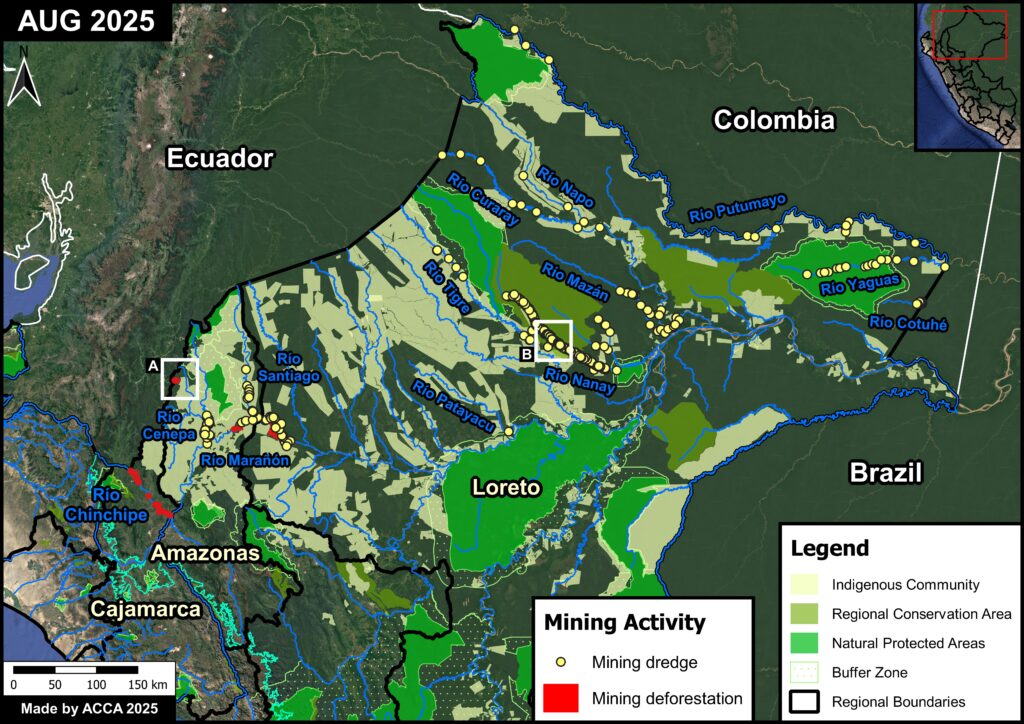

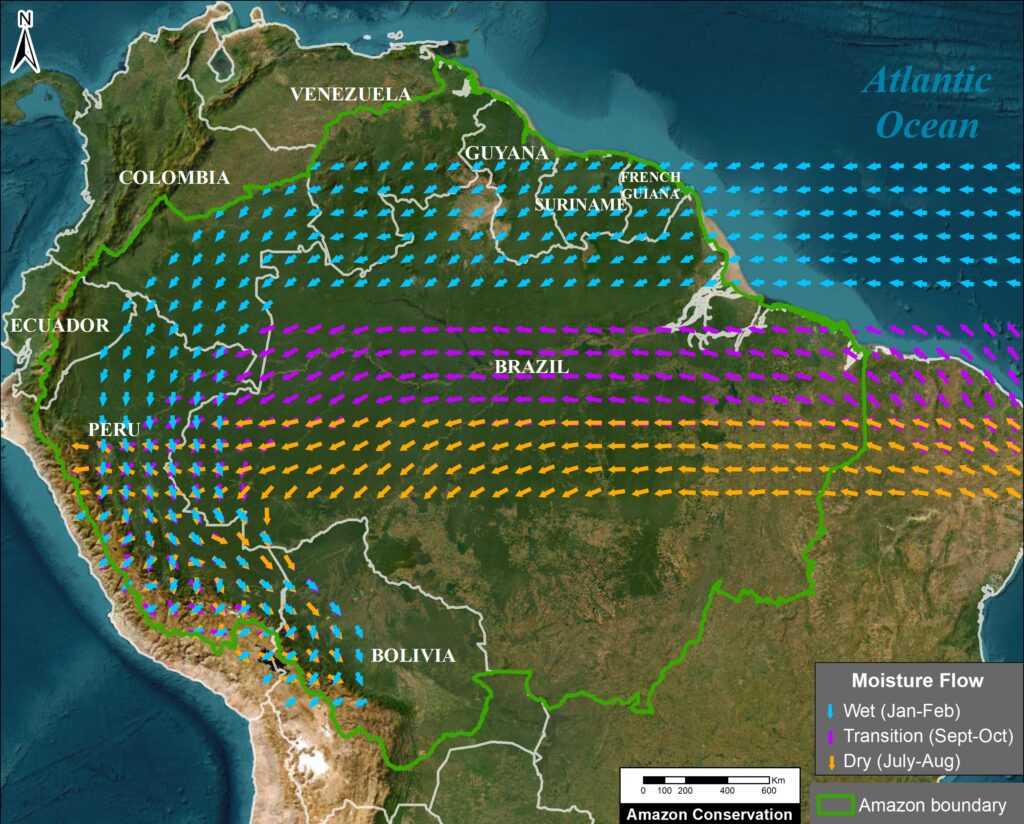

