Author: Matt Finer

MAAP #235: AI-powered detection of Amazon gold mining deforestation in real-time

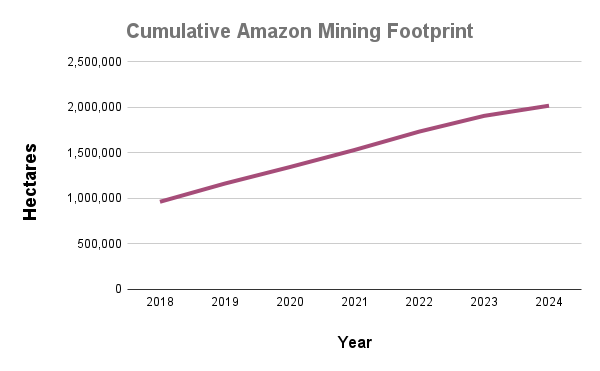

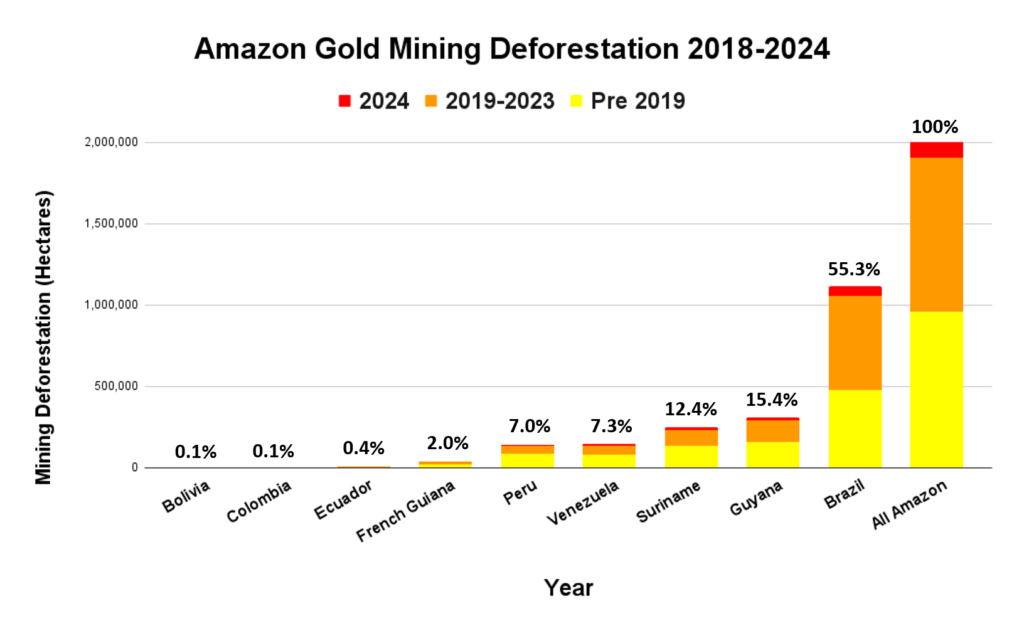

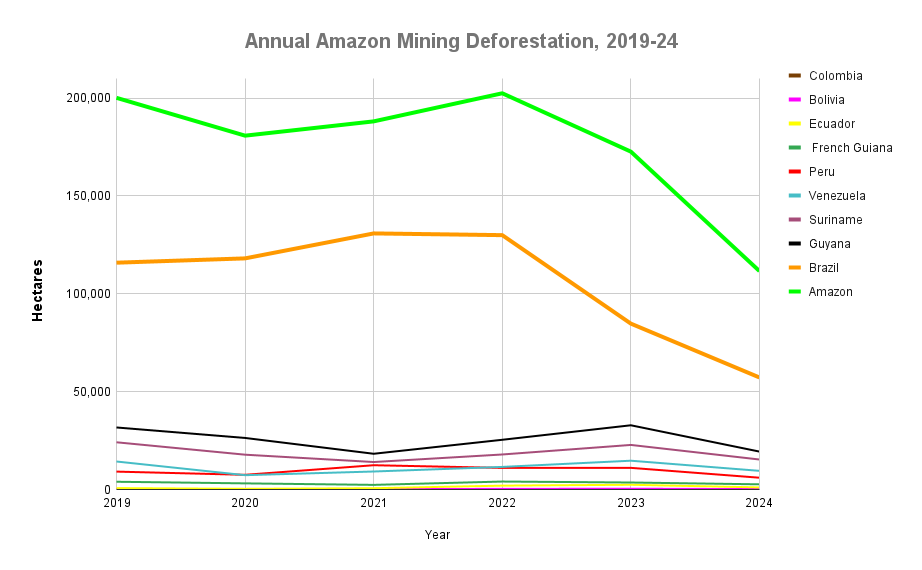

As gold prices continue to skyrocket and shatter historical records, small-scale, but widespread, gold mining activity also continues to be one of the major deforestation drivers across the Amazon.

In collaboration with its network of partners in the region, MAAP has produced many reports documenting the expansion of gold mining across the Amazon over the years, highlighting often previously undocumented cases (see archive).

Given the vastness of the Amazon, however, it has been a challenge to systematically detect all new mining fronts in real-time. Such a timely and comprehensive system is crucial to ensure that monitoring can be the basis for a swift and consistent enforcement response from authorities.

Since 2023, Amazon Conservation, in partnership with Earth Genome and the Pulitzer Center, has been developing an online dashboard known as Amazon Mining Watch (MAAP #226). This online tool automates the analysis of satellite imagery through machine learning to identify areas affected by mining across the entire Amazon, from 2018 to 2024.

In a major advance, we are glad to announce that Amazon Mining Watch (AMW) will now move to quarterly updates for this data, achieving systematic near-real-time detection of new artisanal gold mining fronts across the region.

Additional functionalities have been added to the AMW that will enhance the analysis related to illegal gold mining in the biome, namely: an analysis of the legality of mining sites, and an economic valuation of the social and environmental damage through the mining impacts calculator tool (see Annex).

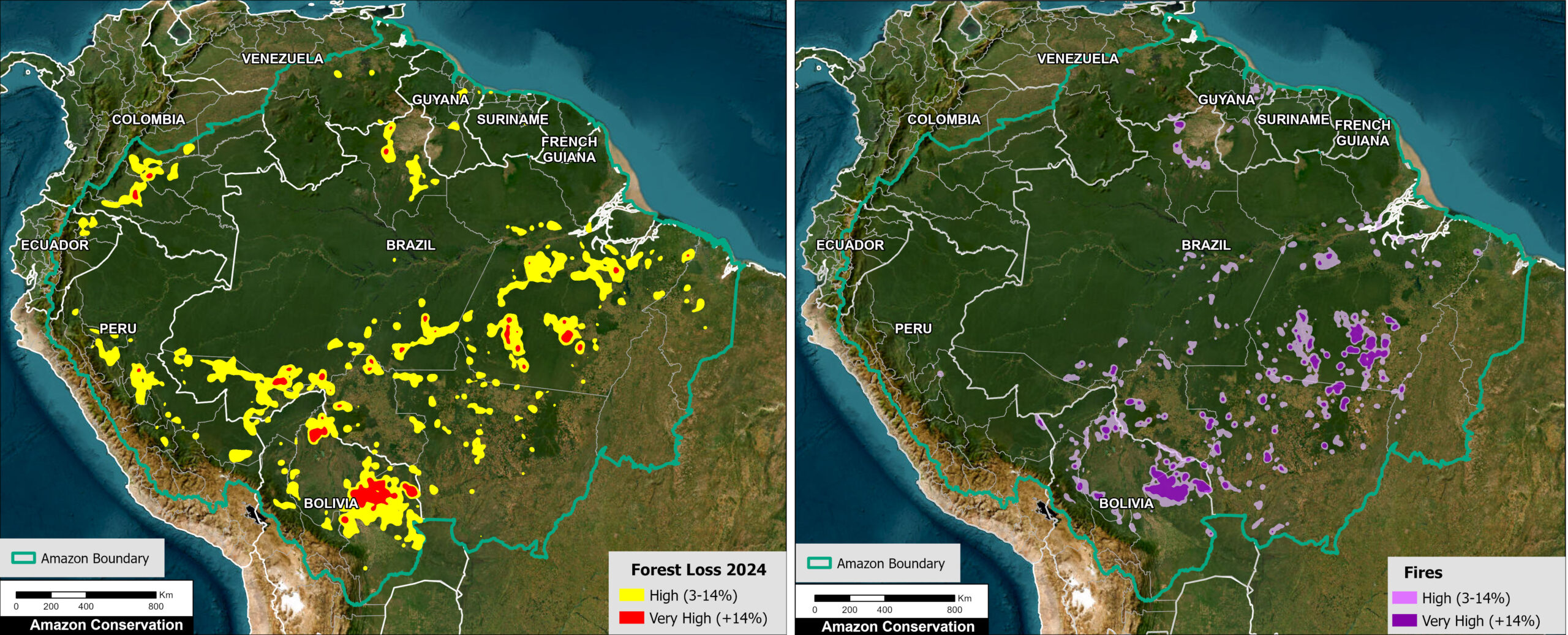

FIRST QUARTERLY UPDATE REPORT: MINING EXPANSION ACROSS THE AMAZON

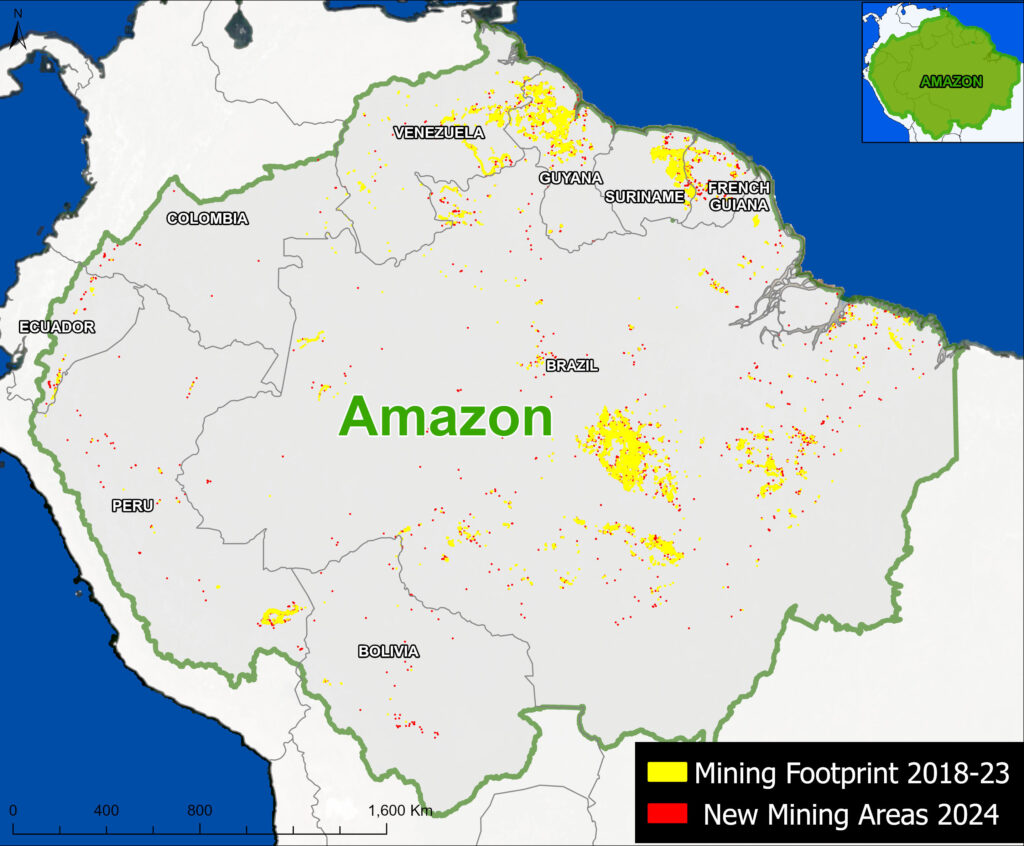

Here, we present our first quarterly update report based on this fresh data for quarters 2 and 3 of 2025 (April-September 2025). The following Base Map shows the locations of recent (Q3 of 2025) mining deforestation across the Amazon, in relation to the cumulative mining impact area previously detected.

Key findings from the first quarterly updates include:

- We confirm the recent expansion of gold mining in all nine countries of the Amazon (37,109 hectares in 2025).

- Brazil registered the largest recent mining expansion area (15,538 ha in 2025), followed by Peru (6,511 ha) and Guyana (4,942 ha).

In addition, Venezuela, Suriname, Ecuador, and Bolivia all had over 2,000 hectares of recent impact. - Guyana and Suriname have the largest area of mining-related deforestation relative to their size.

- The total area of gold mining expansion in the second quarter of 2025 represents over 19,000 hectares

- Mining expansion accelerated in the third quarter (July-Sept) of 2025, with over 17,000 hectares of forest lost to mining, almost twice the rate observed in the first half of the year.

- Despite experiencing relatively widespread river-based mining, Colombia is the only country in the region that had been so far mostly spared from the impacts of gold mining on land (also referred to as “alluvial mining”). The recent crossing of alluvial mining along the Rio Puré from Brazil into Colombia, further described below, could put an end to this exception and explains almost single-handedly the sharp uptick seen in the last quarter (+58%).

- In 2025, over 200 (222) protected areas and Indigenous territories experienced new mining activity, and therefore likely to represent illegal mining. The estimated mined area of these 2025 mining events is over 14,000 hectares (14,004 ha). Of this total, 56% occurred in protected areas, and 44% in Indigenous territories.

CASES OF RECENT GOLD MINING DEFORESTATION ACROSS THE AMAZON

The Base Map shows the locations of confirmed recent (Q3 of 2025) mining deforestation across the Amazon, in relation to the cumulative mining impact area.

In each set of panels displayed below, we show high-resolution satellite imagery before (left panel) vs after (right panel) the recent gold mining deforestation. The red polygons indicate the pixels highlighted by the AI model as a new quarter 3 mining deforestation event. Yellow polygons are previously detected pixels.

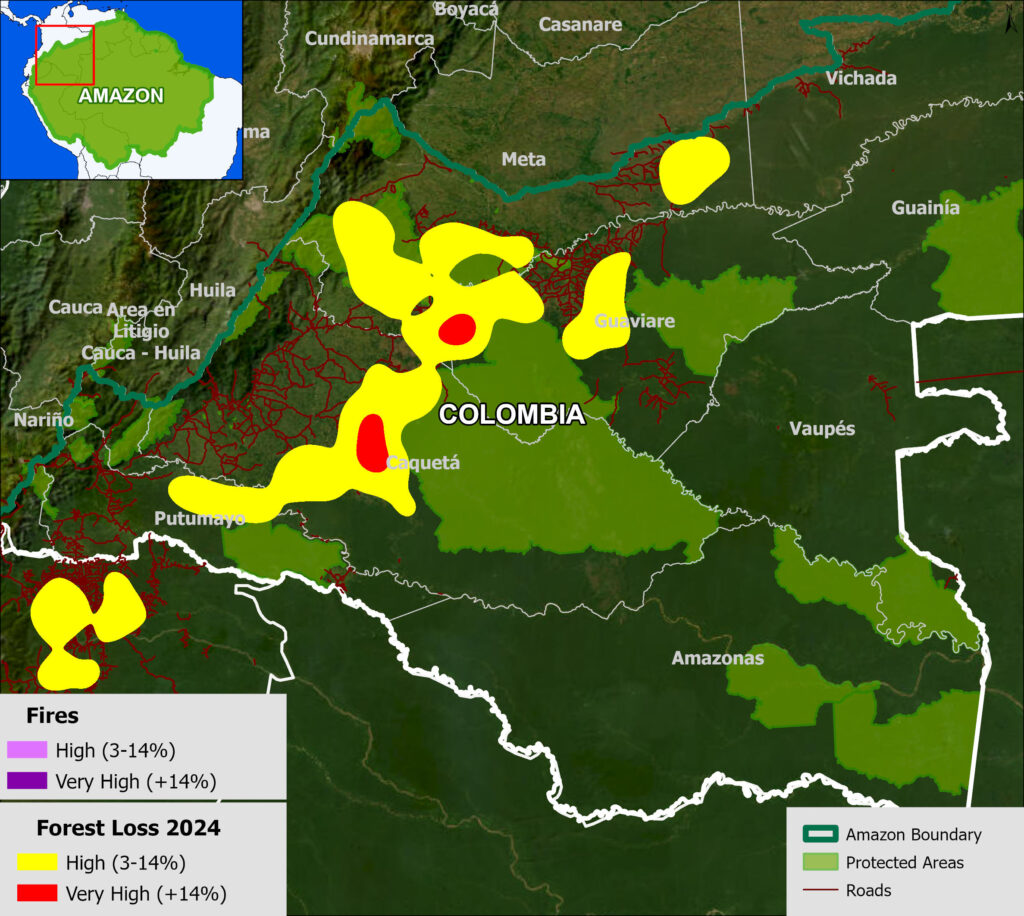

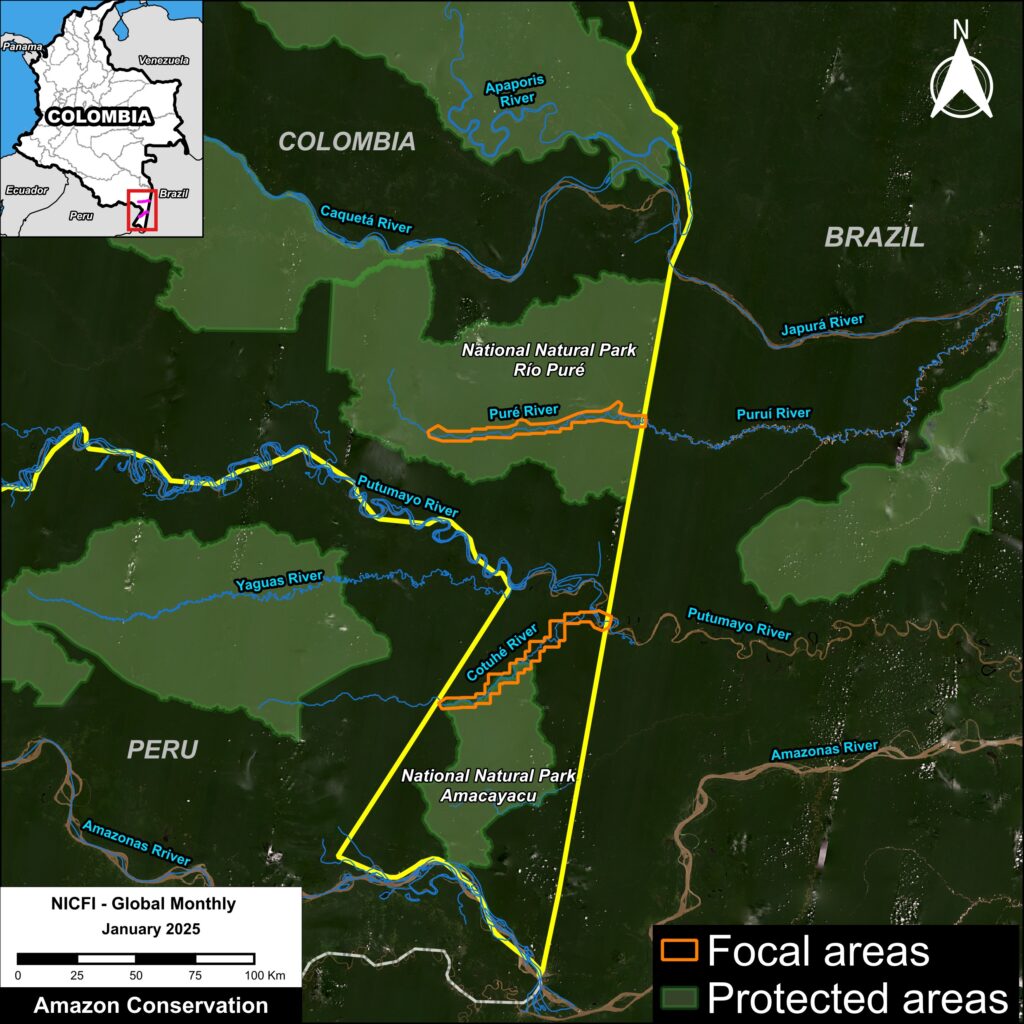

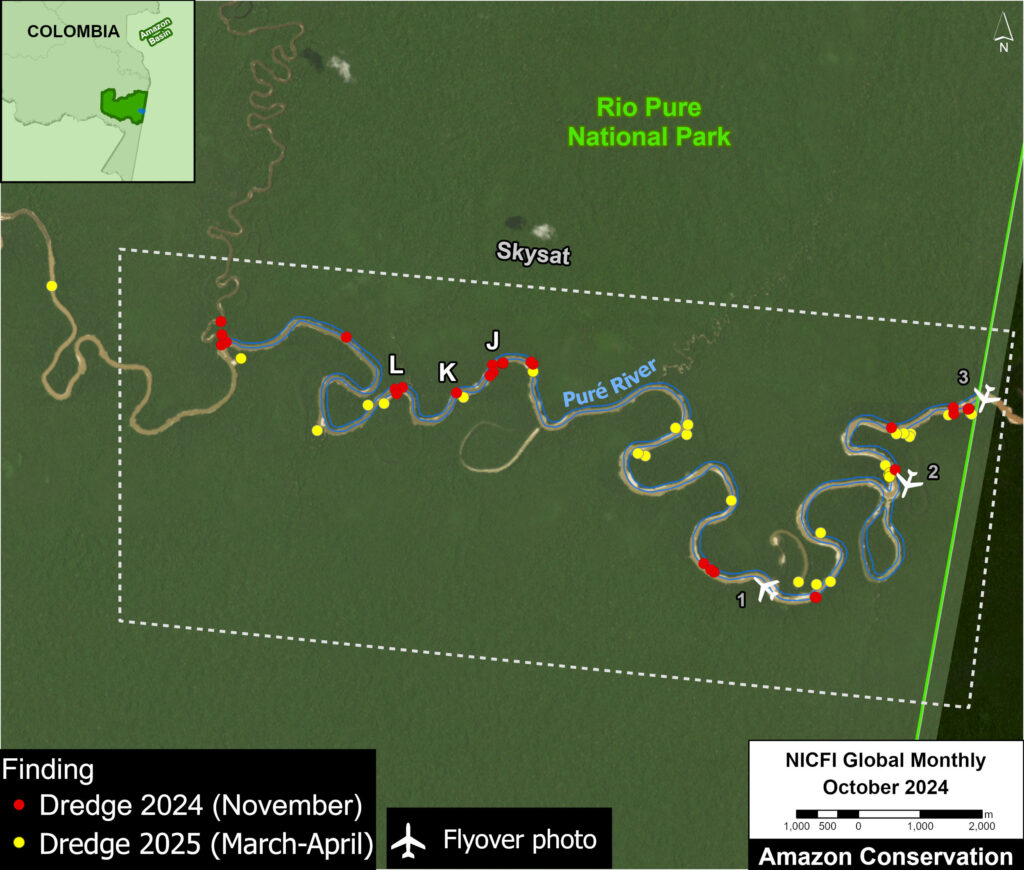

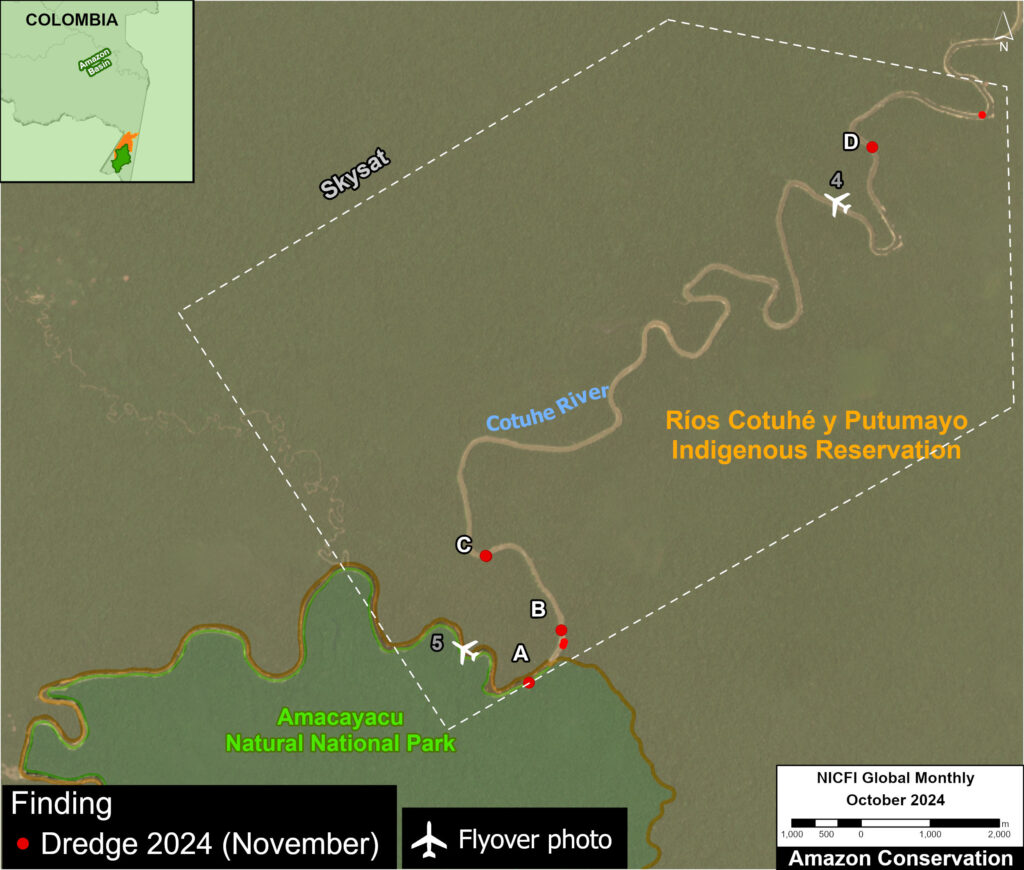

A. Rio Puré, Colombia-Brazil border

The Q3 2025 detection revealed that alluvial gold mining has, for the first time, crossed the border between Brazil and Colombia, into the Rio Puré National Park. A relatively large-scale operation appears to be ongoing and expanding in one of the most remote corners of the Amazon, affecting one of the largest intact forest landscapes still remaining globally.

