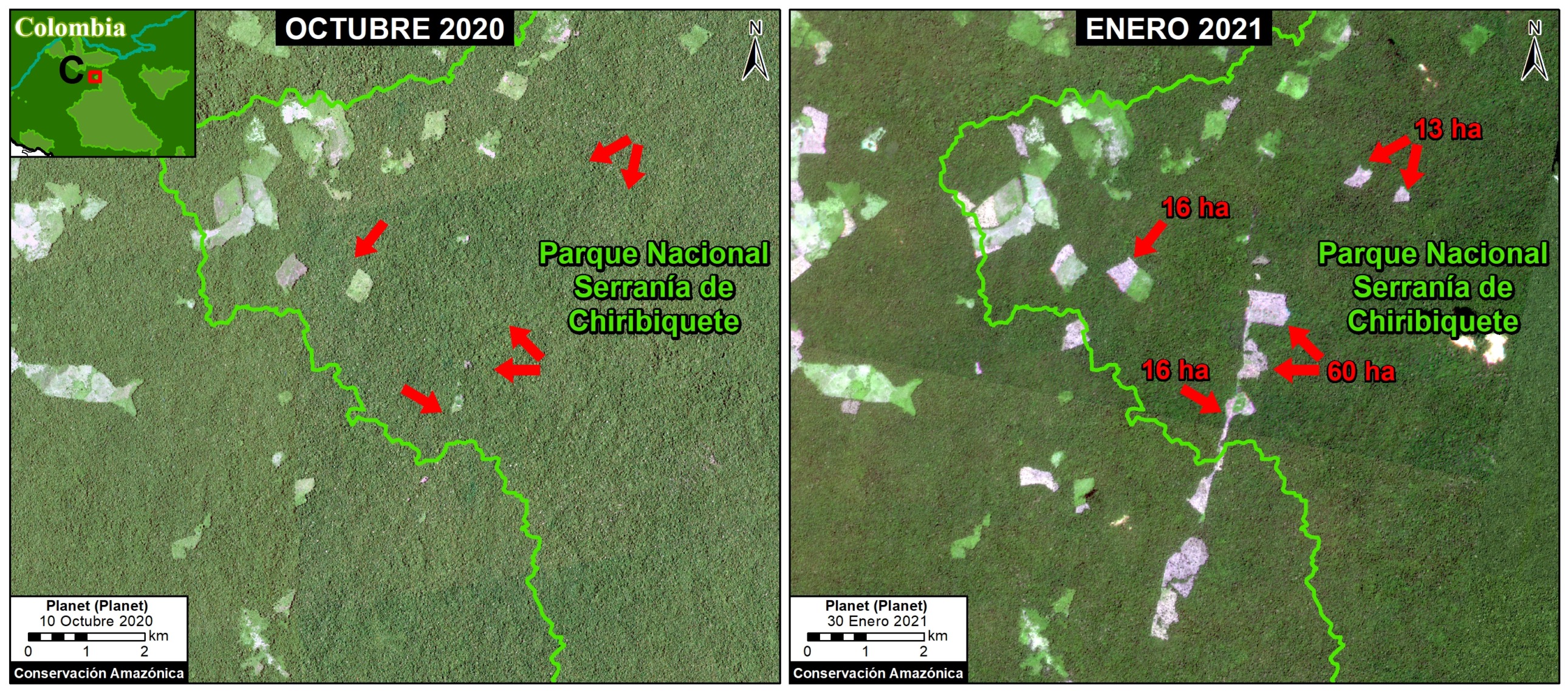

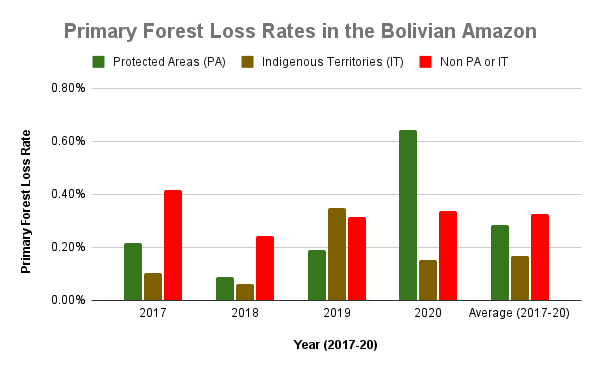

Figure 4. Primary forest loss rates in the Bolivian Amazon.

