The Ecuadorian Chocó, located on the other (western) side of the Andes Mountains from its Amazonian neighbor, is renowned for its high levels of endemic species (those that live nowhere else on Earth).

It is part of the “Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena” Biodiversity Hotspot, home to numerous endemic plants, mammals, and birds (1,2), such as the Long-wattled Umbrellabird.

It is also one of the most threatened tropical forests in the world (1).

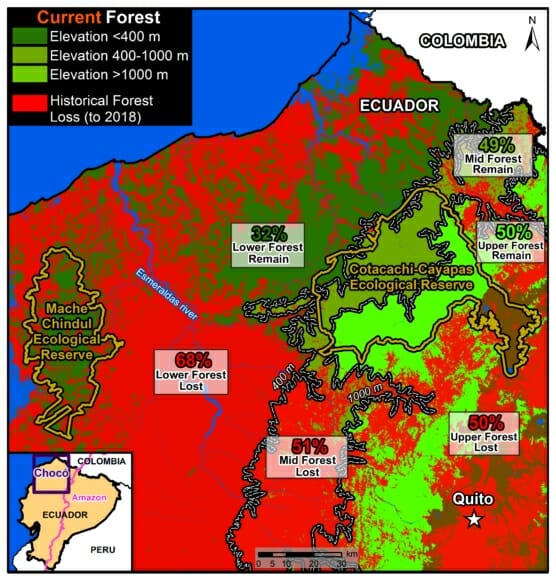

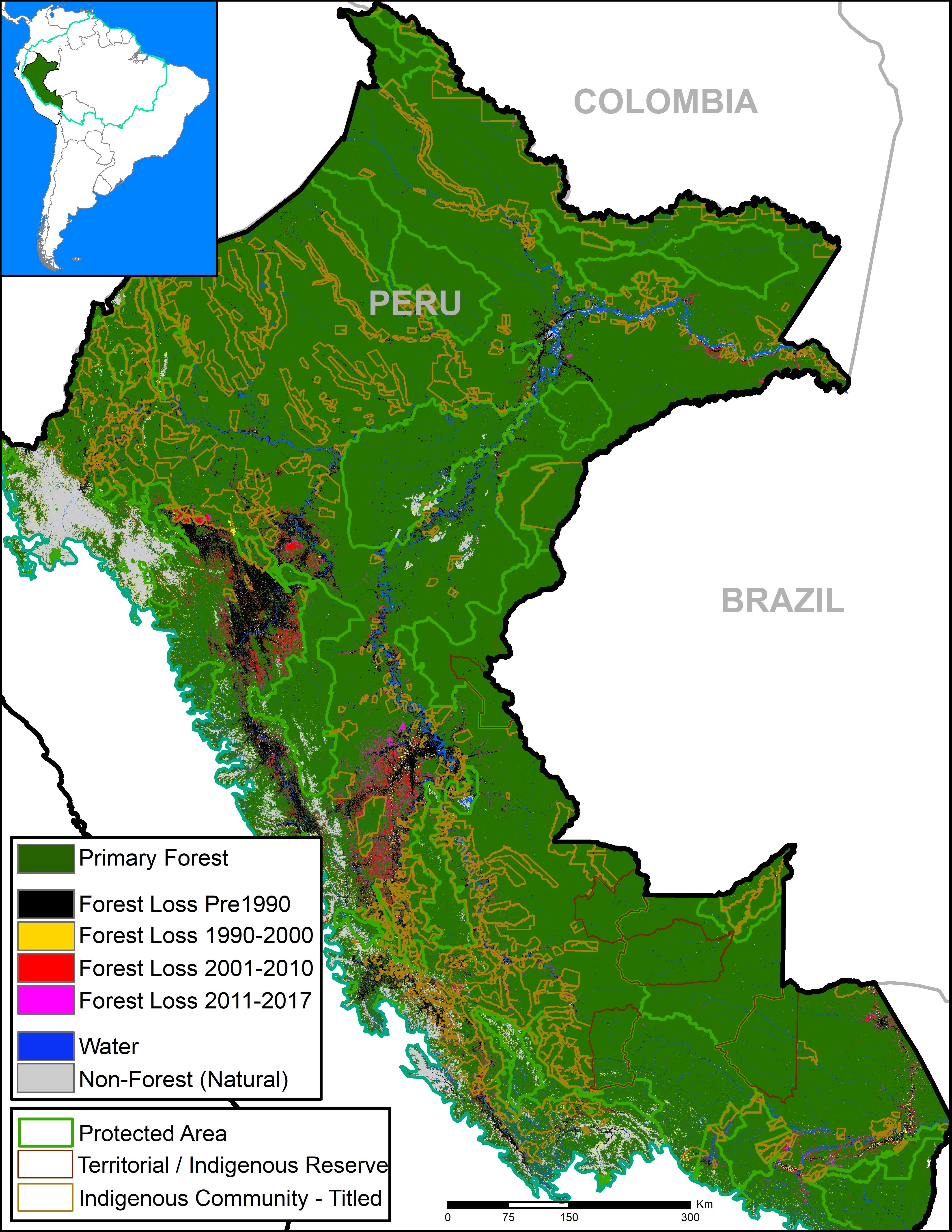

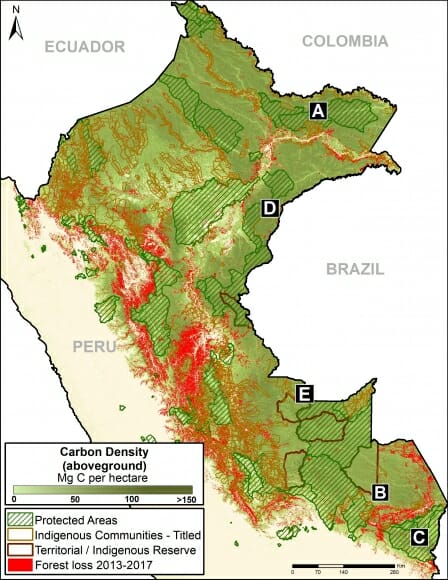

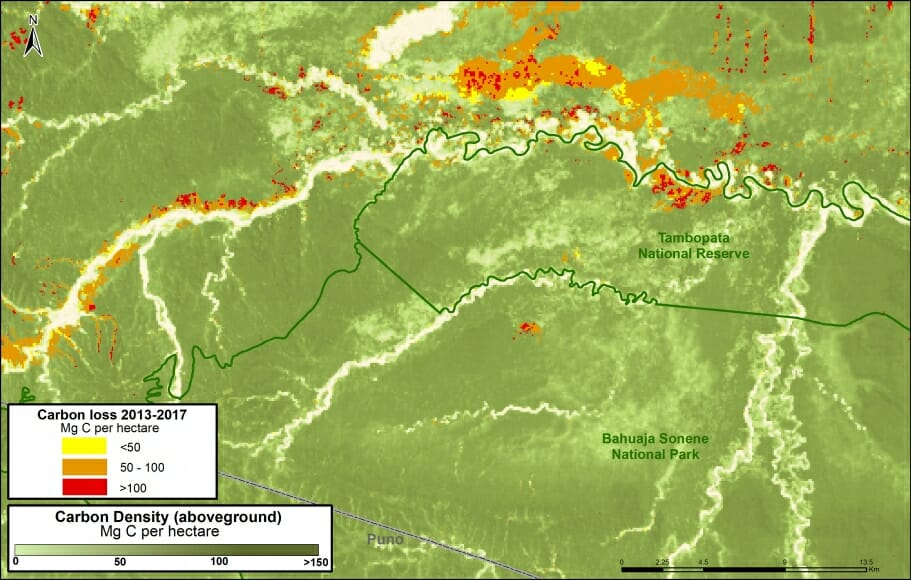

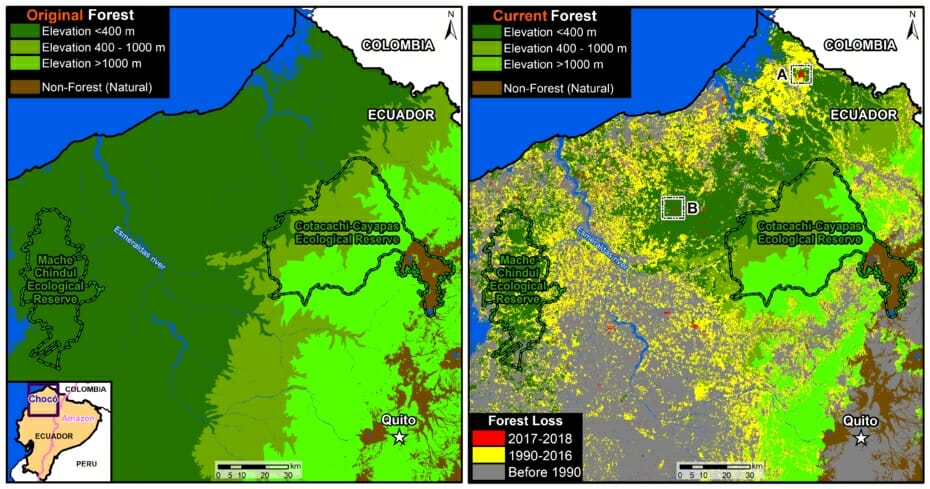

