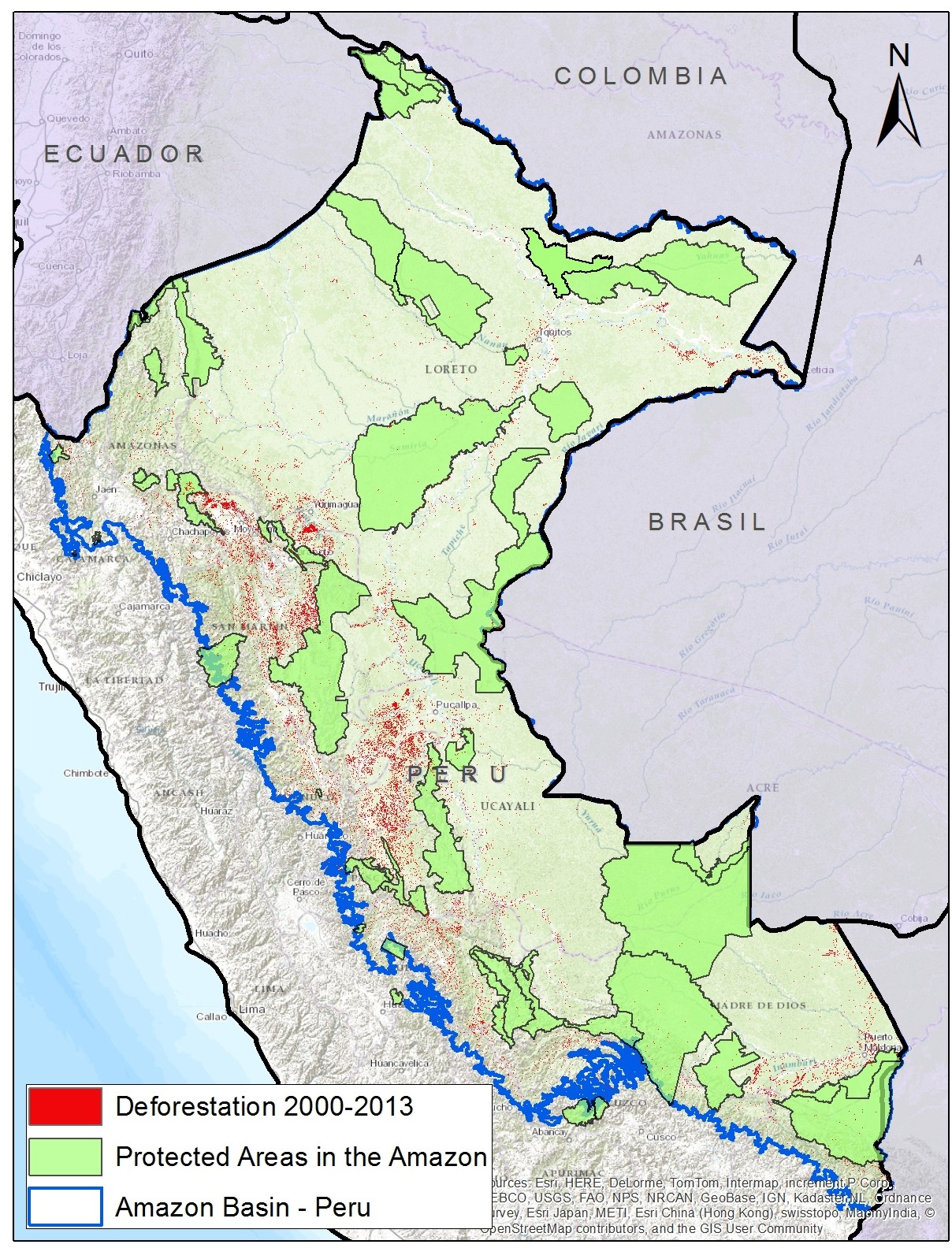

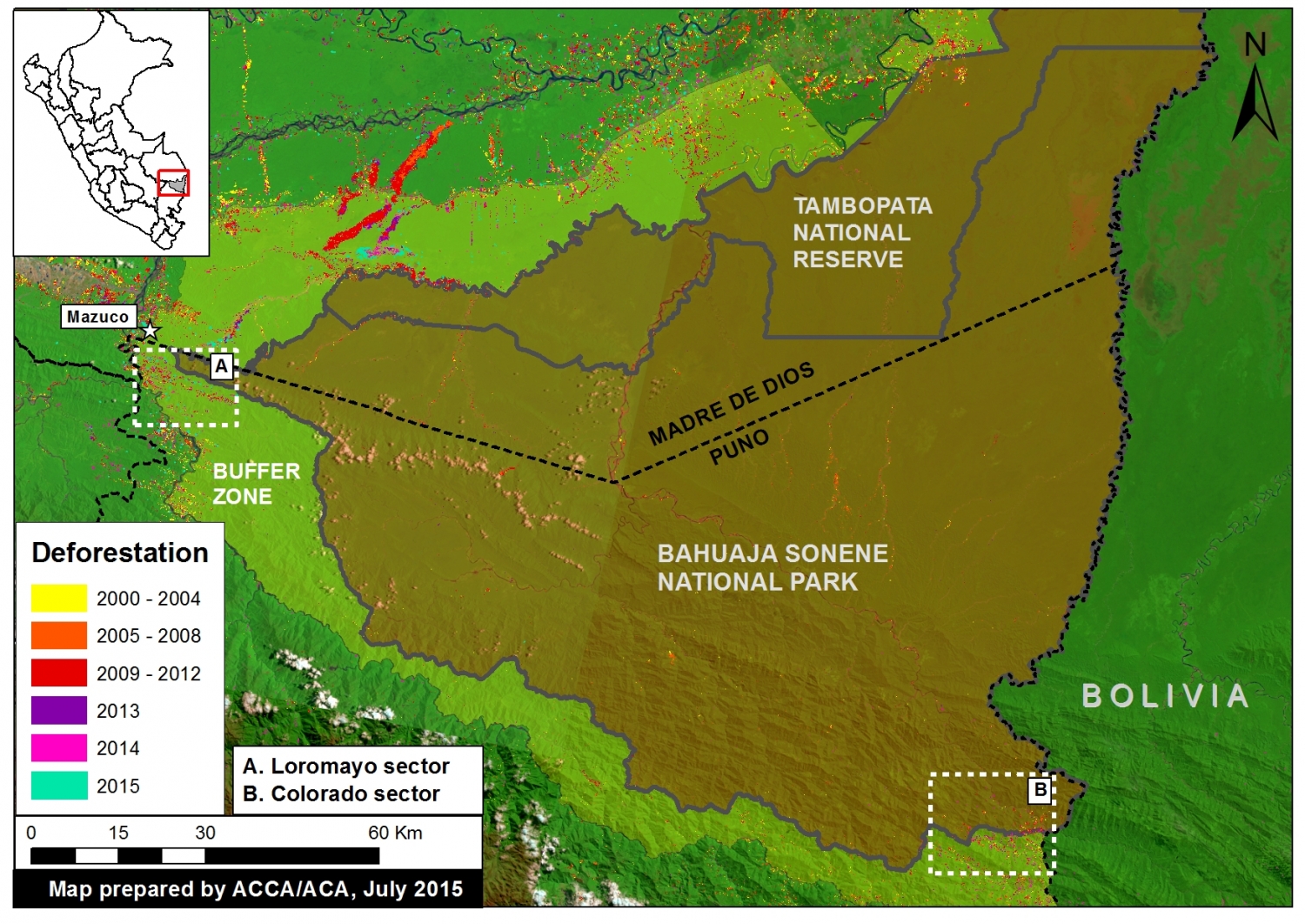

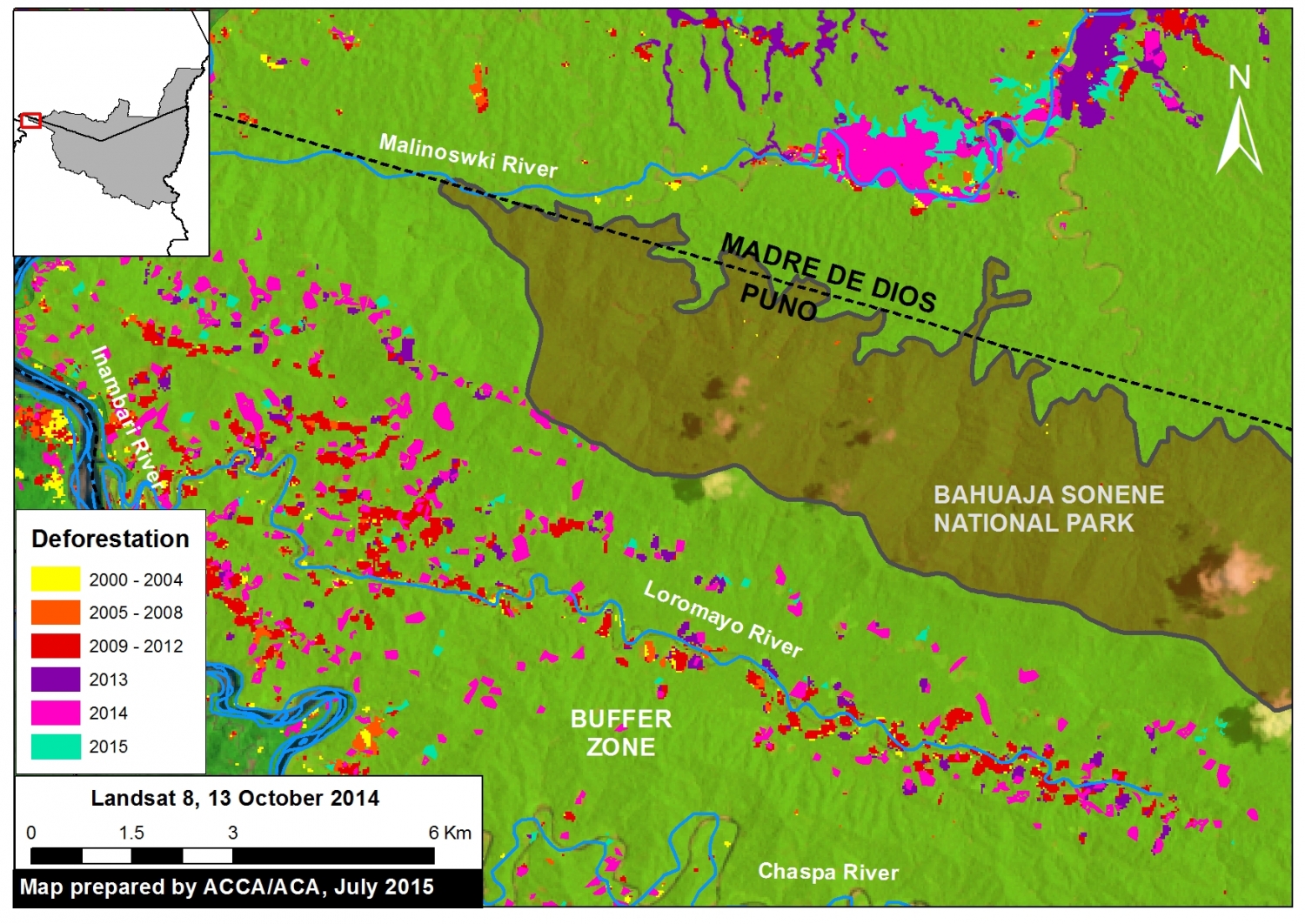

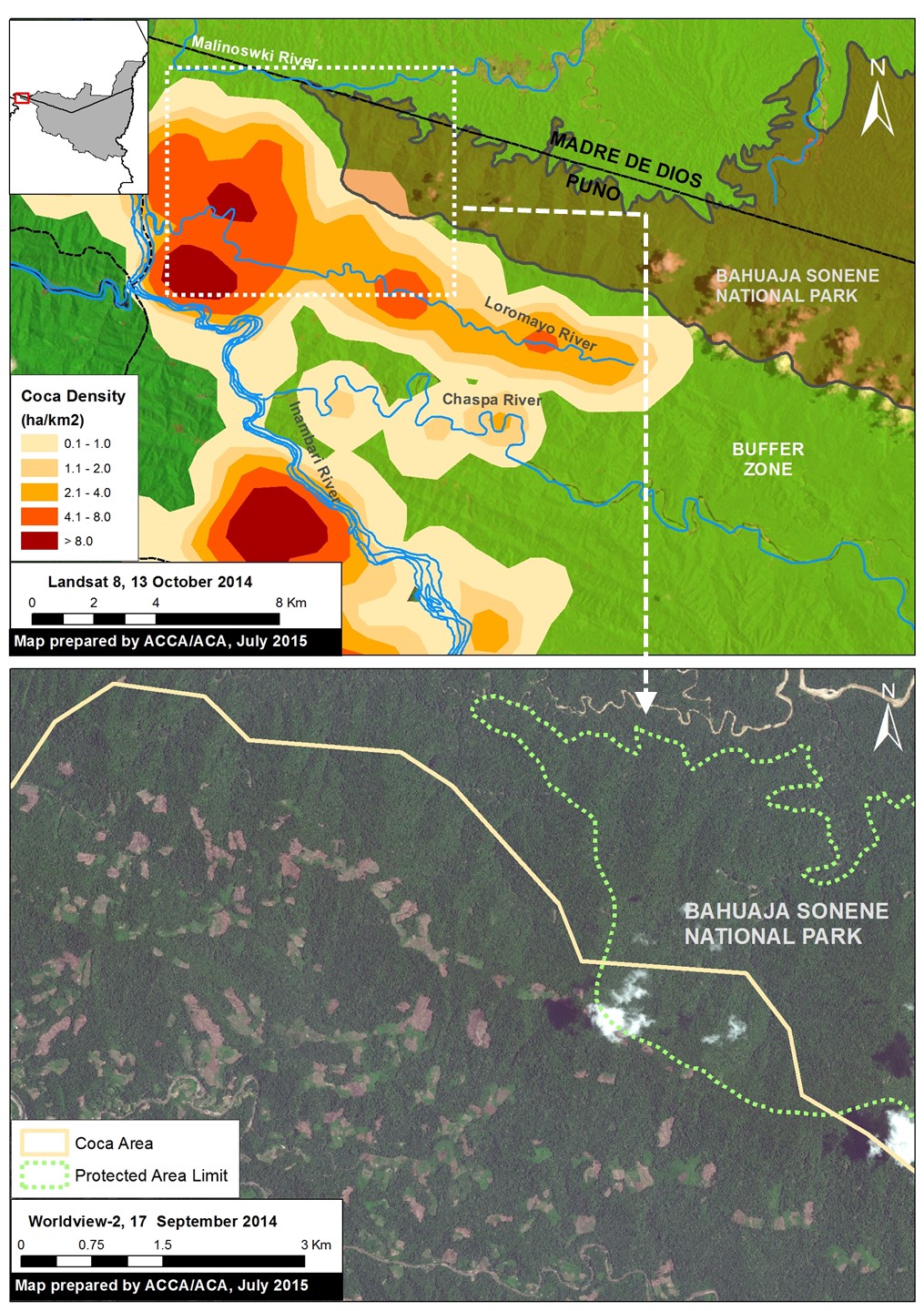

In MAAP #1, we described the expansion of deforestation through February 2015 in La Pampa, a gold mining hotspot located in the Madre de Dios region in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Since then, we have obtained a new high-resolution image showing the current situation (as of late July 2015) in great detail in La Pampa.

Here in MAAP #12, we present an analysis with the following three objectives: 1) Update data for the recent expansion of gold mining deforestation in La Pampa, 2) show a series of high-resolution images that illustrate the scale and magnitude of current gold mining operations, and 3) illustrate how the Tambopata National Reserve currently represents a good defense against deforestation expansion.

