See MAAP #118 for background information about real-time fire monitoring work.

See MAAP #118 for background information about real-time fire monitoring work.

As presented in MAAP #118, Amazon Conservation launched a real-time fire monitoring app that specializes in the rapid and user-friendly detection and visualization of major Amazon fires.

In a novel approach, the app combines data from the atmosphere (aerosol emissions in smoke) and the ground (heat anomalies) to effectively monitor large Amazon fires.

As detailed below, the app just detected the 12th major Amazon fire of the year on June 29, 2020 (see the high-resolution image to the right).

It burned 587 hectares (1,451 acres) of land deforested in 2019.

Thus far, all 12 major Amazon fires of 2020 have:

Below, we describe the process of using the app to detect and confirm the fire on June 29.

Step 1. Detection of elevated emissions in the southeastern Brazilian Amazon (Mato Grosso).

Step 3. Adjust the transparency to see the underlying fire alerts that indicate the exact location of the fires. Obtain coordinates of the source of the fires.

Step 4. Confirm fire with satellite imagery. For example, here is a high resolution image from Planet Explorer showing the fire burning on June 29.

Step 5. Using Planet’s extensive imagery archive, we were able to determine that the fires were burning an area deforested in 2019 (and not a forest fire). In the timelapse below, see that the deforestation occurred between September and October 2019, and then burned on June 29, 2020. The final image shows the day after the fires, June 30, to see the full extent of the burn.

-10.99, -55.13

This work was supported by the following major funders: USAID/NASA (SERVIR), Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, and Erol Foundation.

Finer M, Villa L (2020) Amazon Fire Tracker 2020: Brazil #12 (June 29). MAAP.

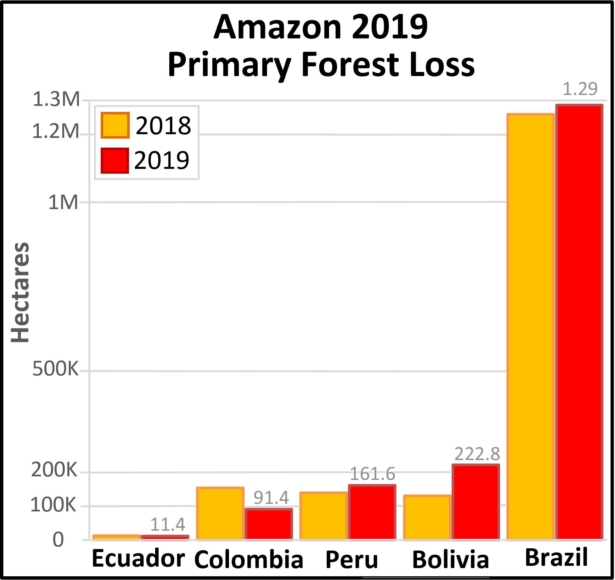

Newly released data for 2019 reveals the loss of over 1.7 million hectares (4.3 million acres) of primary Amazon forest in our 5 country study area (Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru).* That is twice the size of Yellowstone National Park.

Table 1 shows 2019 deforestation (red) in relation to 2018 (orange).

Primary forest loss in the Brazilian Amazon (1.29 million hectares) was over 3.5 times higher than the other four countries combined, with a slight increase in 2019 relative to 2018. Many of these areas were cleared in the first half of the year and then burned in August, generating international attention.

Primary forest loss rose sharply in the Bolivian Amazon (222,834 hectares), largely due to uncontrolled fires escaping into the dry forests of the southern Amazon.

Primary forest loss rose slightly in the Peruvian Amazon (161,625 hectares) despite a relatively successful crackdown on illegal gold mining, pointing to small-scale agriculture (and cattle) as the main driver.