Mining along the Rio Puré is estimated to have started around 2018, gradually expanding along the whole Brazilian portion of the river between the border with Colombia and where it meets the Japurá river, itself one of the major tributaries of the Amazon river. The clear difference in the river’s color between the last two quarters also reveals the amount of sediments released from the mining operation, which greatly increased water turbidity.

The verified expansion of the mining into the Colombian side, under National Park status, makes this a clear case for transboundary collaboration between the enforcement authorities of Brazil and Colombia. This incursion from Brazil represents the vast majority of mining-related deforestation in the country for the last quarter, and an almost 60% increase in area compared to the previous 7 years.

This case registers as a Very High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on Amazon Mining Watch.

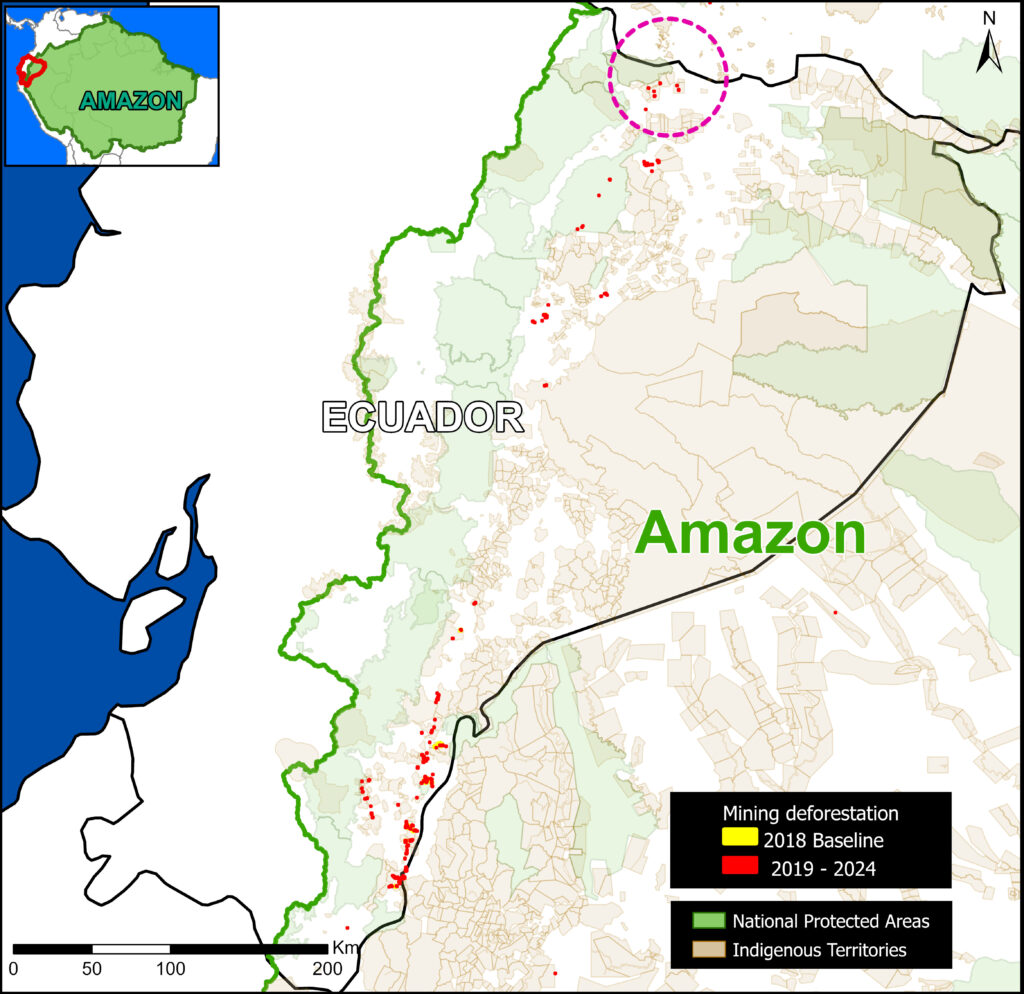

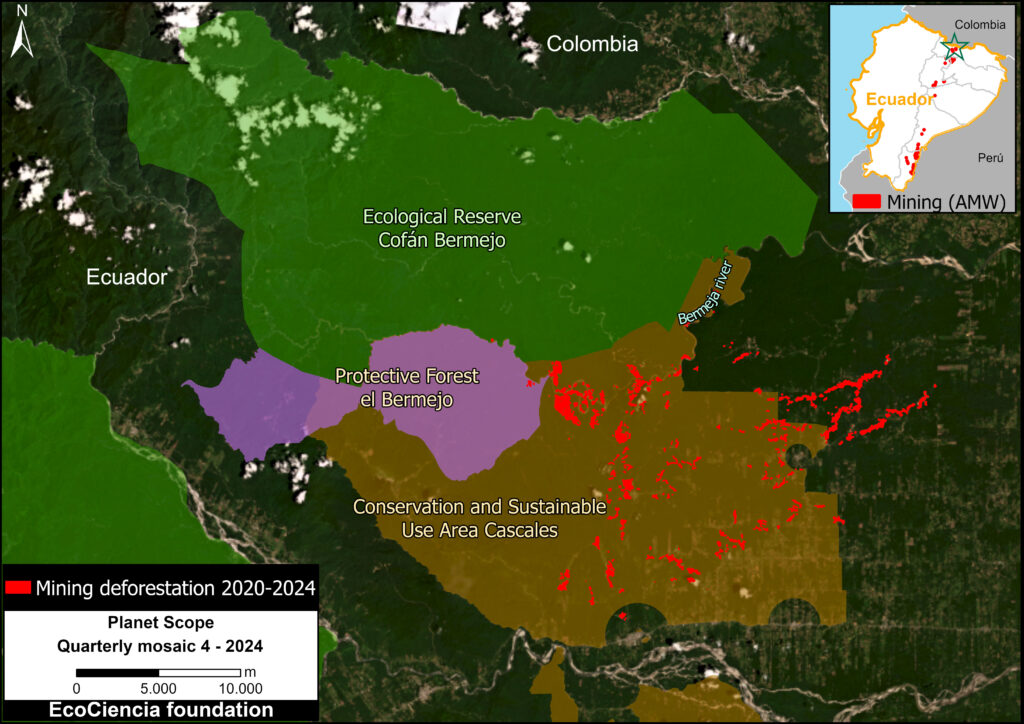

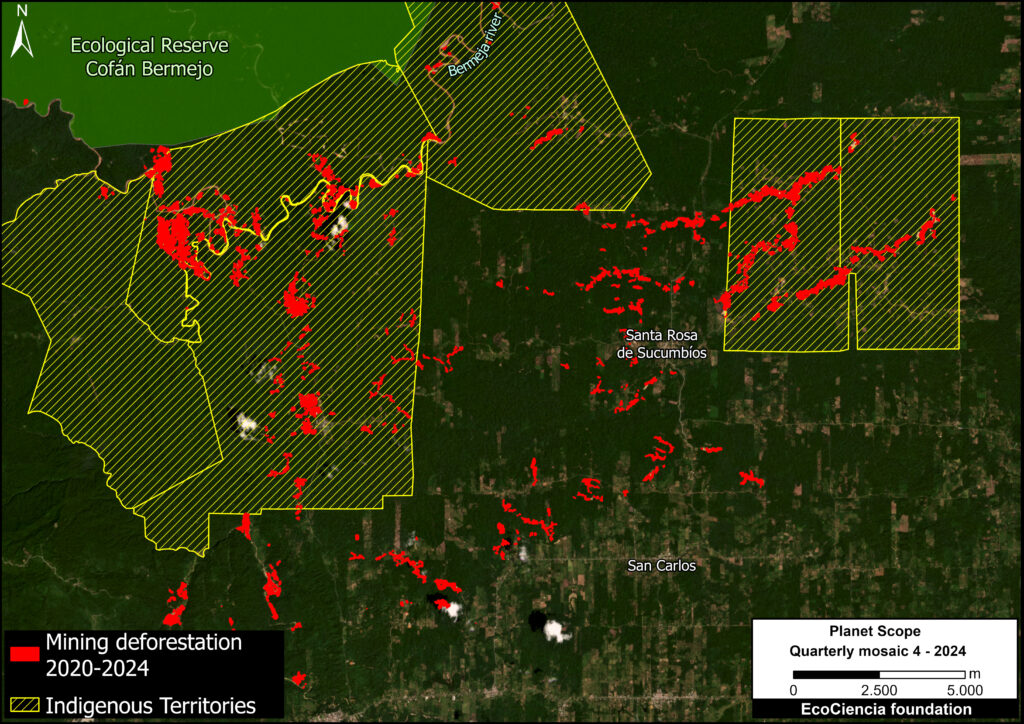

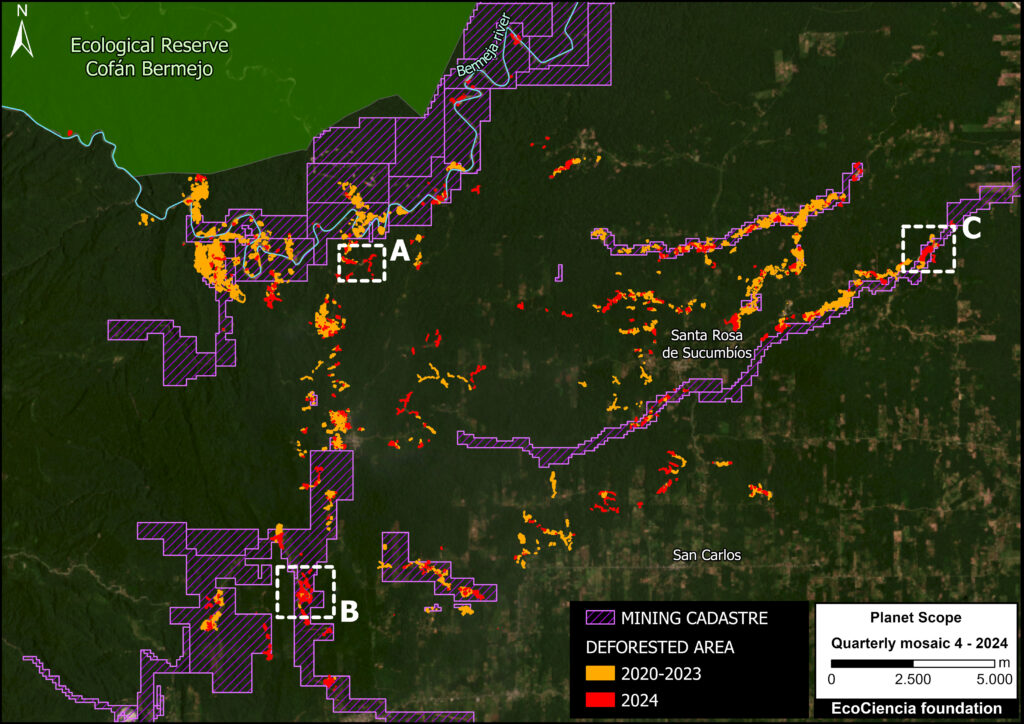

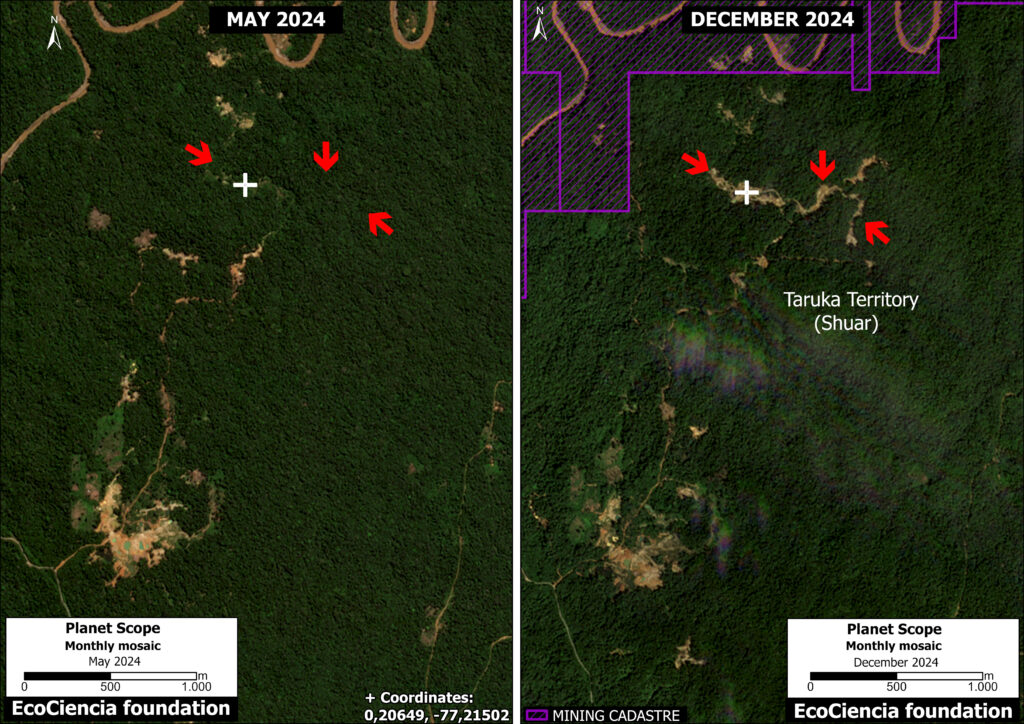

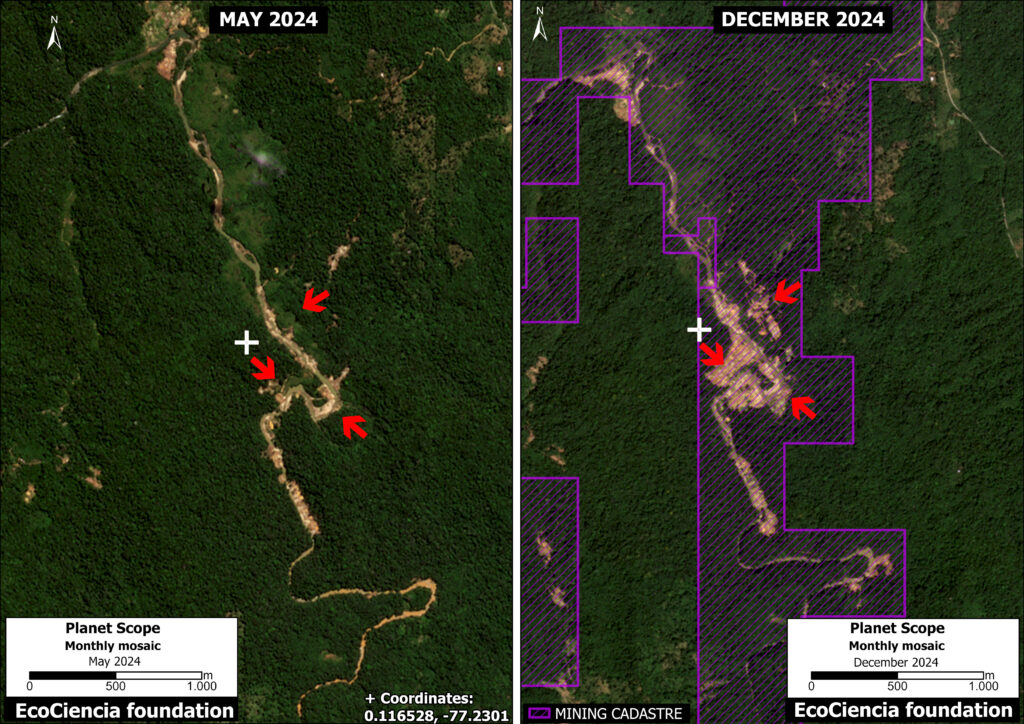

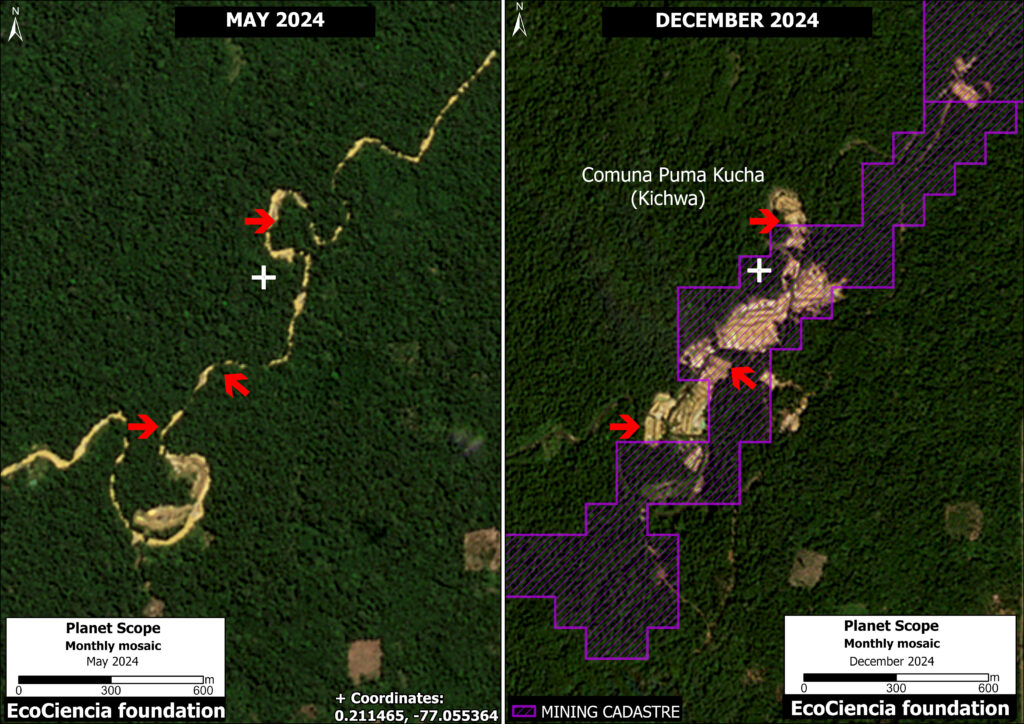

B. Northern Ecuador

Figure B shows the recent mining deforestation outside of the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon. This area has experienced increasing mining impact in recent years, as further described in MAAP #227. Note that this mining activity is within the Puma Kucha, Indigenous territory. This case registers as a High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on Amazon Mining Watch.

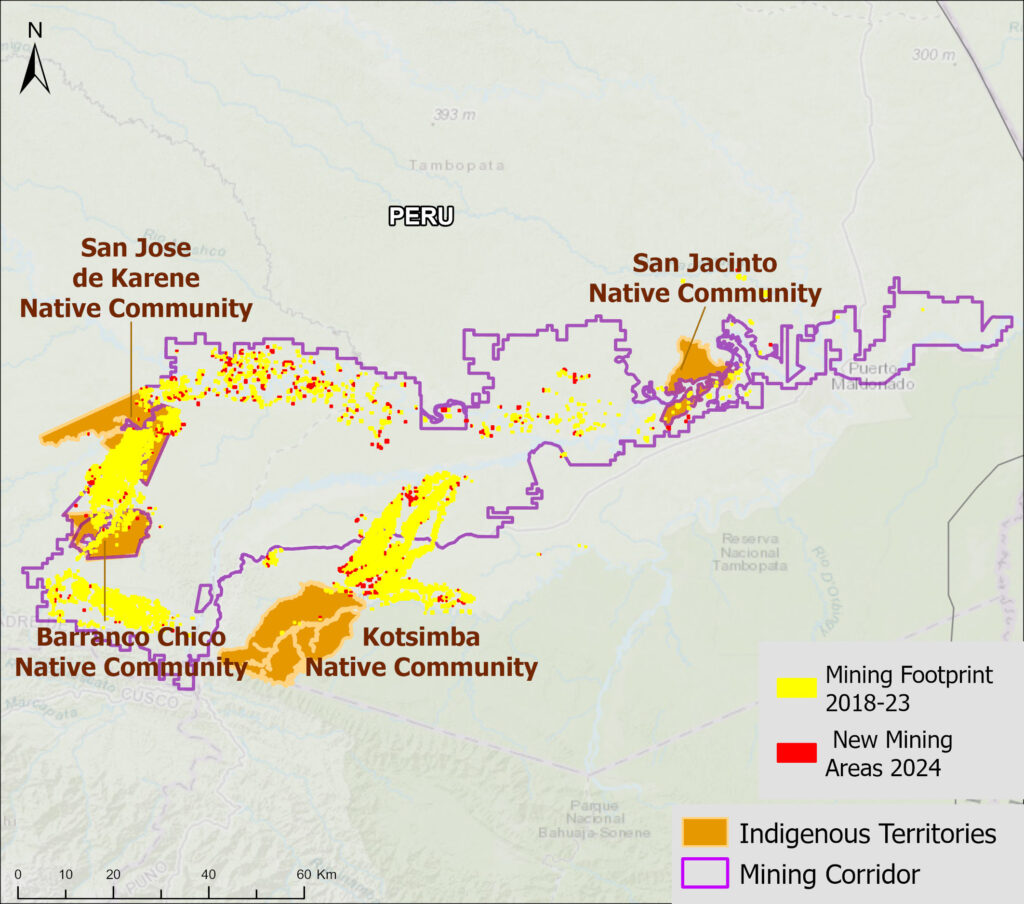

C. San José de Karene Indigenous Territory, Peru

Figure C shows the recent mining deforestation in the San José de Karene Indigenous Territory in the southern Peruvian Amazon. As detailed in MAAP #208, much of the illegal mining deforestation in the southern Peruvian Amazon is occurring within the territory of Native Communities. This case registers as a High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on Amazon Mining Watch.