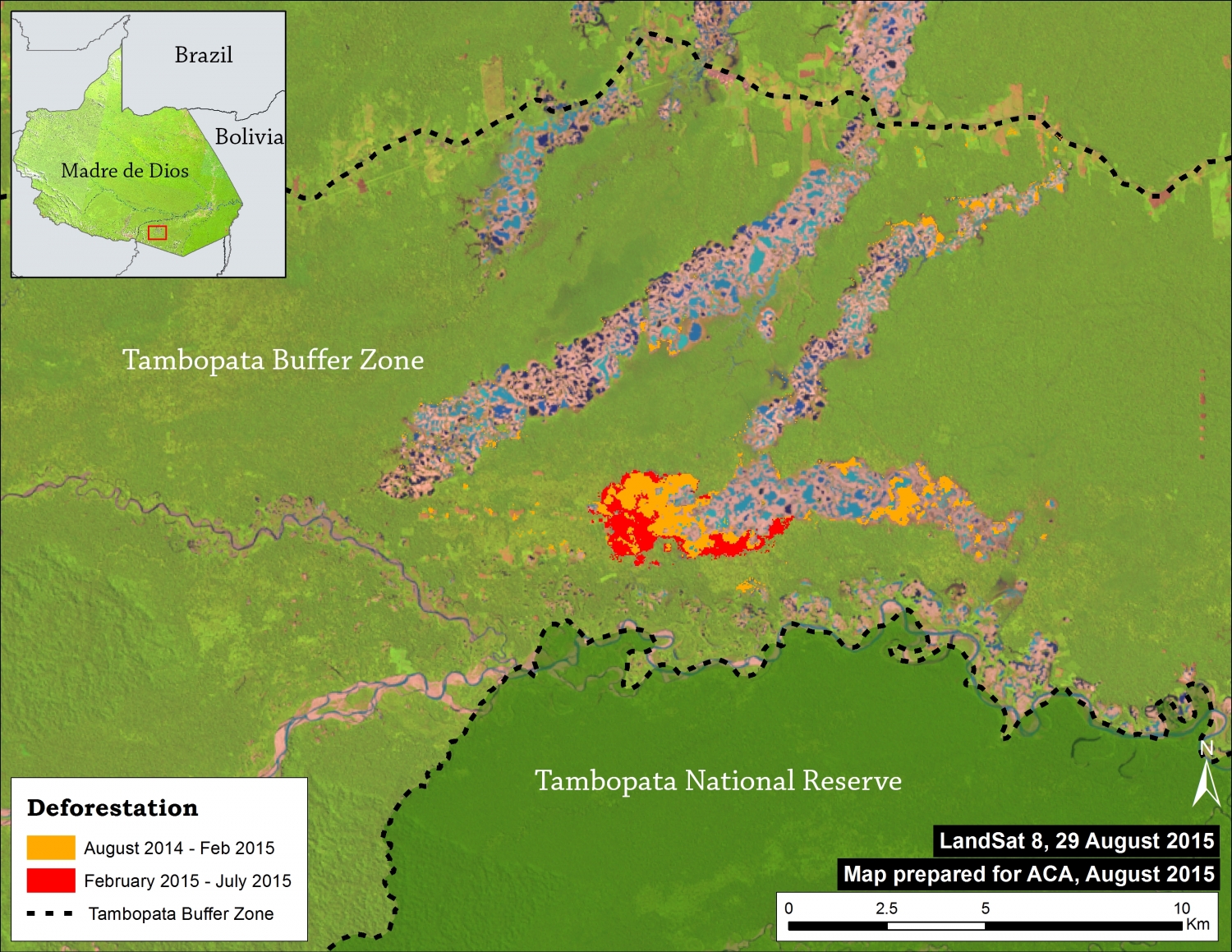

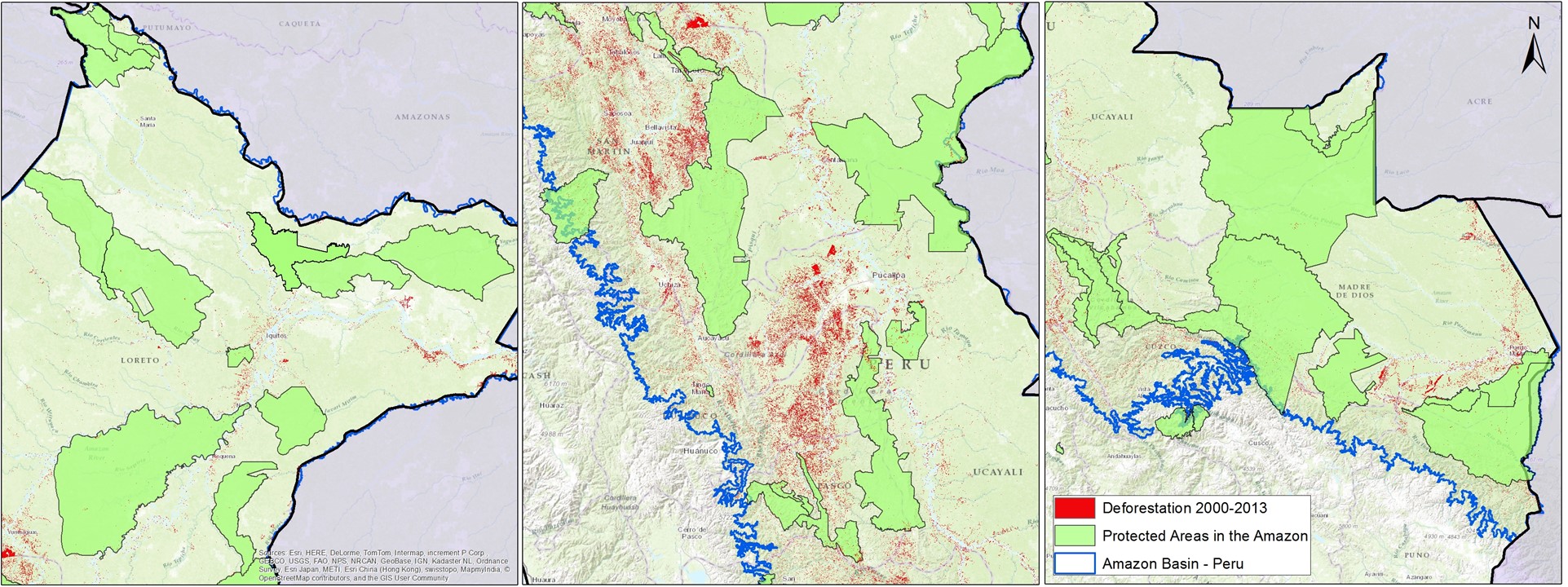

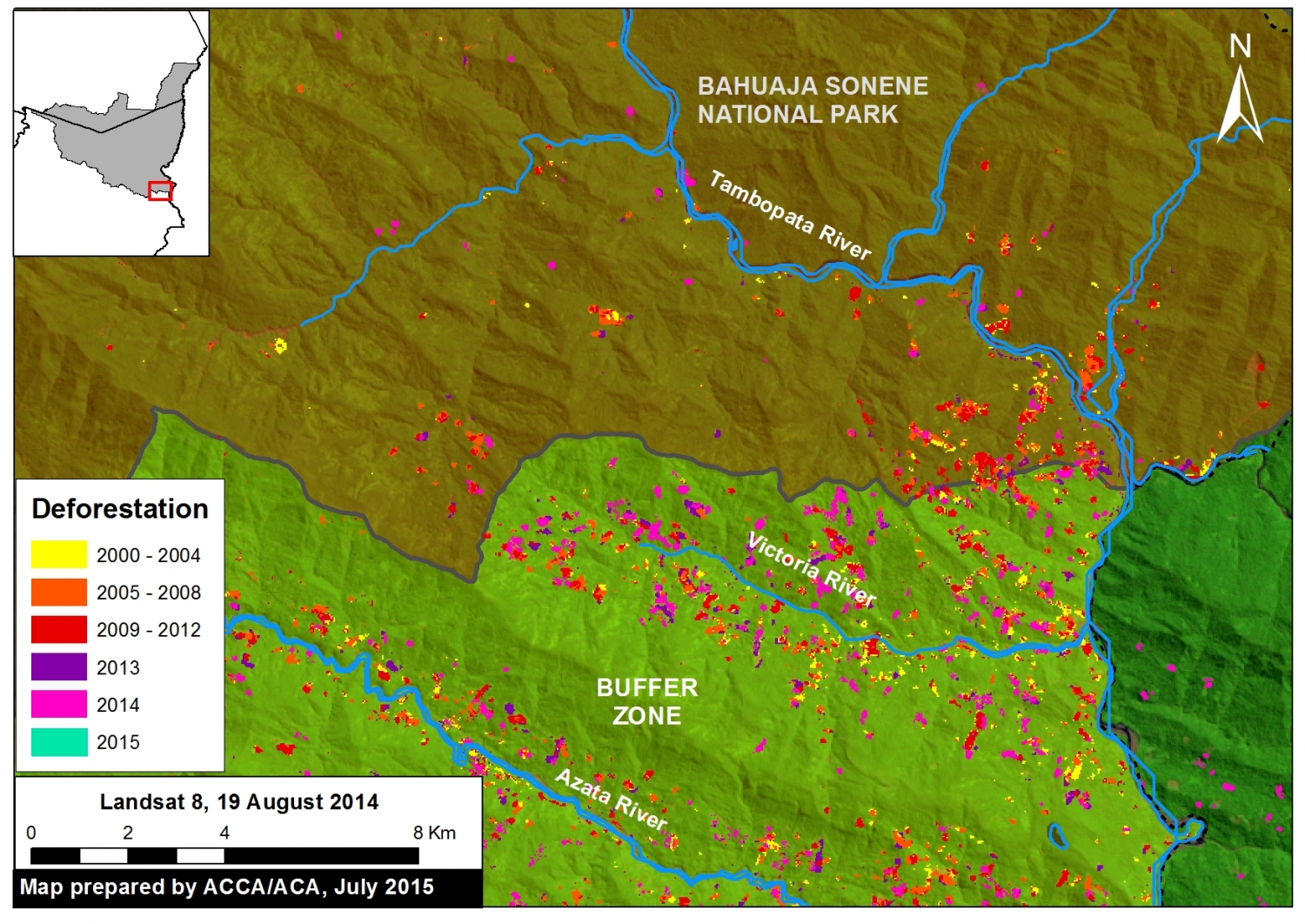

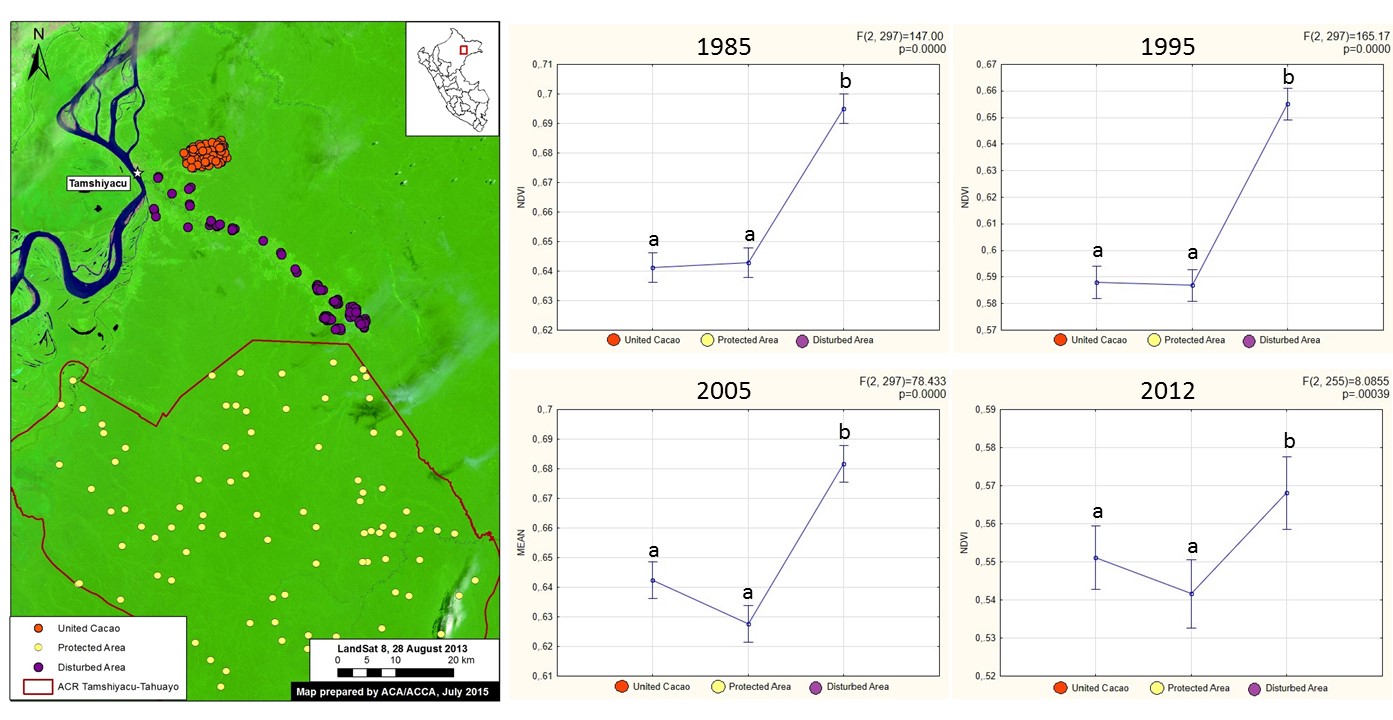

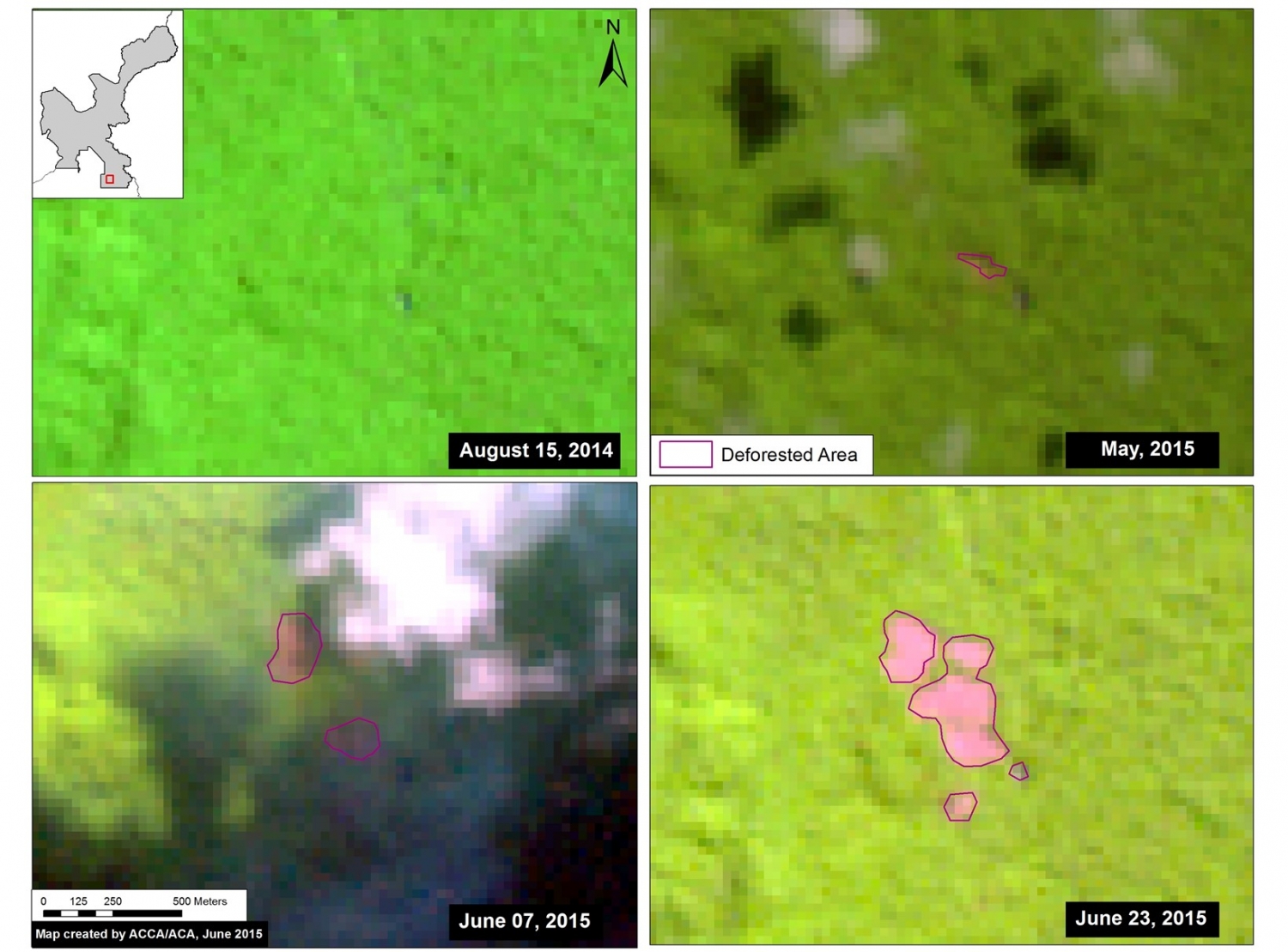

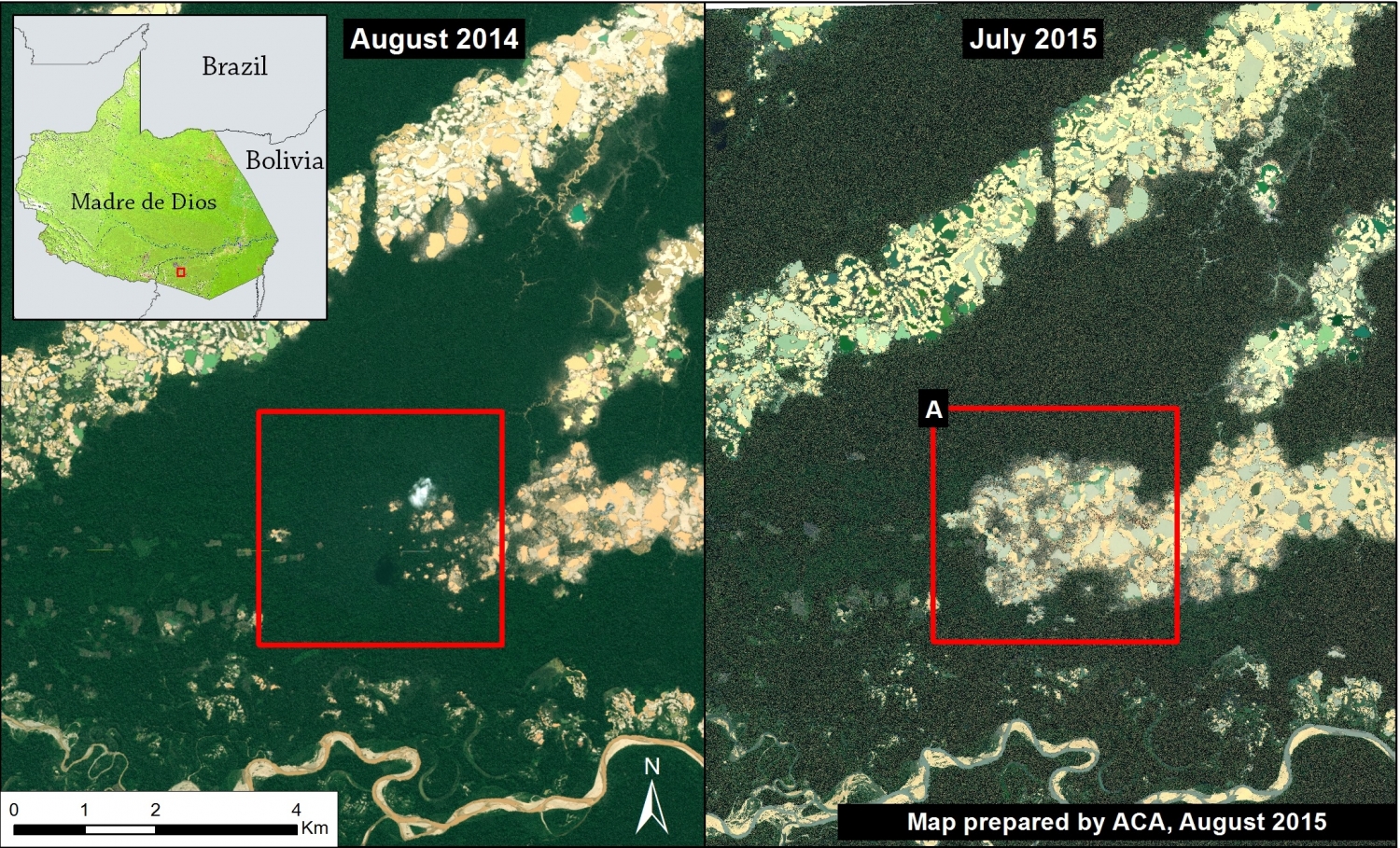

Image 12a shows, in high resolution, the expansion of gold mining deforestation in La Pampa during the last year (between August 2014 and July 2015). The red square indicates the main zone of deforestation.