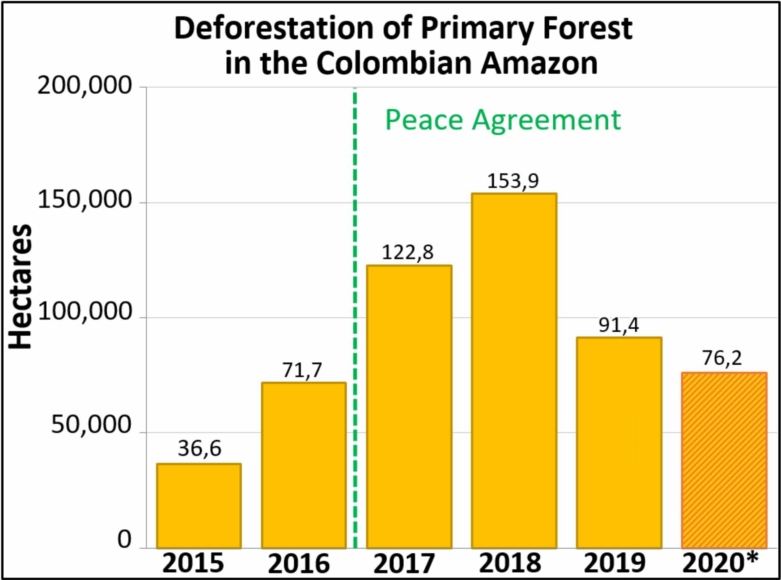

On the positive side, primary forest loss decreased in the Colombian Amazon (91,400 hectares) following a major spike following the 2016 peace accords (between the government and FARC). It is worth noting, however, that we have now documented the loss of 444,000 hectares (over a million acres) of primary forest in the Colombian Amazon in the past four years since the peace agreement (see Annex).

*Two important points about the data. First, we use annual forest loss from the University of Maryland to have a consistent source across all five countries. Second, we applied a filter to only include loss of primary forest (see Methodology).

The Base Map below shows the major 2019 deforestation hotspots across the Amazon.

Many of the major deforestation hotspots were in Brazil. Early in the year, in March, there were uncontrolled fires up north in the state of Roraima. Further south, along the Trans-Amazonian Highway, much of the deforestation occurred in the first half of the year, followed by the high profile fires starting in late July. Note that many of these fires were burning recently deforested areas, and were not uncontrolled forest fires (MAAP #113).

The Brazilian Amazon also experienced escalating gold mining deforestation in indigenous territories (MAAP #116).

Bolivia also had an intense 2019 fire season. Unlike Brazil, many were uncontrolled fires, particularly in the Beni grasslands and Chiquitano dry forests of the southern Bolivian Amazon (MAAP #108).

In Peru, although illegal gold mining deforestation decreased (MAAP #121), small-scale agriculture (including cattle) continues to be a major driver in the central Amazon (MAAP #112) and an emerging driver in the south.

In Colombia, there is an “arc of deforestation” in the northwestern Amazon. This arc includes four protected areas (Tinigua, Chiribiquete and Macarena National Parks, and Nukak National Reserve) and two Indigenous Reserves (Resguardos Indígenas Nukak-Maku and Llanos del Yari-Yaguara II) experiencing substantial deforestation (MAAP #120). One of the main deforestation drivers in the region is conversion to pasture for land grabbing or cattle ranching.

The baseline forest loss data presented in this report were generated by the Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) laboratory at the University of Maryland (Hansen et al 2013) and presented by Global Forest Watch. Our study area is strictly what is highlighted in the Base Map.

For our estimate of primary forest loss, we used the annual “forest cover loss” data with density >30% of the “tree cover” from the year 2001. Then we intersected the forest cover loss data with the additional dataset “primary humid tropical forests” as of 2001 (Turubanova et al 2018). For more details on this part of the methodology, see the Technical Blog from Global Forest Watch (Goldman and Weisse 2019).

For boundaries, we used the biogeographical limit (as defined by RAISG) for all countries except Bolivia, where we used the Amazon watershed limit (see Base Map).

All data were processed under the geographical coordinate system WGS 1984. To calculate the areas in metric units, the projection was: Peru and Ecuador UTM 18 South, Bolivia UTM 20 South, Colombia MAGNA-Bogotá, and Brazil Eckert IV.

Lastly, to identify the deforestation hotspots, we conducted a kernel density estimate. This type of analysis calculates the magnitude per unit area of a particular phenomenon, in this case forest cover loss. We conducted this analysis using the Kernel Density tool from Spatial Analyst Tool Box of ArcGIS. We used the following parameters:

Search Radius: 15000 layer units (meters)

Kernel Density Function: Quartic kernel function

Cell Size in the map: 200 x 200 meters (4 hectares)

Everything else was left to the default setting.

For the Base Map, we used the following concentration percentages: Medium: 7%-10%; High: 11%-20%; Very High: >20%.