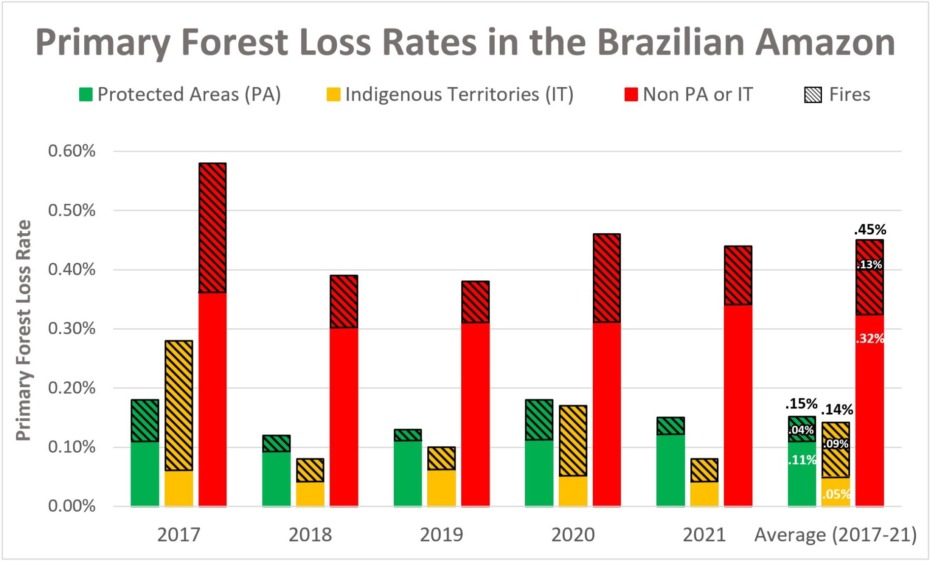

Bolivian Amazon

Bolivia had the most dynamic results, largely due to intense fire seasons in 2019 and 2020. Indigenous territories had the lowest primary forest loss rates, with 2019 being the only exception, due to large fires in the Santa Cruz department that affected the Monte Verde indigenous territory.

Protected areas had the lowest primary forest loss rate in 2019, but in extreme contrast, the highest the following year in 2020, also due to large fires in the Santa Cruz department that affected Noel Kempff Mercado National Park.

Overall, primary forest loss was highest outside protected areas and indigenous territories (averaging 0.33% across all four years).

