We continue our ongoing series about carbon in the Amazon.

In part 1 (MAAP #215), we introduced a new dataset (Planet’s Forest Carbon Diligence) with wall-to-wall estimates for aboveground carbon at an unprecedented 30-meter resolution between 2013 and 2022. In part 2 (MAAP #217), we highlighted which parts of the Amazon are currently home to the highest (peak) carbon stocks. In part 3 (MAAP #220), we showed key cases of carbon loss (deforestation) and gain across the Amazon.

A key finding from this series is that the Amazon biome is teetering between a carbon source and sink. That is, historically the Amazon has functioned as a critical sink, with its forests accumulating carbon if left undisturbed. However, relative to the 2013 baseline, the Amazon flipped to a source during the high deforestation, drought, and fire seasons of 2015-2017. It then rebounded as a narrow carbon sink in 2022.

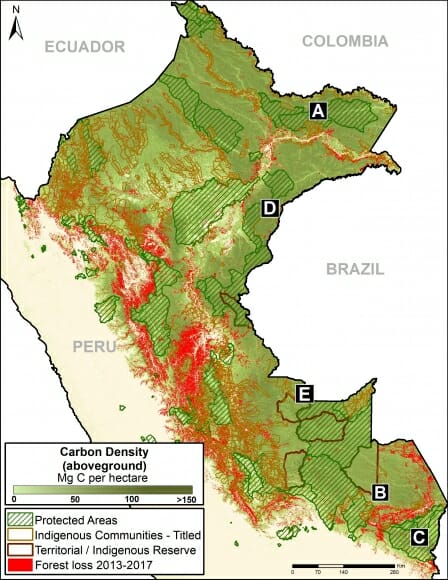

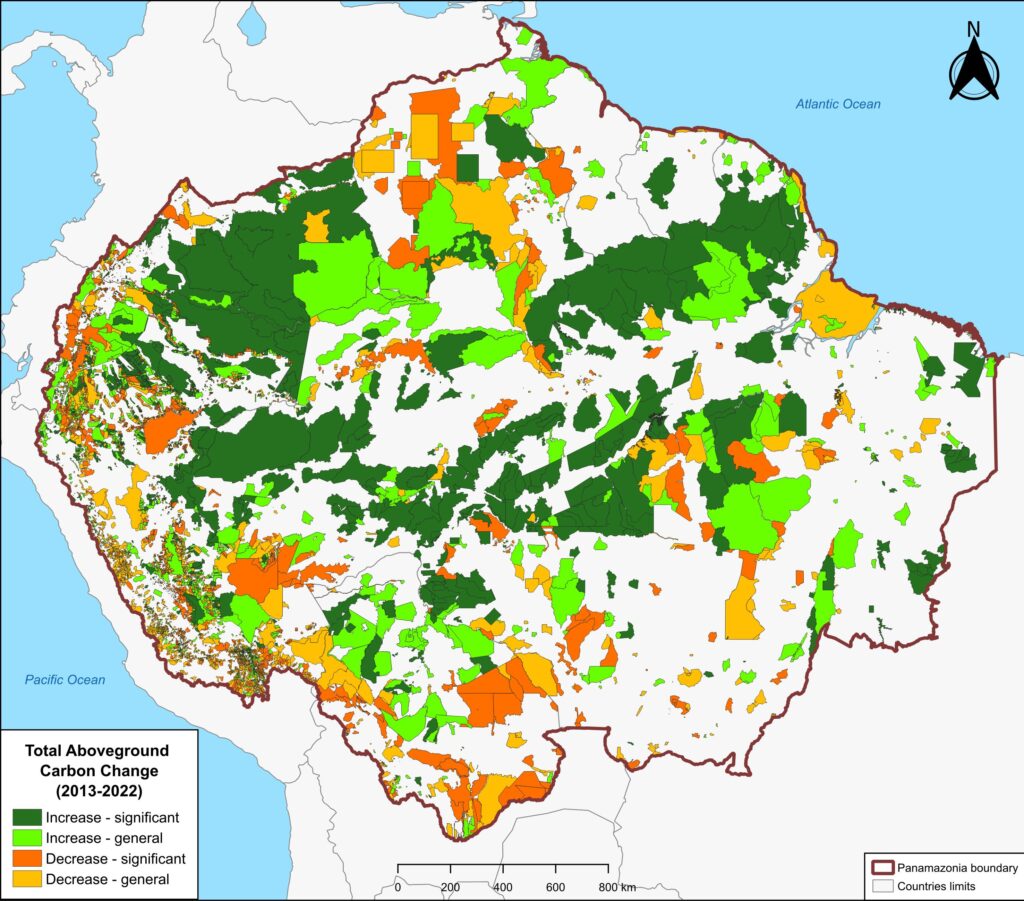

Here, in part 4, we focus on the importance of aboveground carbon in protected areas and Indigenous territories, which together cover 49.5% (414.9 million hectares) of the Amazon biome (see Figure 1).

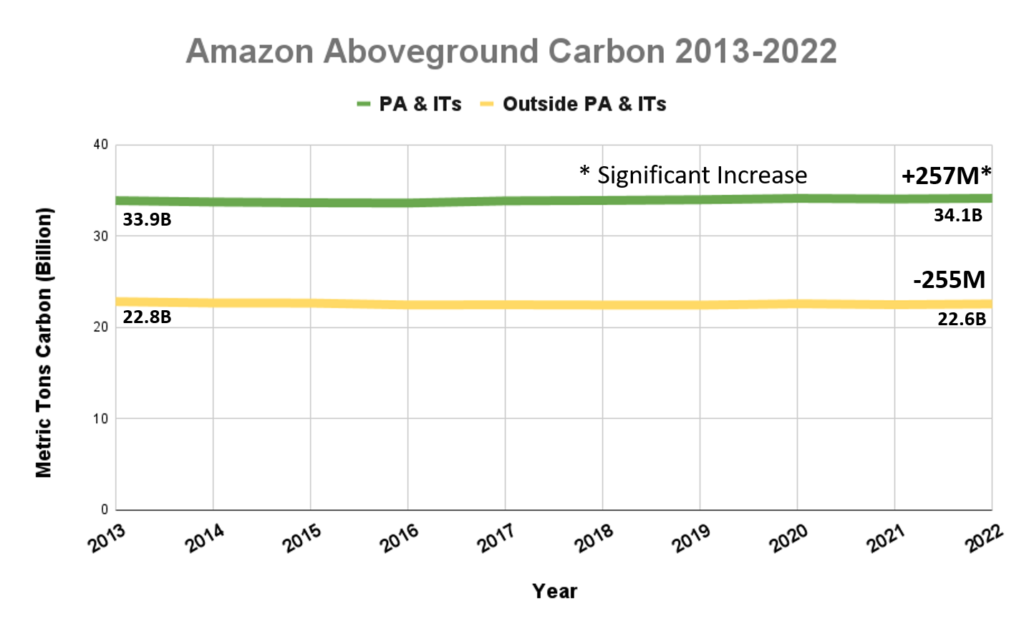

We find that, as of 2022, Amazonian protected areas and Indigenous territories contained 34.1 billion metric tons of aboveground carbon (60% of the Amazon’s total). Importantly, in the ten years between 2013 and 2022, they functioned as a significant carbon sink, gaining 257 million metric tons.

