Intro Image. Amazon Mining Watch interactive map.

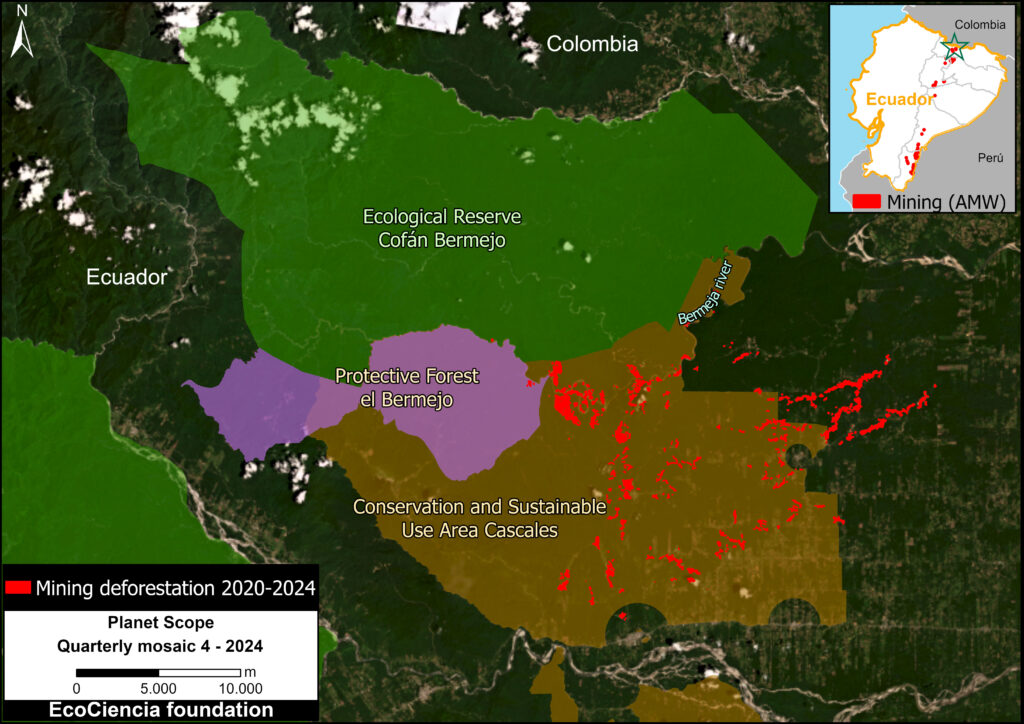

As gold prices continue to increase, small-scale gold mining activity also continues to be one of the major deforestation drivers across the Amazon.

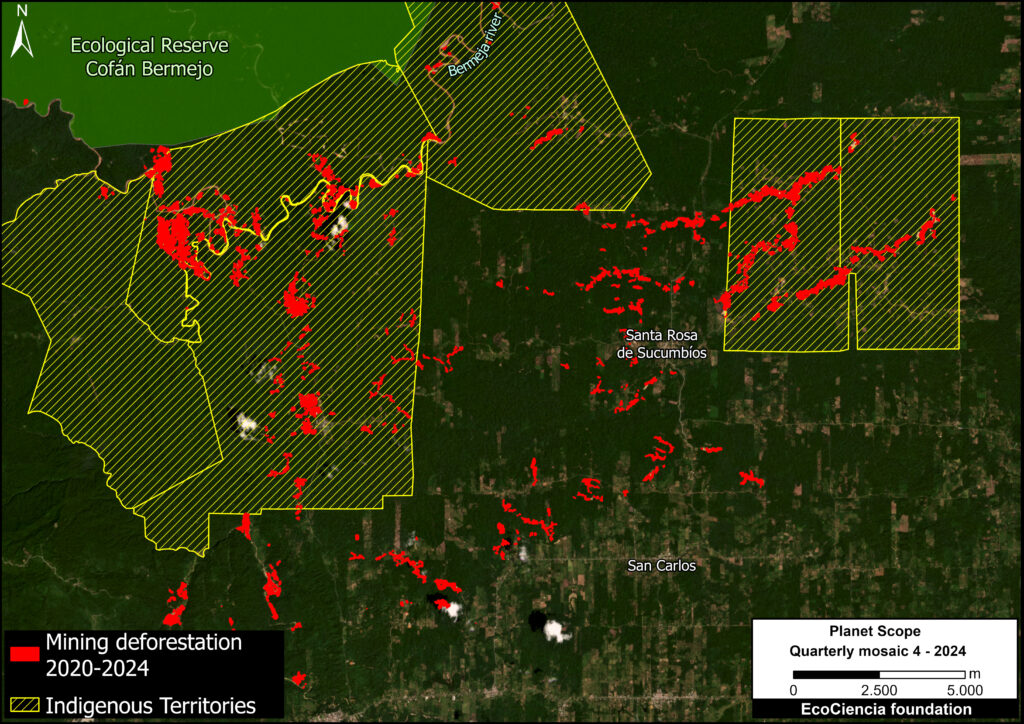

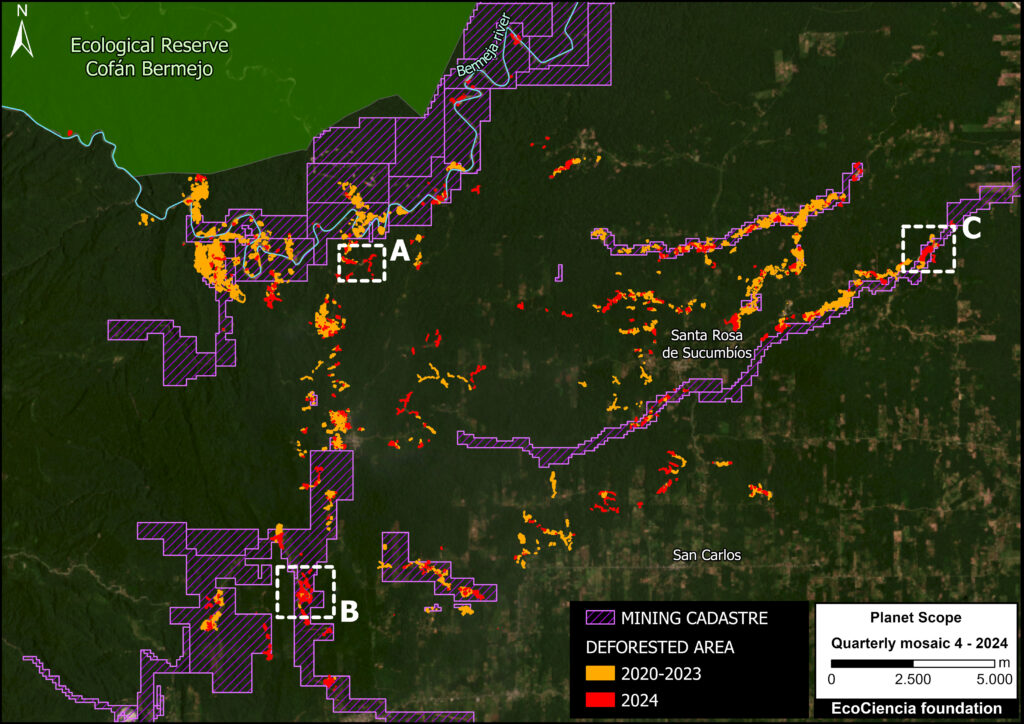

It often targets remote areas, thus impacting carbon-rich primary forests. Moreover, in many cases, we presume that this mining is illegal based on its location within conservation areas (such as protected areas and Indigenous territories) and outside mining concessions.

Given the vastness of the Amazon, however, it has been a challenge to accurately and regularly monitor mining deforestation across all nine countries of the biome, in order to better inform related policies in a timely manner.

In a previous report (MAAP #212) we presented the initial results of the new AI-based dashboard (known as Amazon Mining Watch) designed to address the issue of gold mining and related policy implications. Amazon Mining Watch (AMW) is a partnership between Earth Genome, the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network, and Amazon Conservation.

This online tool (see Intro Image) analyzes satellite imagery archives to estimate annual mining deforestation footprints across the entire Amazon, from 2018 to 2024 (Note 1). Although the data is not designed for precise area measurements, it can be used to give timely estimates needed for management and conservation purposes.

For example, the cumulative data can be used to estimate and visualize the overall Amazon-wide mining deforestation footprint, and the annual data can be used to identify trends and emerging new mining areas. The algorithm is based on 10-meter resolution imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellite and produces 480-meter resolution pixelated mining deforestation alerts.

The only tool of this kind to be truly regional (Amazon-wide) in coverage, AMW can also help foster regional cooperation, in particular in transfrontier areas where a lack of interoperability between official monitoring systems might hamper interventions.

The Amazon Mining Watch partnership is currently working to enhance the functionality and conservation impact of the dashboard, AMW will be a one-stop shop platform including real-time visualization of: 1) AI-based detection of mining deforestation across all nine Amazonian countries, with quarterly updates; 2) Hotspots of urgent mining cases, including river-based mining; and 3) the socio-environmental costs of illegal gold mining with the Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF) Mining Impacts Calculator.

Here, we present an update focused on the newly added 2024 data and its context within the cumulative dataset (since 2018).

MAJOR FINDINGS

In the following sections, we highlight several major findings:

- Gold mining is actively causing deforestation in all nine countries of the Amazon. This impact is concentrated in three major areas: southeast Brazil, the Guyana Shield, and southern Peru. In addition, mining in Ecuador is escalating.