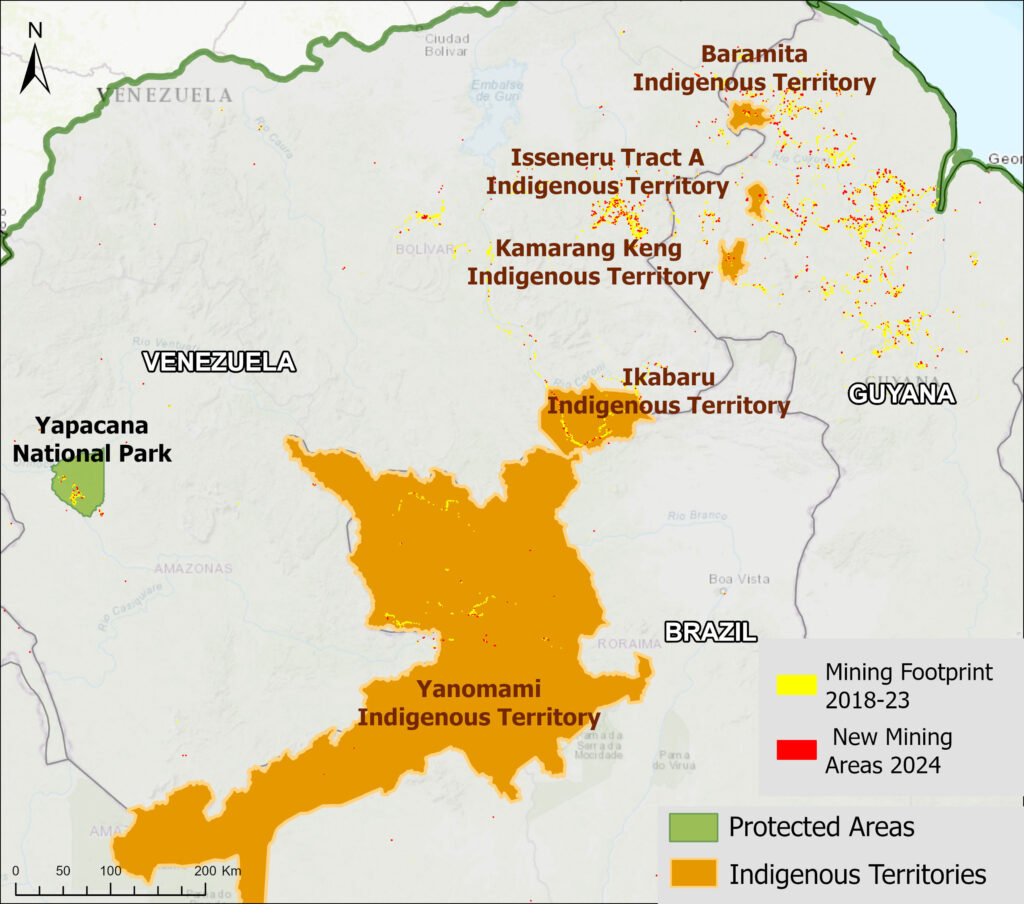

D. Pemon Indigenous Territory, Venezuela

The Pemon Indigenous territory stands out as the area most affected by gold mining in the last quarter, across all protected areas and indigenous territories of the region. The Pemon’s traditional territory is divided between an officially demarcated area, where mining increased by more than 100 hectares in the last quarter, and a much greater and yet-to-be-demarcated area, where mining increased by a staggering 700 ha in the last quarter only, a steep acceleration from the first semester of 2025. The Pemon’s territory encompasses part of the outstanding geological wonder Mount Roraima, a flat-topped mountain of immense cultural significance to local peoples. Mount Roraima harbors unique biodiversity and inspired Michael Crichton’s novel “The Lost World”.

This case registers as a High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on the Amazon Mining Watch.

Brazil

Figure E shows the recent mining deforestation in the Amapá State Forest in the northeastern Brazilian Amazon. The forest is managed to benefit local communities through initiatives like sustainable agroecology and improved management of wood and non-forest products. This marks the first time this area has been highlighted by MAAP. This case registers as a Very High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on the Amazon Mining Watch.

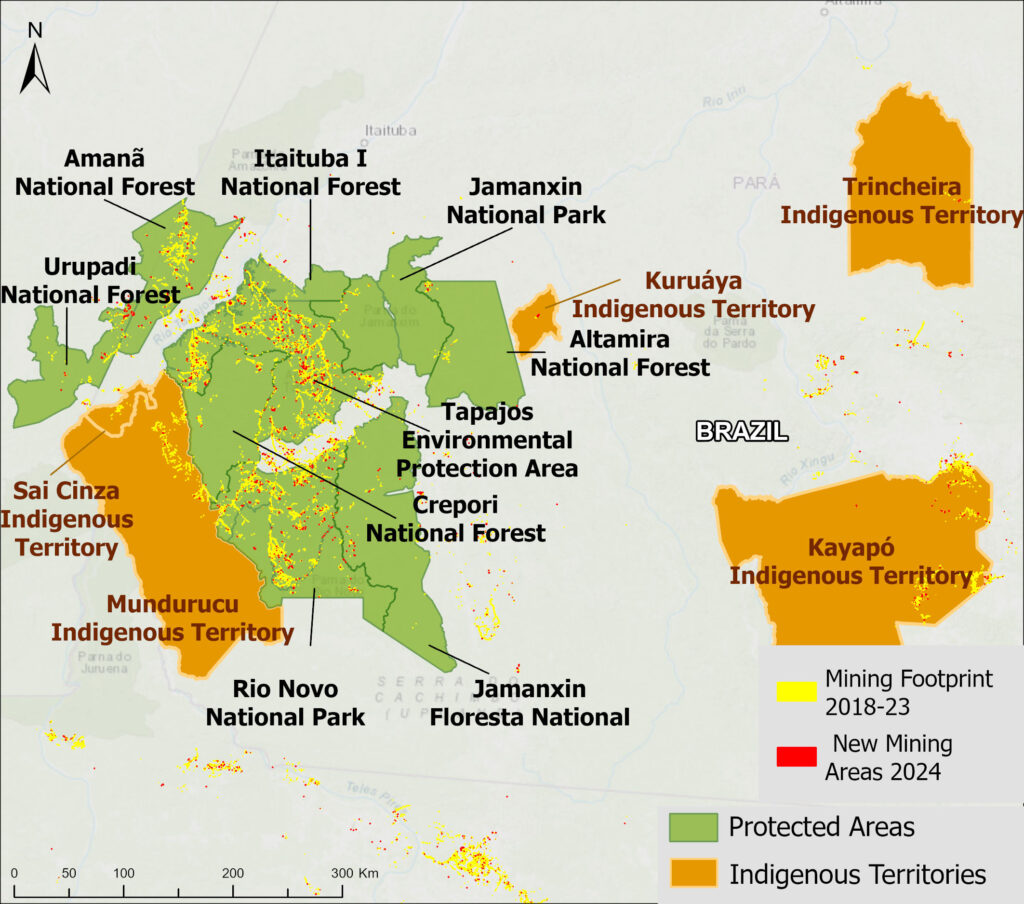

Figure F shows the recent mining deforestation in the Tapajós Environmental Protection Area in the central Brazilian Amazon. It is in the western portion of the BR-163 Sustainable Forest District. As noted in MAAP #226, Tapajós EPA is one of the Amazon’s top ten most impacted protected areas (in terms of accumulated footprint), including high levels of new mining deforestation in 2024. This case registers as a Very High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on the Amazon Mining Watch.

Figure G shows the recent mining deforestation in Jamanxim National Forest in the central Brazilian Amazon. As noted in MAAP #226, Jamanxim NF is one of the Amazon’s top ten most impacted protected areas (in terms of accumulated footprint). This case registers as a Very High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on the Amazon Mining Watch.

Figure H shows the recent mining deforestation in the Grão-Pará Ecological Station in the northeast Brazilian Amazon, along the border with Guyana. It is the largest strictly protected tropical forest research station in the world. This marks the first time this area has been highlighted by MAAP. This case registers as a Very High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on the Amazon Mining Watch.

Suriname

Figure I show recent mining deforestation in northeast Suriname. This marks the first time this specific area has been highlighted by MAAP. This case registers as a High probability of being illegal based on the legality layer. For more information, consult the scene on the Amazon Mining Watch.

Guyana

Figure J shows the recent mining deforestation in northwestern Guyana, near the border with Venezuela. This marks the first time this specific area has been highlighted by MAAP. For more information, consult the scene on the Amazon Mining Watch.

Annex

New functionality: Legality of mining sites

Based on an analysis of potential overlaps with land designations and applicable regulations, a location-based presumption of illegality of mining operations was incorporated into the AMW. We classified the presumption of illegality from very high to low, using the following descriptions:

- Very High: Activity is occurring without a permit and within a protected area that doesn’t allow for any kind of resource exploitation

- High: Activity if occurring outside of any explicit concession for doing so

- Medium: Activity is happening within a concession, but active status could not be verified and/or concession doesn’t meet legal requirements

- Low: Activity is happening within active concession, but compliance with all requirements could not be verified

This functionality is available for 5 countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, and will be extended to the rest of Amazonian countries in 2026. Based on national datasets of land designations, it provides an immediate overview of the likelihood of illegality of ASM in any area of analysis.

New functionality: Mining impacts calculator

The Mining Impacts Calculator, developed by Conservation Strategy Fund, is a tool to assess the social and environmental damage caused by gold mining. The tool uses an economic formula to estimate effects on the environment and society by inputting variables such as the size of the mine, the amount of gold produced and the time of extraction. The automated formula uses average mining productivity and data-driven impact parameters to deliver contextualized data to the user.

The calculator can be used for three main purposes: to estimate social and environmental damage values to calculate the amount of financial compensation needed to mitigate the costs, to estimate the most efficient investment amounts for future impact planning and the prevention of negative impacts, and to estimate the recommended amount of investment in mercury-free technologies needed.

Notes/Methodology

Note that in this report, we focus on mining activity that causes deforestation. The vast majority is artisanal or small-scale gold mining, but other mining activities have also been detected, such as iron, aluminum, and nickel mines in Brazil and Colombia. Additional critical gold mining areas in rivers that are not yet causing deforestation (such as in northern Peru (MAAP #233), southeast Colombia (MAAP #228), and northwest Brazil (MAAP #197), are not included in this report. This information is not yet displayed in Amazon Mining Watch, but future updates will include river-based mining hotspots.

Our data source for protected areas and Indigenous territories is from RAISG (Amazon Network of Georeferenced Socio-Environmental Information), a consortium of civil society organizations in the Amazon countries. This source (accessed in December 2024) contains spatial data for 5,943 protected areas and Indigenous territories, covering 414.9 million hectares across the Amazon.

Amazon Mining Watch (AMW) is a partnership between Earth Genome, the Pulitzer Center’s Rainforest Investigations Network, and Amazon Conservation. The algorithm is based on 10-meter-resolution imagery from the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellite and produces 480-meter resolution pixelated mining deforestation alerts. Although the data is not designed for precise area measurements, it can be used to give timely estimates needed for management and conservation purposes.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible by the generous support of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

MAAP #234: Illegal gold mining in Yapacana National Park, including on top of Yapacana Tepui (Venezuelan Amazon)

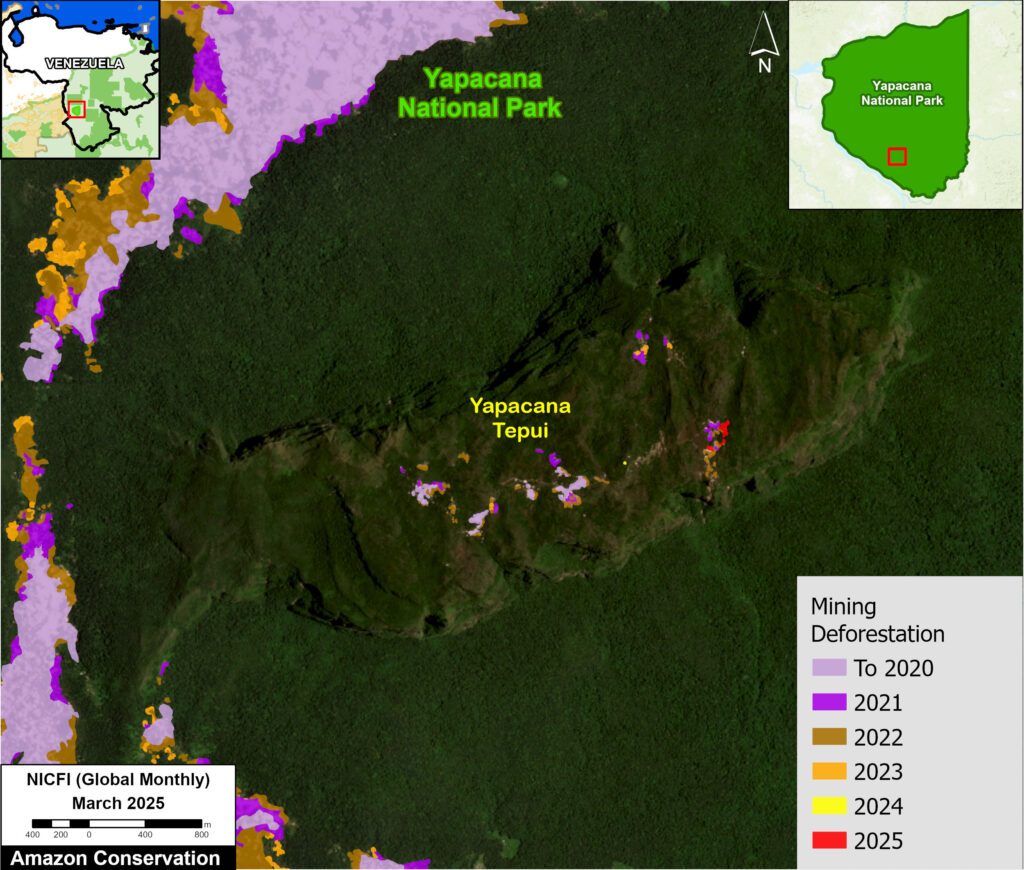

In a series of previous reports, and in collaboration with SOS Orinoco, we have tracked the illegal gold mining deforestation and related impacts in Yapacana National Park, located in the Venezuelan Amazon.

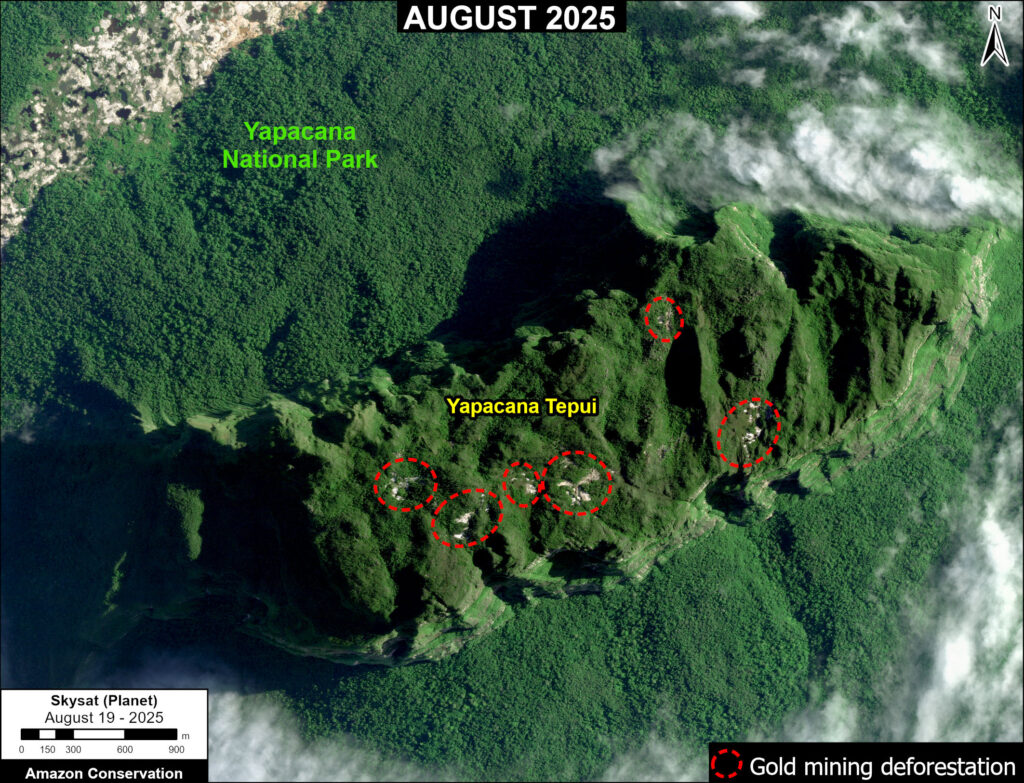

Critically, some of this illegal mining activity has been happening on top of the Yapacana tepui (see red circles in Intro Image).

Tepuis are stunning table-top mountains found in northern South America. They are considered sacred by indigenous groups of the Guiana Shield region; in fact, the word tepui means “mountain” in the local indigenous (Pemon) language.

In 2022, we published an urgent report about the illegal mining on top of the Yapacana tepui (MAAP #169). In this report, we documented over 400 points of mining camps and heavy machinery, indicating an organized and large-scale operation, causing the deforestation of 8.8 hectares on top of the tepui.

Given the importance of this finding, the Washington Post published a high-profile article on the subject, further exposing the severity of the illegal mining on the tepui.

In response, the Venezuelan government conducted a military operation against illegal mining activity on the tepui in December 2022.

In early 2024, we reported that all illegal mining camps and equipment on top of the tepui had been removed (MAAP #207). Indeed, we detected no additional mining deforestation on top of the tepui during 2024.

However, we now present evidence that the illegal mining activity has resumed on top of the tepui in 2025.

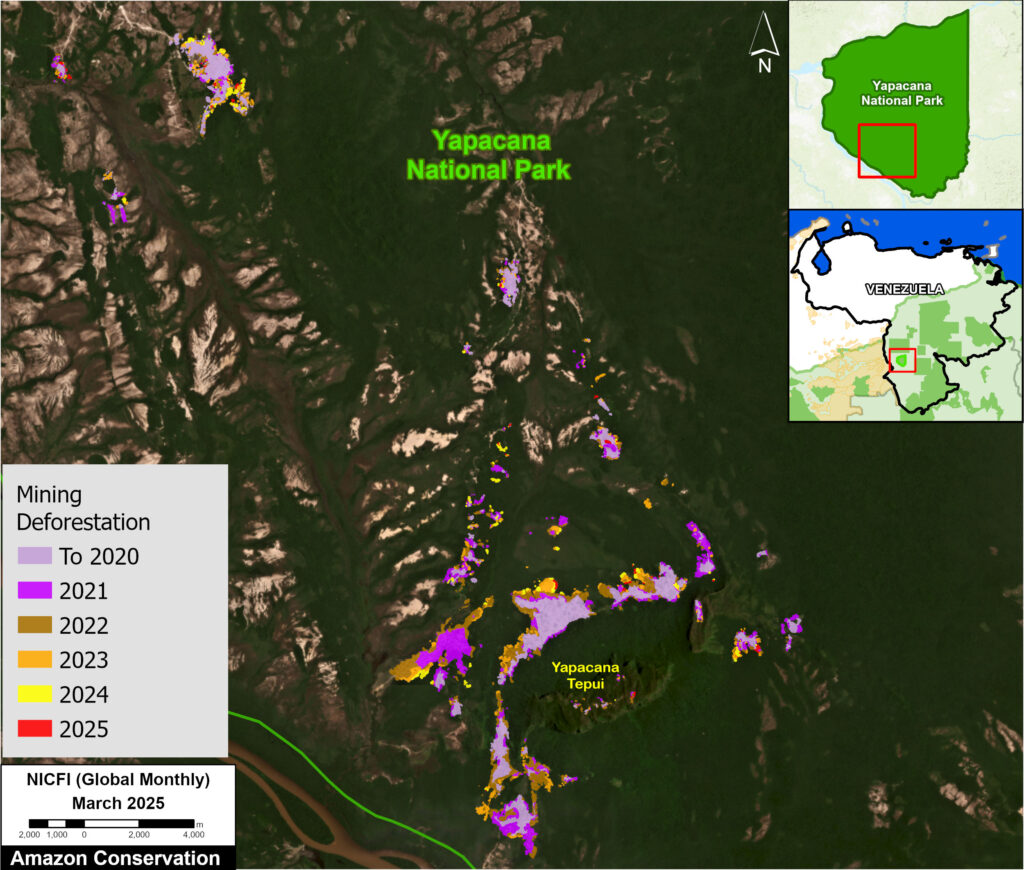

We also show continuing mining deforestation surrounding the tepui in other parts of Yapacana National Park. As of the time of the government intervention in late 2022, we detected the cumulative mining deforestation of 2,190 hectares in the park, including large increases in both 2021 and 2022 (MAAP #173). This mining deforestation has slowed, particularly in 2024 and 2025, but has now impacted 2,240 hectares in the park.

Gold Mining Deforestation in Yapacana National Park, 2020-2025

Figure 1 presents our digitized results for annual mining deforestation across all mining areas in Yapacana National Park, based on an analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery.

Figure 1 presents our digitized results for annual mining deforestation across all mining areas in Yapacana National Park, based on an analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery.

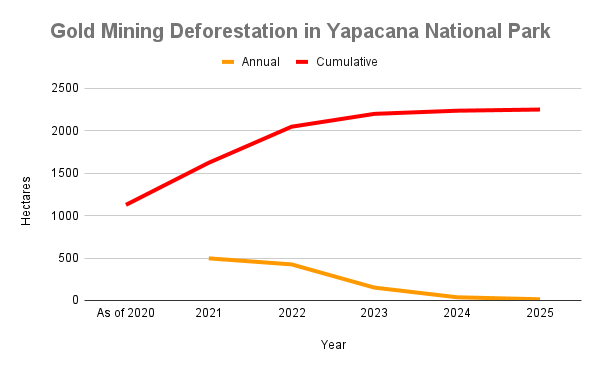

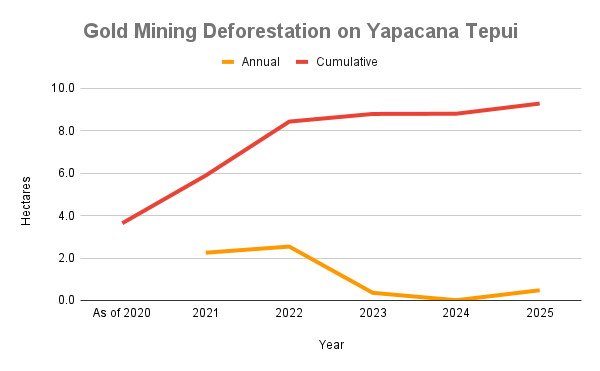

Graph 1 shows the trends found in the digitized data of Yapacana National Park.

The orange line shows the annual mining deforestation decreasing following the highs detected in 2021 and 2022. Both years had over 400 hectares of new mining deforestation, while 2024 had just 37 hectares.

The red line shows the cumulative mining deforestation rising from the baseline in 2020 before plateauing in 2024 and 2025, with a current deforestation total of 2,250 hectares.

Gold Mining Deforestation on top of Yapacana Tepui, 2020-2025

Figure 2 presents our digitized results for annual mining deforestation on top of the Yapacana Tepui, based on an analysis of high-resolution satellite imagery.

Graph 2 shows the trends found in the digitized data on top of Yapacana Tepui.

The orange line shows the annual mining deforestation of about 2 hectares in both 2021 and 2022, followed by a notable decrease after the government intervention in late 2022. In fact, there was zero detected mining deforestation in 2024, followed by the reappearance detailed in this report.

The red line shows the cumulative mining deforestation rising from the baseline in 2020 before plateauing in 2024 and 2025, with a current deforestation total of 9.3 hectares.