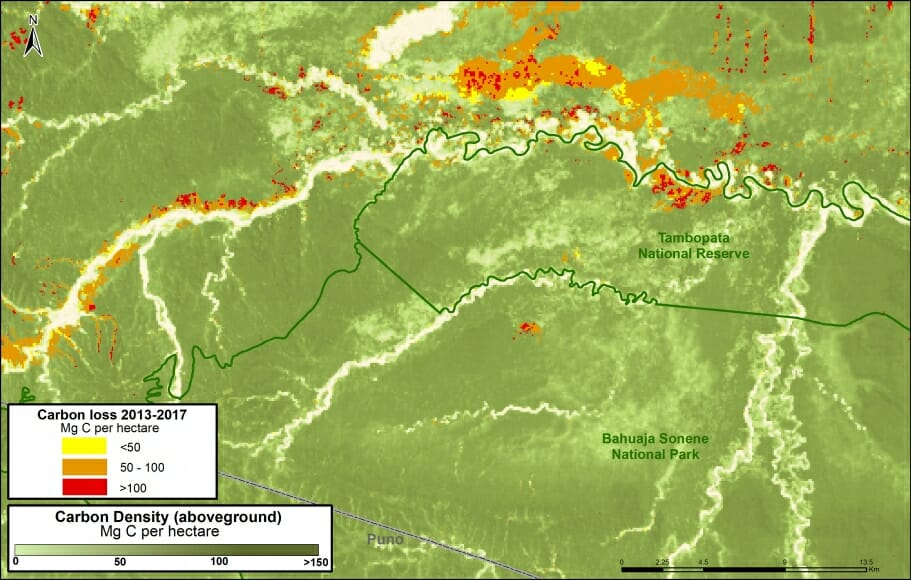

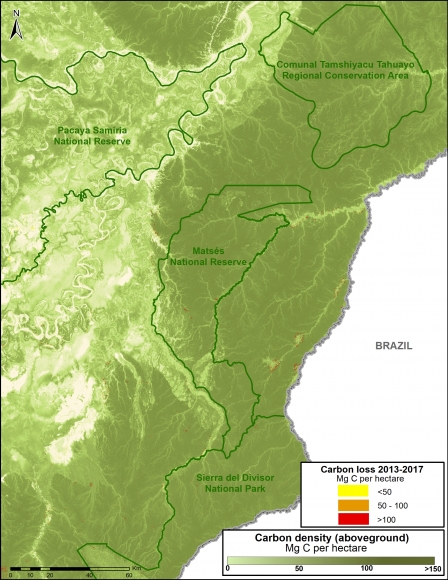

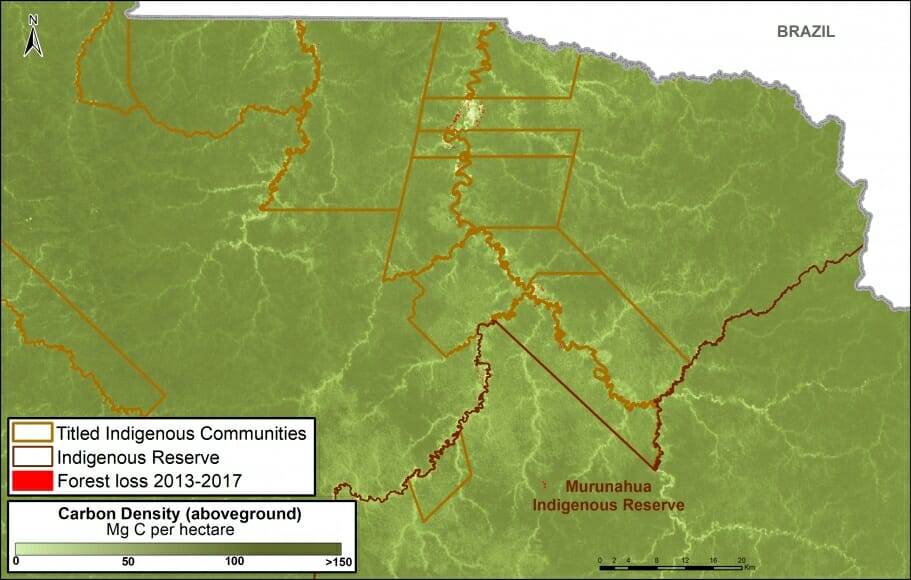

With this data, we can also analyze aboveground carbon for each protected area and Indigenous territory. For example, Figure 1 illustrates aboveground carbon loss vs. gain for each protected area and Indigenous territory during the 10-year period of 2013 – 2022 (see details below).

Below, we further explain and illustrate the key findings.

Amazon-wide & Country-level Results

Amazonian protected areas and Indigenous territories currently cover nearly half (49.5%) of the Amazon biome, but contain 60% of the aboveground carbon. Together they contained 34.1 billion metric tons of aboveground carbon as of 2022, gaining 257 million metric tons since 2013, thus functioning as a carbon sink (Figure 2).1,2

In contrast, areas outside of protected areas and Indigenous territories (424 million hectares) contained 22.6 billion metric tons of aboveground carbon as of 2022, losing 255 million metric tons since 2013, thus functioning as an overall carbon source.