- The cumulative mining deforestation footprint in 2024 was over 2 million hectares (nearly 5 million acres) and has increased by over 50% in the past six years.

- Over half of all Amazon mining deforestation occurred in Brazil, followed by Guyana, Suriname, Venezuela, and Peru.

- While the cumulative footprint continues to grow, the rate of increase slowed in 2023 and 2024 after peaking in 2022, likely due to increased enforcement in Brazil.

- Over one-third of the mining deforestation has occurred within protected areas and Indigenous territories, where much of it is likely illegal. We highlight the most impacted areas.

- These results have important policy implications.

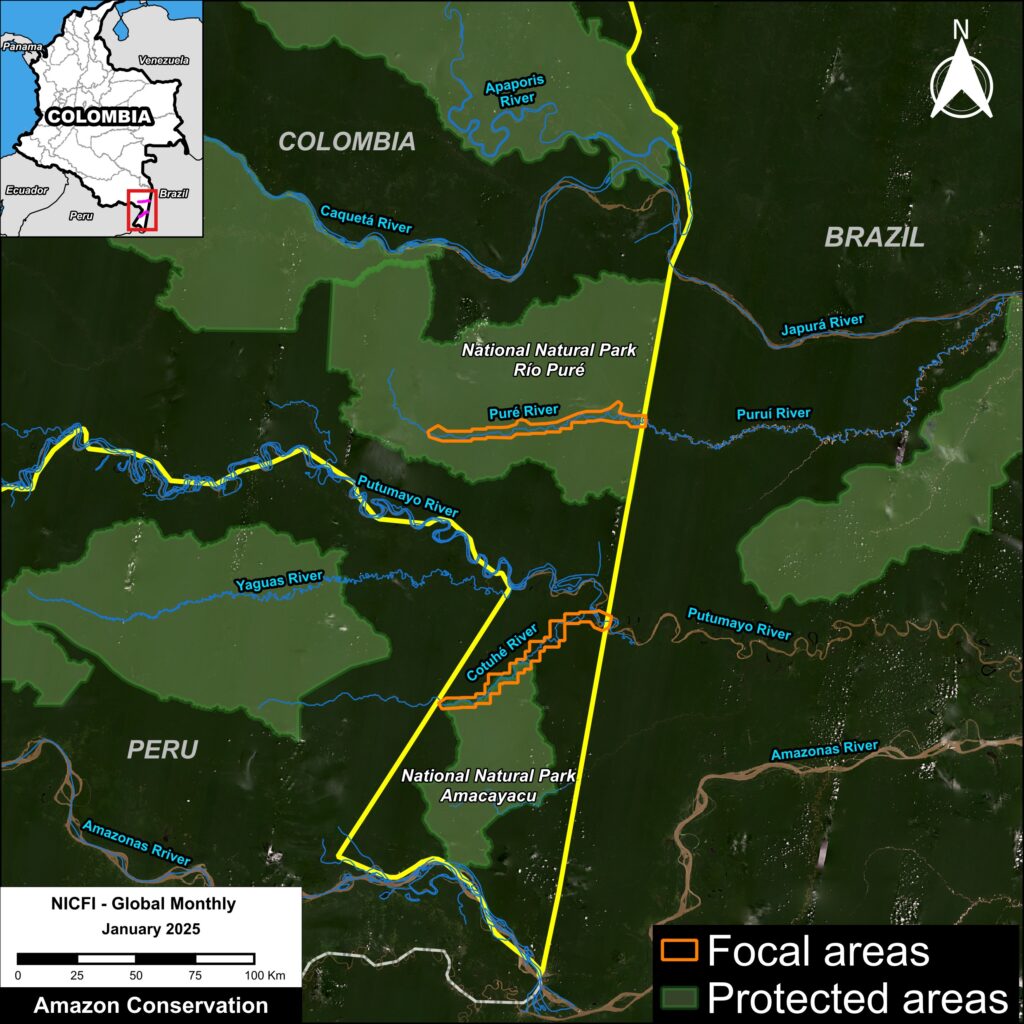

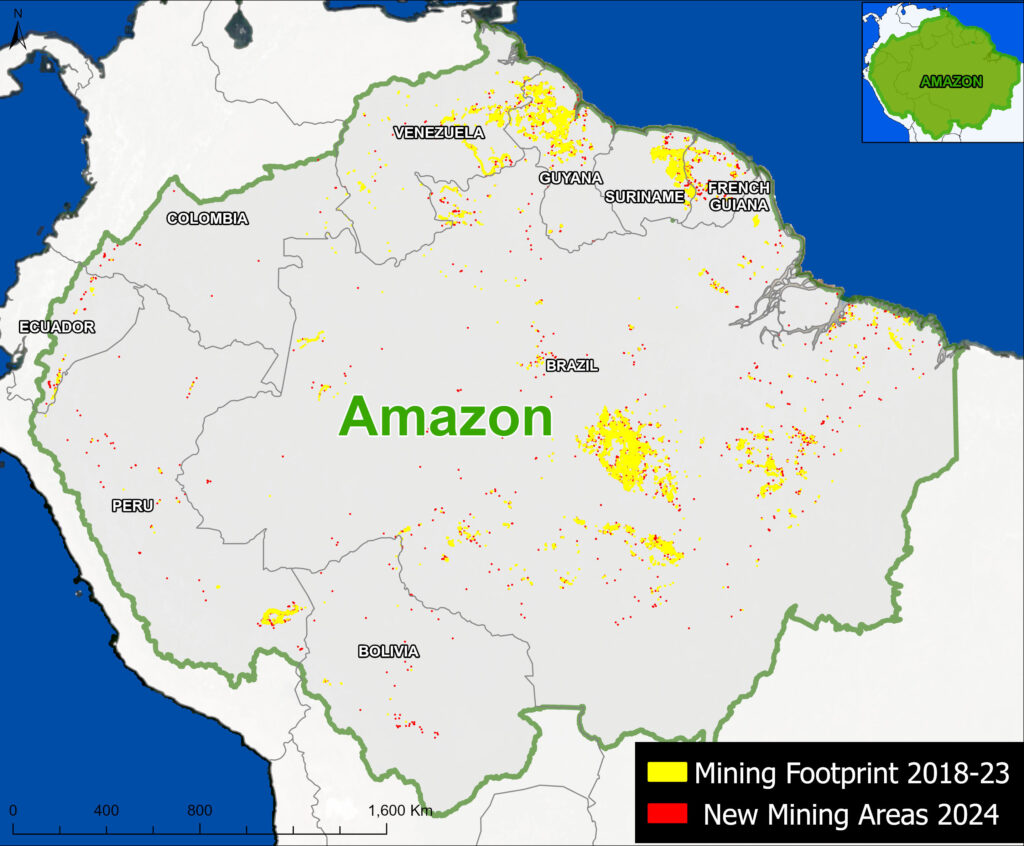

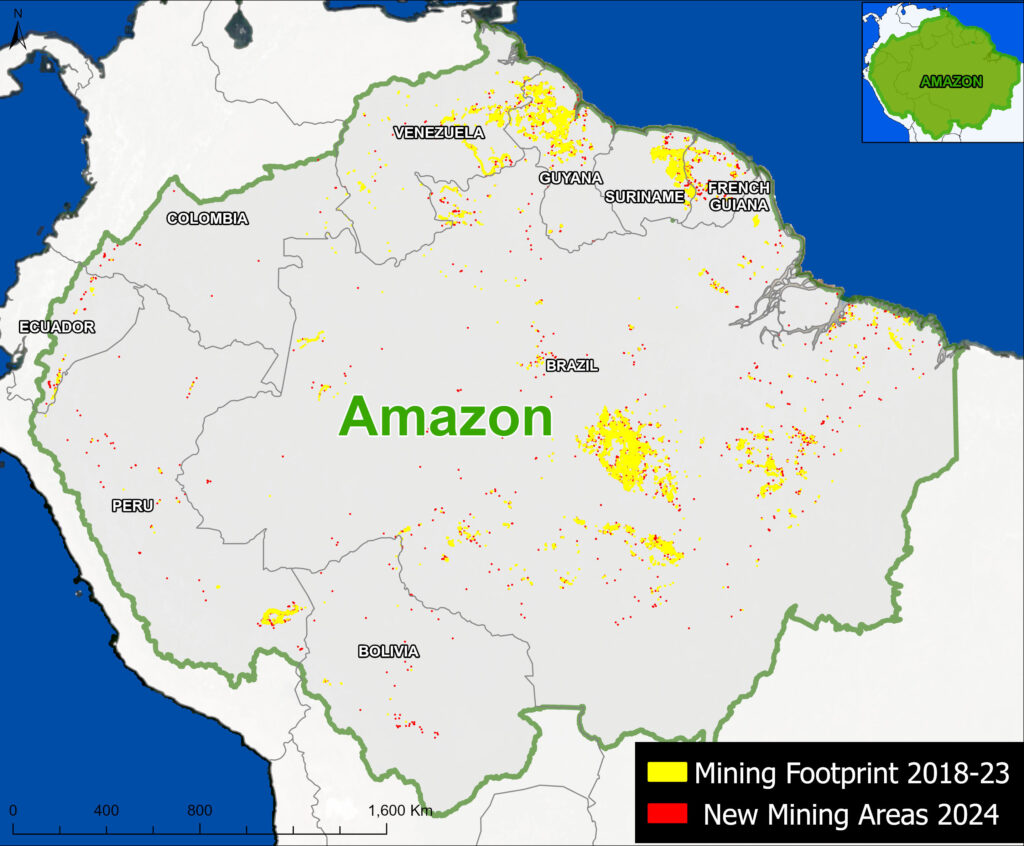

Base Map. Mining deforestation footprints, 2018-2024. Data: AMW, Amazon Conservation/MAAP.