Deforestation 2014-15

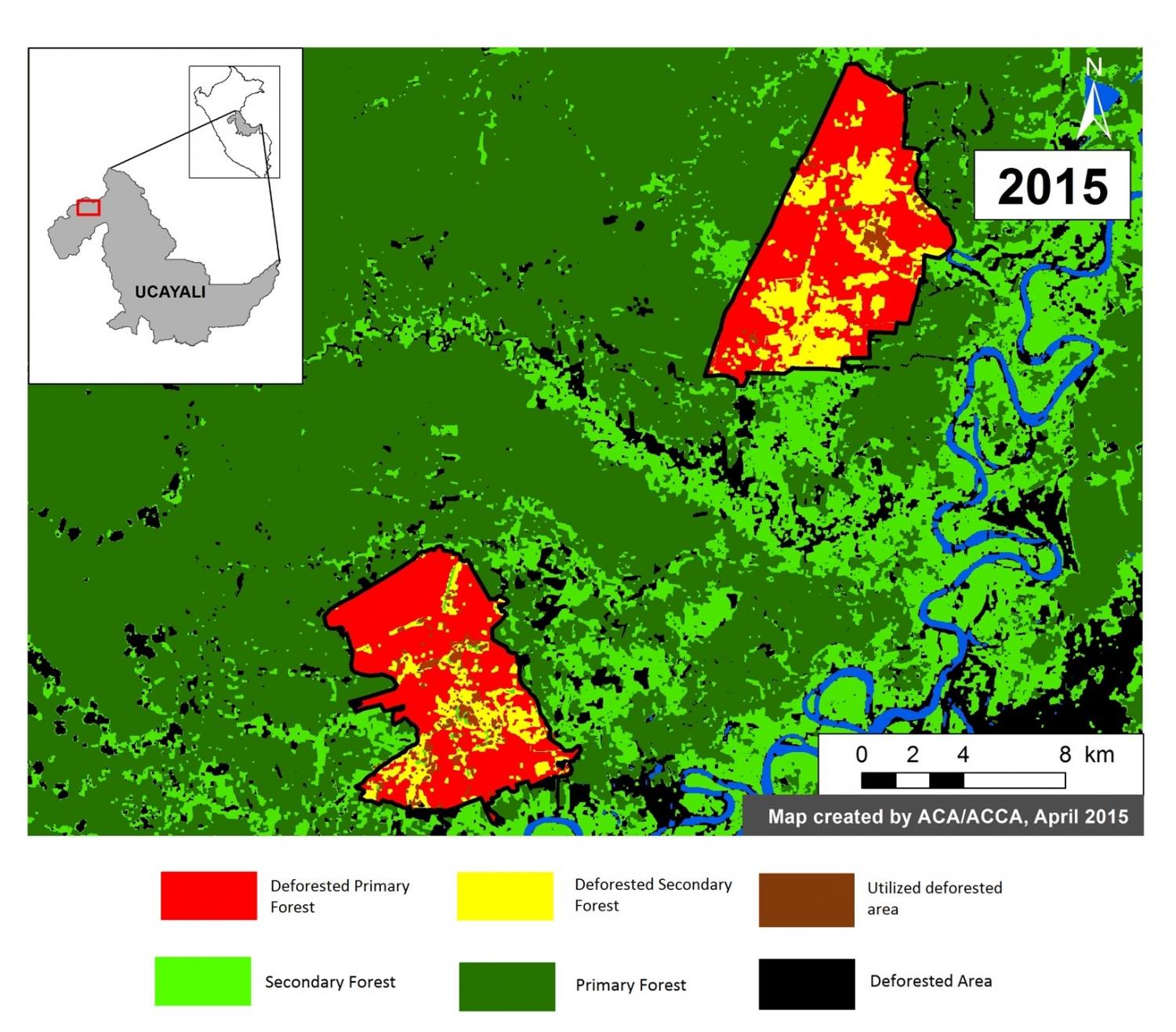

Image 12b shows the CLASlite results of the expansion of gold mining deforestation in La Pampa during the past year (between August 2014 and July 2015). We found deforestation of 725 hectares (Ha) in the last year, including 224 Ha since February (the date of the last image analyzed in the MAAP #1). This equates to nearly 1,000 soccer fields of deforestation throughout the year.