Thus, the carbon sink function of protected areas and Indigenous territories narrowly offsets the emissions in the rest of the Amazon.

We emphasize that the protected areas and Indigenous territories functioned as a significant carbon sink (p-value = 0.01), while the outside areas were not a significant source (p-value= 0.15).

Regarding results by country, protected areas and Indigenous territories were significant carbon sinks in Colombia, Brazil, Suriname, and French Guiana (Guyana gained carbon but not significantly). In contrast, they were significant carbon sources in Bolivia and Venezuela (Peru and Ecuador lost carbon but not significantly).

Individual Protected Area & Indigenous Territory Results

Figure 1 (see above) illustrates total aboveground carbon loss vs. gain for each protected area and Indigenous territory during the 10-year period of 2013 – 2022.

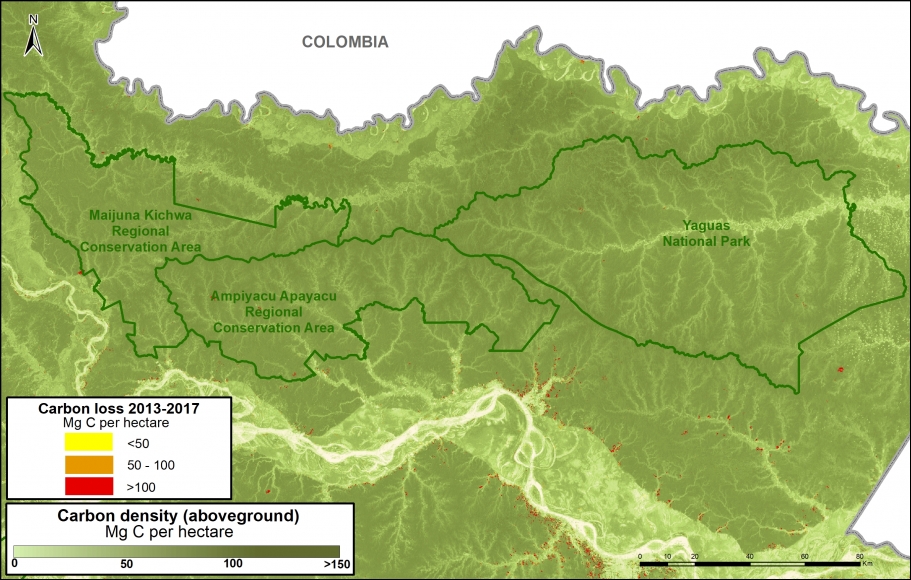

Overall, we found 1,103 areas that served as significant carbon sinks (dark green) during this period (238 protected areas and 865 Indigenous territories). These areas are concentrated in the northern and central Amazon. See Annex 1 for a list of specific areas that were significant carbon sinks.

It is important to note that deforestation pressures currently threaten several of these significant carbon sinks, including Chiribiquete National Park and Nukak-Maku Indigenous Reserve in Colombia, Sierra del Divisor National Park in Peru, and Canaima National Park in Venezuela.