Here, we conduct a deforestation analysis for the northern Ecuadorian Chocó (see Base Map below) to better understand the current conservation scenario. Importantly, we compare the original forest extent (left panel) to the actual forest cover (right panel).

We document the loss of over 60% (1.8 million hectares) of low, mid, and upper elevation forest (compare the three tones of green between panels).

See our other Key Results below.

Base Map

Key Results

Our key results include:*

- 61% forest loss (1.8 million hectares) across all three elevations.

- 68% loss (1.2 million ha) of lowland rainforest,

- 50% loss (611,200 ha) of mid and upper elevation forests.

.

- 20% of the forest loss (365,000 ha) occurred after 2000.

- 4,650 ha lost during most recent 2017-18 period (mostly in lowlands).

- 39% total forest remaining (1.17 million ha) across all three elevations.

- Just 32% (569,000 ha) lowland rainforest remaining.

- 99% of Cotacachi-Cayapas Ecological Reserve remaining.

- 61% of Mache-Chindul Ecological Reserve remaining.

*Forest loss data corresponds to the study area indicated in the Base Map. Data sources: pre-2017 from Ecuadorian Environment Ministry; 2017-18 from University of Maryland (Hansen 2013). Elevation definitions: Lowland forest <400 meters (dark green), mid-elevation forest 400-1000 m (olive green), and upper elevation forest >1000 m (bright green).