Goldman L, Weisse M (2019) Explicación de la Actualización de Datos de 2018 de Global Forest Watch. https://blog.globalforestwatch.org/data-and-research/blog-tecnico-explicacion-de-la-actualizacion-de-datos-de-2018-de-global-forest-watch

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342 (15 November): 850–53. Data available on-line from: http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest.

Turubanova S., Potapov P., Tyukavina, A., and Hansen M. (2018) Ongoing primary forest loss in Brazil, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia. Environmental Research Letters https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aacd1c

We thank G. Palacios for helpful comments to earlier versions of this report.

This work was supported by the following major funders: Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, Erol Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, and Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI).

Finer M, Mamani N (2020) 2019 Amazon Deforestation. MAAP: 122.

As presented in MAAP #118, Amazon Conservation launched a real-time fire monitoring app that specializes in detection of elevated aerosol emissions in the smoke coming from burning Amazon fires. As detailed below, the app just detected the fourth major Amazon fire of 2020 on June 17. All four fires thus far have been in the state of Mato Grosso and burning recently deforested areas (see MAAP #113 for background).

Step 1. Detection of elevated emissions in the southeastern Brazilian Amazon (Mato Grosso).

Step 3. Adjust the transparency to see the underlying fire alerts that indicate the exact location of the fires. Obtain coordinates of the source of the fires.

Step 4. Check the satellite imagery in Planet Explorer. Here is a high resolution Planet image showing the fire burning on June 17. Also see the slider below, comparing the the June 17 fires with a pre-fire image from June 10.

[twenty20 img1=”9167″ img2=”9168″ width=”75%” offset=”0.5″]

Imagery source: Planet.

Step 5. Using Planet’s extensive imagery archive, we were able to determine that the fires were burning an area deforested in 2019 (and not a forest fire).

Coordinates: -10.45, -53.55

This slider shows us how aerosol emission data allows users to prioritize hundreds (or thousands) of heat-based fire alerts. In other words, the aerosol data indicates just the fires that are actually burning lots of biomass and putting out abundant smoke.

[twenty20 img1=”9170″ img2=”9169″ offset=”0.5″]

This work was supported by the following major funders: USAID/NASA (SERVIR), Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, and Erol Foundation.

Finer M, Villa L (2020) Amazon Fire Tracker 2020: Brazil #4 (June 17, 2020). MAAP.

As presented in MAAP #118, Amazon Conservation launched a real-time fire monitoring app that specializes in detection of elevated aerosol emissions from burning Amazon fires. As detailed below, the app detected the second major 2020 fire on June 8, 2020 in Mato Grosso, Brazil.

Step 1. Detection of elevated emissions in the southeastern Brazilian Amazon (Mato Grosso).

Step 3. Zoom in again to see precisely the fire location and obtain coordinates.

Step 4. Check the satellite imagery archive in Planet Explorer. Here is a Landsat image (30 meter resolution) showing the fire burned around 3,000 hectares (7,400 acres) of an area deforested in July 2018. Note that MAAP #113 made the important discovery that most of the 2019 Brazilian Amazon fires were burning recently deforested areas (and not uncontrolled forest fires).![]()

Coordinates

This work was supported by the following major funders: USAID/NASA (SERVIR), Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, and Erol Foundation.

Finer M, Villa L (2020) Amazon 2020 Fire Tracker #2 – Brazil, June 8. MAAP.

The Brazilian Amazon fires made international headlines last year.

By analyzing an archive of satellite imagery (from Planet Explorer), we made the major discovery that many of the 2019 fires were actually burning recently deforested areas (MAAP #113). In fact, many of the fires were burning areas deforested earlier that same year of 2019.

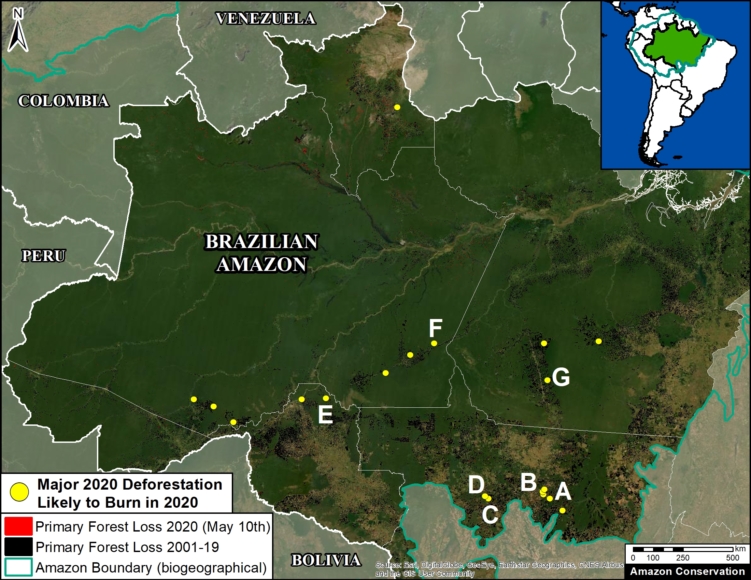

Thus, we may predict 2020 fire locations based on identifying major deforestation events in the early months of this year.