High Resolution View – July 2015

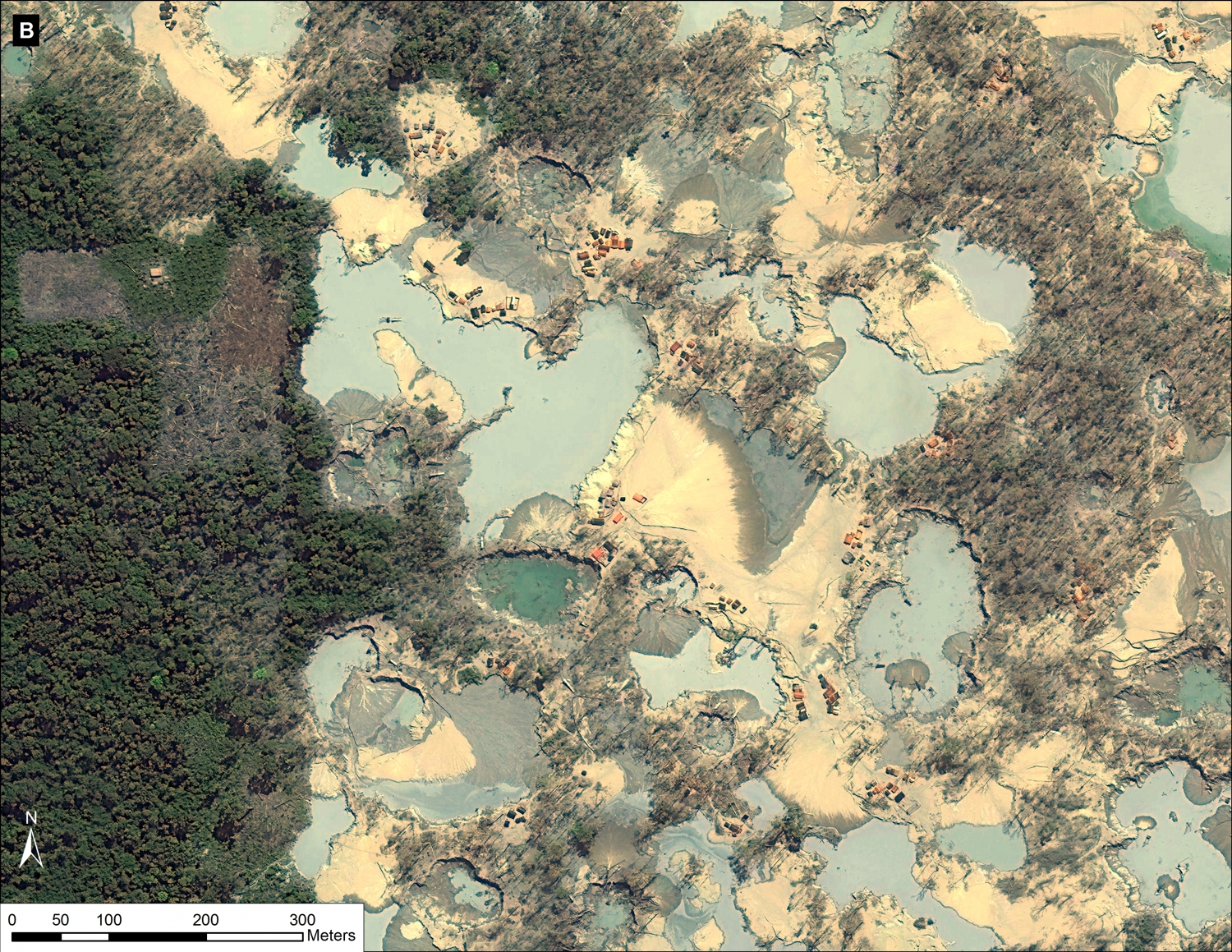

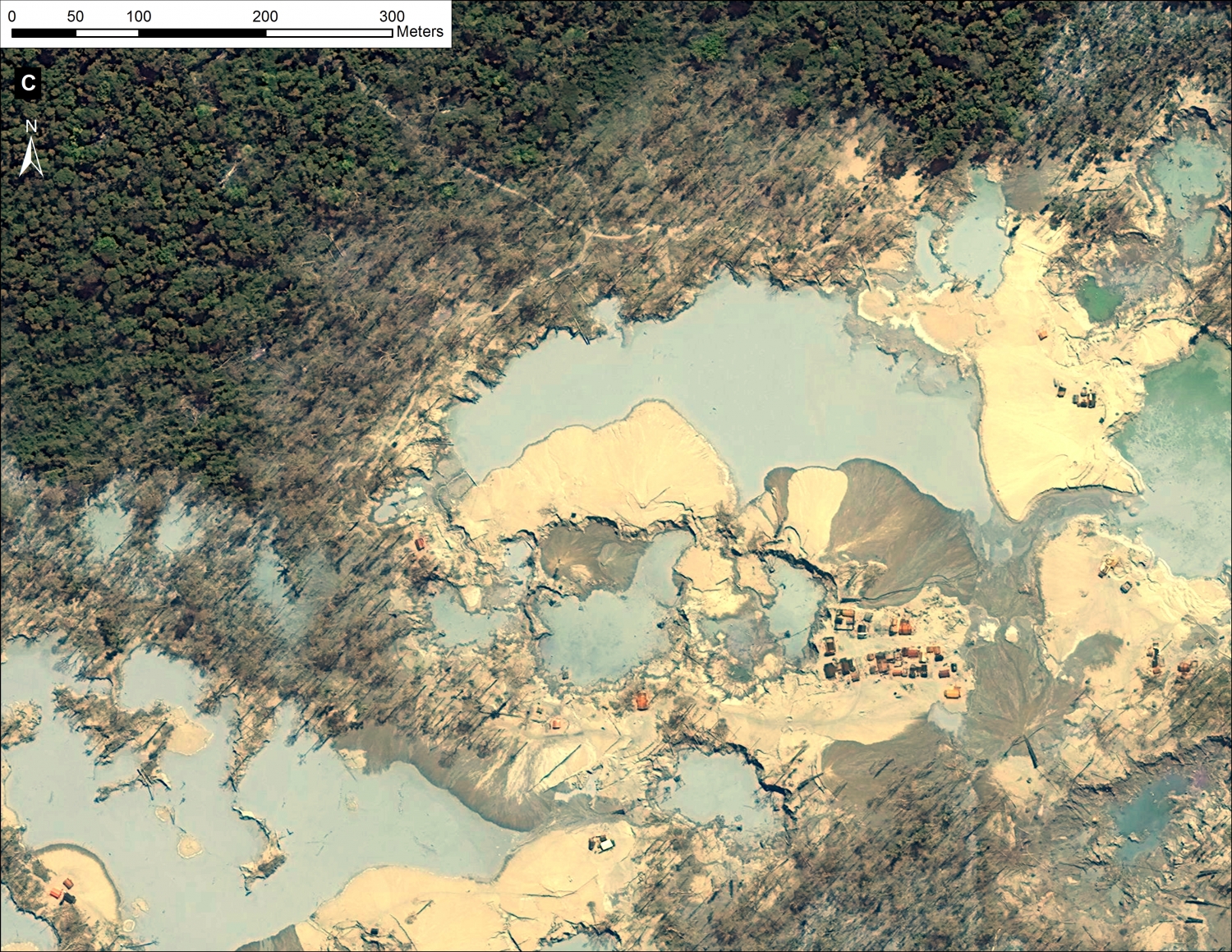

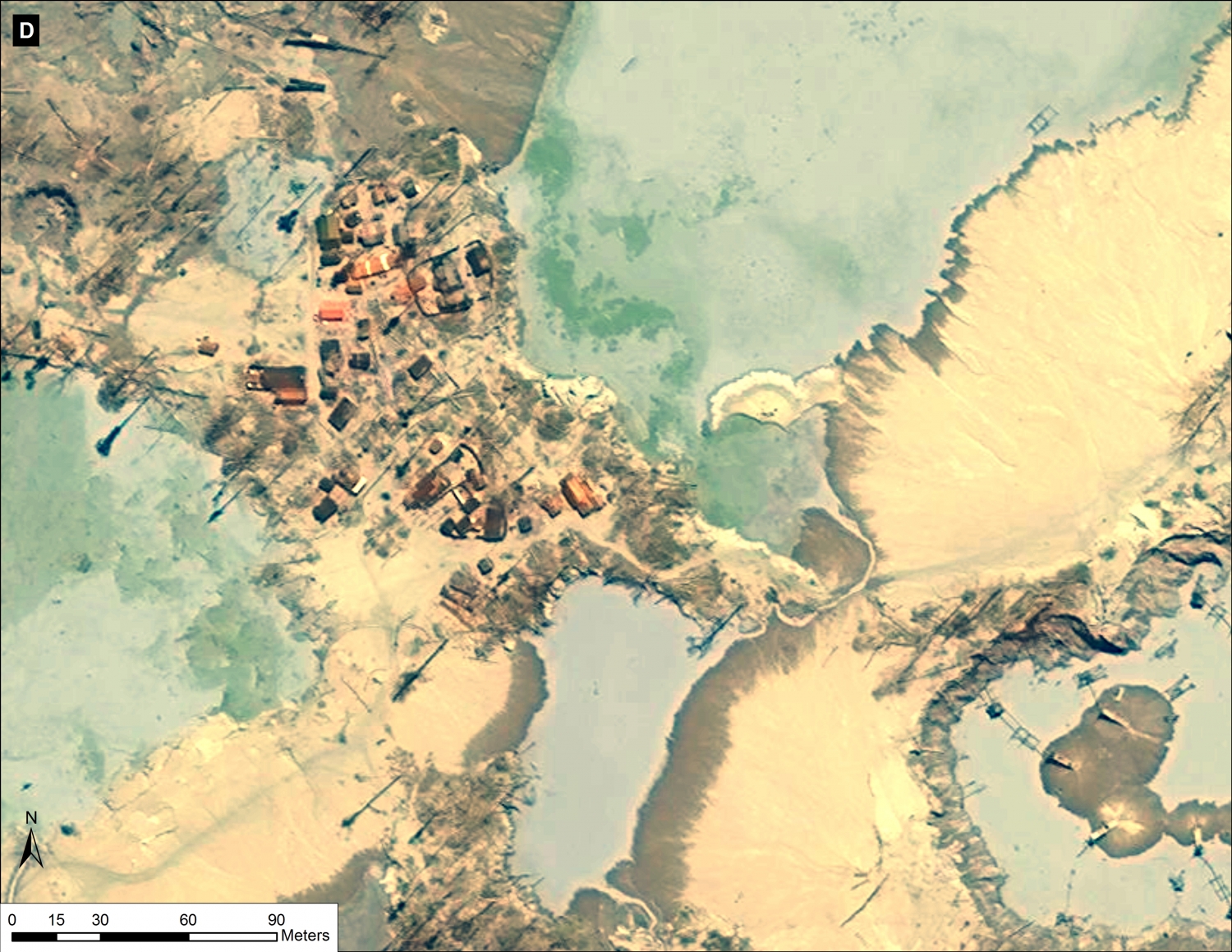

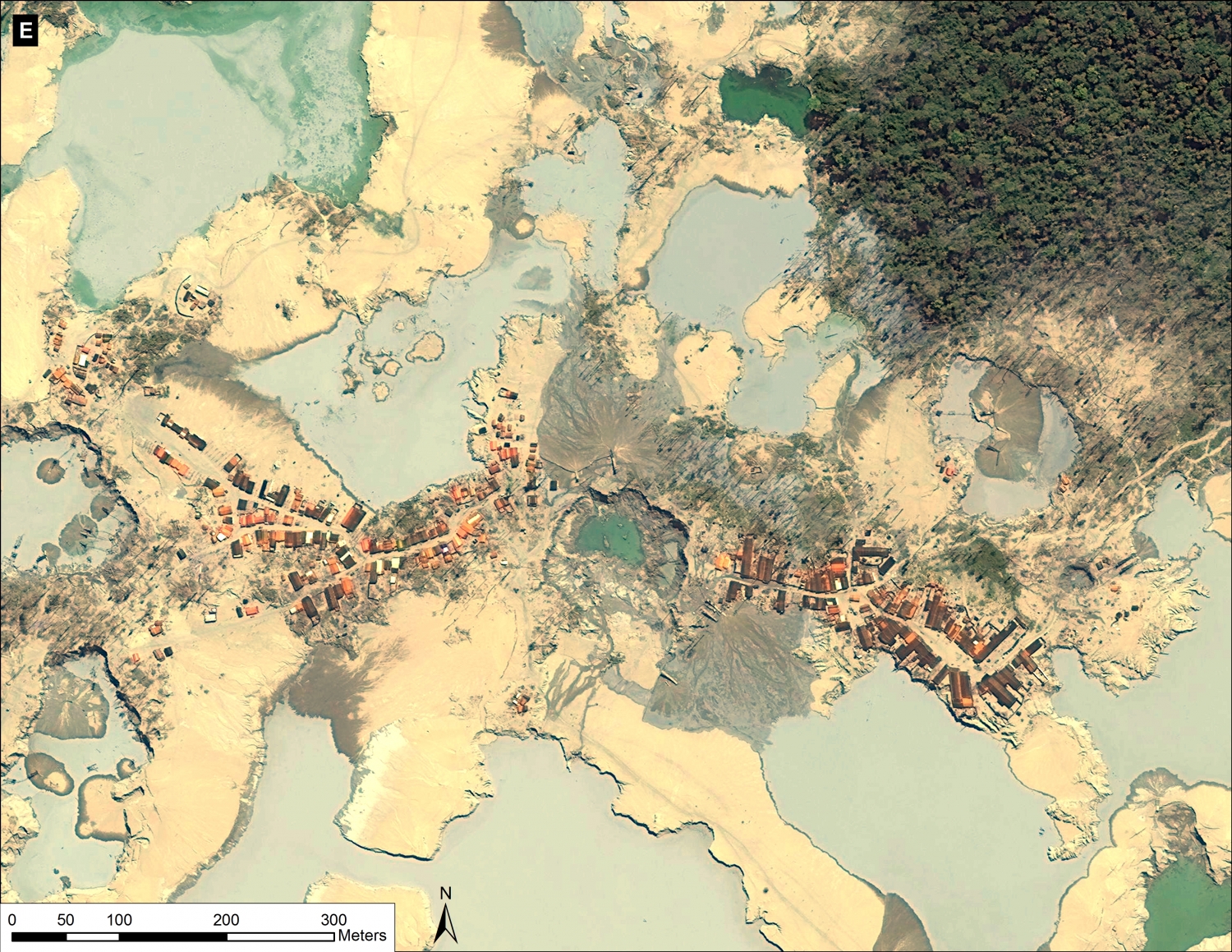

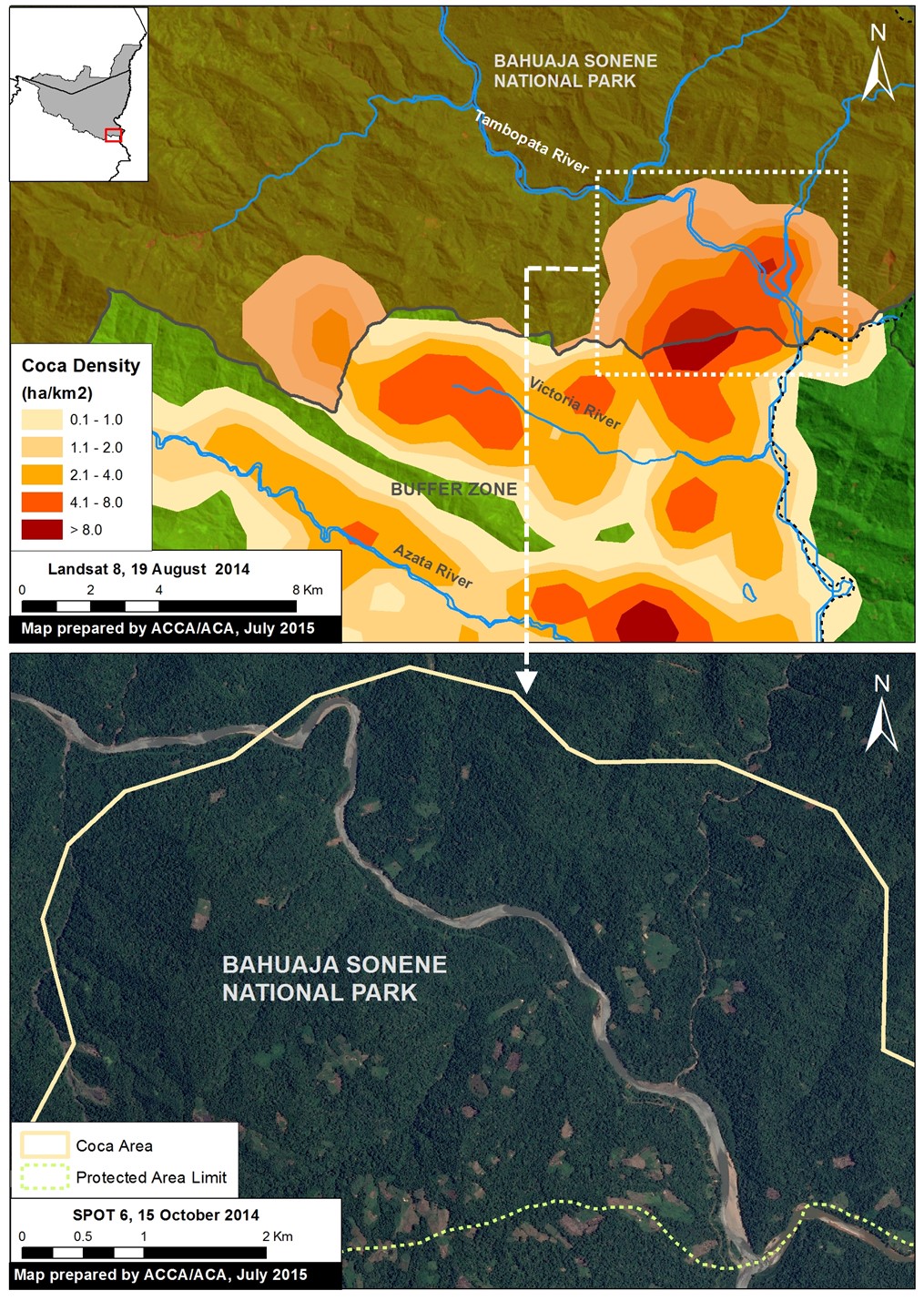

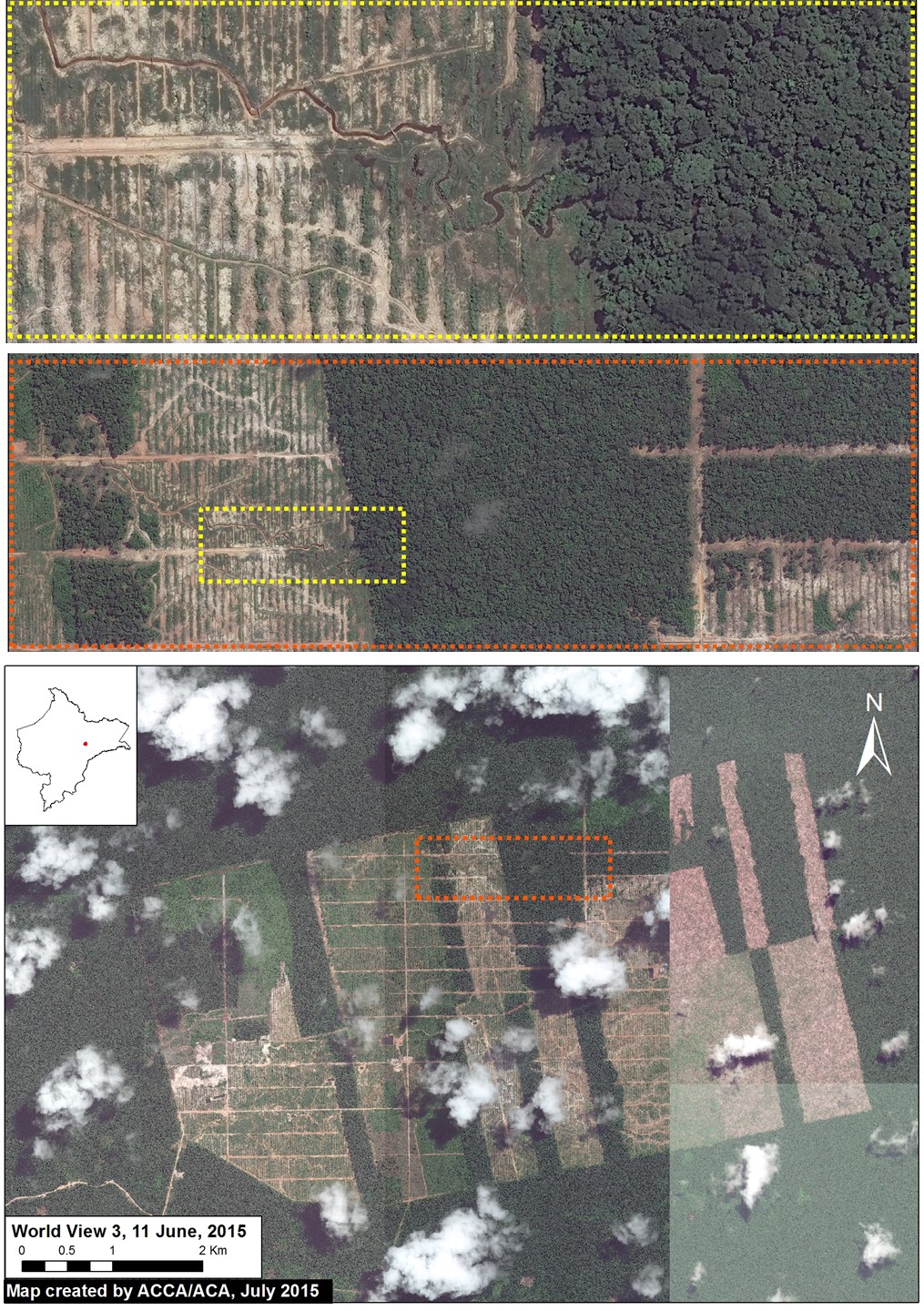

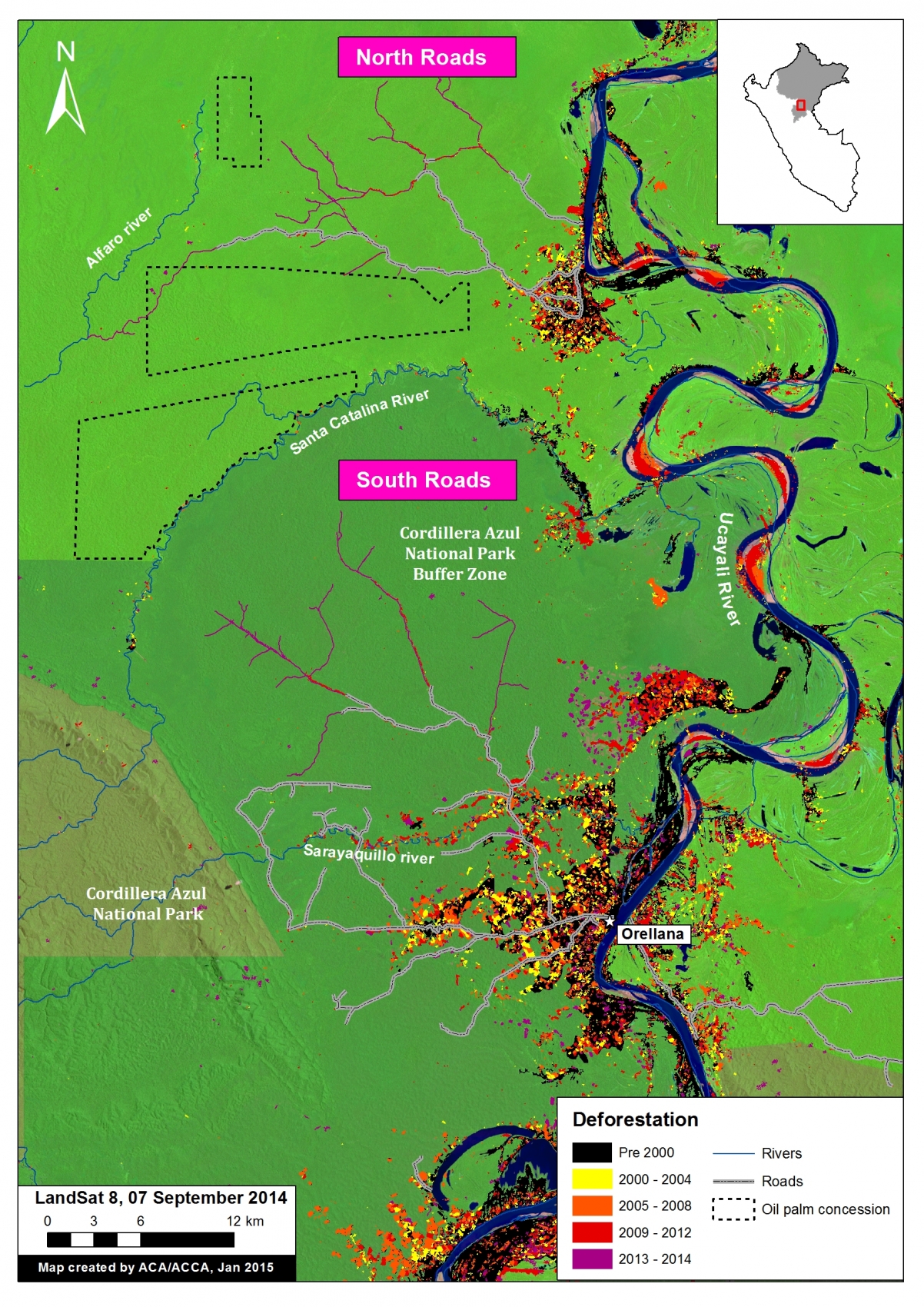

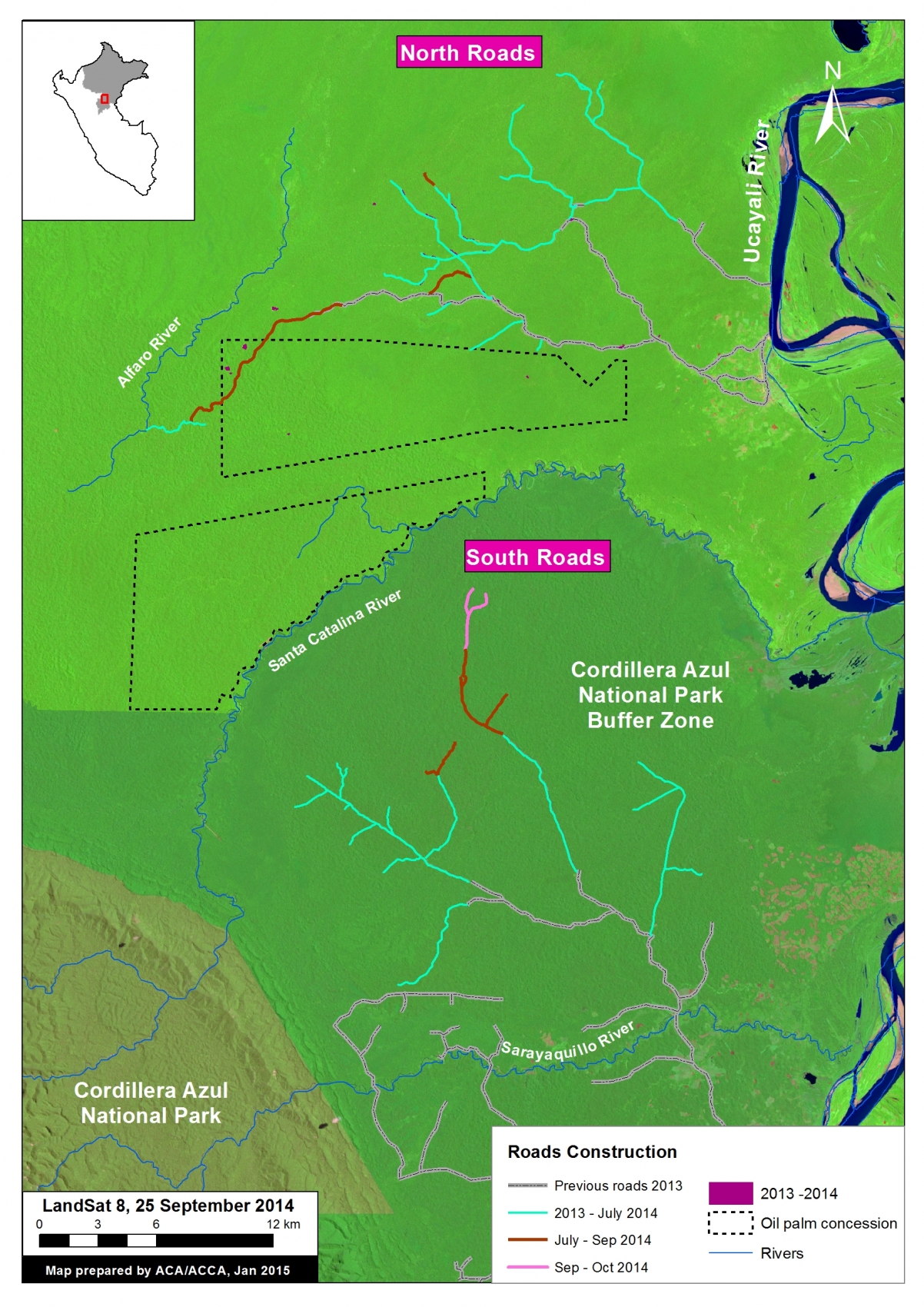

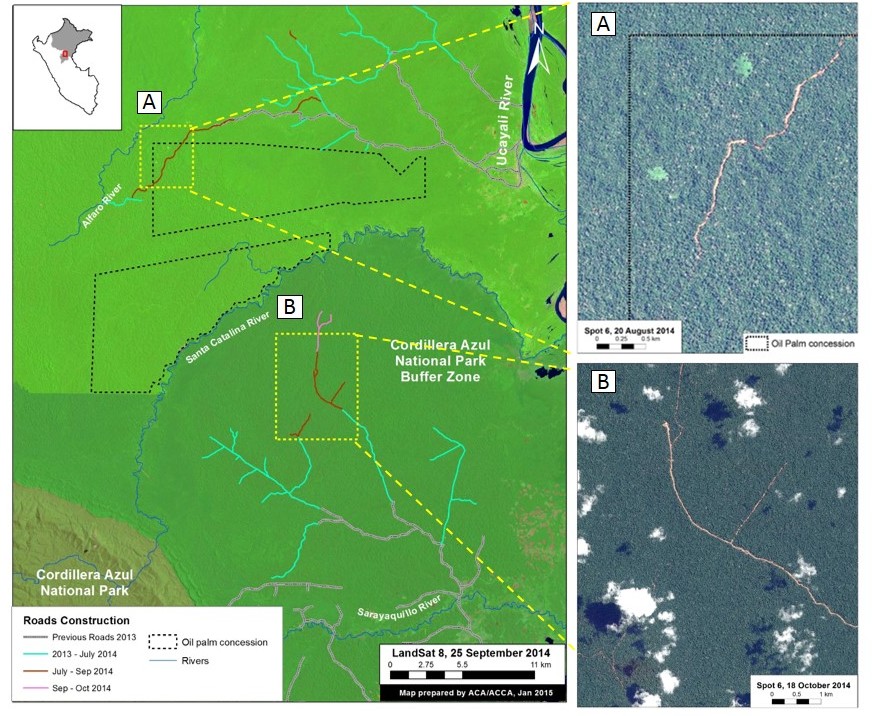