Amazon & National Scale Patterns

The Base Map presents the gold mining footprint across the Amazon, as detected by the AMW algorithm. This data serves as our estimate of gold mining deforestation.

Yellow indicates the accumulated mining deforestation footprint for the years 2018- 2023; that is, all areas that the algorithm classified as a mining site vs other types of terrain, such as forest or agriculture. Red indicates the new mining areas detected in 2024.

Three major Amazon gold mining regions stand out: southeast Brazil (between the Tapajos, Xingu, and Tocantis Rivers), Guyana Shield (Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname, and French Guiana), and southern Peru (Madre de Dios). In addition, Ecuador has emerged as an important mining deforestation front.

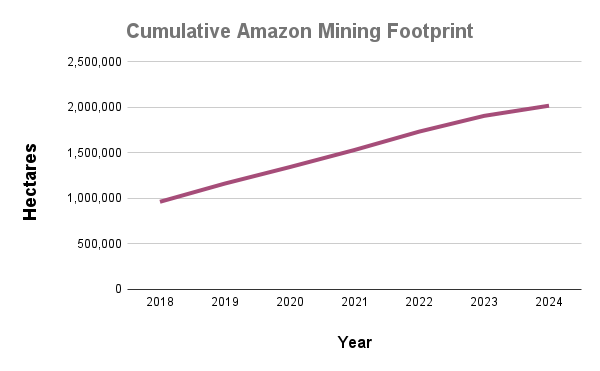

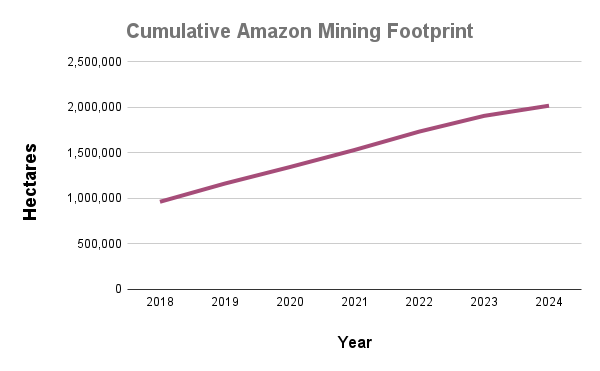

Graph 1. Amazon mining deforestation footprint. Data: AMW

Graph 1 quantifies the spatial data detected by the AMW algorithm.

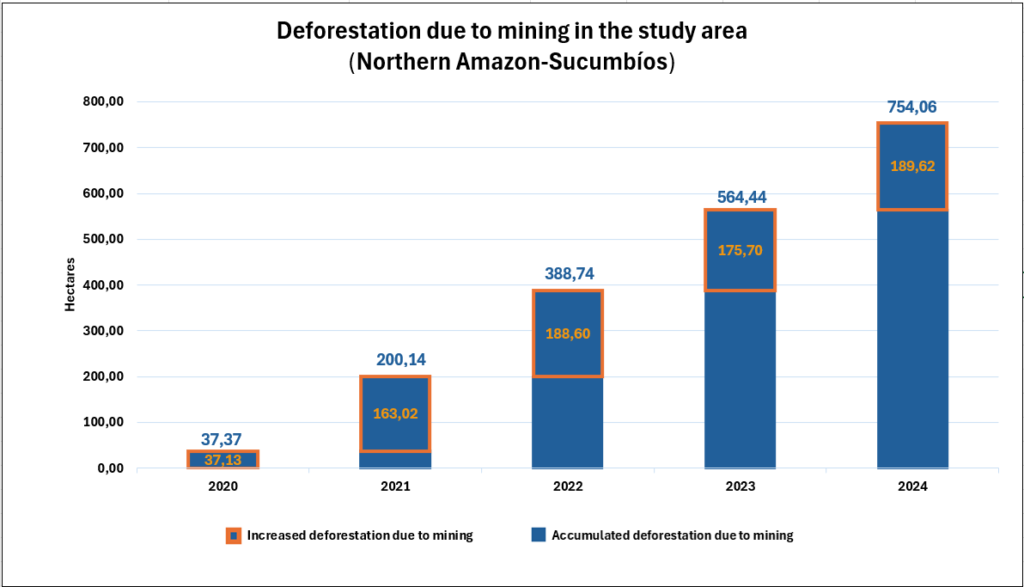

The cumulative mining deforestation footprint in 2024 was 2.02 million hectares (4.99 million acres)

For context, the initial mining deforestation footprint was around 970,000 hectares in 2018, the first year of Amazon Mining Watch data.

Between 2019 and 2024, we estimate that the gold mining deforestation grew by 1.06 million hectares (2.61 million acres).

Thus, over half (52.3%) of the cumulative footprint has occurred in just the past six years.

Note that while the cumulative footprint continues to grow, the rate of increase slowed in 2023 and 2024 after peaking in 2022.

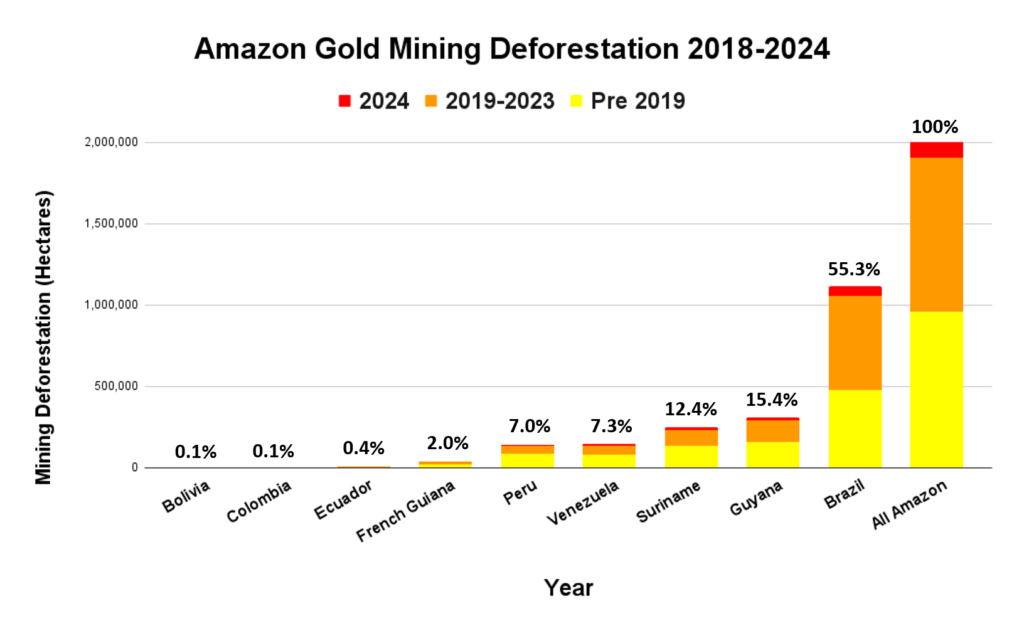

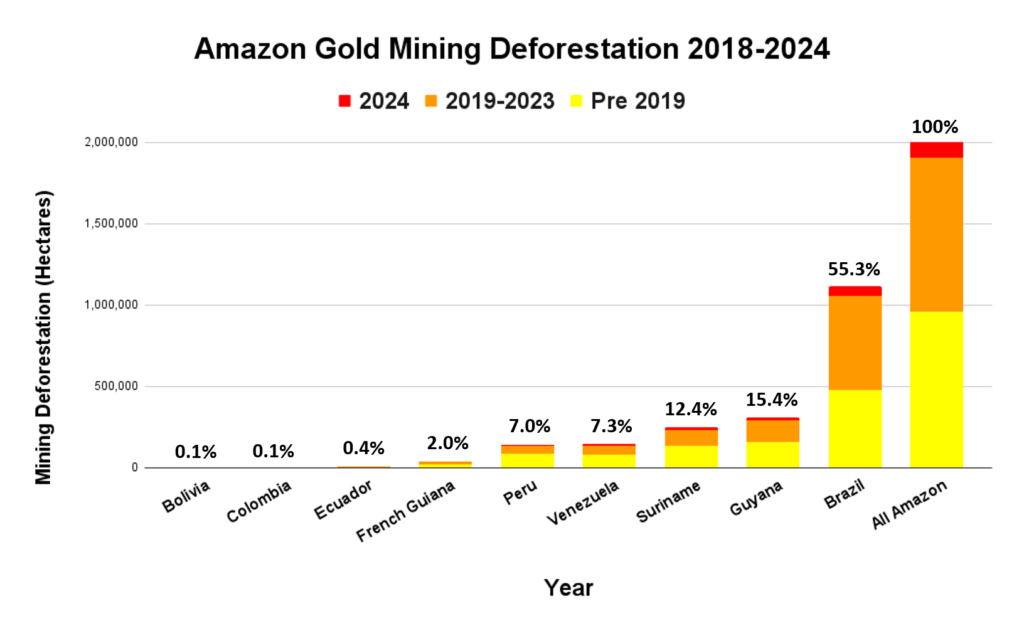

Graph 2 shows that, of the total accumulated mining (2.02 million hectares), over half has occurred in Brazil (55.3%), followed by Guyana (15.4%), Suriname (12.4%), Venezuela (7.3%), and Peru (7.0%).