Using a novel methodology*, we estimate the deforestation of over 150,000 hectares (373,240 acres) of primary forest in the Brazilian Amazon thus far in 2020 (through May 25). Thus, there is high potential for another intense fire season.

Below, we illustrate the process of predicting 2020 fires based on recent deforestation.

Note: In MAAP #118 we just reported that the first major fires of 2020 were in fact burning recently deforested areas (2018-19).

In the Base Map, the yellow dots indicate the largest new deforestation events that we predict are likely 2020 fire locations. See below for satellite imagery examples (letters A-G). Two of the likely fire points are within protected areas (see Annex).

Below is a series of images showing the major deforestation events of 2020 that we predict are likely upcoming fire locations (see letters A-G on the Base Map above for context). The red arrows point to the major deforestation events. Note that all of the deforestation areas are surrounded by primary forest that could be impacted if fires escape. Also note that several deforestation areas are quite large, over 2,000 hectares (5,000 acres).

Zoom A shows the deforestation of 775 hectares (1,915 acres) between January (left panel) and May 2020 (right panel), in the state of Mato Grosso.

Zoom B shows the deforestation of 205 hectares (510 acres) between January (left panel) and May 2020 (right panel), in the state of Mato Grosso.

Zoom C shows the deforestation of 395 hectares (980 acres) between January (left panel) and May 2020 (right panel), in the state of Mato Grosso.

Zoom D shows the deforestation of 300 hectares (735 acres) between January (left panel) and May 2020 (right panel), in the state of Mato Grosso.

Zoom E shows the deforestation of 840 hectares (2,075 acres) between January (left panel) and April 2020 (right panel), in the state of Rondônia.

Zoom F shows the deforestation of 2,395 hectares (5,920 acres) between January (left panel) and May 2020 (right panel), in the state of Amazonas.

Zoom G shows the deforestation of 5,990 hectares (14,800 acres) between January (left panel) and May 2020 (right panel), in the state of Pará.

World Eckert IV (Decimal Degrees) (X,Y)

Zoom A: -54.862624, -11.971904

Zoom B: -55.087026, -11.836788

Zoom C: -56.999405, -11.979054

Zoom D: -57.128192, -11.896948

Zoom E: -62.658907, -8.477944

Zoom F: -58.892358, -6.567775

Zoom G: -54.948419, -7.853721

The July – September 2020 forecast points to an active fire season in most of the western Amazon – much of central and southern Peru, northern Bolivia and the Brazilian states of Acre and Rondônia. This year’s forecast indicates an active fire season of similar magnitude to those of 2005 and 2010, when widespread fires were observed in the region.

To more information check:https://firecast.cast.uark.edu/

*We developed a novel methodology to estimate deforestation of primary forest in the Brazilian Amazon. For 2020 data, we merged confirmed GLAD alerts (University of Maryland) with select DETER alerts from the Brazilian space agency (INPE). This methodology takes advantage of the higher resolution of the GLAD alerts (30 meters vs 64 meters from DETER), but also the national expertise of the Brazilian government.

For the DETER data, we used the three deforestation and mining categories (DESMATAMENTO CR, DESMATAMENTO Vegetal, and MINERACAO). We avoided overlapping areas with the GLAD alerts.

Finally, we filtered the data for only primary forest loss. For our estimate of primary forest loss, we intersected the forest cover loss data with the additional dataset “primary humid tropical forests” as of 2001 (Turubanova et al 2018). We also removed all previous forest loss data 2001-19.

We thank J. Beavers, S. Novoa, K. Fernandes, and G. Palacios for helpful comments to earlier versions of this report.

This work was supported by the following major funders: Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, and Erol Foundation.