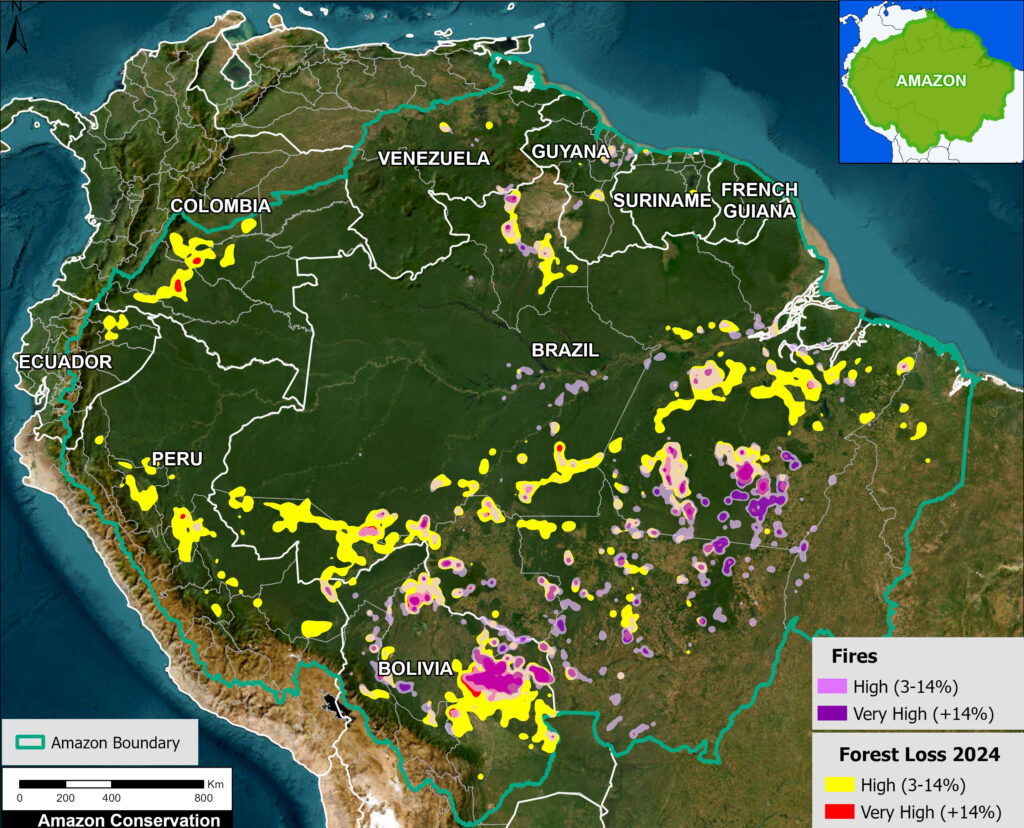