Graph 2. Gold mining deforestation across the Amazon, by country. Data: AMW, Amazon Conservation/MAAP

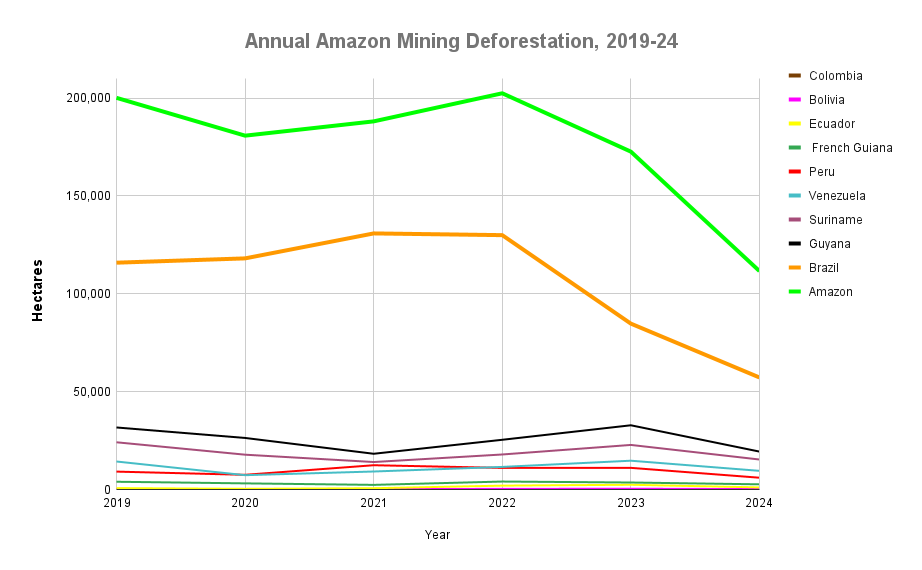

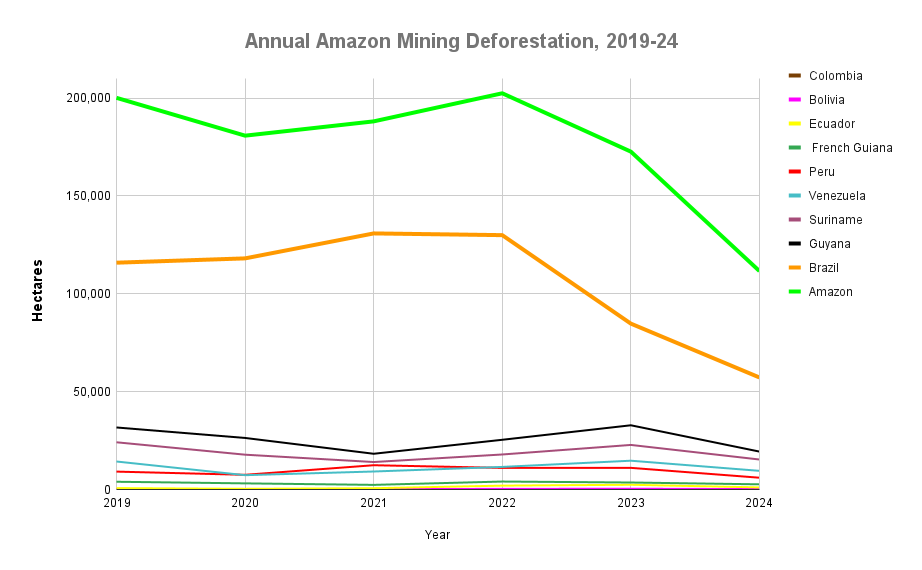

Graph 3 digs deeper into the AMW data, revealing additional trends between years. This data highlights the annual changes in detected mining deforestation. Note the trend across the entire Amazon at the top in green for overall context, followed by each country. Note that Brazil (orange line) accounts for much of the annual mining (over 50%).

In 2024, we documented the new gold mining deforestation of 111,603 hectares (275,777 acres). This total represents a decrease of 35% relative to the previous year 2023 and 45% relative to the peak year 2022.

The countries with the highest levels of new gold mining deforestation in 2024 were 1) Brazil (57,240 ha), 2) Guyana (19,372 ha), 3) Suriname (15,323 ha), 4) Venezuela (9,531 ha), and 5) Peru (6,020 ha). However, all five of these countries saw a major decrease in 2024, between 33% (Brazil and Suriname) and 46% (Peru).

Graph 3. Annual changes in new mining deforestation. Data: AMW

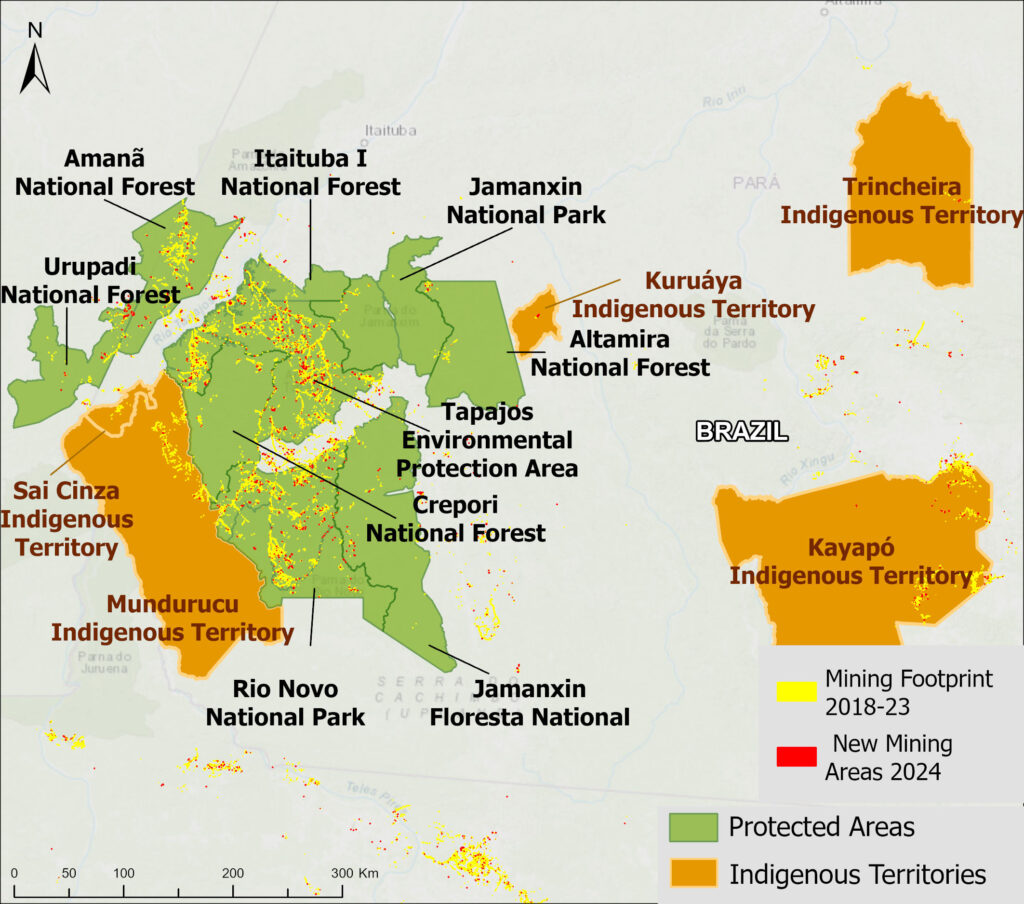

Figure 1. Protected areas & Indigenous territories impacted by mining deforestation. Data: AMW, ACA/MAAP.

Protected Areas & Indigenous Territories

We estimate that 36% of the accumulated mining deforestation in 2024 (over 725,000 hectares) occurred within protected areas and Indigenous territories (Figure 1; Note 2), where much of it is likely illegal.

Notably, the vast majority of this overall mining deforestation in protected areas and Indigenous territories has occurred in Brazil (88%).

Figure 2a. Top 10 impacted protected areas & Indigenous territories. Data: AMW, ACA/MAAP.