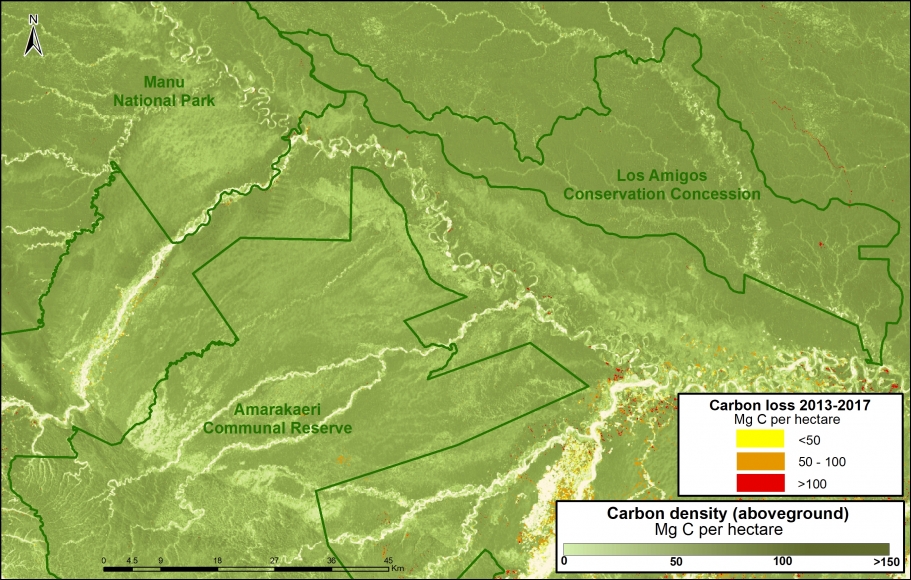

In contrast, we found 1,439 areas (156 protected areas and 1,283 Indigenous territories) that served as significant carbon sources. It is important to note that some areas with little documented deforestation, such as Alto Purus National Park, may have carbon loss from natural causes.

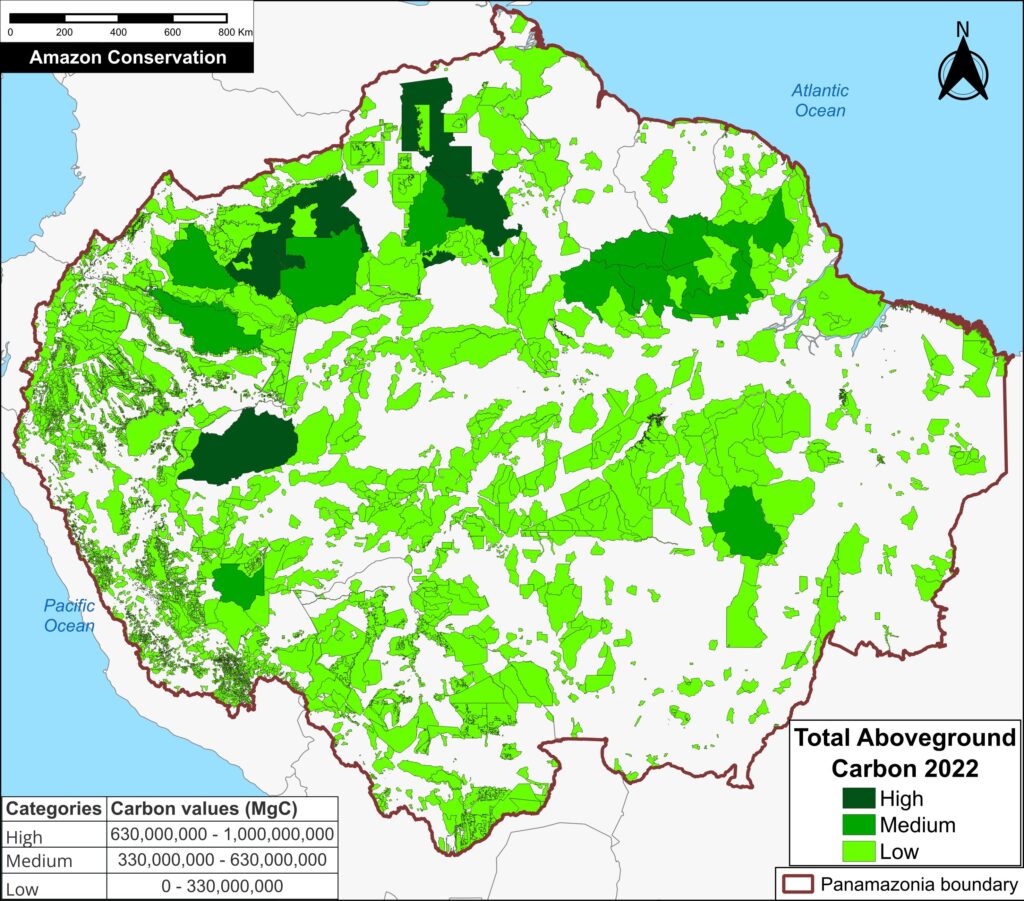

Figure 3 offers the most recent snapshot of total aboveground carbon stocks in each protected area and Indigenous territory.