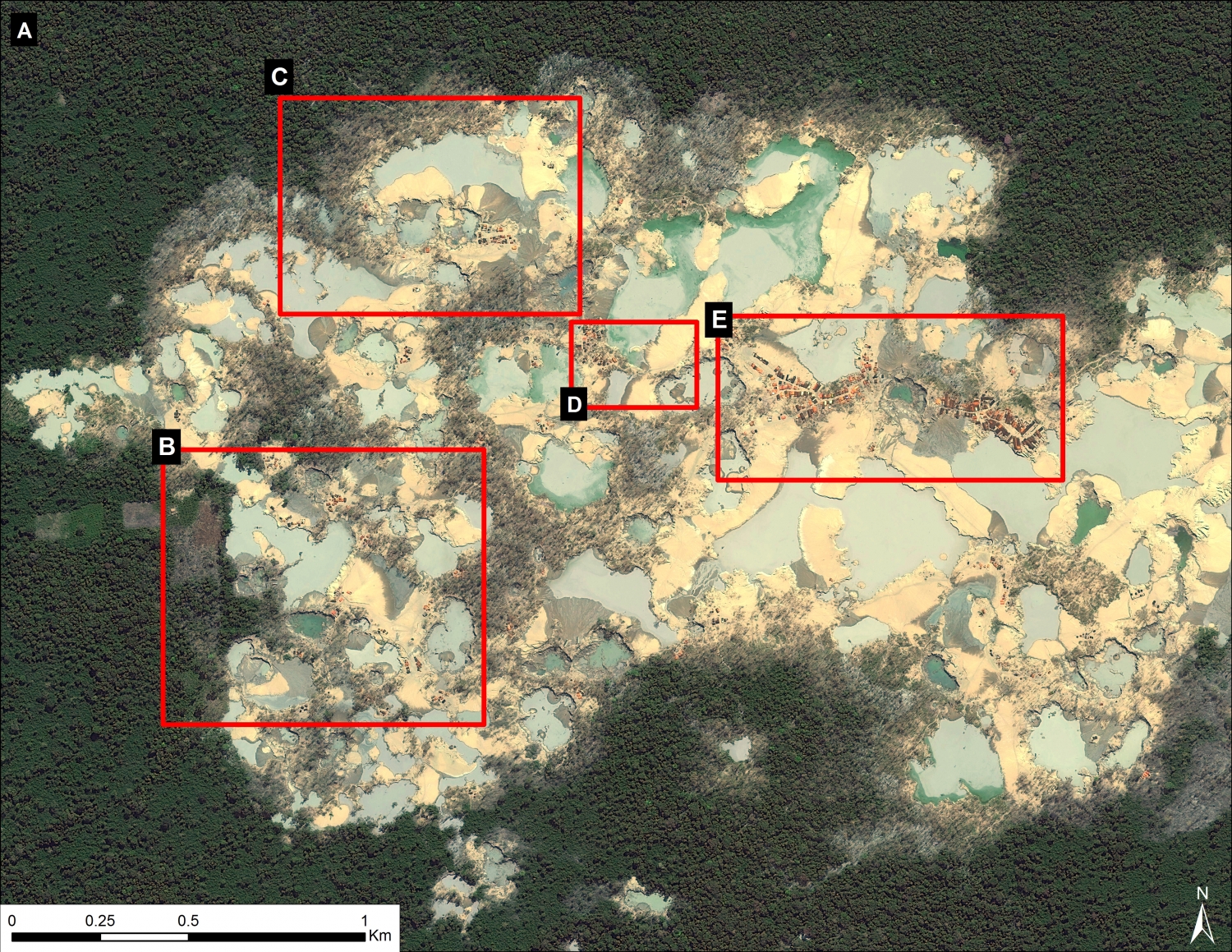

This series of maps illustrates the scale and magnitude of gold mining operations in La Pampa as of July 29, 2015, just two weeks after a major raid by the Peruvian government against illegal gold mining camps.

Image 12c displays, in high-resolution, the current center of the mining activity in La Pampa. Note that it is a zoom of zone A indicated in Image 12a. One can see the high density of gold mining operations and infrastructure in almost every area of the image. Also note in Image 12c that the location of four additional zooms described below are also shown.

Images 12d – g show a series of additional zooms from four different locations within the center of the current mining activity in this sector of La Pampa and highlights the scale and magnitude of operations.