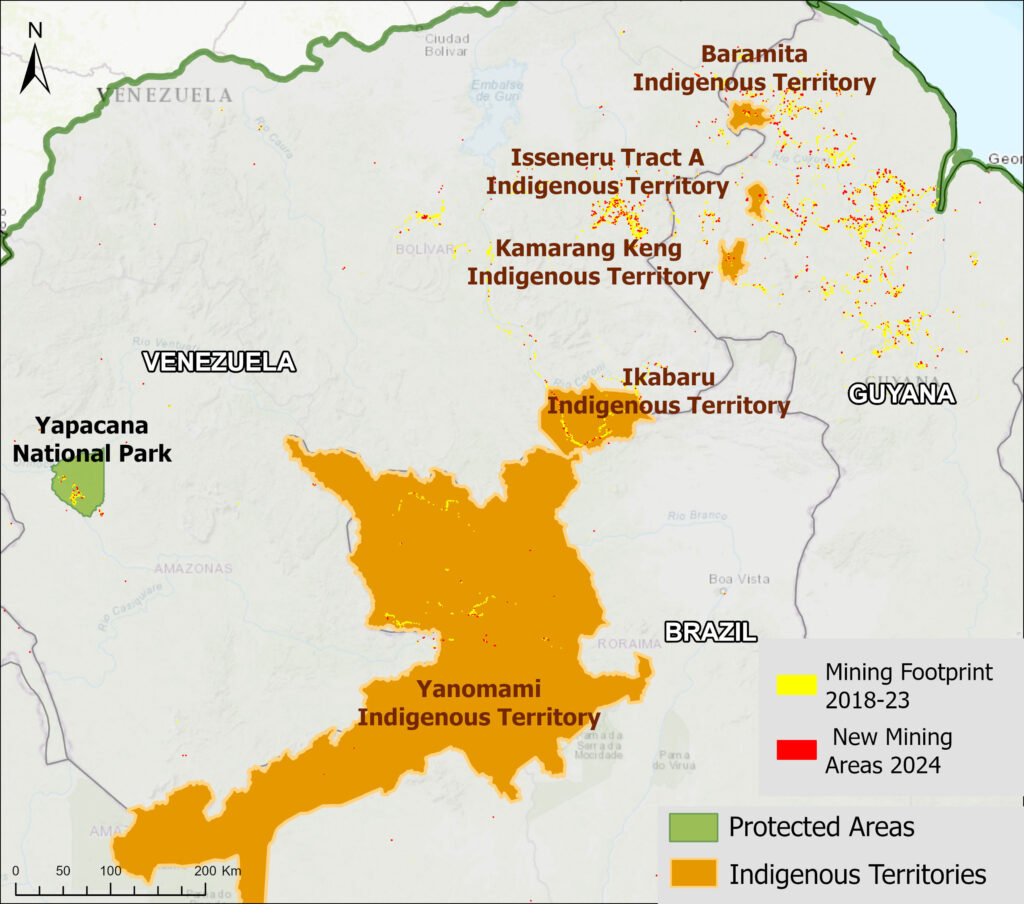

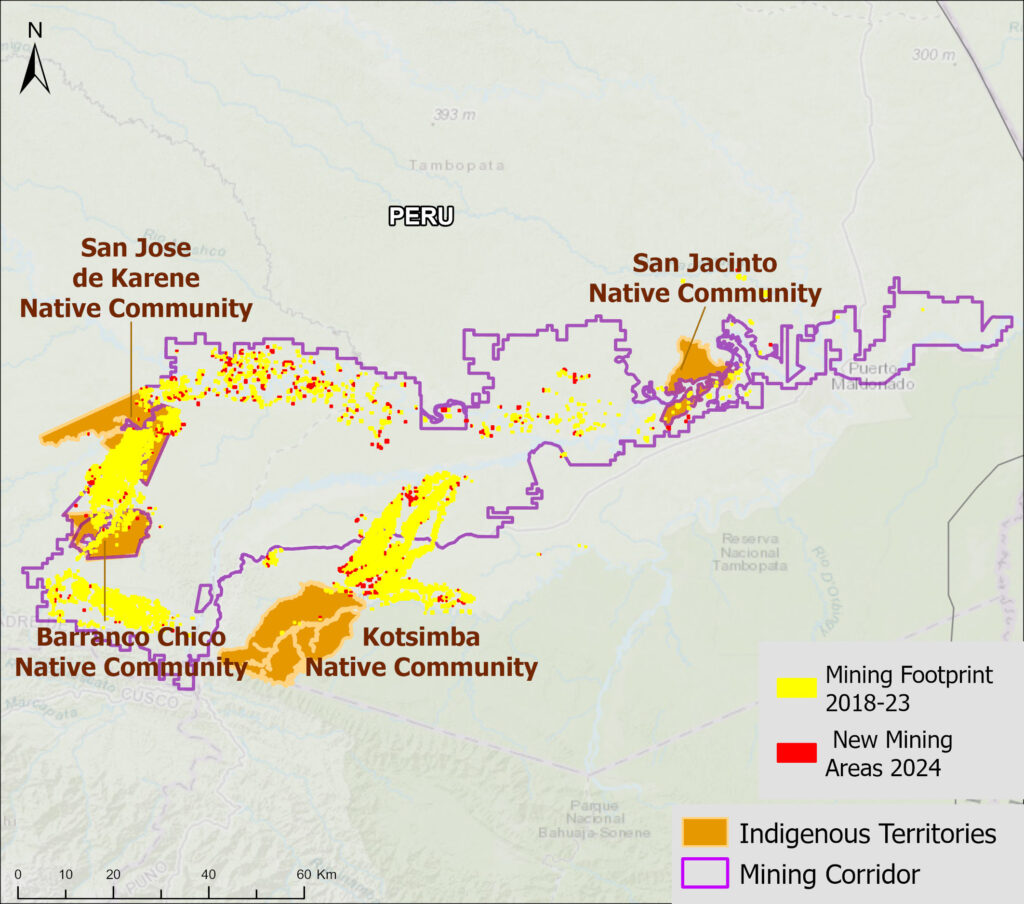

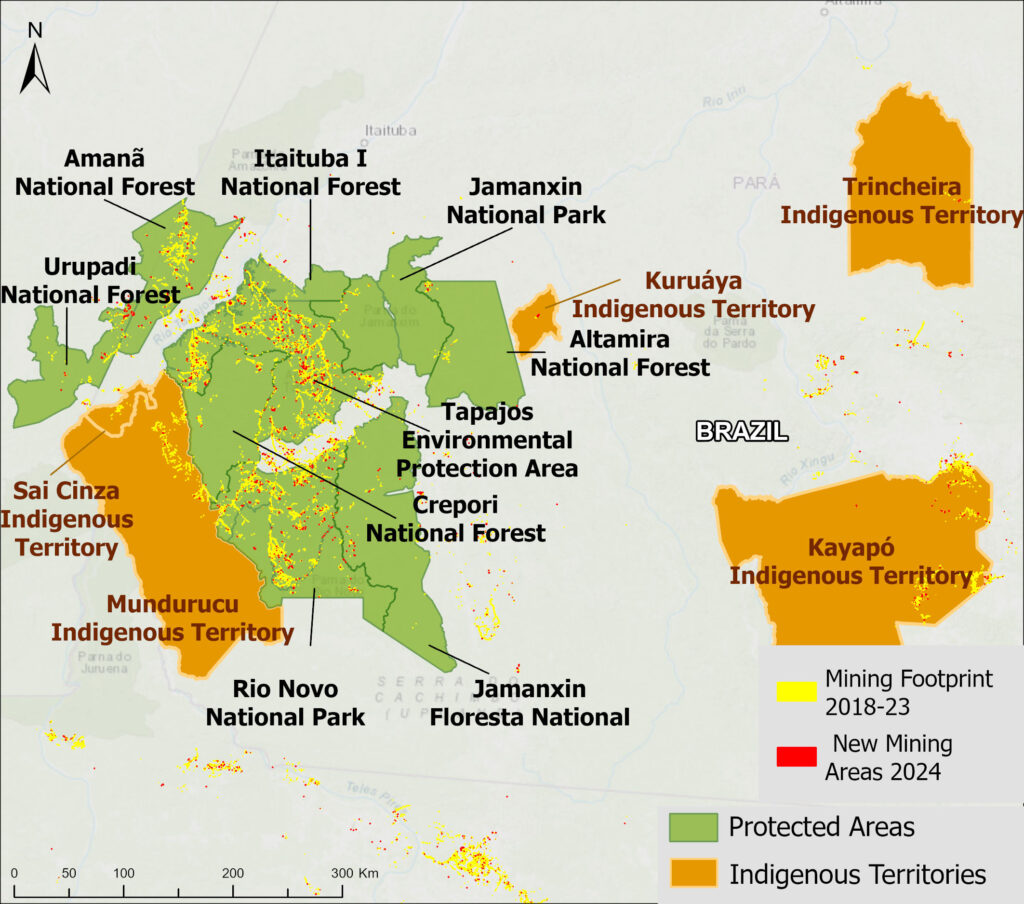

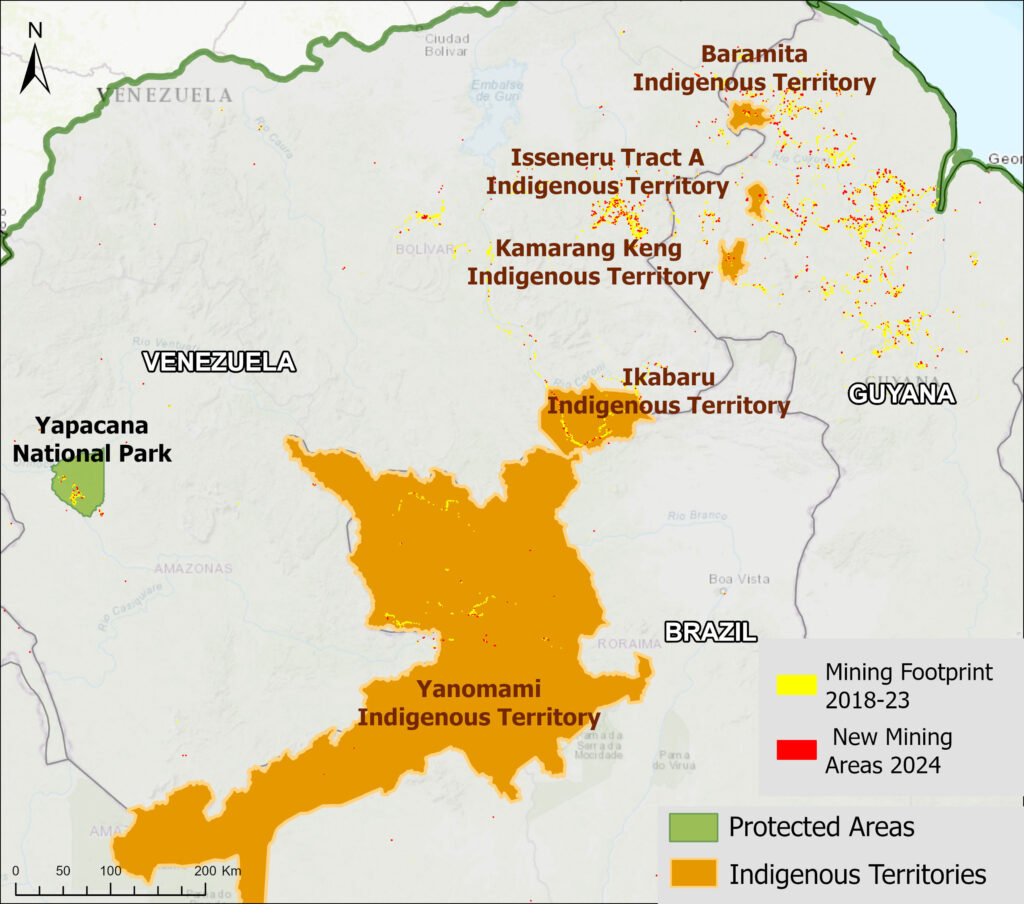

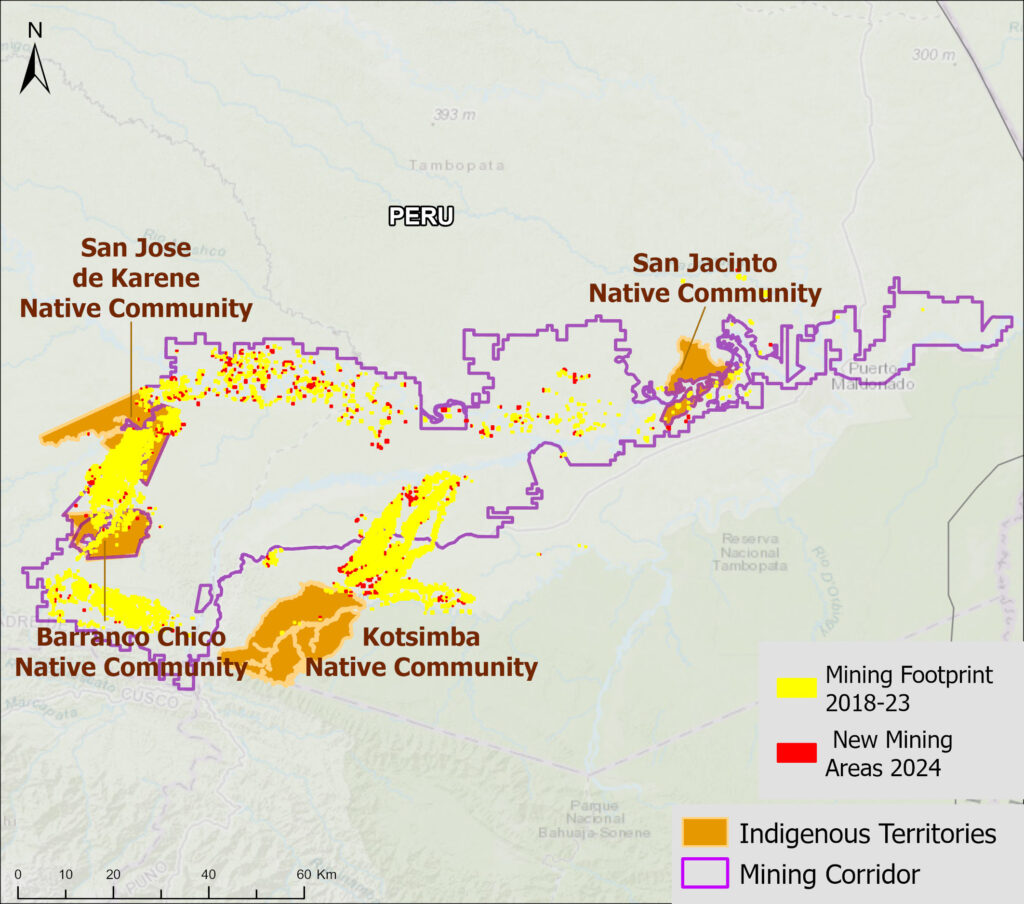

Figure 2a illustrates the top ten for both protected areas and Indigenous territories, in terms of both accumulated mining deforestation footprint and new mining deforestation in 2024. Figures 2b-d show zooms of the three main mining areas: southeast Brazil (2b), Guyana Shield (2c), and southern Peru (2d).

The top nine most impacted protected areas (in terms of accumulated footprint) are all in Brazil, led by Tapajós Environmental Protection Area. This area has lost over 377,000 hectares, followed by Amanã and Crepori National Forests, Rio Novo National Park, Urupadi, Jamanxim, and Itaituba National Forests, Jamanxim National Park, and Altamira National Forest. The top ten is rounded out by Yapacana National Park in Venezuela.

The three most impacted Indigenous territories are also in Brazil: Kayapó, Mundurucu, and Yanomami. Together, these three territories had a mining footprint of nearly 120,000 hectares. Fourth on the list is Ikabaru in Venezuela, followed by three in southern Peru (San Jose de Karene, Barranco Chico, and Kotsimba) with mining impact of over 17,000 hectares. Rounding out the top ten are Sai Cinza and Trincheira/Bacajá in Brazil, and San Jacinto in Peru.

We also estimate the expansion of over 38,000 hectares of new mining deforestation in protected areas and Indigenous territories in 2024. The protected area with the highest levels of new mining deforestation in 2024 was Tapajós Environmental Protection Area (nearly 19,000 hectares), followed by Amanã and Urupadi National Forests in Brazil, Rio Novo and Jamanxim National Parks in Brazil, Crepori National Forest in Brazil, Campos Amazonicos National Park in Brazil, Yapacan National Park in Venezuela, Guyane Regional Park in French Guiana, and Brownsberg Nature Reserve in Suriname.

Finally, the Indigenous territory with the highest levels of new mining deforestation in 2024 was Kayapó in Brazil (over 2,100 hectares), followed by Ikabaru in Venezuela, Yanomami, Aripuana, and Mundurucu in Brazil, Baramita in Guyana, Kuruáya in Brazil, Isseneru and Kamarang Keng, San Jose de Karene in Peu. It is worth noting that Kayapó, Mundurucu, and Yanomami territories in Brazil all experienced declines in the mining deforestation rate in 2024. For example, Yanomami went from its peak in 2021 to the lowest on record in 2024.