It presents data for 2022 categorized into three groups of High, Medium, and Low. Note that the highest carbon totals (over 330 million metric tons) are concentrated across the large designated areas of the northern Amazon.

These High and Medium carbon areas may be considered to have the highest overall conservation value purely in terms of total carbon.

See Annex 1 for specific areas with the highest carbon stocks as of 2022.

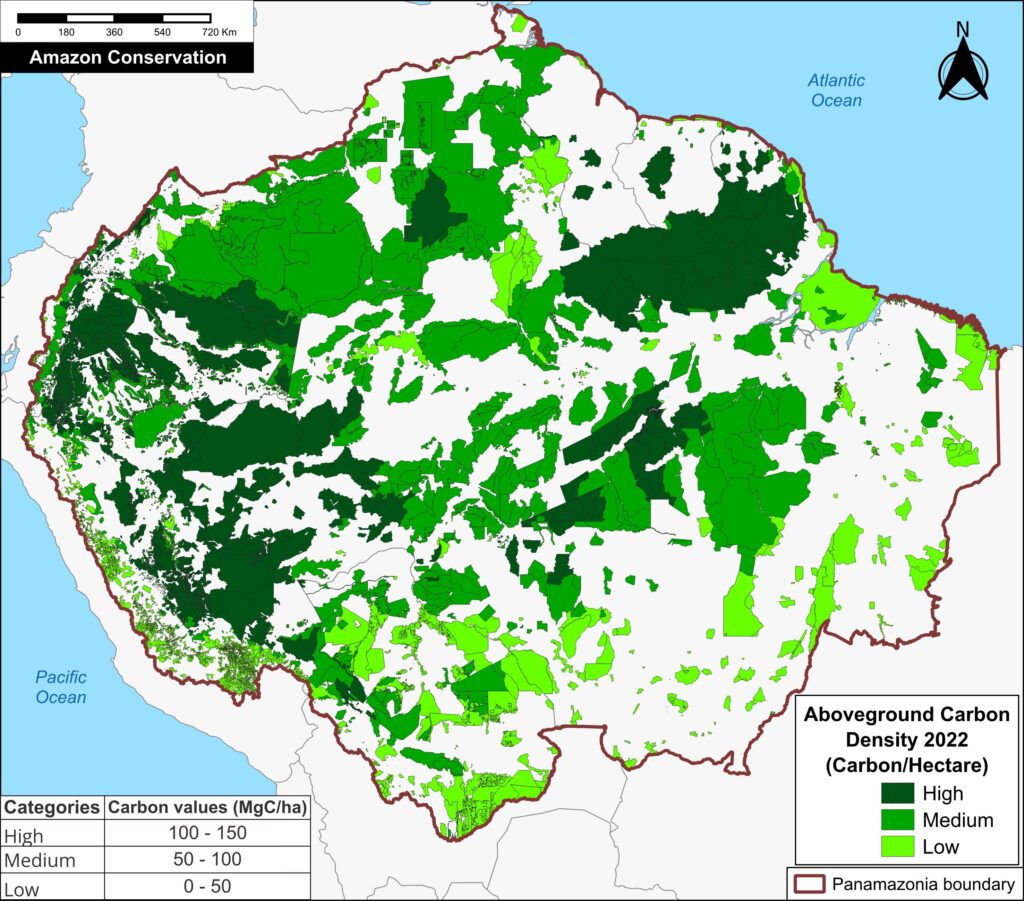

Finally, Figure 4 also displays the most recent data (2022) in each protected area and Indigenous territory, but standardized for area (aboveground carbon/hectare).

Note that the highest carbon totals (over 50 metric tons per hectare) are more evenly concentrated across the Amazon.

These High and Medium carbon areas may be considered to have the highest carbon conservation value per hectare.

Policy Implications:

Unlocking the Climate Value of Protected Areas and Indigenous Territories in the Amazon

Policy and finance for tropical forests as a climate solution have largely focused on reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+). These efforts have made important strides in slowing and directing finance to tackle forest loss, particularly in high-deforestation regions. However, this emphasis on avoided emissions overlooks a critical component of the global carbon cycle: the carbon sink function (gaining of carbon over time) of primary tropical forests — which this analysis using Planet’s Forest Carbon Diligence data show is both measurable and significant.