Recent Gold Mining Deforestation Events, 2024-2025

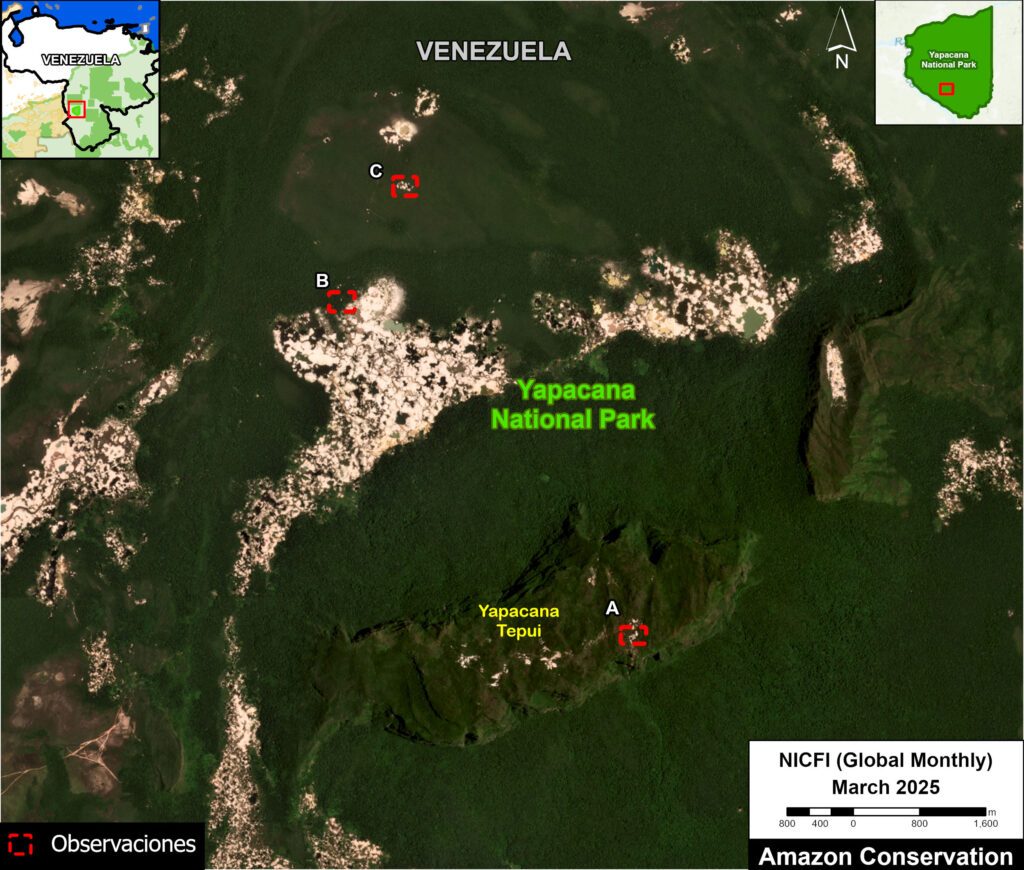

In the Base Map, Insets A-C indicate the three areas with documented gold mining expansion between 2024 and 2025, based on an analysis of very high-resolution satellite imagery.

Below, we provide a more detailed examination of these three areas.

Illegal gold mining on top of the Yapacana Tepui

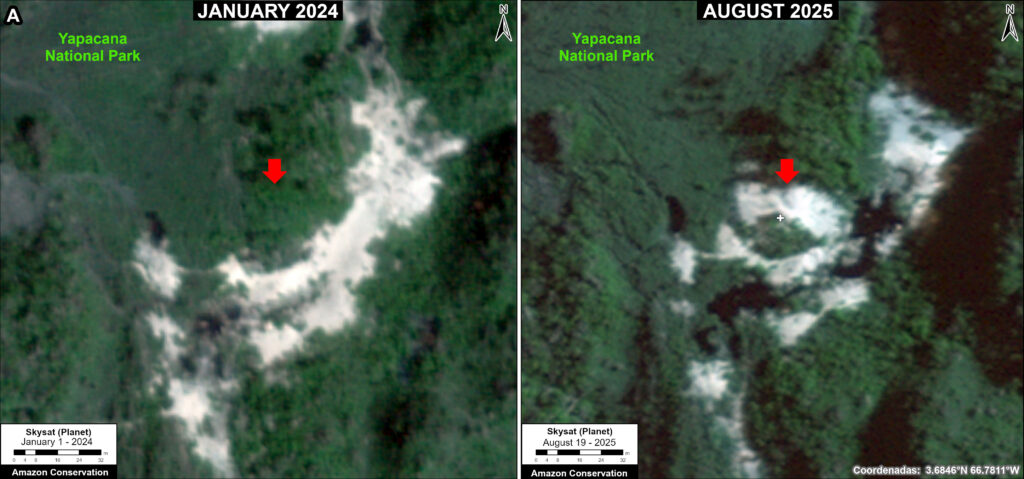

Zoom A shows the recent gold mining deforestation of 0.09 hectares between January 2024 (left panel) and August 2025 (right panel), located on the top of the Yapacana Tepui in Yapacana National Park. Although a small expansion, it indicates the return of illegal mining on the tepui.

Illegal gold mining in Yapacana National Park

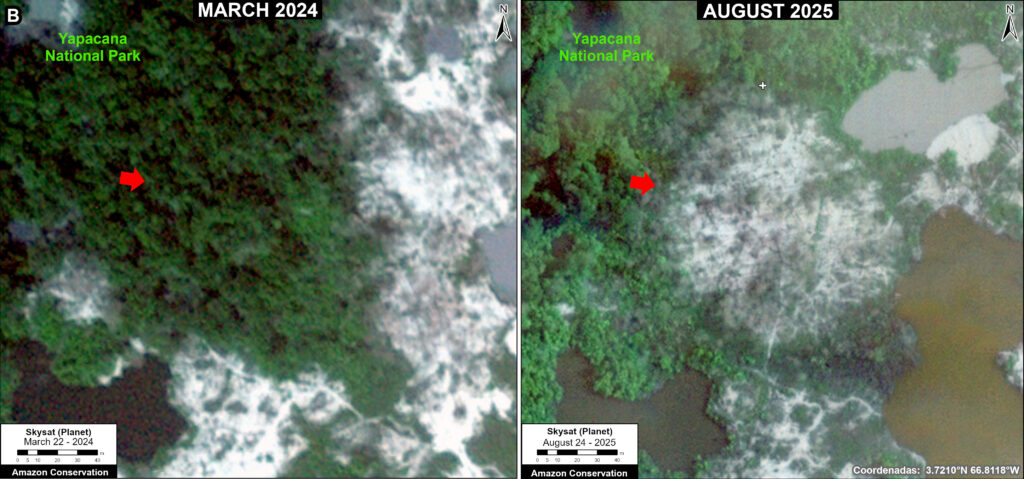

Zoom B shows the recent gold mining deforestation of 22.4 hectares between March 2024 (left panel) and August 2025 (right panel) in Yapacana National Park, just to the north of the Yapacana Tepui. There are also signs of mining equipment associated with this activity.

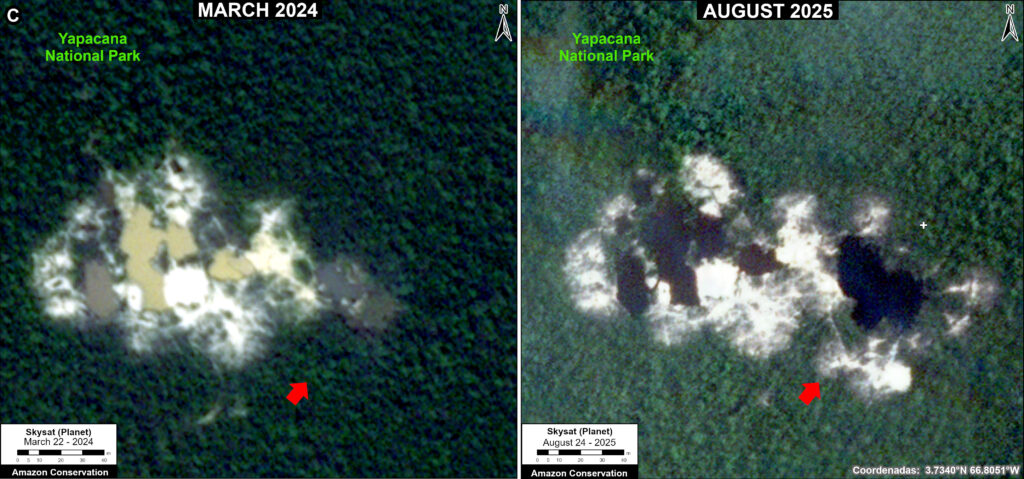

Zoom C shows the recent gold mining deforestation of 1.01 hectares between March 2024 (left panel) and August 2025 (right panel) in Yapacana National Park, just to the north of the Yapacana Tepui.

Policy Implications:

Mining is strictly prohibited in all Venezuelan national parks. This legal protection is fundamental to the conservation of the country’s most biodiverse and ecologically significant areas.

In addition, mining is explicitly prohibited in Amazonas (state in which Yapacana National Park is located) by Presidential Decree No. 269 (1989). This decree was enacted to safeguard the unique ecosystems and indigenous territories of the region, recognizing their global and national importance.

To enforce these legal prohibitions, there is a permanent command post of the Bolivarian National Guard at the entrance of Yapacana National Park. The presence of this security force raises important questions about the effectiveness and willingness of law enforcement and the actual control over activities within the park.

Although the recent mining deforestation on top of the Yapacana Tepui in 2025 is quantitatively small (0.09 hectares), it highlights the importance of early detection and response, especially in such ecologically and culturally sensitive zones. The fact that this renewed activity occurs in the presence of a permanent National Guard command post raises serious concerns about the effectiveness of enforcement and the real capacity of the state to prevent illegal operations. It also suggests that even minimal incursions should not be dismissed, as they may signal the beginning of a new cycle of degradation.

Fuel distribution in the region is officially managed by PDVSA (the state oil company) under strict military supervision. However, given Amazonas’ status as a border state with Colombia and Brazil, gasoline may also be sourced from one of them, most likely Colombia, due to its proximity. The transport of fuel—whether Venezuelan or Colombian—requires the use of boats or helicopters, both of which are highly visible and subject to monitoring by the Bolivarian National Armed Forces. This context places the Armed Forces at the center of the logistical dynamics that either enable or prevent illegal mining, as both aerial control and fuel supply are essential for mining operations.

These facts invite us to reflect critically on the disconnect between legal frameworks and on-the-ground realities. How is it possible that illegal mining persists and even expands in areas with such clear legal protection and a strong security presence? What are the implications for conservation, indigenous rights, and the rule of law? The answers to these questions are crucial for understanding the challenges facing protected areas in Venezuela and for designing more effective strategies to address them.

This entire situation highlights the need to establish mechanisms to monitor illegal gold trafficking, both at its exit points outside the country and on the routes to the markets where the gold is refined and sold.

Biodiversity impacts:

Yapacana Tepui (Cerro Yapacana), a sandstone mountain rising to 1,345 meters above sea level in the southwestern quadrant of Yapacana National Park (PNY), is a geomorphologically and ecologically unique formation within the Venezuelan Amazon. The park encompasses a mosaic of landscapes, including alluvial plains, erosion-alteration peneplains, and nutrient-poor white sand savannas, which host highly specialized vegetation with floristic links to both the Paleotropics and Neotropics. The mountain itself supports two distinct montane forest types—submontane evergreen forests on its slopes and cloud forests on its summit—harboring at least eight critically endangered endemic plant species. These ecosystems are part of the ancestral territory of Arawako, Huottüja (Piaroa), and Mako peoples, who regard the tepui as sacred (MARNR-ORSTOM 1988; Castillo y Salas 2007; SOSOrinoco 2019).

Illegal gold mining has emerged as a major threat to the integrity of these ecosystems, particularly on the summit of Cerro Yapacana, where deforestation from mining camps and machinery has directly impacted the fragile forest habitat. The destruction of summit vegetation not only endangers endemic flora but also disrupts ecological processes vital to the survival of species such as the Yapacana antbird (Myrmeciza disjuncta) and the red Yapacana frog (Minyobates steyermarki), both of which are exclusive to this tepui. Mining-induced deforestation across the park has reached over 2,240 hectares, threatening the continuity of forest cover, savannas and the ecological connectivity essential for species migration and resilience (Huber 1995; Llamozas et al., 2003; Lentino, 2006; Señaris and Rivas, 2006).

The broader biodiversity of Yapacana National Park is also at risk, including its designation as an Important Bird Area (IBA) due to the presence of species such as Crax alector, Selenidera nattereri, and migratory birds like Dendroica striata. The park hosts over 260 bird species, alongside 51 reptiles and 29 amphibians (Lentino, 2006; Señaris and Rivas, 2006). The illegal mining not only degrades these habitats but also introduces pollutants and human disturbance, undermining conservation efforts and threatening the survival of species with restricted ranges and specialized ecological requirements. Urgent and sustained action is needed to halt further degradation and safeguard the exceptional biodiversity of Cerro Yapacana and its surrounding ecosystems (SOSOrinoco, 2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the organization SOSOrinoco for important information and comments related to this report.

This report is part of a series focusing on gold mining in the Amazon, with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

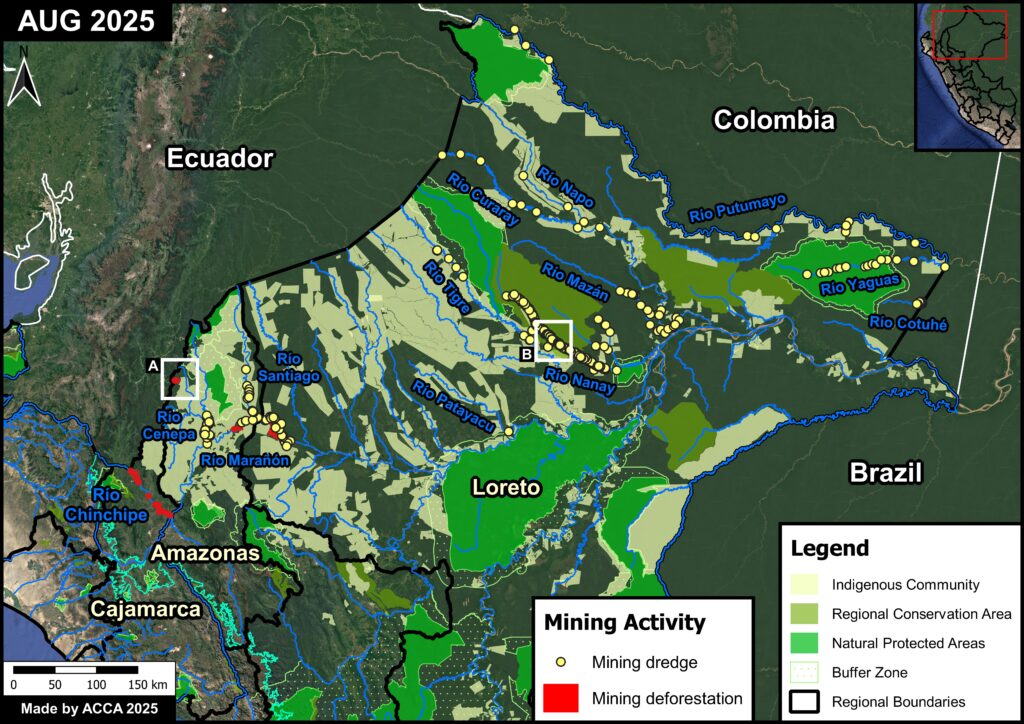

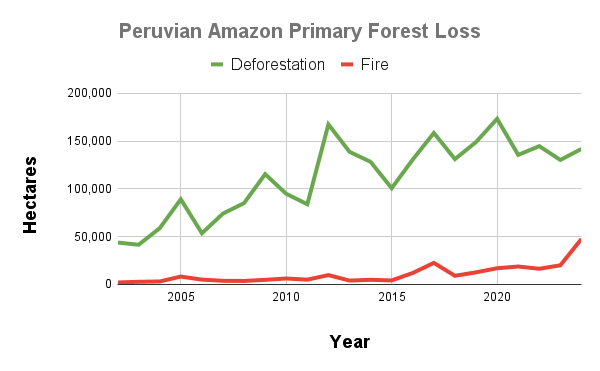

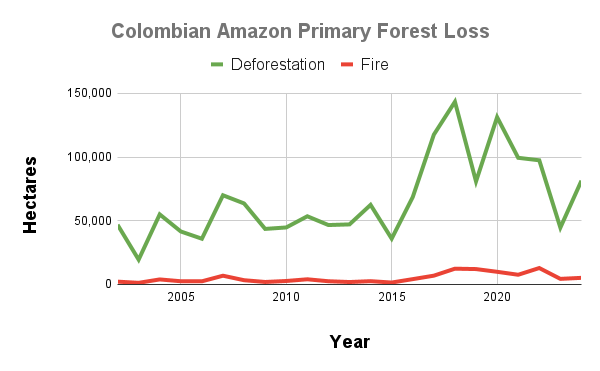

MAAP #233: Current situation of gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon

Gold mining continues to increase in the Peruvian Amazon. Following the initial success of the major multisectoral government intervention Operation Mercury in southern Peru in early 2019 (MAAP #104, MAAP #121, MAAP #130), the illegal mining activity rebounded during the COVID-19 pandemic, as the government withdrew from the area (Vadillo, 2022).

The current increase, directly linked to soaring international gold prices, has led to expanding mining activity: continuing mining in southern Peru, and emerging mining fronts in the central and northern parts of the country.

This report presents information on the current state of gold mining activity, in both forests and rivers, across all of the Peruvian Amazon.

Notably, we report that gold mining has spread to nine regions across the Peruvian Amazon: Amazonas, Cajamarca, Cusco, Huánuco, Loreto, Madre de Dios, Pasco, Puno, and Ucayali.

Total gold mining deforestation has reached 139,169 hectares (343,894 acres) as of mid-2025, the vast majority (97.5%) in the Madre de Dios region of southern Peru. The Huánuco and Puno regions have also experienced rising mining deforestation (1,262 and 1,014 hectares, respectively).

Moreover, alluvial gold mining is also expanding in numerous rivers across the Peruvian Amazon, especially in the northern regions of Loreto and Amazonas. We have identified 989 mining dredges in Loreto since 2017, followed by 174 in Amazonas.

Overall, we have documented gold mining activity in 225 water bodies (rivers and streams) across the Peruvian Amazon.

Below, we present the detailed results of this report in three regional sections: northern Peru (Amazonas, Cajamarca, and Loreto); central Peru (Huánuco, Pasco, and Ucayali); and southern Peru (Cusco, Madre de Dios, and Puno). Each section presents information about mining in forests (deforestation) and rivers.

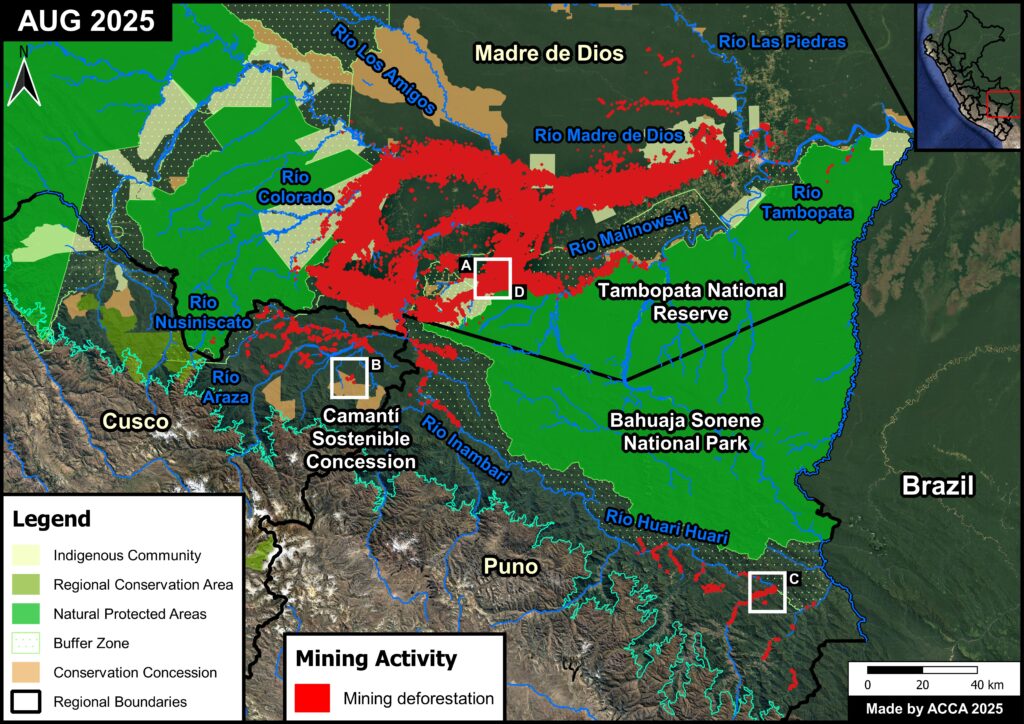

Base Map. Data: ACA, ACCA, CINCIA, FEMA, SZF, IBC, SERNANP, Mapbiomas Perú

Northern Peru

Gold mining has spread to both the forests and rivers of Amazonas, Cajamarca, and Loreto regions of the northern Peruvian Amazon (Figure 1).

Gold mining deforestation has impacted 491 hectares, located near rivers and within Indigenous communities (see red areas in Figure 1). The mining deforestation has been localized along the Chinchipe River in Cajamarca, and near the Marañón River in Amazonas and Loreto.

We highlight the recent mining deforestation along the Sawintsa River near the Peru-Ecuador border in the Amazonas and Cajamarca regions (Figura 1A).

In addition, river-based mining has emerged as a critical issue in northern Peru, where we have documented mining barges in at least 14 rivers (see yellow dots in Figure 1).

Loreto is the most impacted region, where we have documented 989 mining dredges between 2017 and 2025.

The Nanay River, located in Loreto, is the most impacted by mining dredges Figure 1B. We have identified 841 mining dredges since 2017, including 275 in 2025. This mining activity extends into Indigenous communities and the Alto Nanay – Pintuyacu – Chambira Regional Conservation Area.

Mining also impacts the Cenepa and Santiago Rivers, located in Amazonas. We have identified 137 and 51 mining dredges, respectively, in these rivers since 2022. Some of this mining activity surrounds Indigenous communities in Amazonas.

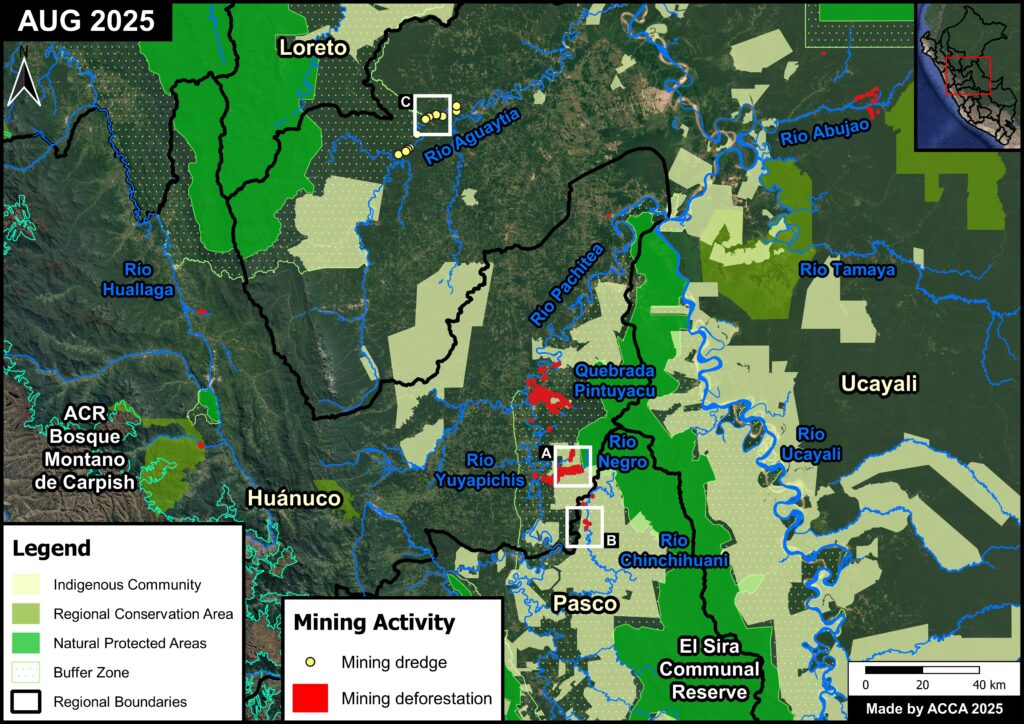

Central Peru

Gold mining also impacts both the forests and rivers of Huánuco, Pasco and Ucayali regions in the central Peruvian Amazon (Figure 2).