Most impacted areas in eastern Brazilian Amazon

Figure 2b. Most impacted areas in eastern Brazilian Amazon. Data: AMW, Amazon Conservation/MAAP.

Most impacted areas in the Guyana Shield

Figure 2c. Most impacted areas in the Guyana Shield. Data: AMW, Amazon Conservation/MAAP.

Most impacted areas in the southern Peruvian Amazon

Figure 2d. Most impacted areas in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Data: AMW, Amazon Conservation/MAAP.

Conclusion & Policy Implications

Despite a recent downward trend in the rate of gold mining deforestation, the cumulative gold mining deforestation footprint continues to grow across the Amazon.

Our analysis shows that over one-third of this mining occurs within protected areas and Indigenous territories, the vast majority in Brazil. However, since the return of the Lula administration in 2023, Brazil has been ramping up enforcement efforts. This has contributed to the rapid decrease in area lost to mining across the Amazon, given Brazil’s outsized contribution to regional figures. This highlights again the importance of protected areas and Indigenous territories as a crucial policy instrument for the protection of the region’s ecosystems.

Although advances have been made in reducing illegal mining from protected areas in southern Peru, it continues to impact several Indigenous territories (MAAP #208, MAAP #196), particularly those surrounding the government-designated Mining Corridor. In fact, the most affected Indigenous territory in Peru, San Jose de Karene, has already lost over a third of its total area to illegal gold mining. These territories are part of a regional organization known as FENAMAD, which has been supporting legal actions to help the government make decisions for a rapid response to illicit activities (such as illegal mining) that affect indigenous territories. This process led to five government-led operations between 2022 and 2024, in three communities: Barranco Chico, Kotsimba and San José de Karene (MAAP #208).