Finer M, Mamani N (2020) Deforestation and Fires in the Brazilian Amazon – 2020. MAAP:

A tempo para a próxima temporada de incêndios, estamos relançando uma versão aprimorada do nosso aplicativo de monitoramento de incêndios em tempo real da Amazon , hospedado pelo Google Earth Engine.

Quando os incêndios queimam, eles emitem gases e aerossóis.* Um novo satélite (Sentinel-5P da Agência Espacial Europeia) detecta essas emissões de aerossóis .*

O principal recurso do aplicativo é a identificação fácil de usar e em tempo real de grandes incêndios na Amazônia, com base nas emissões de aerossóis detectadas pelo Sentinel-5P.

Como os dados são atualizados diariamente e não são impactados por nuvens, o monitoramento em tempo real realmente é possível. Nossa meta é carregar a nova imagem de cada dia até a meia-noite.

Usando o aplicativo, identificamos recentemente o primeiro grande incêndio na Amazônia de 2020 em 28 de maio, no estado do Mato Grosso, no Brasil. Ele estava queimando uma área recentemente desmatada em julho de 2019.

Abaixo, fornecemos instruções sobre como usar o aplicativo, usando o incêndio de 28 de maio como exemplo.

Etapa 1. Abra o aplicativo de monitoramento de incêndios em tempo real , hospedado pelo Google Earth Engine. Examine a Amazônia em busca de emissões de aerossóis de grandes incêndios (indicados em amarelo, laranja e vermelho ). Neste caso, identificamos emissões elevadas no sudeste da Amazônia brasileira (em 28 de maio de 2020).

Etapa 3. Aumente o zoom nas emissões de aerossóis.

Etapa 4. Ajuste (deslize para baixo) a transparência da camada de emissões para ver os alertas de incêndio subjacentes . Usamos os alertas para localizar a fonte das emissões (veja o círculo roxo). Obtenha as coordenadas dos alertas clicando no mapa e, em seguida, verificando a barra “Coordenadas” à esquerda (abaixo das Instruções).

Etapa 5. Entramos com as coordenadas no Planet Explorer e encontramos uma imagem de alta resolução para o mesmo dia (28 de maio), confirmando o primeiro grande incêndio na Amazônia de 2020. A área queimada foi de 357 hectares (882 acres).

Usando o arquivo Planet, descobrimos que essa área exata foi desmatada entre julho e agosto de 2019 e depois queimada em maio de 2020. Isso se encaixa em nossa descoberta importante recente de que muitos incêndios na Amazônia brasileira estão, na verdade, queimando áreas recentemente desmatadas ( MAAP #113 ). Para mais informações sobre como prever incêndios futuros com base no desmatamento recente, consulte MAAP #119 .

A previsão de julho a setembro de 2020 aponta para uma temporada ativa de incêndios na maior parte da Amazônia ocidental – grande parte do centro e sul do Peru, norte da Bolívia e os estados brasileiros do Acre e Rondônia. A previsão deste ano indica uma temporada ativa de incêndios de magnitude semelhante às de 2005 e 2010, quando incêndios generalizados foram observados na região.

Para mais informações, consulte: https://firecast.cast.uark.edu/

Agradecemos a E. Ortiz, S. Novoa, K. Fernandes, G. Palacios pelos comentários úteis às versões anteriores deste relatório.

Este trabalho foi apoiado pelos seguintes financiadores principais: USAID/NASA (SERVIR), Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI), Agência Norueguesa para Cooperação para o Desenvolvimento (NORAD), Fundo Internacional de Conservação do Canadá (ICFC), Metabolic Studio e Erol Foundation.

Finer M, Villa L, Mamani N (2020) Aplicativo de monitoramento de incêndios na Amazônia em tempo real. MAAP: #118.

We present the second part of our series on Amazon gold mining, with a focus on the Brazil*

Specifically, we focus on mining in indigenous territories in the Brazilian Amazon.

Extractive activities, such as gold mining, are constitutionally not permitted on indigenous lands, but the Bolsonaro administration is advancing a bill (PL 191) that would reverse this.

The Base Map indicates three Brazilian indigenous territories where we identified recent major gold mining deforestation:

We documented the gold mining deforestation of 10,245 hectares (25,315 acres) across all three indigenous territories over the past three years (2017 – 2019). That is the equivalent of 14,000 soccer fields.

Below, see more detailed data, including a series of satellite GIFs of the recent gold mining deforestation in each territory.