This omission leaves a major flux in the carbon system—ongoing carbon sequestration in old-growth forests—outside the scope of existing market or non-market incentives. Critically, many of these carbon-absorbing forests are already located within established protected areas and indigenous territories. These areas are globally recognized for their importance in biodiversity conservation and for the stewardship provided by Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

As global attention increasingly turns to engineered carbon removal strategies such as BECCS (Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage) and Direct Air Capture, there is an urgent need to recognize that Amazonian forests are already performing this function—naturally and at scale. Yet the value of Protected Areas and Indigenous territories as a potent carbon sink is neither monetized nor rewarded under current frameworks, unless they can demonstrate that they are under threat from deforestation or degradation in order to access REDD+ finance. An emerging exception is the High Integrity Forests Investment Initiative (HIFOR), which recognizes the value of carbon sequestration in old-growth forests, but does not generate tradable credits for each ton absorbed.5 The Tropical Forests Forever Fund (TFFF) proposed by Brazil for adoption at COP 30, would also reward forest countries at a rate of approximately US$ 4.00/year for every hectare of tropical forest they protect, regardless of whether they are under threat.6

To date, however, protected areas and Indigenous territories, despite their proven climate contribution, often lack the financial support necessary to ensure long-term effectiveness and resilience. As a result, they often face chronic underfunding,7 limiting their long-term effectiveness and resilience. Policy innovation is needed to close this gap and integrate the carbon sink function of mature forests into funding mechanisms for forest protection. Doing so would unlock meaningful incentives for the continued, long-term stewardship of these high-carbon ecosystems and would ensure that one of the planet’s most effective natural climate solutions receives the attention and resources it deserves.

Annex 1

Specific areas that were significant carbon sinks include:

Otishi, Sierra del Divisor, Güeppí-Sekime and Yaguas National Parks, Matsés, and Pucacuro National Reserves, Ashaninka Communal Reserve, and Cordillera Escalera and Alto Nanay- Pintuyacu Chambira Regional Conservation Area, Matses, Pampa Hermosa, and Yavarí – Tapiche Indigenous Reserves, and Kugapakori, Nahua, Nanti Territorial Reserve in Peru;

Amacayacu, Chiribiquete, Cahuinari, Rio Pure, and Yaigoje Apaporis National Parks, Nukak Natural Reserve, Amazonas Forest Reserve, and Putumayo and Nukak-Maku, Yaigoje Rio Apaporis and Vaupes Indigenous Reserve in Colombia;

Campos Amazônicos, Juruena, Mapinguari, Nascentes do Lago Jari, Serra do Divisor, and Montanhas do Tumucumaque National Parks, Amanã, Aripuanã, Crepori, Tapajós, and Tefé National Forests in Brazil, Itaituba and Jatuarana National Forests, and Alto Rio Negro, Baú, Aripuanã, Aripuanã, Apyterewa, Mundurucu, and Vale do Javari Indigenous Territories in Brazil.

Achuar Indigenous Territory and Zona Intangible Tagaeri – Taromenane in Ecuador; Manuripi Heath National Reserve and Takana, Takana II, and Yuracare Indigenous Reserves in Bolivia; Central Suriname and Sipaliwini Nature Reserves in Suriname; Canaima National Park in Venezuela; and Parc Amazonien de Guyane National Park in French Guiana,

Specific areas with the highest carbon stocks, as of 2022, include:

Alto Purús, Manu, Sierra del Divisor, and Cordillera National Parks in Peru; Chiribiquete National Park in Colombia; Montanhas do Tumucumaque, Pico da Neblina, Jaú, and Juruena National Parks and Yanomami, Menkragnoti, Kayapó, Mundurucu, and Vale do Javari Indigenous Territories in Brazil; Caura and Canaima National Parks in Venezuela; and Parc Amazonien de Guyane National Park in French Guiana;

Methodology

We analyzed Planet Forest Carbon Diligence, a cutting-edge new dataset from the satellite-based company Planet, featuring a 10-year historical time series (2013 – 2022) with wall-to-wall estimates for aboveground carbon density at 30-meter resolution.3,4

One notable caveat of this data is that it does not distinguish aboveground carbon loss from natural vs human-caused drivers, so additional information may be incorporated to understand the context of each area.