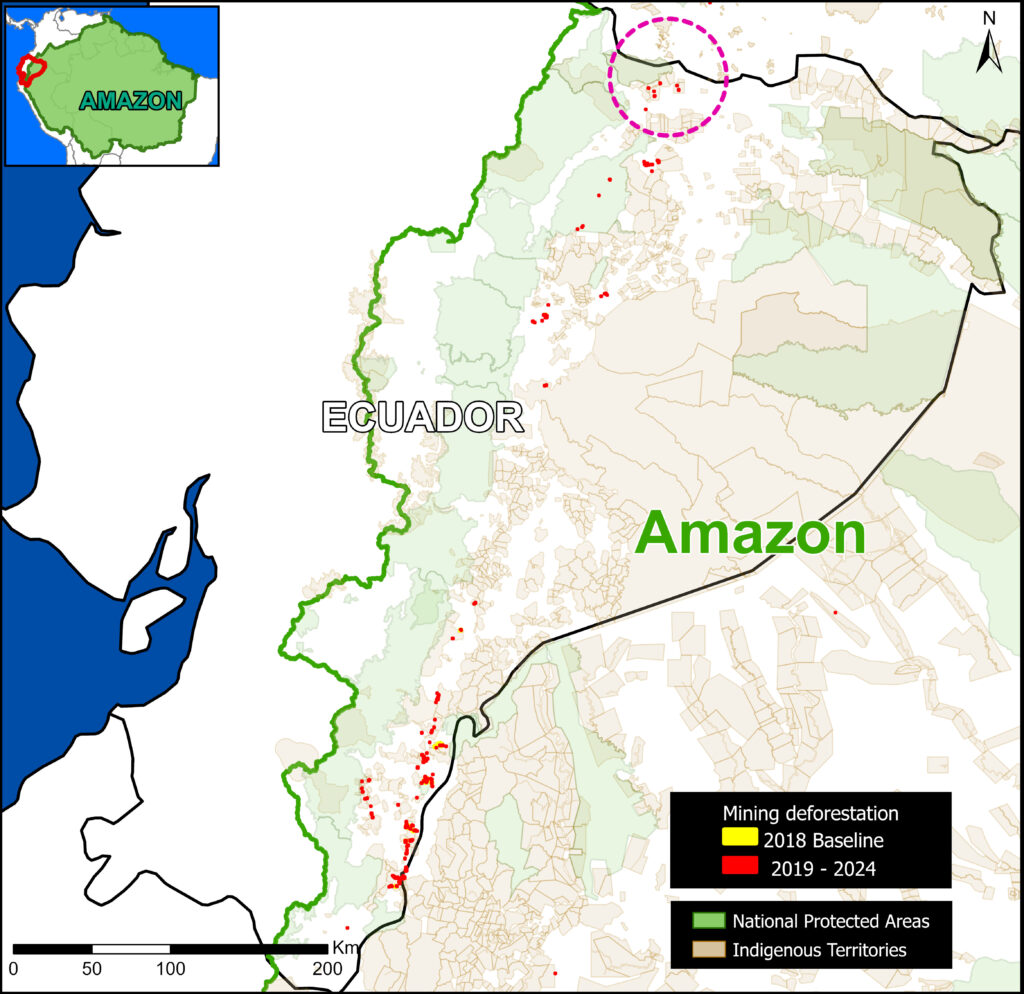

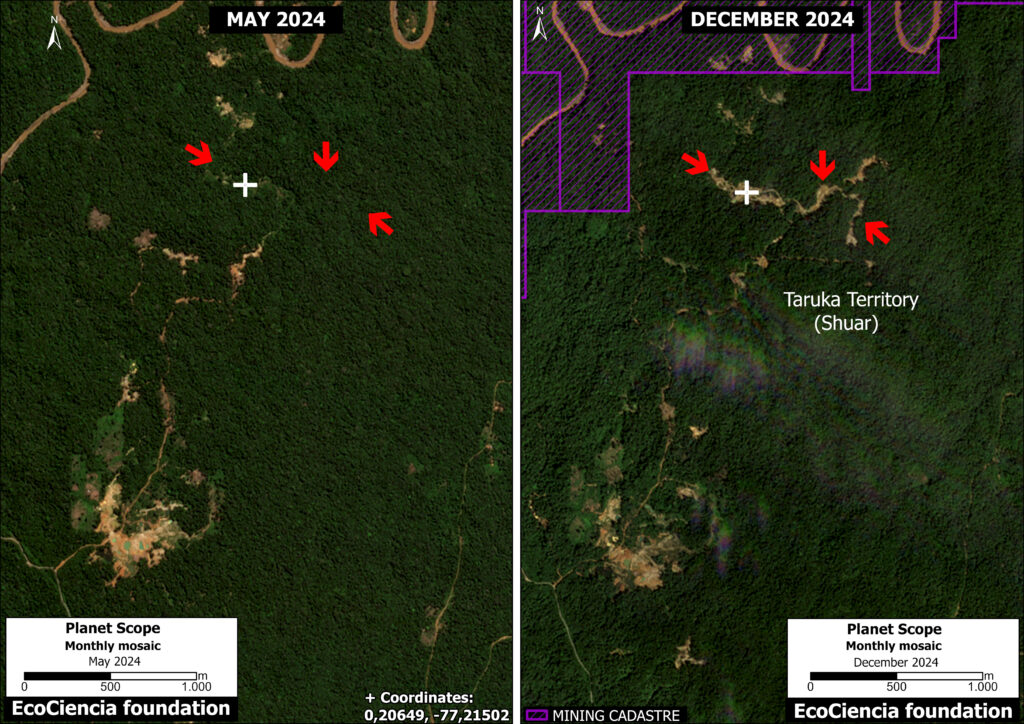

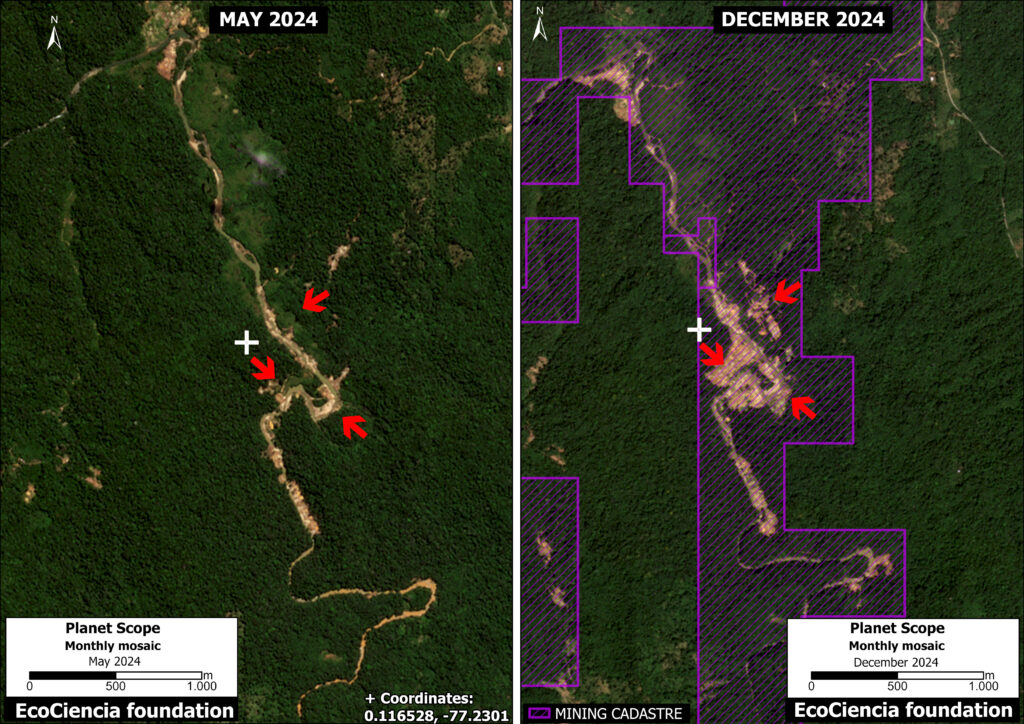

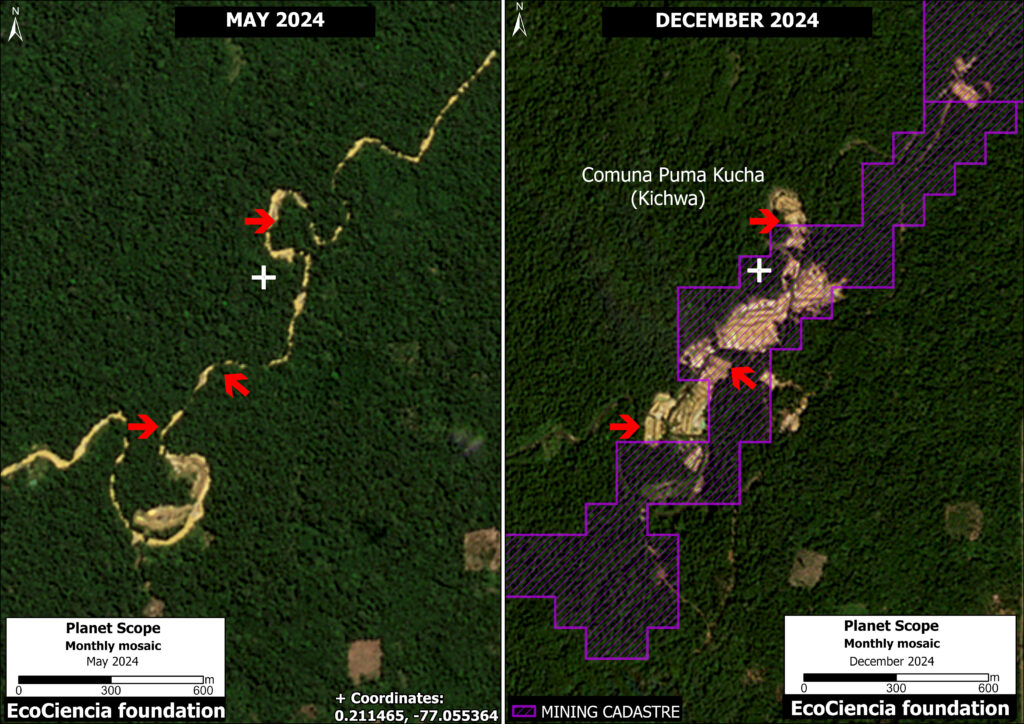

In Ecuador, mining deforestation continues to threaten numerous sites, including protected areas and Indigenous territories, along the Andes-Amazon transition zone (MAAP #206, MAAP #221, MAAP #219). An upcoming series of reports will detail these threats.