Gold mining deforestation has reached 1,320 hectares, located along rivers, in Indigenous communities, in the Carpish Montane Forest Regional Conservation Area, and in the buffer zone of the El Sira Communal Reserve (see red areas in Figure 2).

The Huánuco region is the most impacted by mining deforestation in central Peru, with the vast majority (97%) occurring in the province of Puerto Inca (Figure 2A).

In the Pasco region, gold mining deforestation has been recorded in pending mining concessions along the Chinchihuani River since August 2024 (Figure 2B).

Gold mining in the Ucayali region has been located along the Abujao River.

In addition, river-based mining is impacting the Aguaytía River, in the Ucayali region (see yellow dots in Figure 2).

We first detected mining dredges in mid-2024 (Figure 2C) in this area, located near the buffer zone of Cordillera Azul National Park.

In total, we have identified 26 mining dredges in the Aguaytía River in 2024 and 2025.

Southern Peru

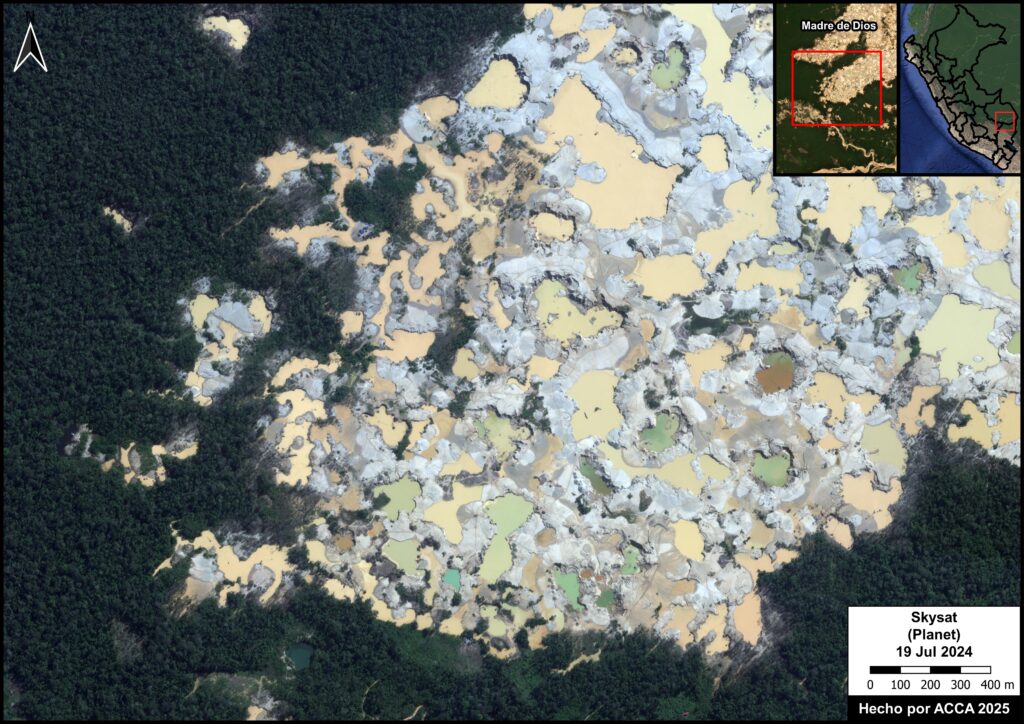

Gold mining deforestation has had major impacts in the regions of Cusco, Madre de Dios, and Puno, in the southern Peruvian Amazon. Note in Figure 3 that mining deforestation (indicated in red) is the dominant impact, and not mining barges as seen in the northern Peruvian Amazon.

We have documented the gold mining deforestation of 137,558 hectares (339,913 acres) in these southern regions, accounting for 98.7% of total mining deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon. This massive gold mining deforestation started in 1984 in Madre de Dios.

Madre de Dios has the highest gold mining deforestation of all the regions in Peru (135,939 hectares), accounting for 97.5% of the national total.

This widespread mining deforestation in Madre de Dios has extended into Indigenous communities and the buffer zones of protected areas, such as Tambopata National Reserve (Figure 3A) and Amarakaeri Communal Reserve.

In the Cusco region, gold mining deforestation has spread to various areas around the Araza and Nusiniscato Rivers.

Además, parte de la deforestación por minería se ha extendido al interior de la zona de amortiguamiento de la Reserva Comunal Amarakaeri y en la Concesión para Conservación Camanti Sostenible (Figura 3b).

The Puno region has experienced gold mining deforestation near the Inambari and Huari Huari Rivers (Figure 3C), surrounding the buffer zone of the Bahuaja Sonene National Park.

In Madre de Dios, we have detected over 2,000 pieces of mining infrastructure, such as drills, chutes, dredges, and mining rafts (Figure 3D) (ACCA, 2022).

Policy recommendations for gold mining in Peru:

Gold mining in Peru represents one of the country’s greatest socio-environmental challenges, impacting Amazonian forests, rivers, and local communities (Arana Cardó, M, 2024). In response, we present five policy proposals aimed at minimizing this impact, focusing on 1) implementing gold traceability, 2) strengthening the Artisanal and Small-scale mining (ASM) Law, 3) establishing environmental obligations, 4) strengthening supervision, and 5) promoting clean technologies (including banning mercury).

1. Implement an effective gold traceability system that links production, marketing, and export

Currently, the Special Registry of Gold Traders and Processors, created by Ministerial Resolution No. 249-2012-MEM-DM, lacks effective mechanisms for cross-referencing information.

Therefore, it is recommended to consolidate a comprehensive traceability system that covers not only producers, traders, processors, and exporters, including the jewelry industry, but also the control of critical inputs such as mercury and fuels, in order to guarantee supply chains free of contamination and illegal activities.

This system must integrate real-time digital controls, cross-reference information between what is declared as production and what is actually traded, prevent the illegal export of gold in the form of jewelry, and align with international due diligence requirements.

2. Strengthening the Artisanal and Small-scale mining (ASM) Law & improving the formalizatin registry (REINFO)

Regulations on small-scale and artisanal mining should establish clear categories based on production and technology, differentiating the formalization process (aimed at pre-existing informal miners and includes phased-in measures and technical support) from the ordinary permitting process, which requires full compliance with environmental and technical requirements for new projects.

The new law for Artisanal and Small-scale mining (ASM) should incorporate real incentives for formalization and the adoption of sustainable practices, effective oversight mechanisms, and the delimitation of exclusive zones for formalized activity, excluding natural Protected Areas, Indigenous reserves, bodies of water, and cultural heritage sites.

Additionally, this new regulation must establish mandatory due diligence throughout the gold value chain, linking the formalization process to the implementation of a traceability system. Thus, formalized miners must not only comply with basic legal requirements but also ensure that their production is free of illegal inputs such as mercury, meeting international standards of transparency and sustainability.

Likewise, given the formalization extension granted until December 31, 2025, in Supreme Decree No. 012-2025-EM, it is essential that the government improve the Comprehensive Registry of Mining Formalization (REINFO in Spanish), permanently removing those who do not meet the minimum requirements established in Law No. 32213 and its regulations, as indicated by its update through Supreme Decree No. 009-2025-EM. Furthermore, proportional sanctioning mechanisms must be evaluated to discourage the misuse of the registry. Only in this way will it be possible to prevent this registry from continuing to be used as a shield of impunity against the actions of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the National Police, and to ensure that formalization translates into an effective change in mining practices.

3. Establish environmental obligations from the beginning of mining formalization & ensure their supervision

Regulations should establish that all small-scale and artisanal mining activities must be subject to the respective environmental obligations from the initial formalization process, in order to ensure early and effective oversight.

During this process, operations must be subject to governmental oversight by the Environmental Assessment and Oversight Agency (OEFA in Spanish), the Supervising Agency for Investment in Energy and Mining (OSINERGMIN in Spanish), and the National Superintendence of Labor Inspection (SUNAFIL in Spanish). Likewise, administrative and criminal sanctions must be applied to responsible authorities who fail to fulfill their oversight duties.

Additionally, forest zoning should be promoted and advanced, in accordance with the provisions of the Forestry Law (Law No. 29763), with an emphasis on the Amazon regions of Peru. This should be integrated into the mining formalization process and become a formal requirement for granting permits. The integration of zoning will prevent the granting of new permits in priority forests for conservation, reducing deforestation and misuse of forests by directing mining toward areas of lower impact and prohibiting it in critical areas. This would require mining formalization authorities to consult zoning maps from the outset. That is, applicants must include the forest zoning category of their plot and demonstrate compatibility before issuing a permit.

4. Strengthen ASM supervision at the regional level through inter-institutional agreements

We propose the signing of agreements between OEFA and the Amazonian regional governments, accompanied by technical support and technological equipment for real-time monitoring of operations in remote areas.

Furthermore, following the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) guidelines, the formation of specialized multidisciplinary teams to support field supervision is recommended, helping to close capacity gaps and ensure the effectiveness of environmental monitoring in critical territories.

5. Promote clean technologies and ban the use of mercury by 2030.

In compliance with the Minamata Convention, Peru must adopt a policy to phase out mercury in gold mining.

To this end, it is recommended that miners be facilitated access to clean technologies through loans, subsidies, or tax benefits, ensuring safer processes for the environment and public health, so that the technological transition increases gold recovery and reduces impacts on rivers and local communities.

However, this policy must be accompanied by specific goals for the protection of forest resources, as well as stricter sanctions for those who continue to use mercury and generate deforestation, thus ensuring true environmental and public health protection. Furthermore, these goals must be expressly incorporated into the Minamata Convention’s National Action Plan, ensuring its effective and coordinated implementation throughout the country.

Methodology

The identification of gold mining deforestation in Peru was based on the visual interpretation of high- and very high-resolution satellite imagery available on Planet, Maxar, and Google Earth Pro for the regions of Amazonas, Cajamarca, Cusco, Huánuco, Loreto, Pasco, Puno, and Ucayali. We conducted a preliminary review of maps and platforms related to mining detection in Peru (the Early Detection and Environmental Monitoring System of the Peruvian Ministry of the Environment, Amazon Mining Watch, and Mapbiomas Perú) to locate potential mining areas. In addition, we compiled reports and newspaper articles related to gold mining in different regions of the country to identify mining areas, as well as direct communications from representatives of different institutions regarding signs of mining activity at the local level. Based on these preliminary processes, we identified gold mining deforestation using satellite imagery. Additionally, we conducted monitoring of mining-related deforestation using monthly Planet NICFI mosaics (4.7 m spatial resolution) to track the expansion of mining-related deforestation and identify new nearby mining areas.

The identification of gold mining deforestation in Madre de Dios used historical mining deforestation information generated by the Amazon Scientific Innovation Center (CINCIA) for the years 1984 – 2019, by Mapbiomas Perú for the year 2020, and by Amazon Conservation (ACA) for the period January 2021 – March 2024. Then, we used the LandTrendR algorithm to identify forest loss in monthly mosaics of Planet NICFI for the period April 2024 – July 2025. Subsequently, we conducted a manual review to identify forest loss resulting from gold mining and other causes.

The identification of river-based mining was based on the visual interpretation of very high-resolution satellite imagery available on Planet, Maxar, and Google Earth Pro for various Amazonian rivers and mining areas in Peru. In addition, confidential reports and direct communications from various institutions regarding the presence of mining infrastructure in Amazonian rivers were included.

References

Arana Cardó, M. (2024). Minería ilegal en la Amazonía peruana: Informe sobre las actividades mineras en las regiones amazónicas de Loreto, San Martín, Amazonas, Ucayali, Madre de Dios y Huánuco. Fundación para la Conservación y el Desarrollo Sostenible Perú (FCDS). https://fcds.org.pe/wpcontent/uploads/2024/07/Resumen_Ejecutivo_informe_mineria_compressed-1.pdf

Conservación Amazónica (ACCA), Proyecto Prevenir – USAID. (2022). Estimación de la población minera informal e ilegal en el departamento de Madre de Dios, a partir del uso de imágenes satelitales sub métricas. https://repositorio.profonanpe.org.pe/handle/20.500.14150/2744

Delfino, E. (20 de julio de 2025). Minería ilegal en Perú: “Hay una presión internacional por el oro y los principales países consumidores no realizan una debida diligencia respecto al origen” | ENTREVISTA. Mongabay. https://es.mongabay.com/2025/07/mineria-ilegal-peru-oro-amazonia-contaminacion/

OCDE (2016). OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas: Third Edition. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264252479-en.

Vadillo Vila, J. (2022). La minería ilegal y su impacto en tiempos de pandemia. Diario El Peruano. https://elperuano.pe/noticia/170967-la-mineria-ilegal-hoy

Zapata Perez, M., Arana Cardo, M., Ramires Valle, D., Castro Sánchez-Moreno, M., Garay Tapia, K., Rivadeneyra Tello, G., Vega Ruiz, C. y Cabanillas Vasquez, F. (2025). 10 propuestas para la formalización efectiva de la pequeña minería y minería artesanal. Observatorio de Minería Ilegal. https://www.observatoriomineriailegal.org.pe/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/10_propuestas_ley_MAPE_020525.pdf

Citation

Pacsi R, Novoa S, Yupanqui O, Quispe M, La Torre S, Balbuena H, Huamán B, Valdivia G, Castañeda C, Soria M, Finer M, Santana A (2025) Current situation of gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon. MAAP: 233.

Acknowledgments

This report is part of a series focusing on gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon, through a strategic collaboration between Amazon Conservation and Conservación Amazónica – Peru (ACCA), with support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

MAAP #232: The Amazon Tipping Point – Importance of Flying Rivers Connecting the Amazon

The Amazon biome, stretching over a vast area across nine countries in northern South America, is renowned for its extreme diversity (biological and cultural) and its abundant water resources. Indeed, the major features of the Amazon are linked by interconnected water flows, both on land and in the air (Beveridge et al. 2024).

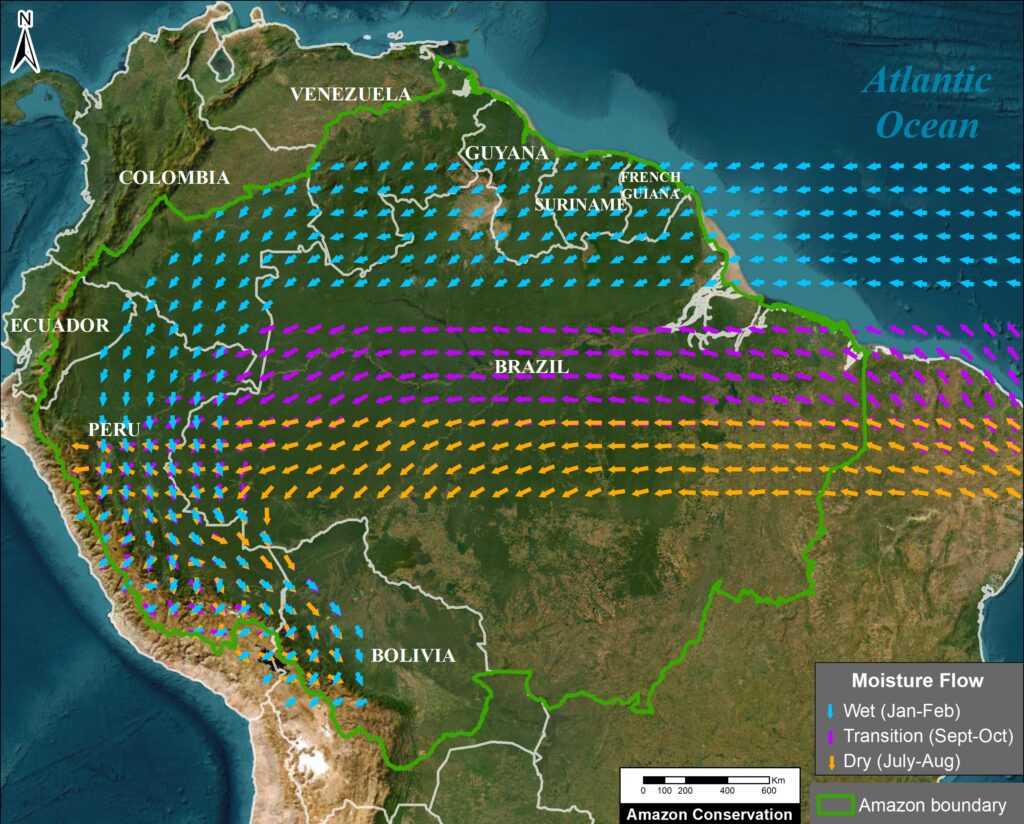

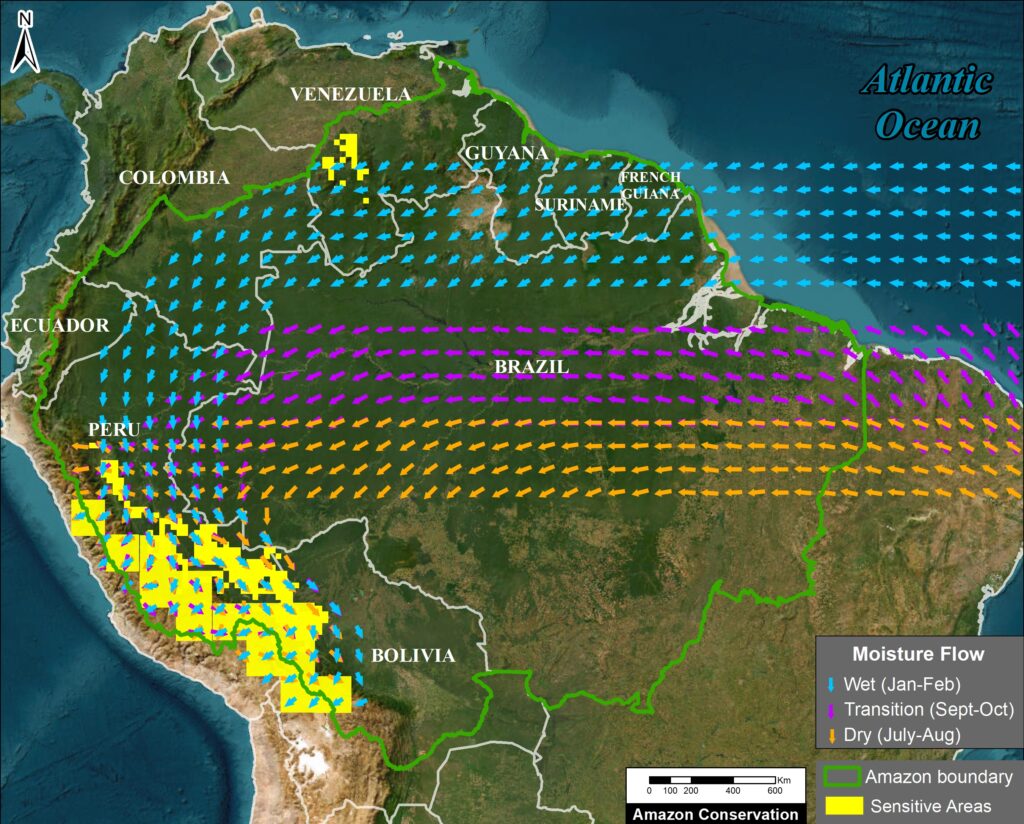

The natural phenomenon of aerial moisture transport and recycling, also known as “aerial rivers” and popularized in the press as “flying rivers,” has emerged as an essential concept related to the conservation of the Amazon. In short, moisture flows from the Atlantic Ocean across the Amazon, uniquely facilitated by the rainforest itself. As they move westward, these flying rivers drop water onto the forest below. The forest subsequently transpires moisture back into them, thus recycling water and supporting rainforest ecosystems far from the Ocean source. For example, the Intro Map illustrates the aerial river for the southwest Amazon.

Continued deforestation and forest degradation, however, will disrupt and diminish the critical east-to-west aerial water flow, inducing a “tipping point” of impacted regions that would transition from rainforest to drier savannah ecosystems.

In this report, we aim to both summarize the current state of knowledge on the movement of atmospheric moisture across the Amazon and develop novel analyses based on this information. Overall, we aim to show the critical connections between the eastern and western Amazon, and how these connections change during the major seasons (wet, dry, and transition) of the year.

Our analysis is divided into three main parts:

First, we summarize the state of knowledge on the movement of atmospheric moisture across the Amazon, drawing on a review of recent literature and exchanges with experts. Second, we identify the sensitive areas that are the most vulnerable to deforestation-caused disruption of moisture recycling. Third, we relate these sensitive areas in the west to their respective eastern key source areas for moisture for each of the three Amazonian seasons: wet, dry, and transition.

In summary, we identified the sensitive areas that are the most vulnerable to deforestation-caused disruption of moisture recycling from the Atlantic Ocean source are mostly located in the southwestern Amazon (Peru and Bolivia). For the wet season, much of the moisture flow to these sensitive areas crosses the continuous primary (non-deforested) forests of the northern Amazon. For the dry and transition seasons, however, the moisture flow to the sensitive areas must cross several major deforestation fronts located in the eastern Brazilian Amazon.

Thus, an important contribution of this work is to reveal that, contrary to the common perception that the tipping point is a single Amazon-wide event, certain parts of the Amazon are more vulnerable than others. Most notably, the southwestern Amazon (Peru and Bolivia) is most vulnerable to a possible tipping point, particularly stressed by disrupted dry season moisture flows over major deforestation fronts.

1. Movement of aerial moisture across the Amazon (moisture flow)

Driven by permanent trade winds, aerial (atmospheric) moisture flows westward from its source in the Atlantic Ocean, across the Amazon lowlands, and toward the Andes Mountains. These moisture routes are recharged by evapotranspiration and discharged by precipitation, creating moisture recycling systems (Beveridge 2024, Weng et al. 2018, Staal 2018, Weng 2019). Evaporation recycling reloads atmospheric moisture after rainfall, while precipitation recycling removes this moisture. The Amazon forest is therefore a key component of a giant water pump, starting with water transported from the tropical Atlantic Ocean and helping push it westward (Zemp 2017, Boers 2017). Aerial rivers are the long-term and large-scale preferential pathways of the moisture flows driving this pump (Arraut et al. 2012) (see Intro Image). Thus, aerial rivers are the overall average (coarse-scale) moisture flow pattern, while moisture recycling focuses more on the seasonal differences (finer-scale).

Of all the rainfall in the Amazon, its trees have directly transpired 20% of it (Staal et al. 2018). Half of this precipitation (10%) is from moisture from one recycling event, and the other half (10%) is from multiple recycling events. This latter process of cascading precipitation, or cascading moisture recycling (Zemp et al. 2014), may happen multiple times (up to five or six), recycling water from the eastern to western Amazon, to areas increasingly distant from the Atlantic Ocean source (Lovejoy and Nobre 2019, Beveridge et al, 2024). Precipitation tends to increase exponentially as moist air travels over forests, but then drops off sharply once it moves beyond them, showing just how vital forests are in sustaining rainfall across large regions (Molina et al. 2019). Transpiration-driven moisture recycling is especially important during the dry season (Staal et al. 2018, Nehemy et al. 2025).

Thus, there are transboundary implications, as actions occurring in an eastern country can have an impact on a western country downwind of the moisture cascade. For example, deforestation in eastern Brazil can negatively impact moisture flow going to Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, including the tropical Andean mountains (Ruiz-Vasquez et al., 2020; Sierra et al. 2022, Flores et al 2024). As moisture recycling also continues beyond the boundaries of the Amazon, there may also be impacts to agricultural areas in southern Brazil, Paraguay, northern Argentina, and northern Colombia (Martinez and Dominguez 2014; Ruiz-Vasquez et al., 2020).

The resulting terrestrial flow of water from the Andes mountains through the Amazon lowlands and back to the Atlantic Ocean as runoff and flow of the Amazon river and its tributaries results in the emerging concept known as the “Andes–Amazon– Atlantic” (AAA) pathway (Beveridge et al, 2024).

Importantly, the moisture flows change seasonally in the Amazon. Figure 1 illustrates these seasonal changes for the southwest Amazon, as an example.

In the rainy season (January–February), the moisture flow is both westward and southward, creating a giant arc (Arraut 2012). Thus, the continental moisture source is the northeast Amazon (Boers 2017, Weng et al. 2018, Sierra et al. 2022).