Based on these data, annual aboveground carbon values were estimated in Amazonian protected areas and Indigenous territories to obtain a time series for 2013-2022. In addition, the Mann-Kendall test was used to analyze trends in the generated time series.

Our data source for protected areas and Indigenous territories is from RAISG (Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information), a consortium of civil society organizations in the Amazon countries. This source (accessed in December 2024) contains spatial data for 5,943 protected areas and Indigenous territories, covering 414.9 million hectares across the Amazon.

We determined that many of these areas (4,000) did not include creation date metadata, prohibiting any time-series control for that variable. Instead, we used the most current extent of protected areas and Indigenous territories as a proxy for those that existed from 2013 to 2022.

There was substantial overlap between protected areas and Indigenous territories, but we accounted for this to avoid double counting of the overlapping areas.

The aboveground carbon values for protected areas and Indigenous territories were calculated for each country and then summed across the Amazon.

The remaining areas were combined into the category of “Outside protected areas and Indigenous territories” and also calculated for each country and summed across the Amazon.

Our geographic range for the Amazon is a hybrid designed for maximum inclusion: biogeographic boundary (as defined by RAISG) for all countries, except for Bolivia and Peru, where we use the watershed boundary, and Brazil, where we use the Legal Amazon boundary. Our area estimate for this definition of the Amazon biome is 839.2 million hectares.

Notes

1 Breaking down the results by category, protected areas contained nearly 21.1 billion metric tons of aboveground carbon as of 2022, gaining over 204 million metric tons since 2013, while Indigenous territories contained over 16.8 billion metric tons of aboveground carbon as of 2022, gaining over 132 million metric tons since 2013. Note that protected areas and Indigenous territories overlap in many areas.

2 Standardizing for area (that is, calculating the results per hectare), protected areas and Indigenous territories contained 82.2 metric tons of aboveground carbon per hectare as of 2022, gaining a net 0.6 metric tons per hectare since 2013. In contrast, areas outside of protected areas and Indigenous territories contained 53.2 metric tons of aboveground carbon per hectare as of 2022, losing a net 0.6 metric tons per hectare since 2013.

3 Anderson C (2024) Forest Carbon Diligence: Breaking Down the Validation and Intercomparison Report. https://www.planet.com/pulse/forest-carbon-diligence-breaking-down-the-validation-and-intercomparison-report/

4 In terms of the limitations of Planet’s Forest Carbon Diligence data, Duncanson et al (2025) recently wrote a Letter in Science focused on spatial resolution for forest carbon maps. Given the natural constraint of the size of a tree, they discuss the challenge of pixel-level validation below 5 meters for forest carbon monitoring. The authors state that spatial resolution should at minimum exceed the crown diameter of a typical large tree, which is about 20 meters for tropical forests. In this sense, the 30-meter product exceeds this limitation.

Duncanson et al (2025) Spatial resolution for forest carbon maps. Science 387: 370-71.

5 WCS High Integrity Forest Investment Initiative (HIFOR): The Science Basis

6 https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2025-04-04/too-big-to-fell-brazil-takes-trees-to-wall-street?cmpid=BBD040425_GR

7 UNEP-WCMC, IUCN, and NGS. (2022). Protected Planet Report 2022. Cambridge, UK: UNEP-WCMC.

Acknowledgments

Through a generous sharing agreement with the satellite company Planet, we have been granted access to this data across the entire Amazon biome for the analysis presented in this series.

We thank colleagues from the following organizations for helpful comments on this report: Planet, Conservación Amazónica – ACCA, Conservación Amazónica -ACEAA, Gaia Amazonas, Ecociencia, and Instituto del Bien Común.

We especially thank colleagues at Conservación Amazónica – ACCA for help with the 10-year data analysis.

This report was made possible by the generous support of the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD)

Citation

Bodin B, Finer M, Castillo H, Mamani N (2025) Carbon in the Amazon (part 4): Protected Areas & Indigenous Territories. MAAP: 225.