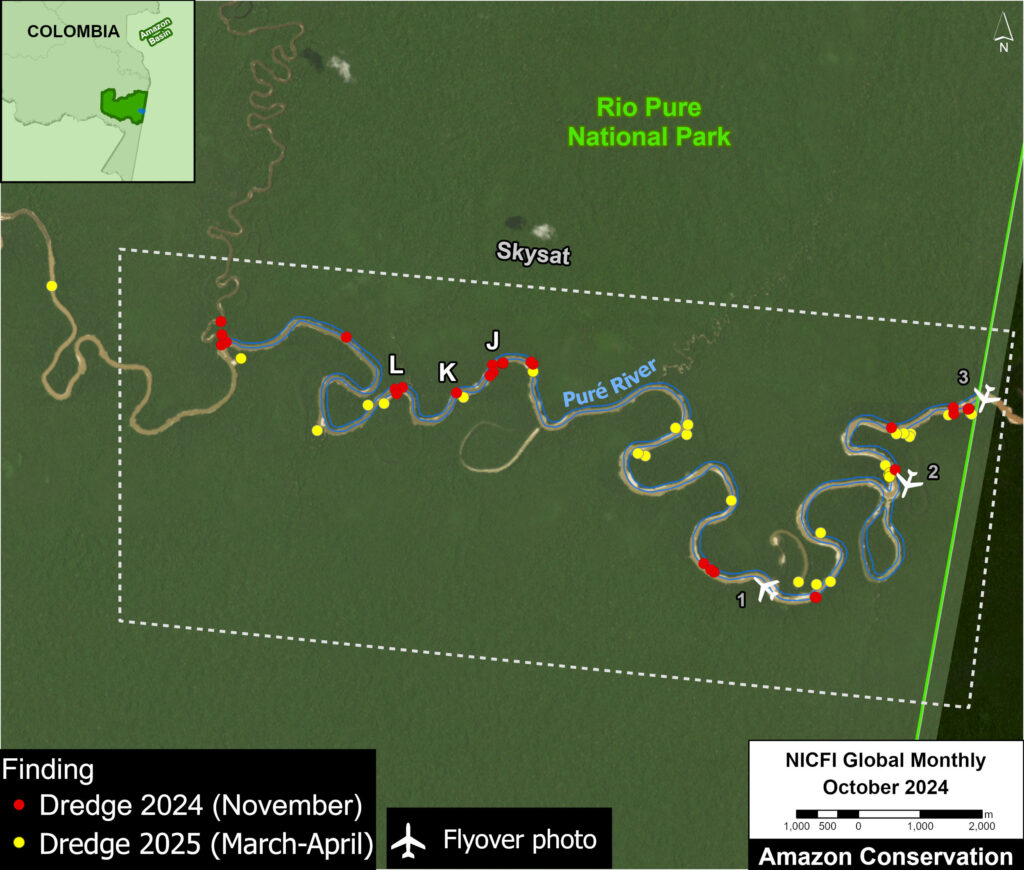

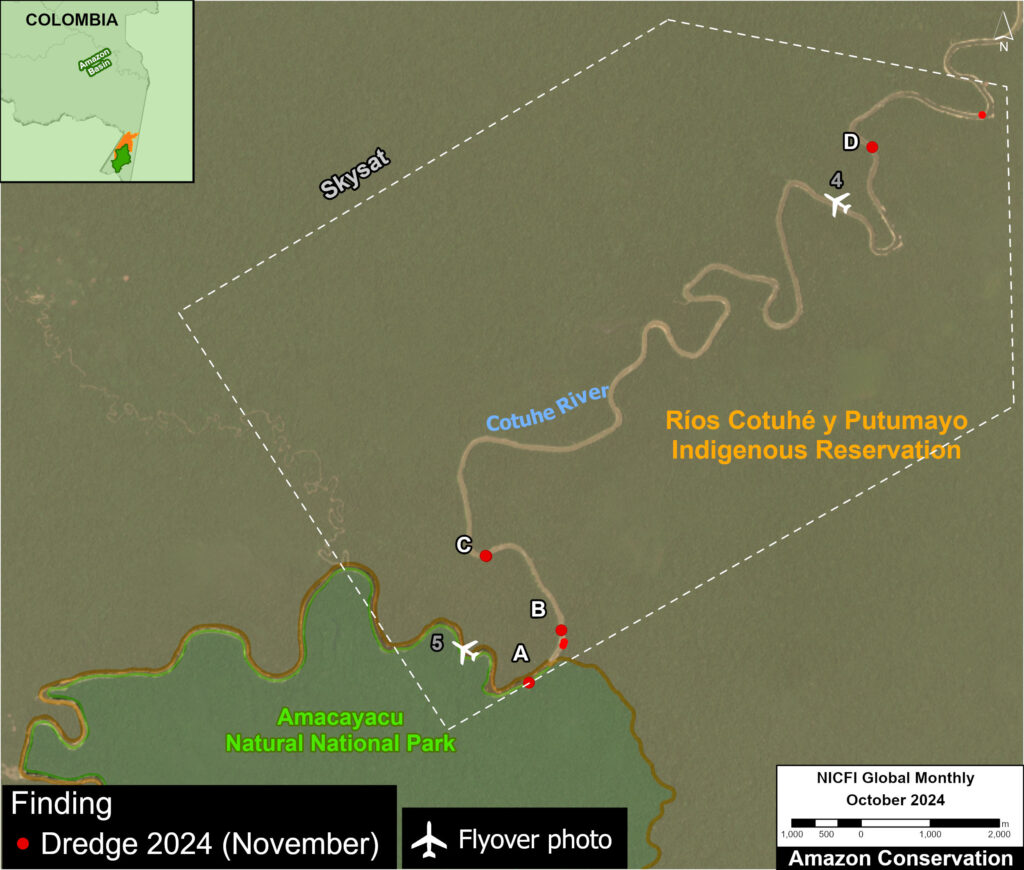

AMW is an emerging and powerful new tool, but it does have some caveats. One is that any mining activity less than 500 square meters may not be accurately detected. For example, we have been monitoring small-scale mining in several protected areas, such as Madidi National Park in Bolivia and Puinawai National Park in Colombia, that are not yet detected by the algorithm. In these cases, direct real-time monitoring with satellites is still needed. These areas will soon be added to the AMW as mining “Hotspots” (MAAP#197).

This is also the case for river-based mining that does not cause a large footprint on the ground. Imagery with very high resolution has revealed active river barge mining in northern Peru (MAAP #189) and along the Colombia/Brazil border (MAAP#197). These areas will also soon be added to the AMW as mining “Hotspots.”

Gold mining in the Amazon is certain to stay a major issue in the coming years as gold prices continue to skyrocket, reaching over $3,000 an ounce in April 2025, driven by global economic uncertainty. While there are encouraging signs of effective enforcement in Brazil, governments here and across the region will have to compete with this rising financial incentive for mining activities.

Tools such as the Amazon Mining Watch, which will eventually publish quarterly updates of newly detected mining deforestation areas, can help governments, civil society, and local community defenders spot new fronts of gold mining and take action in near real-time. In a feature developed by Conservation Strategy Fund (CSF), it will also evaluate the economic costs of socio-environmental mining damages necessary for communities and managers to declare punitive damages.

The only dashboard of this kind to be fully regional in coverage, the AMW can also help foster regional cooperation, in particular in transfrontier areas where a lack of interoperability between official monitoring systems might hamper interventions that are aimed at combating a phenomenon that is linked to other nature crimes and is mostly controlled by international organized crime.

In the coming years, the MAAP and AMW teams will continue to publish both quarterly and annual reports of the dynamic mining situation in each country and across the Amazon, in addition to confidential reports directly to governments and community leaders on the most urgent cases.

Notes

1. Note that in this report, we focus on mining activity that causes deforestation. The vast majority is artisanal or small-scale gold mining, but other mining activities have also been detected, such as iron, aluminum, and nickel mines in Brazil and Colombia. Additional critical gold mining areas in rivers that are not yet causing deforestation (such as in northern Peru, southeast Colombia, and northwest Brazil; see MAAP #197), are not included in this report. This information is not yet displayed in Amazon Mining Watch, but future updates will include river-based mining hotspots.

2. Our data source for protected areas and Indigenous territories is from RAISG (Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information), a consortium of civil society organizations in the Amazon countries. This source (accessed in December 2024) contains spatial data for 5,943 protected areas and Indigenous territories, covering 414.9 million hectares across the Amazon.

Acknowledgments

We thank colleagues from partner organizations around the Amazon for helpful comments on the report, including: Earth Genome, Conservación Amazónica (ACCA & ACEAA) & Federación Nativa del Río Madre de Dios y Afluentes (FENAMAD), Fundación EcoCiencia, Fundación para la Conservación y el Desarrollo Sostenible (FCDS), and Instituto Centro de Vida (ICV) & Instituto Socioambiental (ISA).

This report was made possible by the generous support of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.