In the dry (July–August) and the dry-to-wet transition (September-October) seasons, the moisture flow shifts more directly westward (Arraut 2012, Staal et al, 2018). Therefore, the continental moisture source is the southeast Amazon, and some studies have identified this region as the most important for maintaining overall Amazonian resilience (Zemp et al. 2017, Staal et al. 2018).

There is increasing evidence that future deforestation will reduce rainfall downwind – further west – of the moisture recycling networks, inducing a “tipping point” of impacted regions that would transition from rainforest to savannah ecosystems (Boers 2017, Staal 2018, Lovejoy & Nobre 2018). This has led to calls for forest protection strategies to maintain the cascading moisture recycling system fueling the pathway (Zemp 2017, Encalada et al. 2021). A recent review indicates limited evidence for a single, system-wide tipping point; instead, specific areas of the Amazon may be more vulnerable (Brando et al, 2025).

Scientists are already documenting impacts linked to increasing forest loss. Several recent studies have found that Amazon deforestation has already caused a significant decrease in precipitation in the southeast Amazon, particularly during the dry season (Qin et al, 2025, Liu et al, 2025, Franco et al. 2025). Moreover, deforestation reduces rainfall upwind of the cleared areas, impacting the western Amazon as well (Qin et al, 2025). In addition, recent studies have shown that Amazon deforestation delays the onset of the wet season in southern Amazonia (Ruiz-Vasquez et al., 2020; Commar et al., 2023; Sierra et al., 2023).

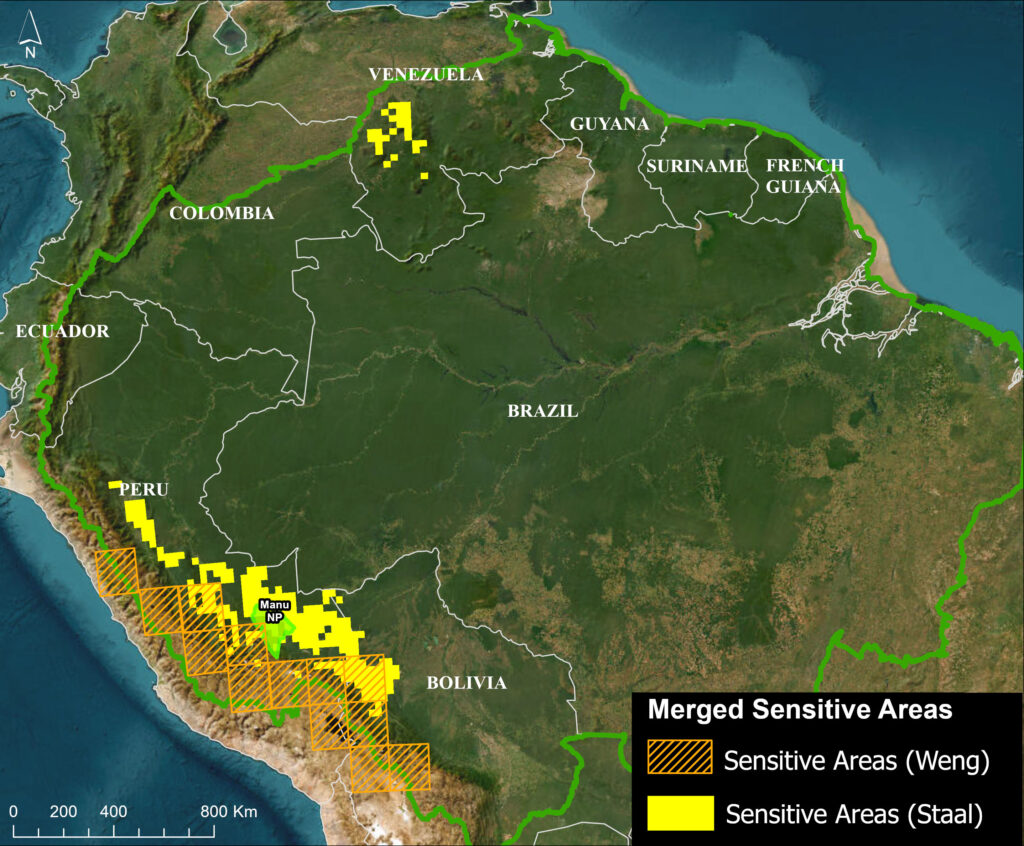

2. Areas most dependent on moisture recycling in the Amazon (sensitive areas)

A series of recent empirical and modeling studies indicate that the southwest Amazon (including the Peruvian and Bolivian ranges of the tropical Andes) is the major moisture sink – the area where precipitation is most dependent on moisture recycling (Boers et al. 2017, Zemp et al. 2017, Weng et al. 2018, Staal et al. 2018, Sierra et al. 2022). In fact, tree-transpired rainfall is greater than 70% in this region (Staal et al. 2018, Weng et al. 2018).

Given its dependence on transpiration-driven precipitation, the impact of a reduction in rainfall from cascading moisture recycling is predicted to be greatest in the southwest Amazon (Zemp et al. 2017, Weng et al. 2018, Staal 2018, Sierra et al. 2022, Beveridge 2024). Indeed, the southwest Amazon forest may enter the bioclimatic equilibrium of savannas following projected extensive Amazon deforestation scenarios (Zemp, 2017). Forests in the northwest and Guyana Shield are also relatively dependent on forest-rainfall cascades (Hoyos et al 2018; Staal et al. 2018).

To precisely identify the most vulnerable areas in the Amazon to disruptions of transpiration-based moisture recycling in a spatially explicit manner, we merged two key studies featuring spatially explicit model outputs (Weng 2018, Staal 2018). These studies cover data for the dry season (Staal 2018) and yearly (both dry and wet seasons) (Weng 2018).

Weng 2018 identifies “sensitive areas,” defined as areas having more than 50% of rainfall coming from Amazonian evapotranspiration (representing the 98th percentile of the highest sensitivity to Amazonian land use change). Staal 2018 estimates the effect of Amazon tree transpiration on Amazon forest resilience. We selected the areas with the highest resilience loss (0.8 and higher), quantified as the fraction of resilience that would be lost in the absence of tree transpiration by Amazonian trees.

Figure 2 illustrates the merged dataset, which we refer to as “merged sensitive areas.” Notably, both studies concur that the most vulnerable areas are located in the southwest Amazon, spanning the lowlands of only two of the nine countries of the Amazon Basin: Peru and Bolivia. This merged sensitive area covers a 1,750-kilometer-long swath along the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes. In this merged data map, we include Manu National Park as a reference point, located roughly in the middle of the sensitive areas.

Weng et al. identified higher elevation areas of the Andean-Amazon transition area in both Peru (Junín, Cusco, and Puno regions) and Bolivia, while Staal et al (2018) identified slightly lower elevation areas in this same range. These regions are consistent with predicted areas of higher rainfall reduction due to deforestation (Sierra et al. 2022). Also, note that Staal indicates an additional area in the Venezuelan Amazon.

Although, as noted above, forests in the northwest and northeast (Guyana Shield) are also relatively dependent on forest-rainfall cascades, the forests of the southwest are the most dependent, likely given their location at the far end of the Atlantic-Amazon-Andes pathway.

3. Moisture flows to sensitive areas (by season)

Given the reliance of western, especially southwest, Amazon forests on cascading moisture recycling, a key challenge is to identify the most important moisture source areas in the eastern Amazon. In this respect, the literature provides a less definitive answer, likely because the moisture recycling routes change with seasons, in contrast to the long-term path of the aerial rivers that represent overall preferential pathways (Arraut 2012, Staal 2018, Weng et al. 2018).

We correlate the merged sensitive areas in the southwest Amazon with their respective moisture source areas by back-tracking the moisture flows upwind. This component of the work was inspired by the precipitation-shed concept, defined here as the terrestrial upwind surface areas providing evapotranspiration to a specific area’s precipitation (Keys et al. 2012, Weng et al. 2018).

We determined that analyzing all three major seasons is essential because of the major seasonal variability (Staal et al, 2018) and that each plays a key role in the stability of the rainforests: During the wet season, nearly 50% of total annual precipitation falls over the region, and these wet periods recharge Amazonian groundwater reserves vital for sustaining forest transpiration rates during dry months (Miguez-Macho and Fan 2012, Sierra et al 2022). During the dry season, moisture recycling processes are particularly important to ensure that some of the limited precipitation reaches the western Amazon (Beveridge et al, 2024). Tree-transpired rainfall then peaks during September to November, when large parts of the Amazon are at the end of the dry season and transitioning to the wet season (Zanin et al., 2024).

To map the pathway of moisture flow between the western Amazon merged sensitive areas and their eastern moisture sources, we utilize moisture flow data from the ERA5 reanalysis (Hersbach 2023). Specifically, we merged vertically integrated data for both northward and eastward water vapour flux. We chose data from 2022 as a recent year not heavily influenced by extreme weather events such as El Niño or drought (Espinoza et al., 2024). For 2022, we downloaded and analyzed the moisture flow data for three separate time periods: January-February (representing the wet or monsoon season), July-August (dry season), and September-October (dry-to-wet transition season).

The results for all three seasons are illustrated in Figure 3, where the arrows represent the ERA5 reanalysis moisture flow data from the Atlantic Ocean to the merged sensitive areas in the southwest Amazon.

Note that in the wet season (January-February), moisture flows from the Atlantic Ocean over the northeast Amazon (northern Brazil, French Guiana, Suriname, Guyana, and Venezuela) before taking a major southern turn (arc) through the southeast Colombian Amazon and northern Peru before reaching the Sensitive Areas. This general pattern is consistent with other studies focused on the wet season (Arraut 2012, Boers 2017, Sierra et al. 2022) and year-round (Weng et al. 2018).

In contrast, in the dry (July-August) and transition (September-October) seasons, the moisture flows from the Atlantic Ocean further south across the central Brazilian Amazon, and has a less pronounced arc near the border with Peru. Specifically, the dry season pattern is consistent with other studies focused on the dry season (Arraut 2012, Staal 2018, Zemp 2017 NC). Note that the transition season flow is located between the wet season to the north and the dry season to the south.

For all three seasons, we emphasize that the entire trajectory from east to west is important for conservation regarding cascading moisture recycling. That is, the farthest away areas in the east represent the full cascading trajectory, while the closest areas in the west exert the strongest direct influence (Weng et al. 2018).

While moisture recycling covers a vast area from east to west, much of the tree-induced rainfall in the southwest Amazon is transpired nearby (Stall 2018). That is, areas exerting the strongest and most efficient influence on the southwest Amazon are located just upwind, in the central-west Amazon (Weng 2018; Wongchuig et al., 2023). In sum, extensive forest loss anywhere along the cascading moisture pathway from the eastern to the western Amazon, far or near, may affect transpiration-based precipitation in the western Amazon, adding to its sensitivity.

The overall annual pattern, accounting for all three seasons, could then be described as aerial rivers. As indicated by Weng et al. (2018), this mostly matches the pattern of the wet season.

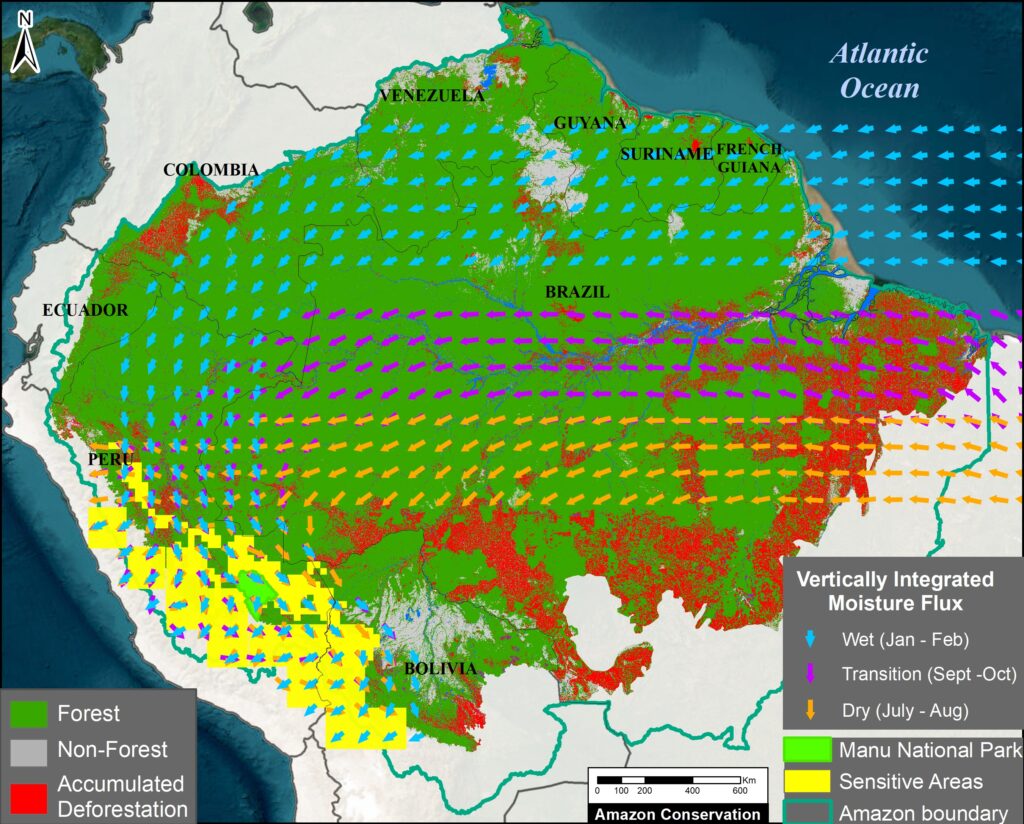

For additional context, Figure 4 incorporates current land classification broken down into three major categories based on satellite imagery analysis: Forest, Non-forest (such as savannah), and accumulated Deforestation areas (as of 2022).

For January-February (wet season), note that much of the moisture flow crosses the continuous primary forest of the northern Amazon. That is, the moisture crosses predominantly non-deforested areas of northern Brazil, French Guiana, Suriname, Guyana, Venezuela, southeast Colombia, and northern Peru.

In contrast, the moisture flows for July-August (dry season) and September-October (transition season) cross several major deforestation fronts in the central Amazon, particularly during the dry season.

During the critical dry-to-wet transition season, the role of the local area’s tree evapotranspiration is especially important. The southern Amazon presents lower overall evapotranspiration values (Fassoni-Andrade 2021; Zanin et al., 2024). Due to the greater access of forest roots to deep soil water, however, evapotranspiration over forested areas is higher than croplands/grasslands during this time (von Randow et al. 2004). Since, during this transition season, the moisture transport to the southwestern Amazon passes over large deforested areas, the conservation of the remaining forest along this pathway is critical.

In addition, recent studies show that the main patterns of moisture flux can be altered at a continental scale due to deforestation (Commar et al., 2023; Sierra et al., 2023). As a result, reduced moisture transport from the Atlantic to the continent and delays in the onset of the wet season may occur in the future due to Amazon deforestation and climate change (Agudelo et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Above, in this initial technical report, we merged three key points that are critical to understanding the tipping point concept in the Amazon.

First, we presented an overview of aerial moisture flows originating from the Atlantic Ocean and then moving and recycling from the eastern to the western Amazon. Second, we identified the “sensitive areas” that are the most vulnerable to deforestation-caused disruption of moisture recycling, mostly located in the western Amazon (Peru and Bolivia). Third, we relate these sensitive areas in the west to their respective eastern key source areas for moisture for each of the three Amazonian seasons: wet, dry, and transition.

Incorporating updated land-use data, we found important differences by season. For the wet season, much of the moisture flow crosses the continuous primary (non-deforested) forests of the northern Amazon. For the dry and transition seasons, however, the moisture flow must cross several major deforestation fronts mainly located in the central Amazon.

Thus, an important contribution of this work is to reveal that, contrary to the common perception that the tipping point is a single Amazon-wide event, certain parts of the Amazon are more vulnerable than others. Most notably, the southwestern Amazon (Peru and Bolivia) is most vulnerable to a possible tipping point, particularly stressed by disrupted dry season moisture flows over major deforestation fronts.

We will soon build off of these results in an upcoming policy-focused report that presents the major implications of the maintenance of aerial moisture flows for conservation. This analysis will include how to identify key conservation areas for each season based on the key concept of maintaining cascading moisture flow to the sensitive areas, in relation to protected areas, Indigenous territories, and major road networks. It will also reveal several policy implications that require urgent attention and new approaches to national governance and international cooperation. For example, It considers the implications of planned roads (most notably BR-319) and fortifying existing conservation areas and creating new ones in undesignated public lands.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Leo Model Foundation.

We thank the following colleagues for datasets and/or comments on earlier versions of the report:

Wei Weng

Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

Potsdam, Germany

Arie Staal

Assistant Professor

Environmental Sciences

Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development

Utrecht University

Juan Pablo Sierra

Institut des Géosciences de l’Environnement,

Université Grenoble Alpes, IRD, CNRS,

Grenoble, France

Jhan-Carlo Espinoza

Directeur de Recherche, Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement (IRD)

IGE Univ. Grenoble Alpes, IRD, CNRS (UMR 5001 / UR 252) – France

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Lima – Peru

Co-chair of ANDEX: A regional Hydroclimate Initiative for the Andes – GEWEX

Coordinator of the AMANECER Project (Amazon-Andes Connectivity)

Clara Zemp

University of Neuchâtel

Corine Vriesendorp

Director of Science

Conservación Amazónica – Peru (ACCA)

Federico E. Viscarra

Science Officer

Science Panel for the Amazon

Daniel Larrea

Director of the Science & Technology Program

Conservación Amazónica – Bolivia (ACEAA)

Citation

Finer M, Ariñez A, Sierra JP, Espinoza JC,, Weng W, Vriesendorp C, Bodin B, Beavers J (2025) The Amazon Tipping Point – Importance of Flying Rivers Connecting the Amazon. MAAP: 232.

Literature Cited

Agudelo, J., Espinoza, J.C., Junquas, C., Arias, P. A., Sierra, J. P., Olmo, M. E (2023) Future projections of low-level atmospheric circulation patterns over South Tropical South America: Impacts on precipitation and Amazon dry season length. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

Beveridge et al (2024) The Andes–Amazon–Atlantic pathway: A foundational hydroclimate system for social–ecological system sustainability. PNAS 121 (22) e2306229121

Boers N, Marwan N, Barbosa HM, and Kurths J. (2017) A deforestation-induced tipping point for the South American monsoon system. Scientific reports, 7(1), 41489.

Brando PM, Barlow J, Macedo MN, Silvério DV, Ferreira JN, et al (2025) Tipping Points of Amazonian Forests: Beyond Myths and Toward Solutions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. Vol. 50.

Commar, L.F.S., Abrahão, G.M., & Costa, M.H. (2023) A possible deforestation-induced synoptic-scale circulation that delays the rainy season onset in Amazonia. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 044041.

Delphine Clara Zemp, Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, Henrique M. J. Barbosa, Marina Hirota, Vincent Montade, Gilvan Sampaio, Arie Staal, Lan Wang-Erlandsson & Anja Rammig (2017) Nat Comms 8: 14681

Encalada A.C., Adalberto L. Val, Simone Athayde, Jhan Carlo Espinoza, Marcia Macedo, Mirian Marmontel, Guido Miranda, Maria Tereza Fernandez Piedade, Tiago da Mota e Silva & Julia Arieira (2021) Conserving the Amazon’s freshwater ecosystems’ health and connectivity. SPA Policy Brief.

Espinoza JC., Jimenez J.C., Marengo J.A. Schongart J., Ronchail J., Lavado-Casimiro W. Ribeiro JVM (2024) The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Sci Rep 14, 8107.

Fassoni-Andrade, A. C., Fleischmann, A. S., Papa, F., Paiva, R. C. D. d., Wongchuig, S., Melack, J. M., et al. (2021). Amazon hydrology from space: Scientific advances and future challenges. Reviews of Geophysics, 59, e2020RG000728.