*Part 1 looked at the Peruvian Amazon (see MAAP #115). For information on Suriname, see this report from Amazon Conservation Team. For all other countries see this resource from RAISG.

In 2019, all three territories experienced an increase in gold mining deforestation.

In Munduruku Territory, we documented the loss of 3,456 hectares due to mining activity between 2017 and 2019. Note the major spike in 2019, where mining deforestation reached 2,000 hectares.

In Kayapó Territory, we documented the loss of 5,614 hectares between 2017 and 2019. Note that mining deforestation also reached 2,000 hectares in 2019.

In Yanomami Territory, we documented the loss of 1,174 hectares between 2017 and 2019. Note that mining deforestation reached 500 hectares in 2019.

Overall, 44% (4,500 hectares) of the gold mining deforestation occurred in 2019, indicating an increasing trend.

The GIF below shows an example of gold mining deforestation in Munduruku Territory between 2017 and 2019.

The GIF below shows an example of gold mining deforestation in Kayapó Territory between 2017 and 2019.

The GIF below shows an example of gold mining deforestation in Yanomami Territory between 2017 and 2019.

Below see detailed gold mining deforestation maps for all three Brazilian indigenous territories detailed in this report. Click each image to enlarge.

We thank S. Novoa (ACCA), V. Guidotti de Faria (Imaflora), and G. Palacios for helpful comments to earlier versions of this report.

This work was supported by the following major funders: Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, and Erol Foundation.

Finer M, Mamani N (2020) Amazon Gold Mining, part 2: Brazil. MAAP: 116.

MAAP, an initiative of Amazon Conservation, specializes in satellite-based, real-time deforestation monitoring of the Amazon. Our geographic focus covers five countries: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru (see Base Map).

We found that, since 2001, this vast area lost 65.8 million acres (26.6 million hectares) of primary forest, an area equivalent to the size of the United Kingdom (or the U.S. state of Colorado).

In 2019, we published 18 high-impact reports on the most urgent cases of deforestation. 2019 highlights include:

Here, in our annual Synthesis Report, we go beyond these emblematic cases and look at the bigger picture for 2019, describing the most important deforestation trends and hotspots across the Amazon.

*Note: to download a PDF, click the “Print” button below the title.

The following GIF shows deforestation trends for each country between 2001 and 2019 (see descriptive notes below). Click here for static versions of each graph.

Three important points about the data: First, as a baseline, we use annual forest loss from the University of Maryland to have a consistent source across all five countries (thus it may differ from official national data). Second, we applied a filter to only include loss of primary forest (see Methodology). Third, the 2019 data represents a preliminary estimate based on early warning alerts.

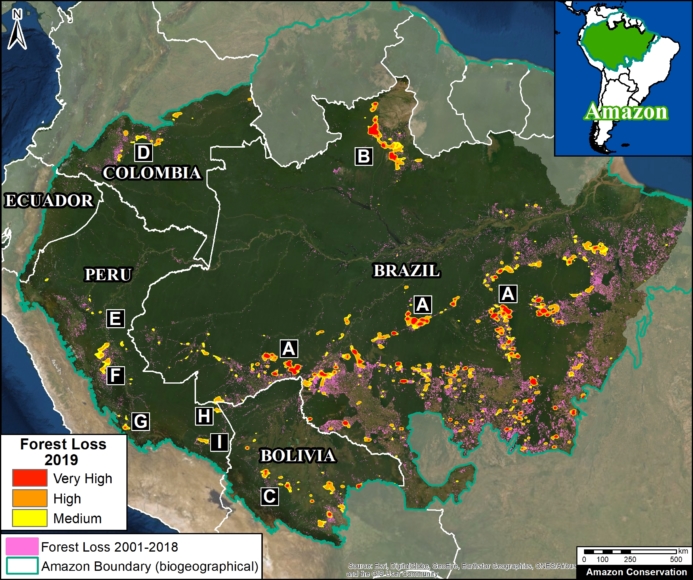

The Base Map shows the most intense deforestation hotspots during 2019.

Many of the major deforestation hotspots were in Brazil. The letters A indicate areas deforested between March and July, and then burned starting in August, covering over 735,000 acres in the states of Rondônia, Amazonas, Mato Grosso, Acre, and Pará (MAAP #113). They also indicate areas where fire escaped into the surrounding primary forest, impacting an additional 395,000 acres. There is a concentration of these hotspots along the Trans-Amazonian Highway. The letter B indicates uncontrolled forest fires earlier in the year (March) in the state of Roraima (MAAP #109).