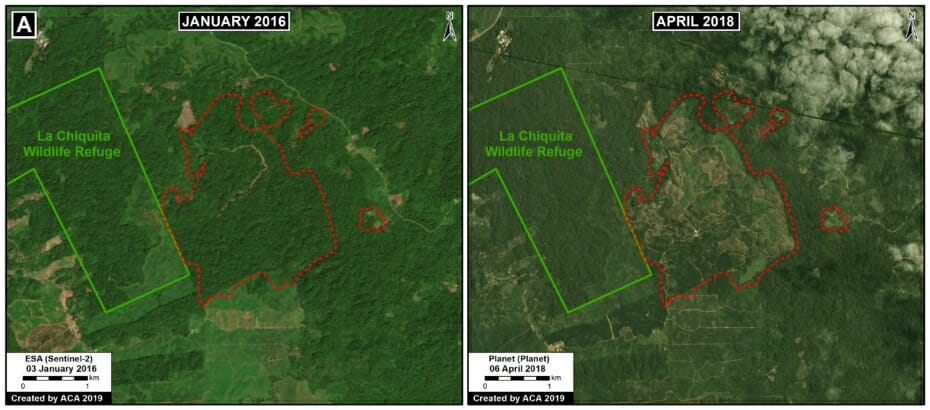

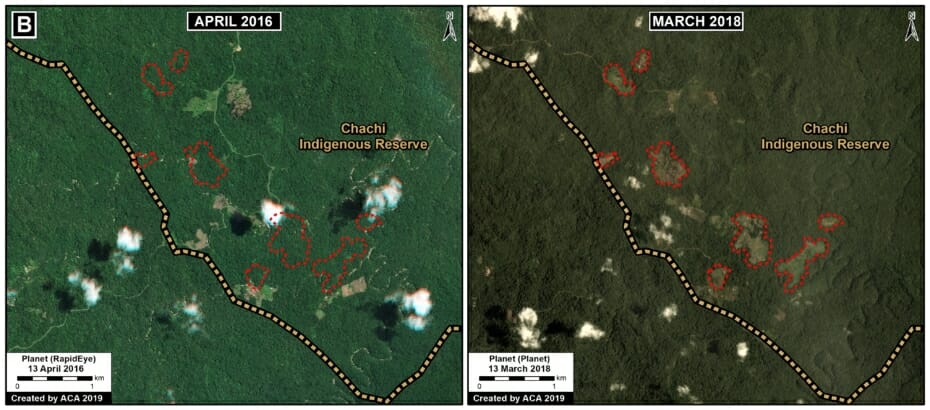

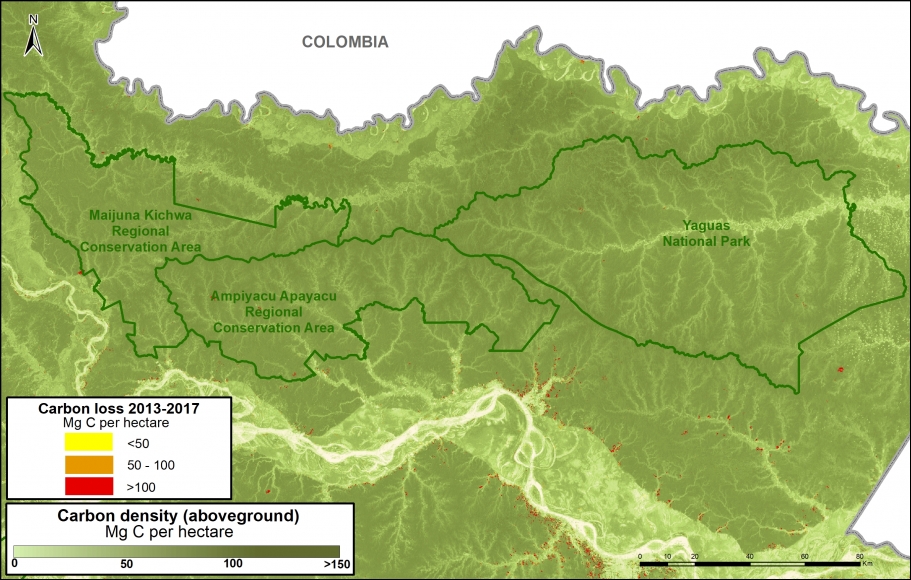

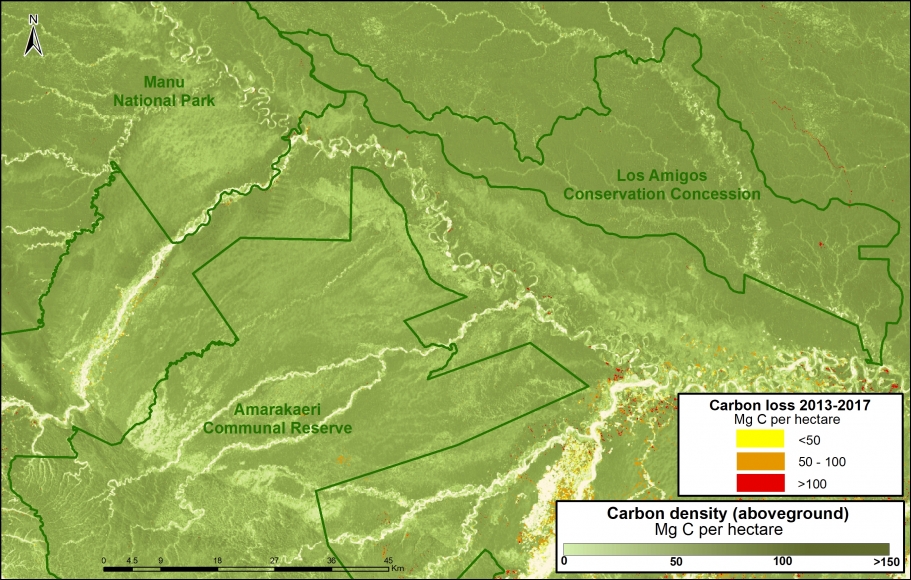

High Resolution Zooms

In the Base Map, we indicate two areas (insets A and B) where we zoom in with high-resolution satellite imagery to see what recent deforestation looks like in the region.

Zoom A shows the deforestation of 380 hectares directly to the north of an oil palm plantation, possibly for an expansion.

Zoom B shows the deforestation of 50 hectares with the Chachi Indigenous Reserve.

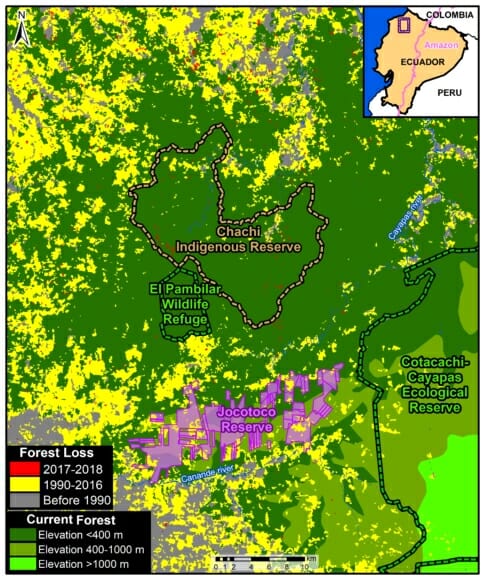

Conservation Opportunity

Efforts are underway to protect a critical stretch of low to mid elevation Chocó forest to the west of Cotacachi-Cayapas Ecological Reserve.

It involves the unique opportunity to acquire over 22,000 hectares of forest that would help safeguard connectivity between public and private conservation and indigenous areas. Connecting these areas provides the only opportunity to protect the entire altitudinal gradient from 100-4900 m on the western slope of the tropical Andes. It will also establish an effective buffer zone for governmental reserves and reduce the socio-economic vulnerability of local communities.

To support this effort, please contact the Jocotoco Foundation (Martin.Schaefer@jocotoco.org) or the International Conservation Fund of Canada (carlos@ICFCanada.org).

References

1) Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (2005) Ecosystem Profile: Tumbes-Chocó-Magdalena. Link: https://www.cepf.net/our-work/biodiversity-hotspots/tumbes-choco-magdalena

2) Mittermeier RA et al (2011) Global Biodiversity Conservation: The Critical Role of Hotspots. Biodiversity Hotspots, 3-22.

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Schaefer (Jocotoco), C. Garcia (ICFC), D. Pogliani (ACCA), S. Novoa (ACCA), R. Catpo (ACCA), H. Balbuena (ACCA) y T. Souto (ACA) for helpful comments on earlier versions of this report.

Citation

Finer M, Mamani N (2019) Saving the Ecuadorian Chocó. MAAP: 102.