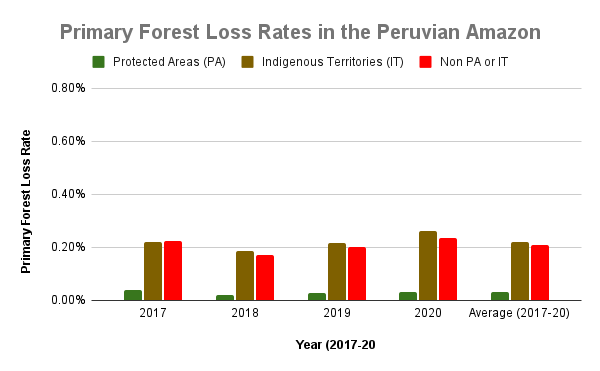

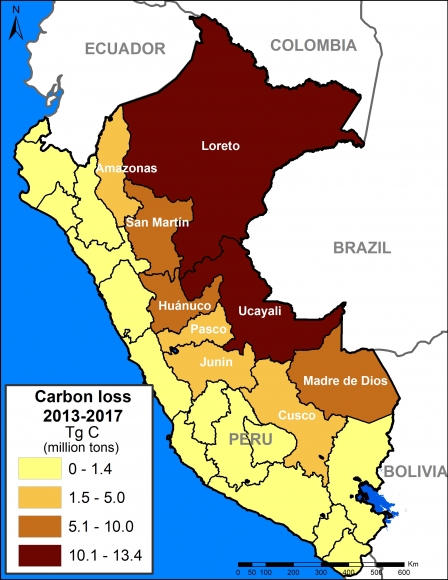

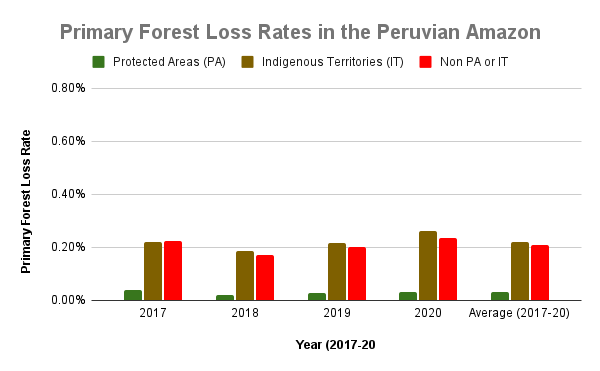

Figure 5a. Primary forest loss rates in the Peruvian Amazon. Data: UMD.

Peruvian Amazon

Following Ecuador, Peru also had relatively low primary forest loss rates, particularly in protected areas (averaging 0.03% across all four years).

Primary forest loss in indigenous territories (that is, combined data for native communities and Territorial/Indigenous Reserves for groups in voluntary isolation) was surprisingly high, similar to that of areas outside protected areas across all four years. For example, in 2020, elevated primary forest loss was concentrated in several titled native communities in the regions of Amazonas, Ucayali, Huánuco, and Junín.

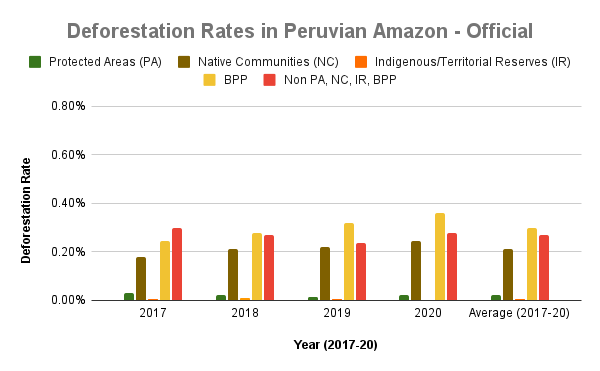

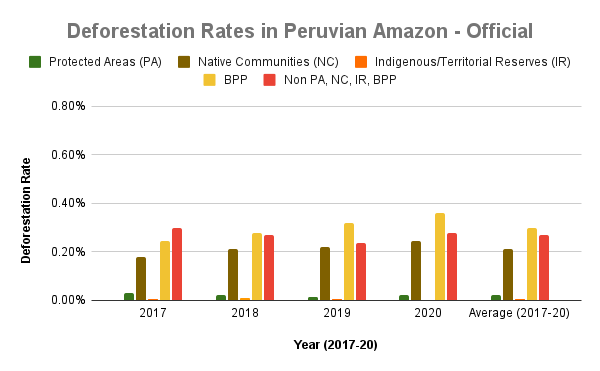

Figure 5b. Deforestation rates in the Peruvian Amazon. Data: MINAM/Geobosques.

As noted above, we conducted a deeper analysis for the Peruvian Amazon, using deforestation data produced by the Peruvian government and adding the additional category of long-term forestry lands (known as Permanent Production Forests, or BPP in Spanish) (see Annex map).

We also separated the data for indigenous territories into native communities and Territorial/Indigenous Reserves for groups in voluntary isolation, respectively.

These data also show that deforestation was lowest in the remote Territorial/Indigenous Reserves, closely followed by protected areas (0.01% vs 0.02% across all four years, respectively). Deforestation in titled native communities was 0.21% across all four years. Surprisingly, deforestation was higher in the forestry lands than areas outside protected areas and indigenous territories (0.30% vs 0.27% across all four years).