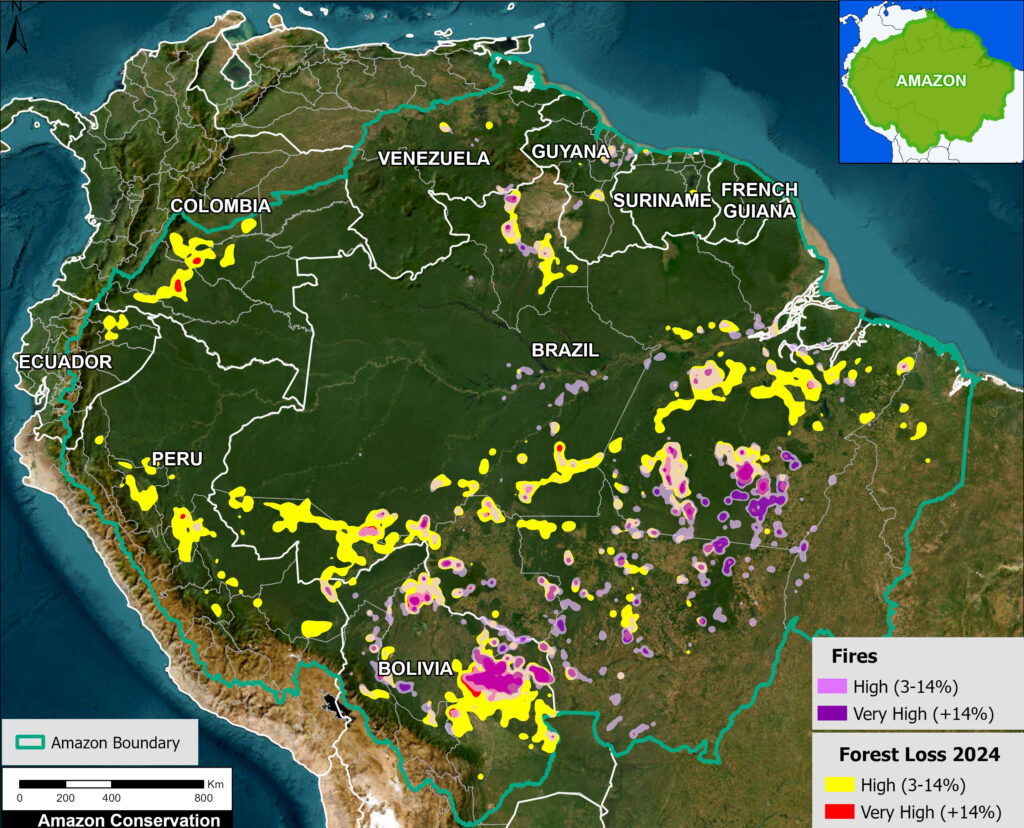

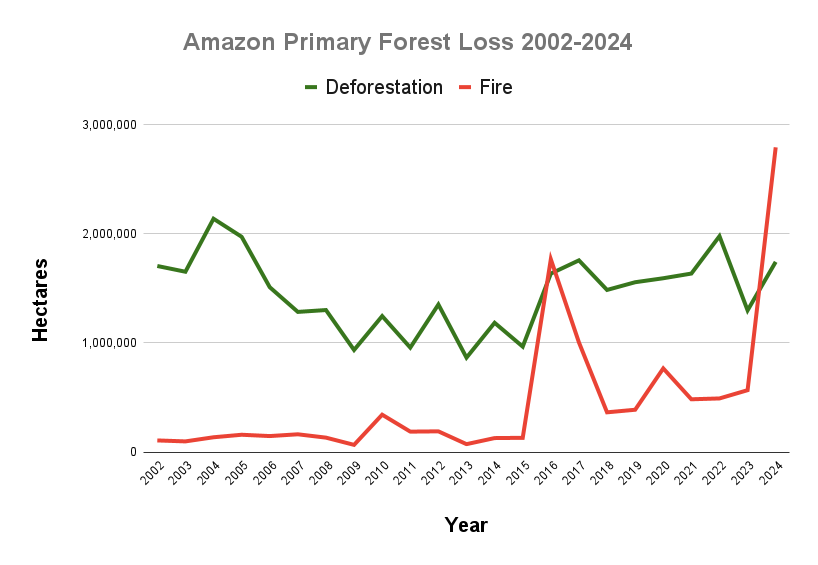

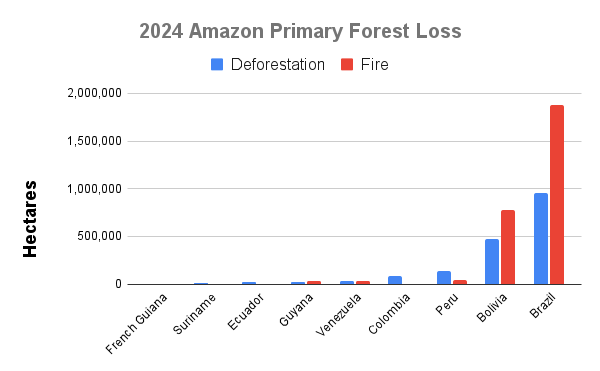

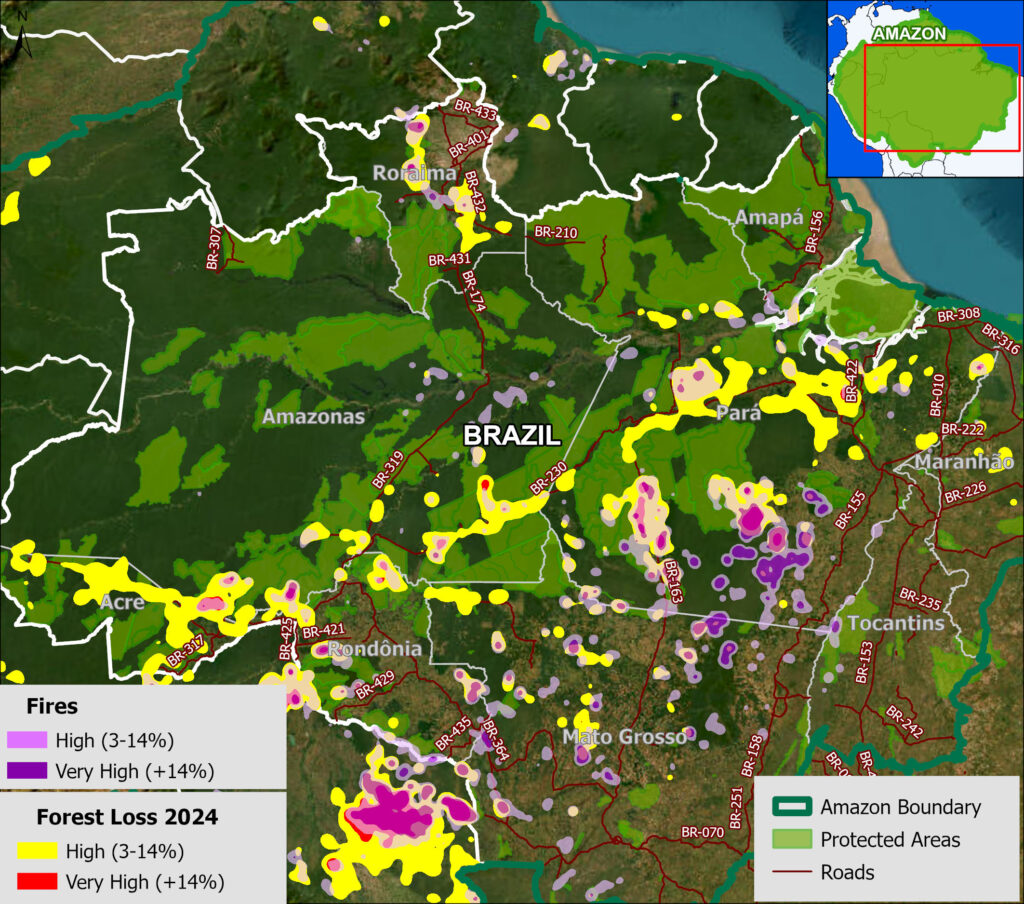

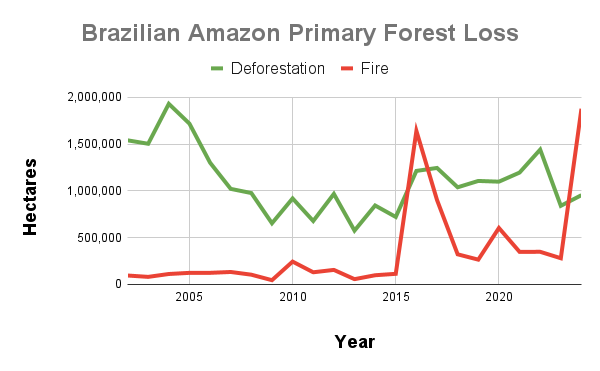

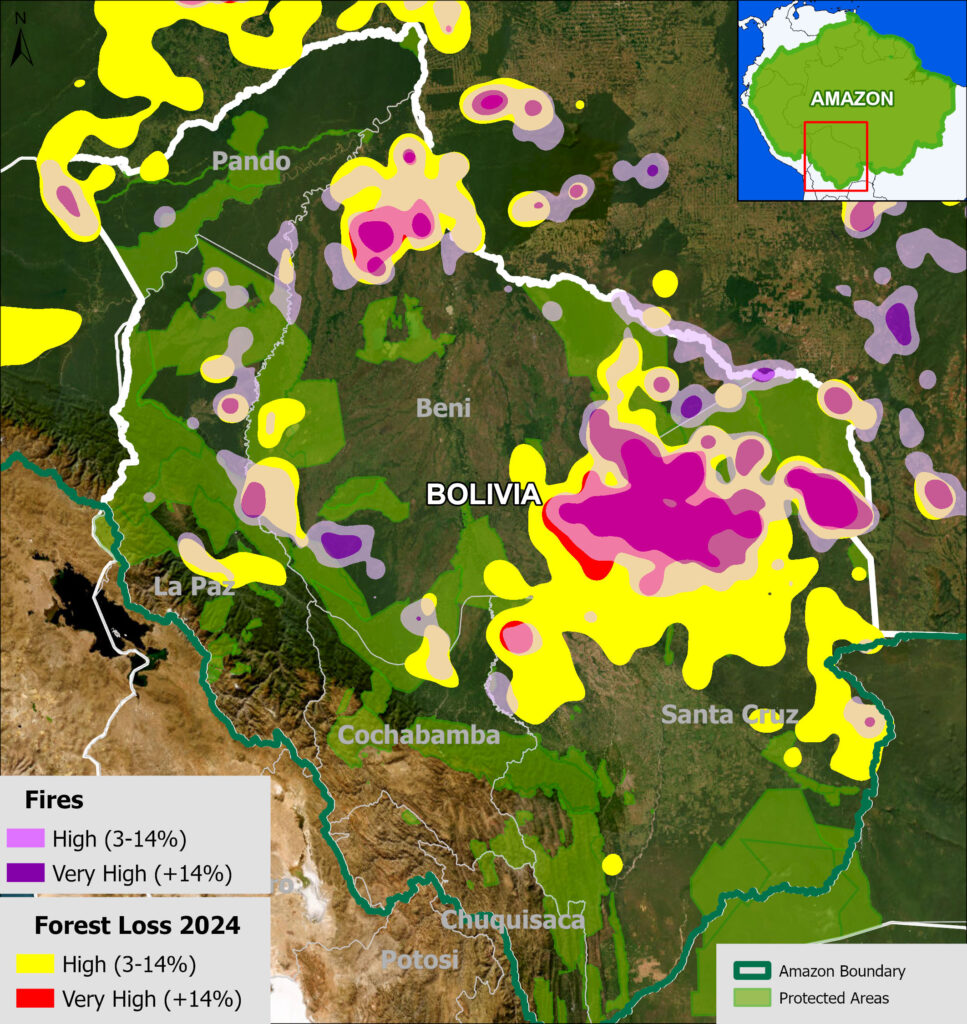

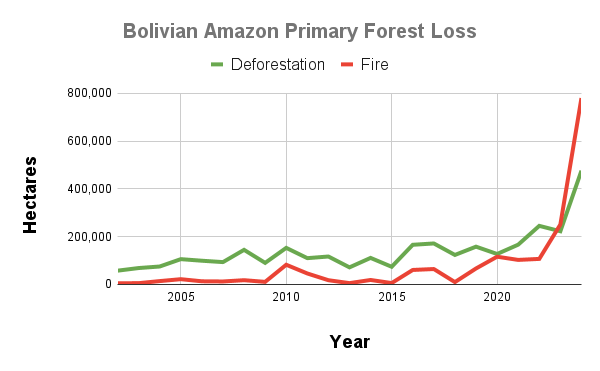

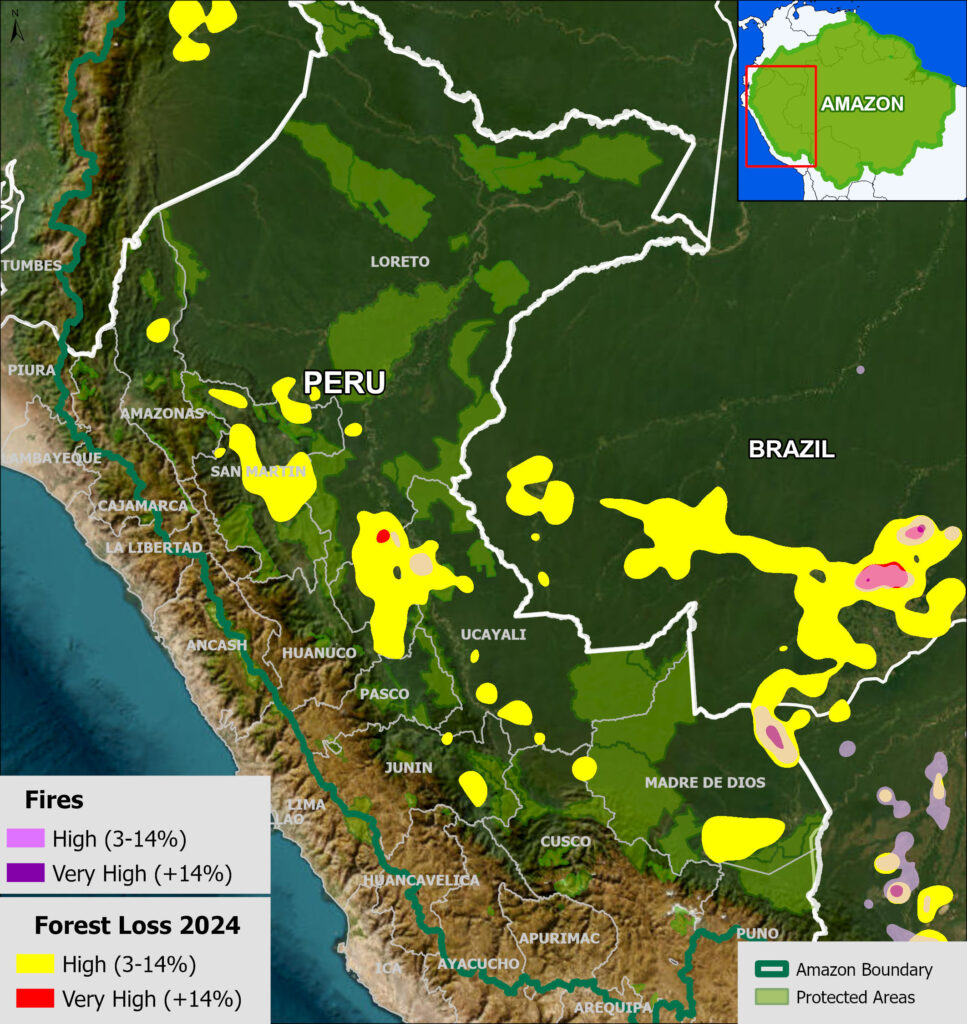

Finer M, Ariñez A, Mamani N, Cohen M, Santana A (2025) Amazon Deforestation & Fire Hotspots 2024. MAAP: 229.

Flores, B.M., Holmgren, M (2021) White-Sand Savannas Expand at the Core of the Amazon After Forest Wildfires. Ecosystems 24, 1624–1637.

Flores et al. (2024) Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system. Nature, 262 (555–564).

Franco et al. (2025) How climate change and deforestation interact in the transformation of the Amazon rainforest. Nature Communications 16:7944.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Biavati, G., Horányi, A., Muñoz Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Rozum, I., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Dee, D., Thépaut, J-N. (2023): ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS).

Hoyos, F. Dominguez, J. Cañón-Barriga, J. A. Martínez, R. Nieto, L. Gimeno & P. A. Dirmeyer (2018) Moisture origin and transport processes in Colombia, northern South America. Climate Dynamics. Volume 50, pages 971–990

Josefina Moraes Arraut, Carlos Nobre, Henrique M. J. Barbosa, Guillermo Obregon, and José Marengo (2012) Aerial Rivers and Lakes: Looking at Large-Scale Moisture Transport and Its Relation to Amazonia and to Subtropical Rainfall in South America. Journal of Climate 25 (2):543-556.

Keys, P. W., Van Der Ent, R. J., Gordon, L. J., Hoff, H., Nikoli, R., and Savenije, H. H. G. (2012) Analyzing precipitation sheds to understand the vulnerability of rainfall dependent regions, Biogeosciences, 9, 733–746.

Lovejoy T. & Nobre C. (2018) Amazon tipping point. Science Advances, 4(2)

Lovejoy T.E., C. Nobre (2019) Amazon tipping point: Last chance for action. Sci. Adv. 5, eaba 2949.

Marengo, J. , Cunha, A. , Espinoza, J.C. , Fu, R. , Schöngart, J. , Jimenez, J. , Costa, M. , Ribeiro, J. , Wongchuig, S. and Zhao, S (2024) The Drought of Amazonia in 2023-2024. American Journal of Climate Change, 13, 567-597.

Martinez J.A. and Dominguez F. (2014) Sources of Atmospheric Moisture for the La Plata River Basin. 27 (17) 6737–6753.

Miguez-Macho G, Fan Y (2012) The role of groundwater in the Amazon water cycle: 1. Influence on seasonal streamflow, flooding and wetlands. J Geophys Res Atmos.

Molina, R. D., Salazar, J. F., Martínez, J. A., Villegas, J. C., & Arias, P. A. (2019). Forest-induced exponential growth of precipitation

along climatological wind streamlines over the Amazon. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 124, 2589–2599.

Nehemy MF et al. (2025) Embolism resistance supports the contribution of dry-season precipitation to transpiration in eastern Amazon forests. PNAS 122: 33.

Qin, Y., Wang, D., Ziegler, A.D. et al. (2025) Impact of Amazonian deforestation on precipitation reverses between seasons. Nature 639, 102–108.

Ruiz-Vásquez M. Arias PA., Martinez JA., Espinoza JC. (2020) Effects of Amazon basin deforestation on regional atmospheric circulation and water vapor transport towards tropical South America. Climate Dynamics.

Sierra, J.P., Junquas, C., Espinoza, J.C., Segura, H., Condom, T., Andrade, M., Molina-Carpio, J., Ticona, L., Mardoñez, V., Blacutt, L., Polcher, J., Rabatel, A., Sicart, J. E. (2022) Deforestation Impacts on Amazon-Andes Hydroclimatic Connectivity. Climate Dynamics.

Sierra, J.P., Espinoza, JC., Junquas, C. Wongchuig S., Polcher J., Moron V., Fita L., Arias PA., Schrapffer A., Pennel R. (2023) Impacts of land-surface heterogeneities and Amazonian deforestation on the wet season onset in southern Amazon. Clim Dyn.

Staal, A., Tuinenburg, O.A., Bosmans, J.H.C. et al. (2018) Forest-rainfall cascades buffer against drought across the Amazon. Nature Clim Change 8, 539–543.

von Randow C, Manzi AO, Kruijt B et al (2004) Comparative measurements and seasonal variations in energy and carbon exchange over forest and pasture in South West Amazonia. Theor Appl Climatol 78:5–26.

WCS (2023) High Integrity Forest Investment Initiative (HIFOR): The Science Basis

Weng W. (2019), Aerial river management for future water in the context of land use change in Amazonia

Weng, Wei, Matthias K. B. Luedeke, Delphine C. Zemp, Tobia Lakes, and Juergen P. Kropp. (2018) “Aerial and Surface Rivers: Downwind Impacts on Water Availability from Land Use Changes in Amazonia.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 22 (1): 911–27

Wongchuig S, Espinoza JC, Condom T, Junquas C, Sierra JP, Fita L, Sörensson A, Polcher J. 2023. Changes in the surface and atmospheric water budget due to projected Amazon deforestation: Lessons from a fully coupled model simulation, Journal of Hydrology, Volume 625.

Zanin PR, Pareja-Quispe D, Espinoza JC. (2024) Evapotranspiration in the Amazon Basin: Couplings, hydrological memory and water feedback. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology.

Zemp, D. C., C-F Schleussner, H. M. J. Barbosa, and A. Rammig. (2017) “Deforestation Effects on Amazon Forest Resilience.” Geophysical Research Letters 44 (12): 6182–90

Zemp, D. C., Schleussner, C.-F., Barbosa, H. M. J., van der Ent, R. J., Donges, J. F., Heinke, J., Sampaio, G., and Rammig, A.(2017) On the importance of cascading moisture recycling in South America, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 13337–13359, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-13337-2014, 2014.

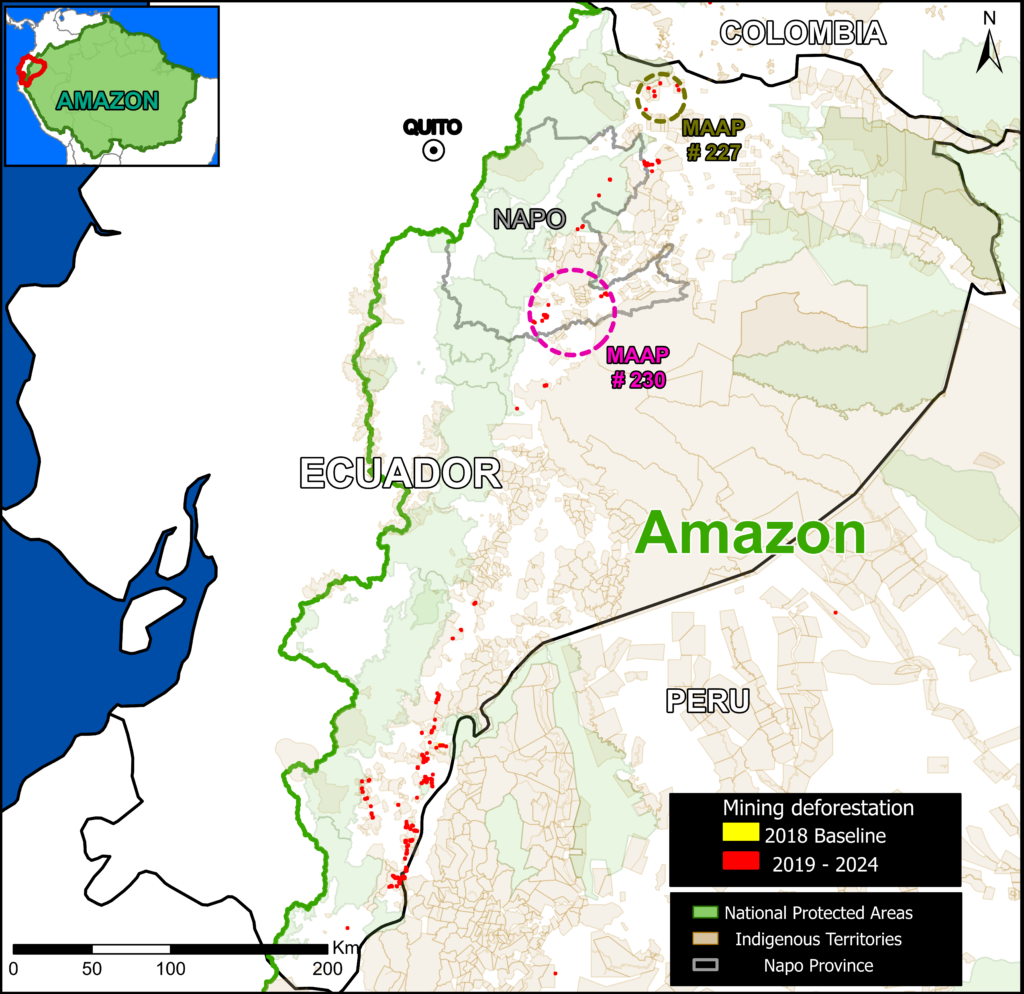

MAAP #230: Mining in the Ecuadorian Amazon, Central Sector – Napo Province

This is the second in a series of reports detailing the expansion of gold mining in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

In the first report (MAAP #227), we analyzed mining expansion in the northern sector, around the Cofán Bermejo Ecological Reserve, near the Colombian border.

In this current report, we focus on mining deforestation in the central sector, specifically in the Napo province, part of one of Ecuador’s main water systems.

Base Map 1 indicates these two areas in relation to the most recent mining detection data from Amazon Mining Watch (AMW), highlighting the most recent mining deforestation (2019-2024) in red.

Note that within and surrounding the current report focal area (purple circle), there are several Indigenous territories and two key protected areas (Sumaco Napo Galeras National Park and Colonso Chalupas Biological Reserve).

Mining in the Napo province

Napo, one of Ecuador’s six Amazonian provinces, is home to valuable Andean-Amazonian watersheds rich in ecosystem services, making it a priority area for biodiversity conservation and sustainable natural resource management. However, its main rivers are threatened by gold mining, the social and ecological consequences of which are profoundly negative.

In a previous report, MAAP #151, we warned about the rapid expansion of gold mining in the Yutzupino sector, on the banks of the Jatunyacu River. This sector has been the target of various control operations, such as the three so-called Manatí operations, and a technical report on the oversight and monitoring of illegal mining presented to Ecuador’s National Assembly in 2022.

In subsequent reports (MAAP #162 and MAAP #184), the area of analysis of mining deforestation in the Napo province was expanded to include the Jatunyacu, Anzu, and Huambuno Rivers.

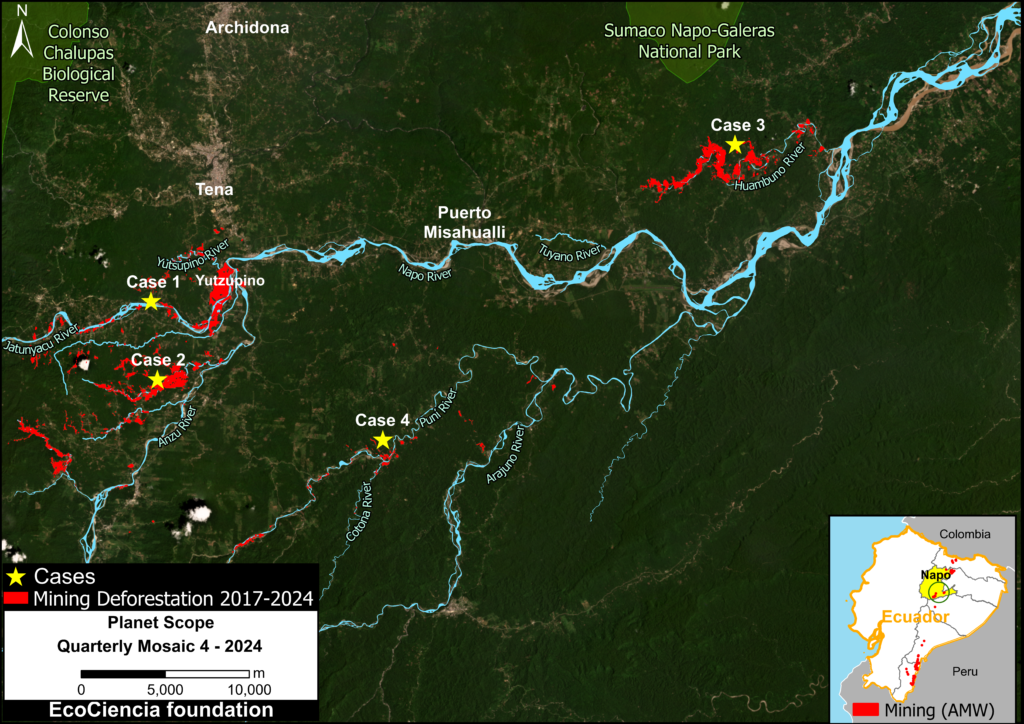

This current update presents more recent data (2024), incorporating four key case studies: the Jatunyacu, Anzu, Huambuno, and Puni-Cotona-Arajuno Rivers (see Base Map 2).