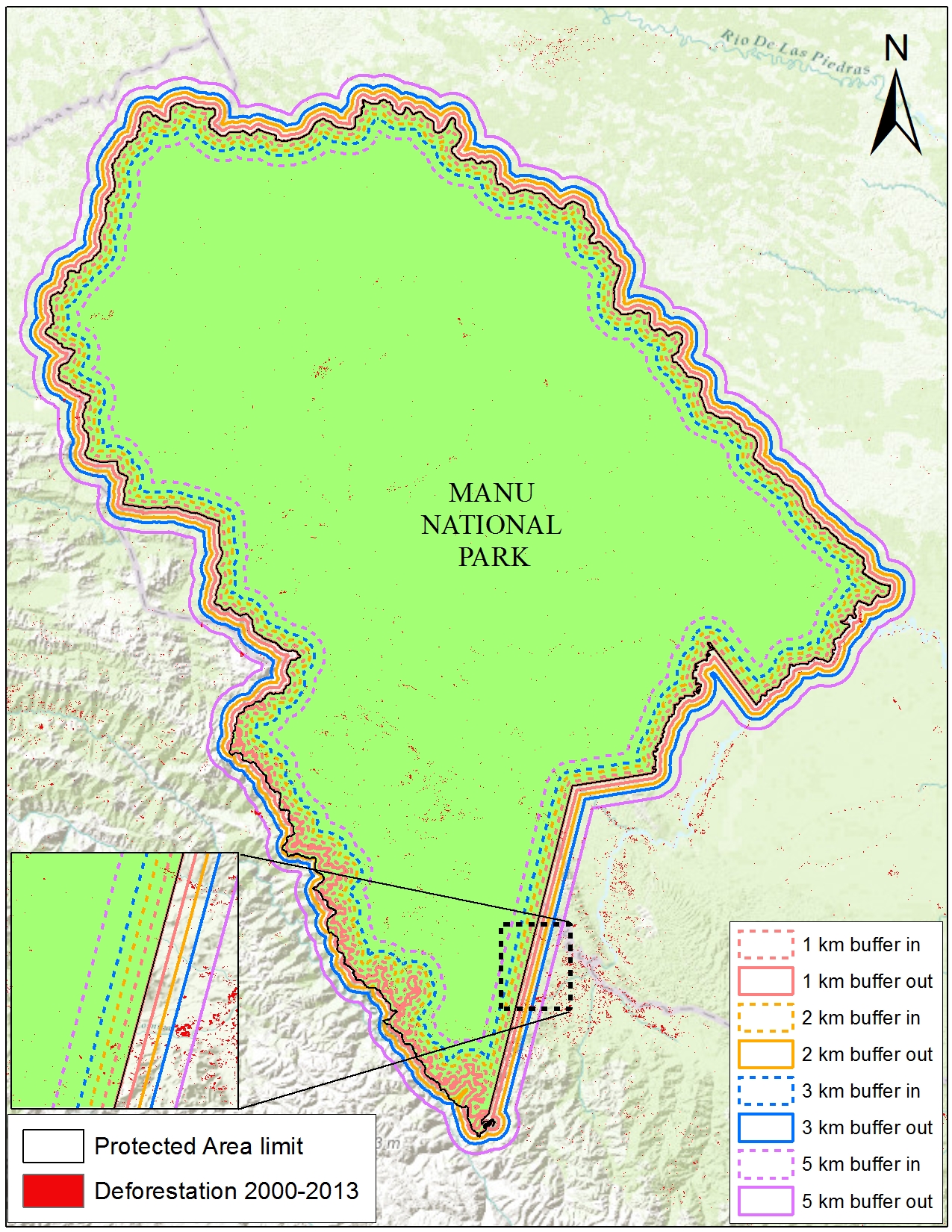

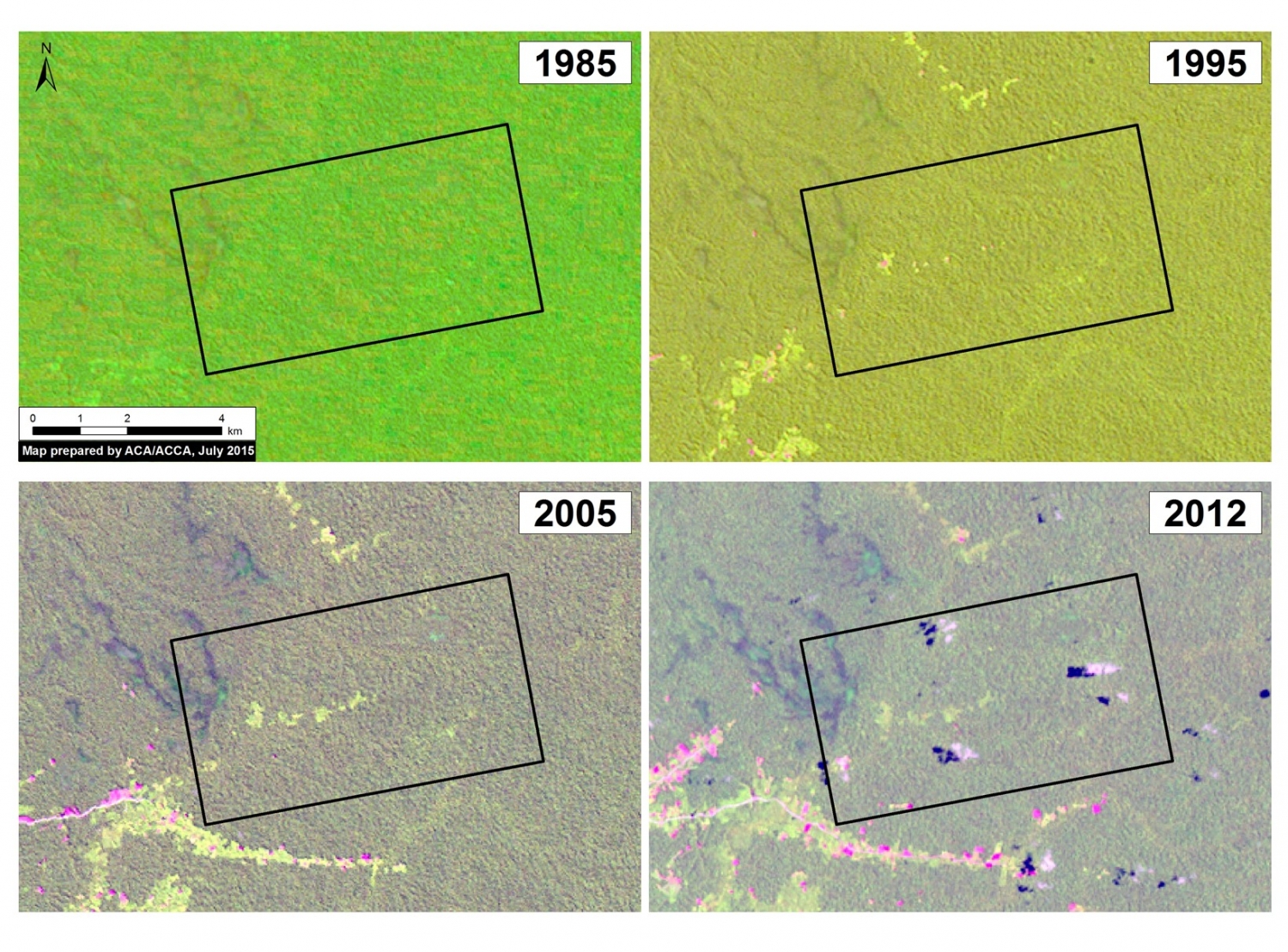

Tambopata National Reserve: Defense Against Deforestation

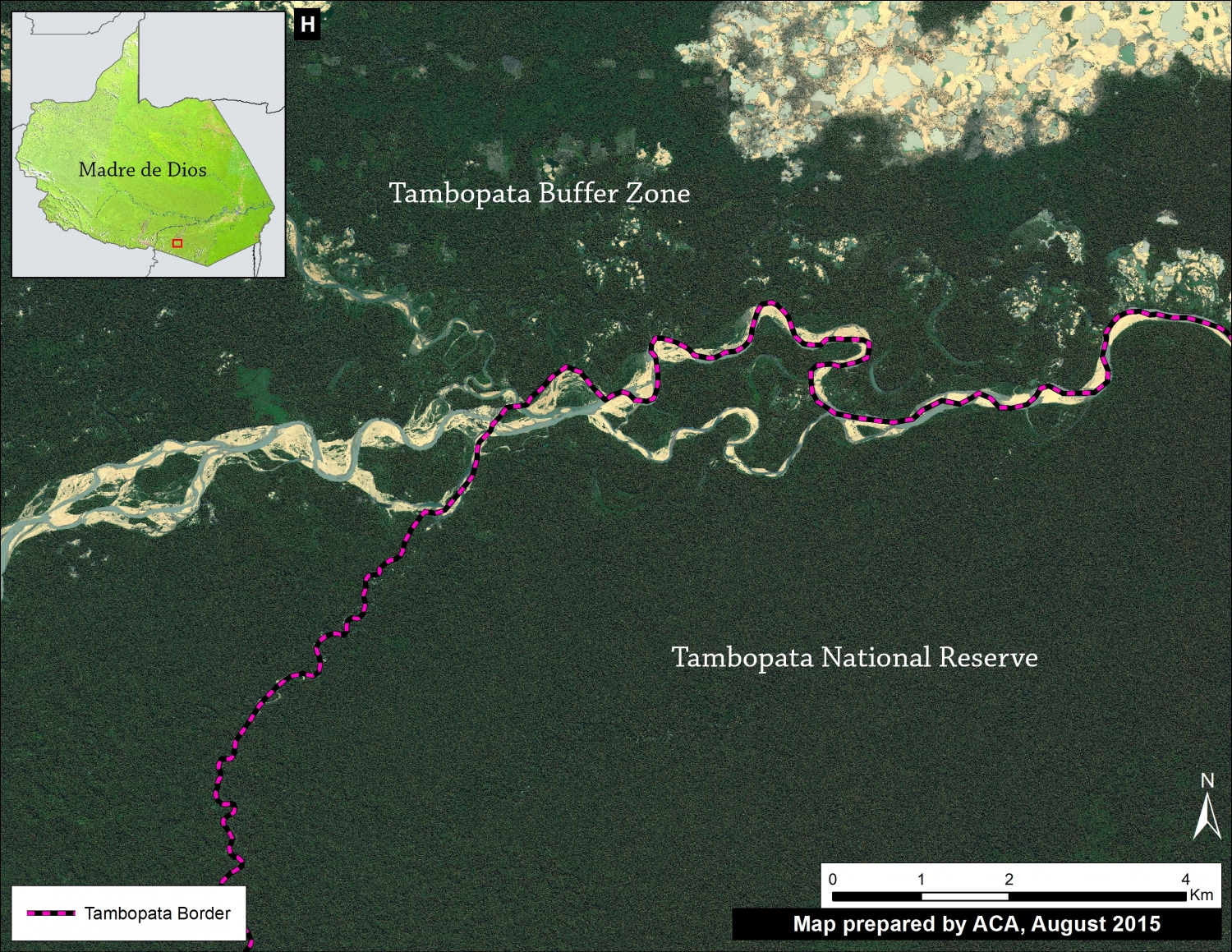

Image 12h illustrates how the Tambopata National Reserve remains a good defense against deforestation.

SERNANP Response

In response to this article, SERNANP (the Peruvian protected areas agency) issued this statement:

The area known as La Pampa is located in the buffer zone of the Tambopata National Reserve (RNTAMB) in the Madre de Dios region.

“El sector denominado La Pampa se encuentra ubicado en la zona de amortiguamiento de la Reserva Nacional Tambopata (RNTAMB) en la región Madre de Dios.”

In its capacity as lead agency of natural protected areas of Peru, SERNANP has been making great efforts to deal with illegal mining and other activities that threaten the Reserve. As part of these actions, we carried out monitoring in this region through images from LANDSAT 8). This monitoring system has confirmed the excellent state of conservation of the Reserve. Information has also been collected by park guards on patrols conducted along the Malinowski River and on monitoring trails located within the protected area.

“En su calidad de ente rector de las áreas naturales protegidas del Perú, el SERNANP viene realizando grandes esfuerzos para hacer frente a la minería ilegal y otras actividades que amenacen a la Reserva. Como parte de estas acciones se realiza un monitoreo mediante imágenes (LANSAT 8), sistema que ha corroborado el óptimo estado de conservación de la Reserva, información que ha sido recopilada también por los guardaparques en los patrullajes realizados a lo largo del río Malinowski y en las trochas de monitoreo ubicadas al interior del área protegida.”

Similarly, this system has allowed SERNANP to collect information on threats in the buffer zone, data that has been shared promptly with leading authorities on illegal mining. This information is centered on points of access to the buffer zone, trails, gas stations, distances, among others; this has contributed to the development and implementation of the strategy against illegal mining in the Tambopata Natural Reserve.

“Asimismo, este sistema ha permitido recopilar información sobre las amenazas en la zona de amortiguamiento, datos que han sido compartidos oportunamente con las principales autoridades competentes en materia de minería ilegal. Esta información está centrada en puntos de acceso a la zona de amortiguamiento, trochas, grifos, distancias, entre otros; lo que ha contribuido en la elaboración y aplicación de la estrategia de la RN Tambopata contra la minería ilegal.”

This strategy also includes the continued involvement and support of the Chief of the Tambopata National Reserve on issues related to the promotion of economic activities and the exploitation of natural resources by local populations, promoting tourism as a strategy for conservation of the protected area, lectures on environmental education, and others.

“Esta estrategia comprende también la permanente participación y apoyo de la Jefatura de la Reserva Nacional Tambopata en temas relacionados con el impulso de actividades económicas como el aprovechamiento de recursos naturales por parte de las poblaciones locales, la promoción del turismo como estrategia de conservación del área protegida, charlas de educación ambiental, entre otros.”

Citation

Finer M, Olexy T (2015) High Resolution View of Illegal Gold Mining in La Pampa (Madre de Dios, Peru). MAAP #12. Link: https://www.maapprogram.org/2015/08/image12-lapampa/