Bolivia also had an intense 2019 fire season. Letter C indicates the area where fires in Amazonian savanna ecosystems escaped to the surrounding forests.

In Colombia, the letter D indicates an area of high deforestation surrounding and within four protected areas: Tinigua, Chiribiquete, and Macarena National Parks, and the Nukak National Reserve (MAAP #106).

In Peru, there are several key areas to highlight. Letter E indicates a new Mennonite colony that has caused the deforestation of 2,500 acres in 2019, near the town of Tierra Blanca in the Loreto region (MAAP #112). Letter F indicates an area of high concentration of small-scale deforestation in the central Amazon (Ucayali and Huánuco regions), with cattle ranching as one of the main causes (MAAP #37). Letter G indicates an area of high concentration of deforestation along the Ene River (Junín and Ayacucho regions). In the south (Madre de Dios region), letter H indicates expanding agricultural activity around the town of Iberia (MAAP #98) and letter I indicates deforestation caused by a combination of gold mining and agricultural activity.

As noted above, there are three important considerations about the data in our analysis: First, as a baseline, we use annual forest loss from the University of Maryland to have a consistent source across all five countries. Thus, the values may differ from official national data. Second, we applied a filter to only include loss of primary forest in order to better approximate the official methodology and data. Third, the 2019 data represents a preliminary estimate based on early warning alerts.

The baseline forest loss data presented in this report were generated by the Global Land Analysis and Discovery (GLAD) laboratory at the University of Maryland (Hansen et al 2013) and presented by Global Forest Watch. Our study area is strictly what is highlighted in the Base Map.

Specifically, for our estimate of forest cover loss, we multiplied the annual “forest cover loss” data by the density percentage of the “tree cover” from the year 2001 (values >30%).

For our estimate of primary forest loss, we intersected the forest cover loss data with the additional dataset “primary humid tropical forests” as of 2001 (Turubanova et al 2018). For more details on this part of the methodology, see the Technical Blog from Global Forest Watch (Goldman and Weisse 2019).

All data were processed under the geographical coordinate system WGS 1984. To calculate the areas in metric units the UTM (Universal Transversal Mercator) projection was used: Peru and Ecuador 18 South, Colombia 18 North, Western Brazil 19 South and Bolivia 20 South.

Lastly, to identify the deforestation hotspots, we conducted a kernel density estimate. This type of analysis calculates the magnitude per unit area of a particular phenomenon, in this case forest cover loss. We conducted this analysis using the Kernel Density tool from Spatial Analyst Tool Box of ArcGIS. We used the following parameters:

Search Radius: 15000 layer units (meters)

Kernel Density Function: Quartic kernel function

Cell Size in the map: 200 x 200 meters (4 hectares)

Everything else was left to the default setting.

For the Base Map, we used the following concentration percentages: Medium: 10%-20%; High: 21%-35%; Very High: >35%.

Goldman L, Weisse M (2019) Explicación de la Actualización de Datos de 2018 de Global Forest Watch. https://blog.globalforestwatch.org/data-and-research/blog-tecnico-explicacion-de-la-actualizacion-de-datos-de-2018-de-global-forest-watch

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. “High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change.” Science 342 (15 November): 850–53. Data available on-line from: http://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest.

Planet Team (2017). Planet Application Program Interface: In Space for Life on Earth. San Francisco, CA. https://api.planet.com

Turubanova S., Potapov P., Tyukavina, A., and Hansen M. (2018) Ongoing primary forest loss in Brazil, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Indonesia. Environmental Research Letters https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/aacd1c

Agradecemos a S. Novoa (ACCA), R. Botero (FCDS), A. Condor (ACCA) y G. Palacios por sus útiles comentarios a este reporte.

We thank S. Novoa (ACCA), R. Botero (FCDS), A. Condor (ACCA), A. Folhadella (Amazon Conservation), M. Cohen, and G. Palacios for helpful comments to earlier versions of this report.

This work was supported by the following major funders: NASA/USAID (SERVIR), Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, International Conservation Fund of Canada (ICFC), Metabolic Studio, Erol Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, and Global Forest Watch Small Grants Fund (WRI).

Finer M, Mamani N (2020) MAAP Synthesis: 2019 Amazon Deforestation Trends and Hotspots. MAAP Synthesis #4.