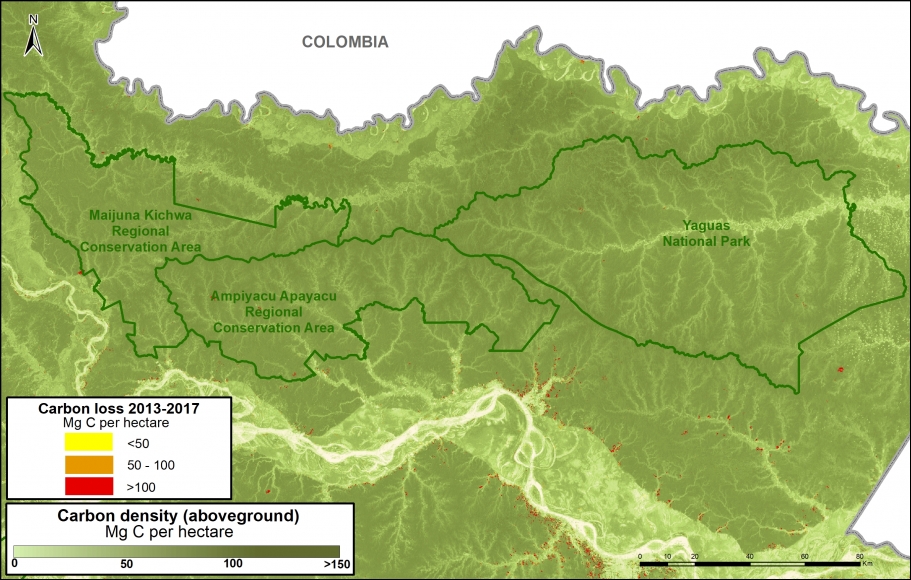

Annex – Peruvian Amazon

Annex – Peruvian Amazon

The following map shows added detail for Peru, most notably the inclusion of long-term forestry lands (known as Permanent Production Forests, or BPP in Spanish).

*Methodology

To estimate deforestation across all three categories, we used annual forest loss data (2017-20) from the University of Maryland (Global Land Analysis and Discovery GLAD laboratory) to have a consistent source across all four countries (Hansen et al 2013).

We obtained this data, which has a 30-meter spatial resolution, from the “Global Forest Change 2000–2020” data download page. It is also possible to visualize and interact with the data on the main Global Forest Change portal.

It is important to note that these data include both human-caused deforestation and forest loss caused by natural forces (landslides, wind storms, etc…).

We also filtered this data for only primary forest loss, following the established methodology of Global Forest Watch. Primary forest is generally defined as intact forest that has not been previously cleared (as opposed to previously cleared secondary forest, for example). We applied this filter by intersecting the forest cover loss data with the additional dataset “primary humid tropical forests” as of 2001 (Turubanova et al 2018). For more details on this part of the methodology, see the Technical Blog from Global Forest Watch (Goldman and Weisse 2019).

Thus, we often use the term “primary forest loss” to describe the data.

Data presented as primary forest loss or deforestation rate is standardized per the total area covered of each respective category. For example, to properly compare raw forest loss data in areas that are 100 hectares vs 1,000 hectares total size respectively, we divide by the area to standardize the result.

Our geographic range included four countries of the western Amazon and consists of a combination of the Amazon watershed limit (most notably in Bolivia) and Amazon biogeographic limit (most notably in Colombia) as defined by RAISG. See Base Map above for delineation of this hybrid Amazon limit, designed for maximum inclusion.

Additional data sources include: National and state/deprartment level protected areas: RUNAP 2020 (Colombia), SNAP 2017 & RAISG 2020 (Ecuador), SERNAP & ACEAA 2020 (Bolivia), and SERNANP 2020 (Peru).

Indigenous Territories: RAISG 2020 (Colombia, Ecuador, and Bolivia), and MINCU & ACCA 2020 (Peru). For Peru, this includes titled native communities and Indigenous/Territorial Reserves for indigenous groups in voluntary isolation.

For the additional analysis in Peru, we used deforestation data from MINAM/Geobosques (note this is actual deforestation and not primary forest loss) and BPP data from SERFOR. We also separated data from titled native communities and Territorial/Indigenous Reserves for groups in voluntary isolation.

Acknowledgements

We thank M. MacDowell (AAF) A. Folhadella (ACA), J. Beavers (ACA), S. Novoa (ACCA), and D. Larrea (ACEAA) for their helpful comments on this report.

This work was supported by the Andes Amazon Fund (AAF), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), and International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC).

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N, Silman M (2021) Protected Areas & Indigenous Territories Effective Against Deforestation in the Western Amazon. MAAP: 141.