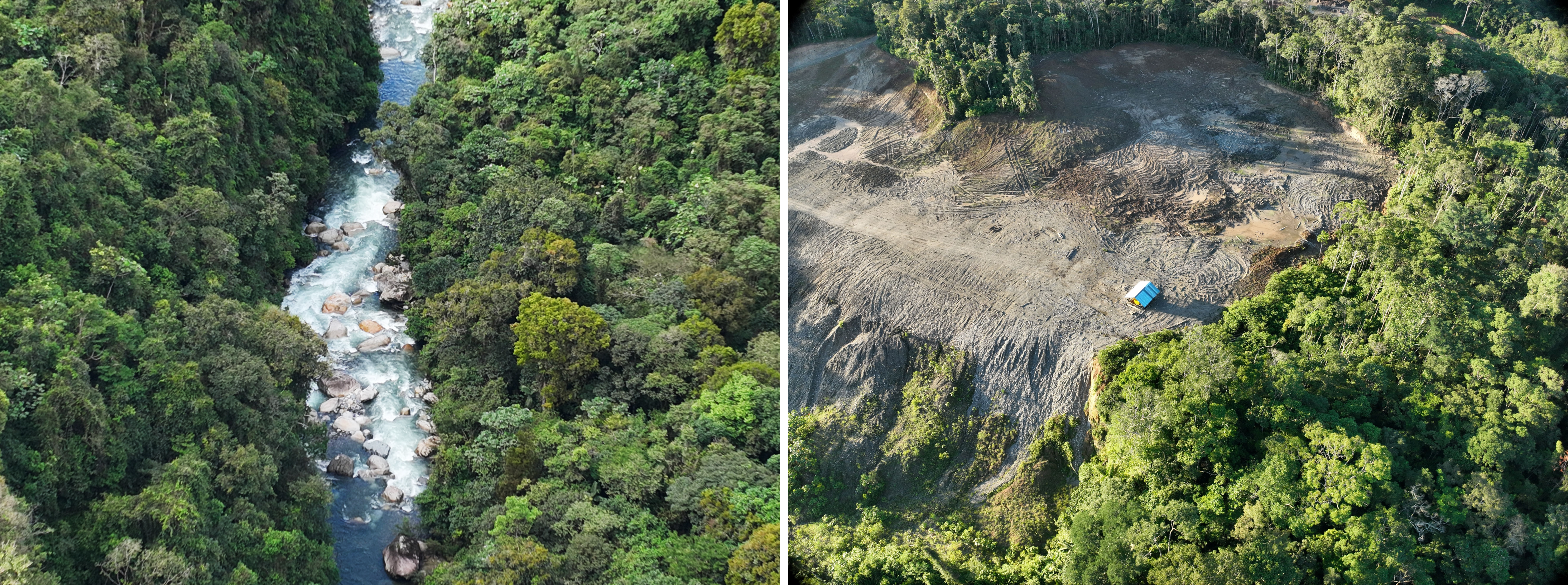

Gold mining not only poses environmental hazards, such as forest destruction, water pollution, and ecosystem degradation (see Image 1), but also causes social conflicts and disputes with local communities, who depend on the land and natural resources for their livelihoods and quality of life. The appreciation of gold in the international market poses a challenge to the implementation of sustainable economic alternatives such as ecotourism. However, the ecological and cultural importance of these aquatic ecosystems has generated sound conservation proposals, as detailed in MAAP #202.

Dynamics of gold mining deforestation

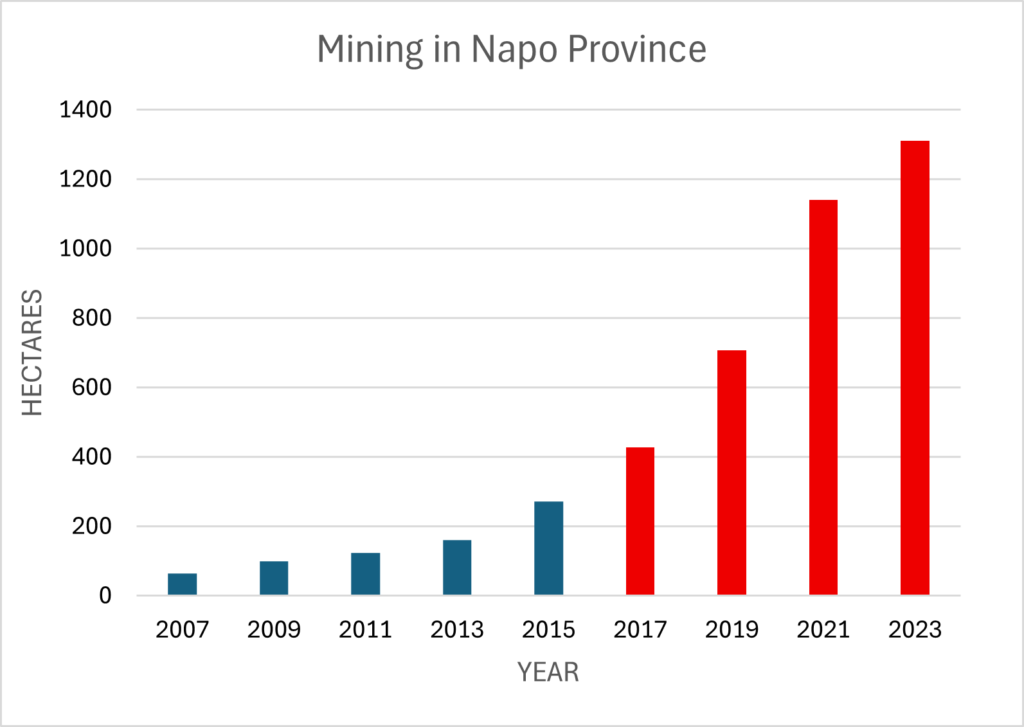

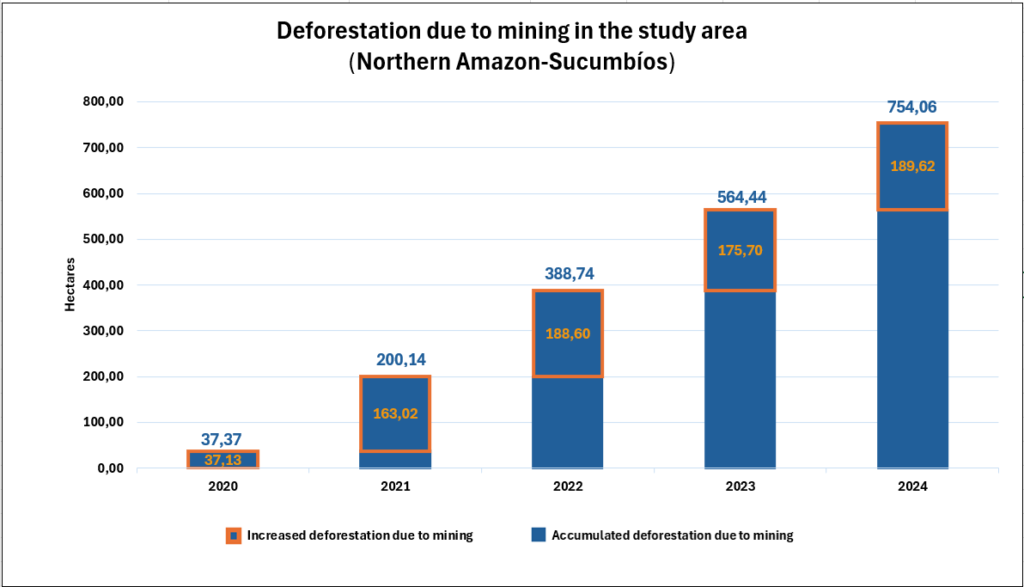

Chart 1, with biannual data, illustrated the growth of the mining area in Napo province from 2007 to 2023.

During this period, the total area linked to mining exceeded 1,300 hectares (3,200 acres).

The analysis reveals a trend of sustained increase in mining activity over time, with a particularly notable increase starting in 2017.

Case studies

We chose four key case studies to analyze the dynamics of the expansion of mining areas within the Napo province during the period 2017-2024 (see Base Map 2).

Cas3 1: Jatunyacu River

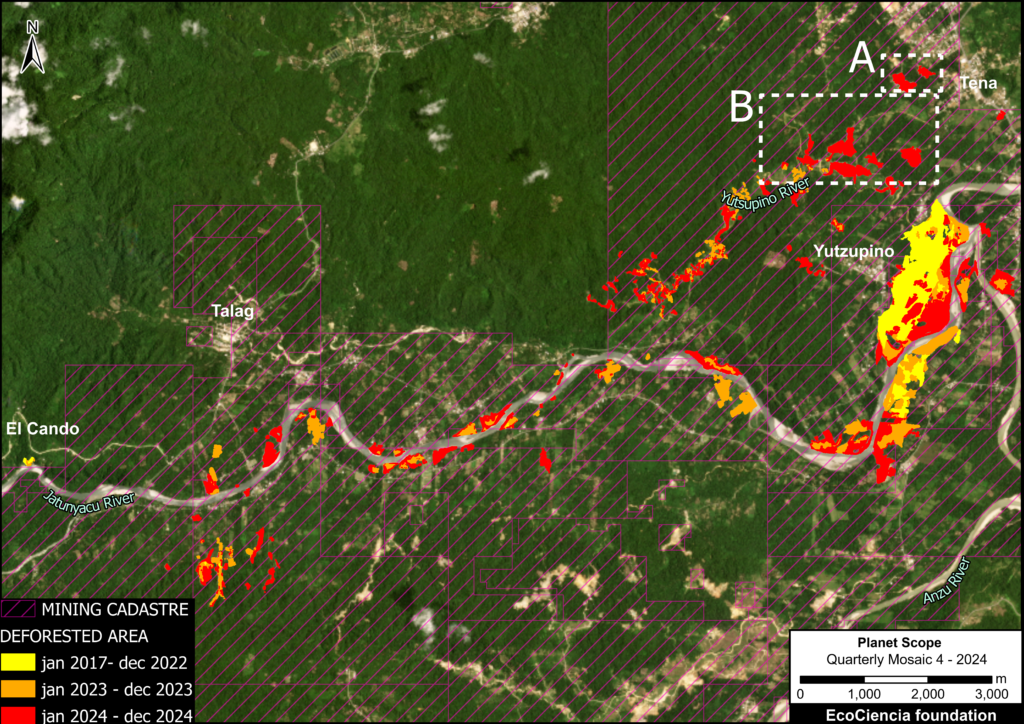

This case extends along the banks of the Jatunyacu River from the town of El Cando in the west to its confluence with the Anzu River in the Yutzupino sector. It also includes the Yutsupino River, a tributary of the Jatunyacu River, and several sectors located on the outskirts of the urban boundary south of the city of Tena. This has an important connotation, as it shows that mining activities are not only taking place in remote areas, but are also advancing into highly populated areas.

Between January 2017 and December 2022, 126 hectares were affected by mining. During 2023, the impacted area increased by 162 hectares, and in 2024 a further increase of 214 hectares was recorded. In total, from January 2017 to December 2024, the area affected by mining totals 502 hectares, approximately equivalent to 703 professional soccer fields.

Furthermore, we found that some mining activity has been carried out outside the areas authorized by the mining registry, that is, in areas that do not have the corresponding permits for such activity. These areas total 6.62 hectares, representing just 0.01% of the total identified, but are significant due to their unauthorized nature.

Most mining activities are located within concessions registered in the mining registry. However, few concessions have the additional permits required to carry out mining activities. Furthermore, some of these authorized concessions, although they have processed and received additional permits, have been suspended due to non-compliance with the environmental management plan and violations of the current environmental license.

In order to analyze the details of mining activities in this case study, two areas, indicated as A and B (see Case 1) were selected for further analysis.

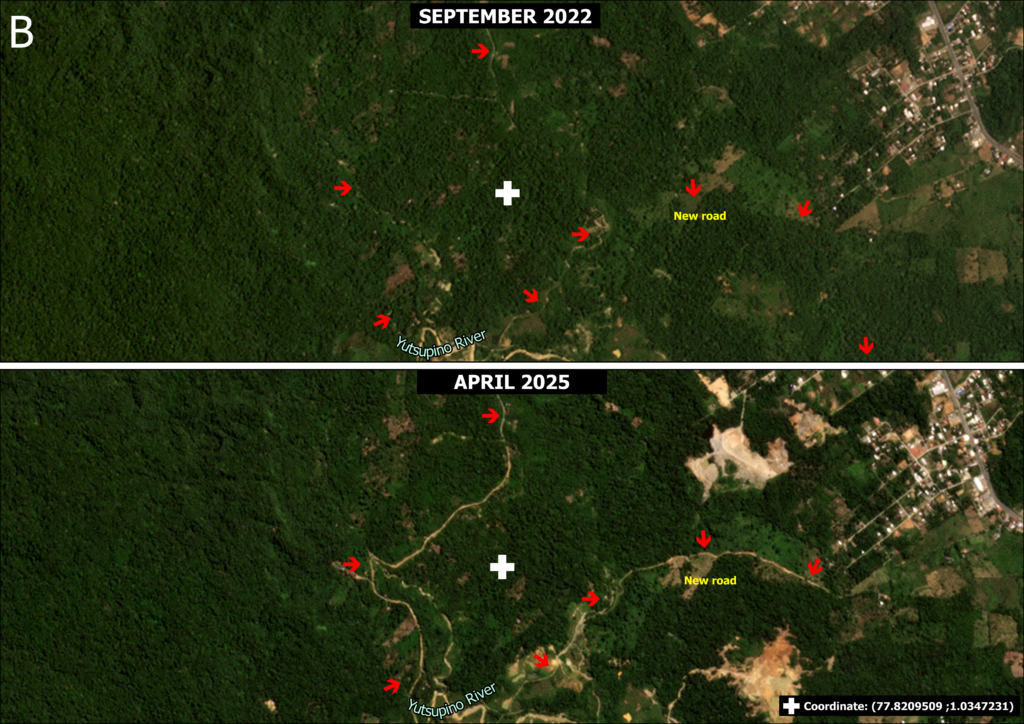

In the case of area A, Panel 1 shows the expansion of mining activity between September 2022 (top left panel) and April 2025 (top right panel).

Furthermore, drone photographs from June 2025 reveal additional details, such as mining pits, the removal of vegetation cover, eroded soil, and other effects produced by mining activity.

For area B, panel 2 shows the opening of 4.43 km of new roads entering the Yutsupino River between 2022 and 2025, which has facilitated access for the opening of new mining fronts, avoiding a police checkpoint at the entrance to the Yutzupino sector in Puerto Napo.

Case 2: Anzu

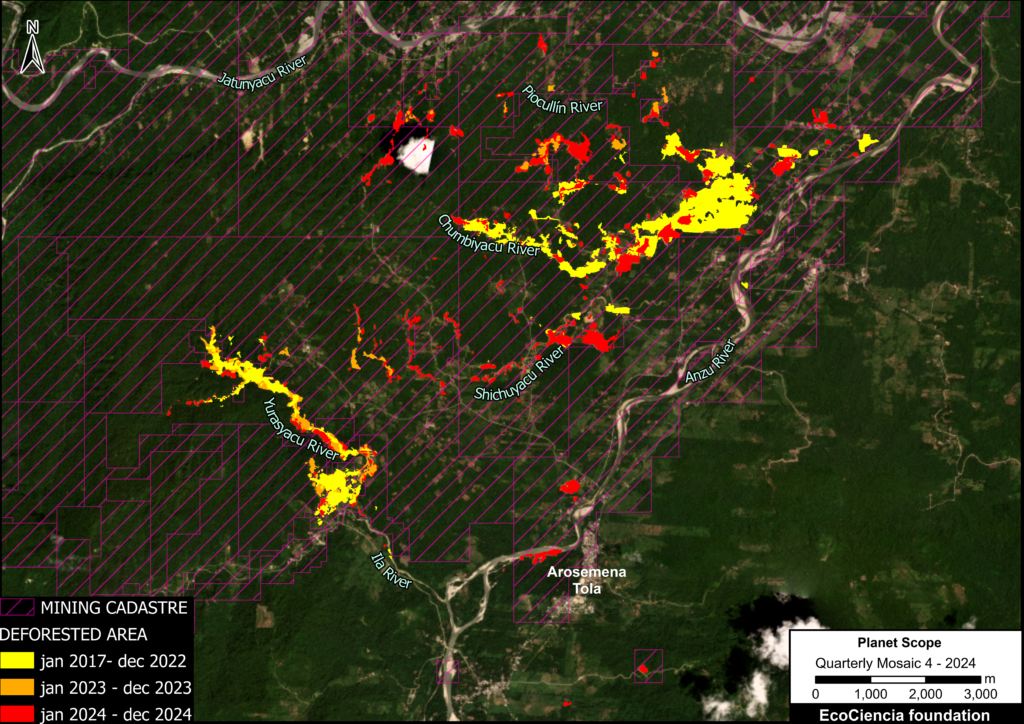

Case 2 extends over the Piocullín, Chumbiyacu, Shichuyacu, Ila, Yurasyacu, and Anzu rivers, where 329 hectares were impacted by mining during the period from January 2017 to December 2022.

An additional 63 hectares were impacted in 2023, and 243 hectates in 2024.

In total, 635 hectares in this area were impacted by mining, equivalent to 889 professional soccer fields.

Additionally, mining activity was identified outside the cadastre, corresponding to 94 hectares, representing 15% of the total identified.

Case 3: Huambuno

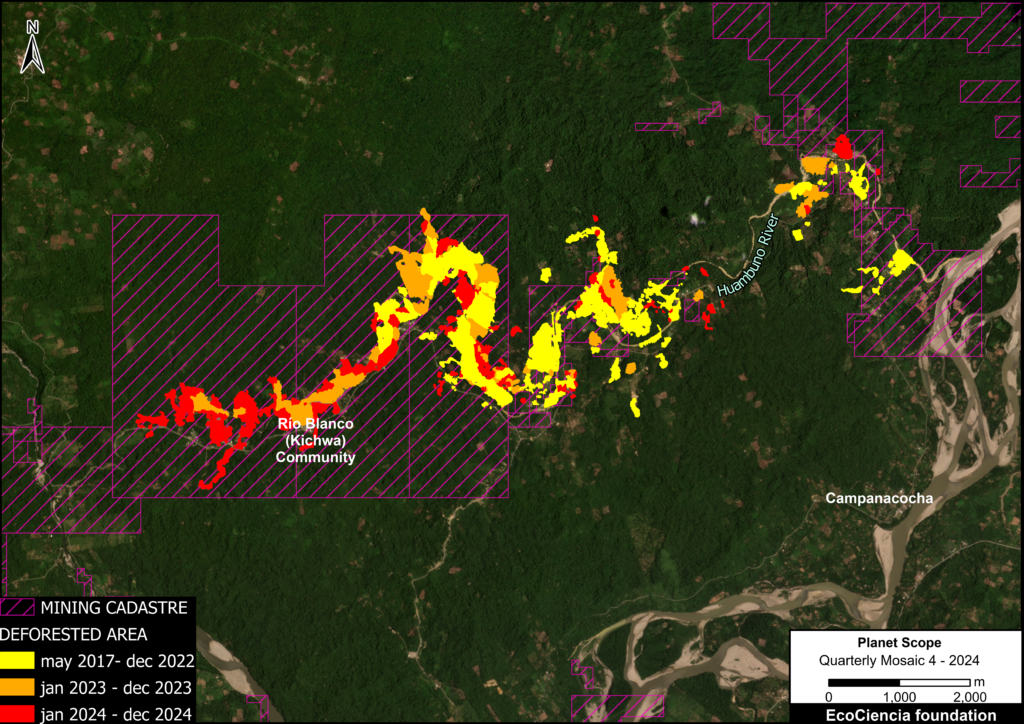

In this case, we conducted an analysis until December 2024 on the situation on the banks of the Huambuno River.

MAAP #184 documented a mining expansion of 238 hectares affected by mining in this area from May 2017 to January 2023.

In this new analysis, an increase of 124 hectares was identified for the year 2023 and an increase of 130 hectares for the year 2024.

This adds up to a total of 492 hectares (equivalent to 689 soccer fields) affected by mining from May 2017 to December 2024.

Additionally, 115 hectares of mining activity were identified outside the cadastre, representing 23% of the total identified.

Case 4: Puní-Cotona-Arajuno

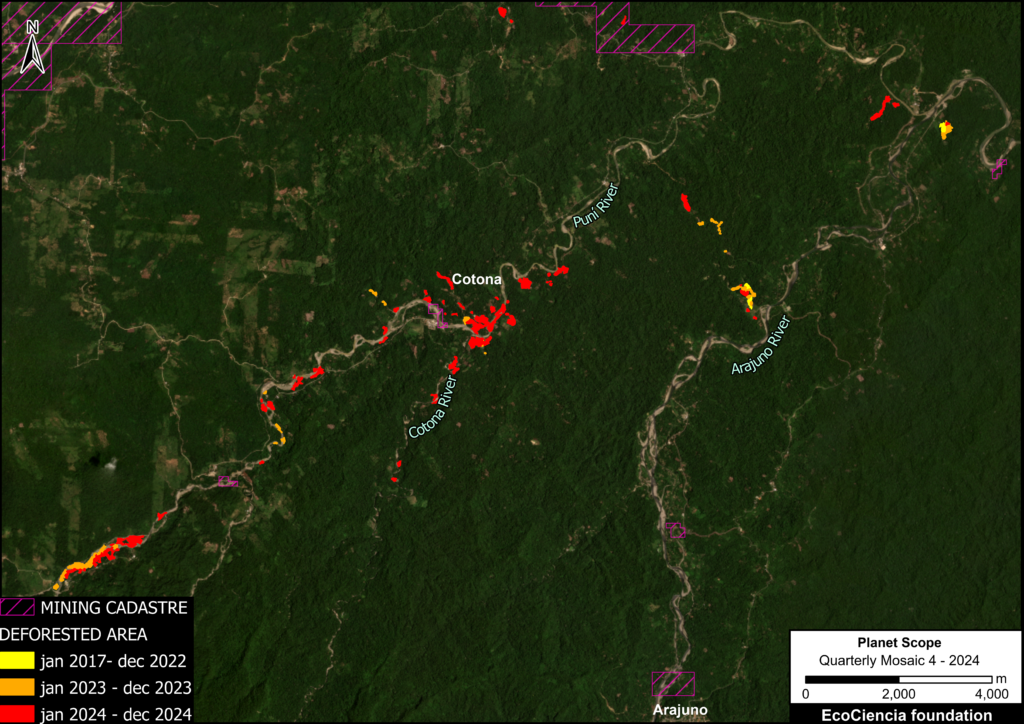

This case study analyzes a sector with little overlap in the mining registry, where unauthorized mining activities grew by approximately 2,700% from the first monitoring period, between 2017 and 2022, to 2024.

Between January 2017 and December 2022, only 4 hectares affected by mining activities were identified in the area.

In 2023, the area affected increased by 26 hectares, and in 2024, an additional increase of 82 hectares was recorded.

In total, during the period analyzed, 112 hectares were impacted by mining activity in the area surrounding the Puní, Cotona, and Arajuno rivers, equivalent to approximately 157 professional soccer fields.

Additionally, 111 hectares of mining activity were identified outside the official land registry, corresponding to 99% of the total identified, reflecting a strong presence of unauthorized mining in this sector.

Recommendations for public policy:

The recent deforestation caused by mining activities described above highlights key policy needs. Below, we present seven recommendations based on Ecuador’s existing legal framework and related policies for implementation.

1. Strengthen the investigation and control processes of the competent authorities in areas with mining potential that are not registered in the current mining cadastre.

Article 56 of Law 45 provides clear authority for enforcement actions against illegal mineral exploitation, defining such activities as those carried out “without a valid title or the corresponding legal permit.” In this regard, we recommend that the Mining Regulation and Control Agency (ARCOM) establish a comprehensive surveillance system that integrates satellite image analysis with ground verification protocols to identify unauthorized mining activities in real time.