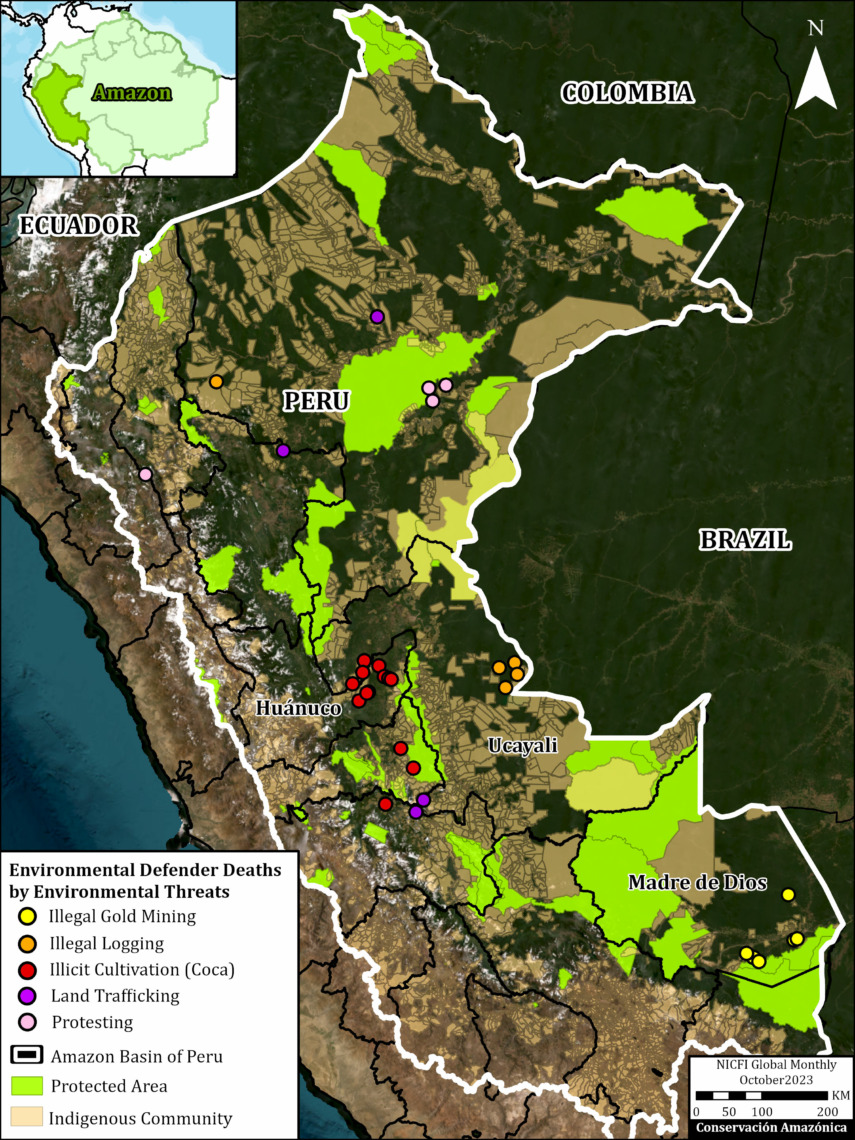

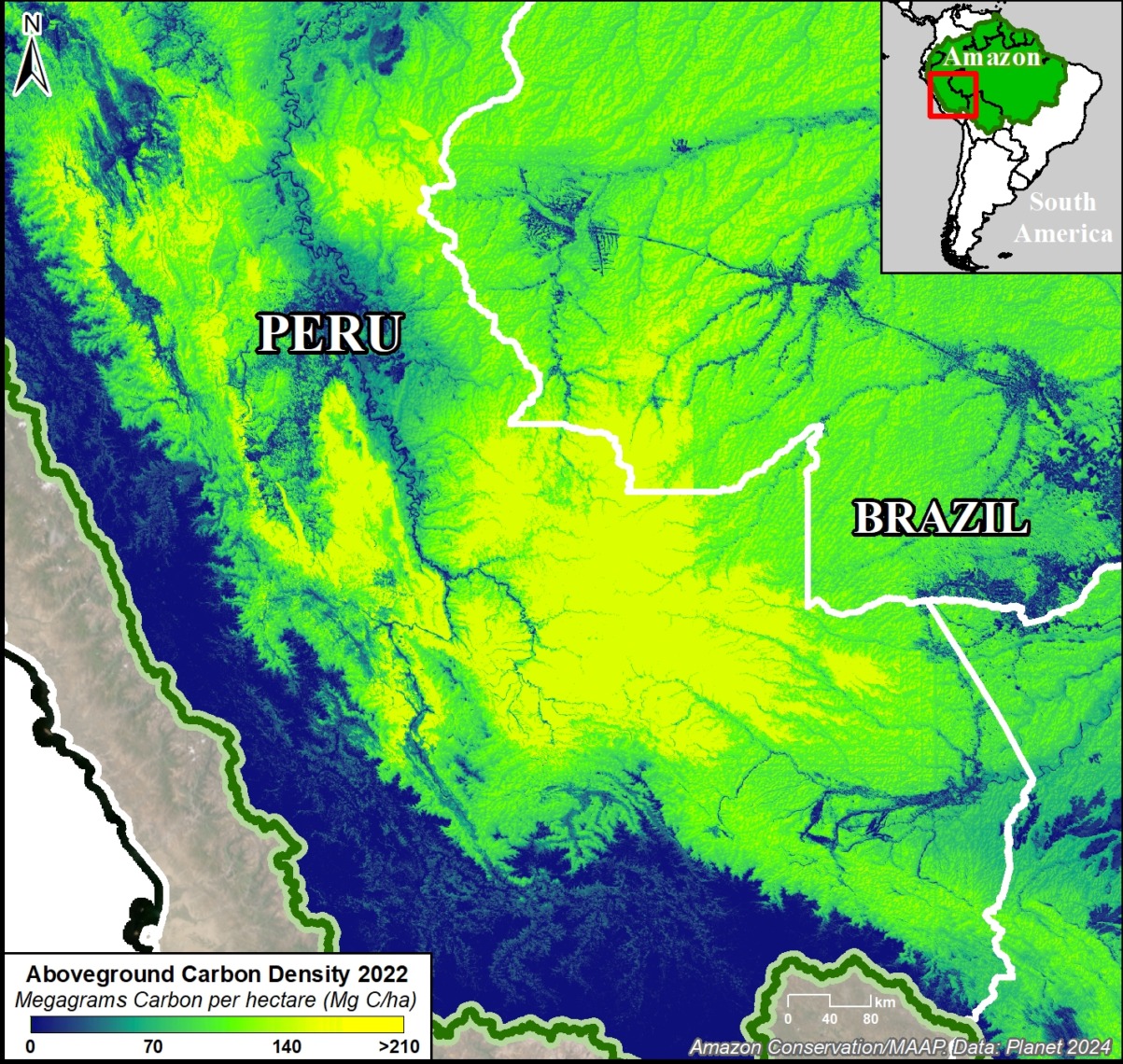

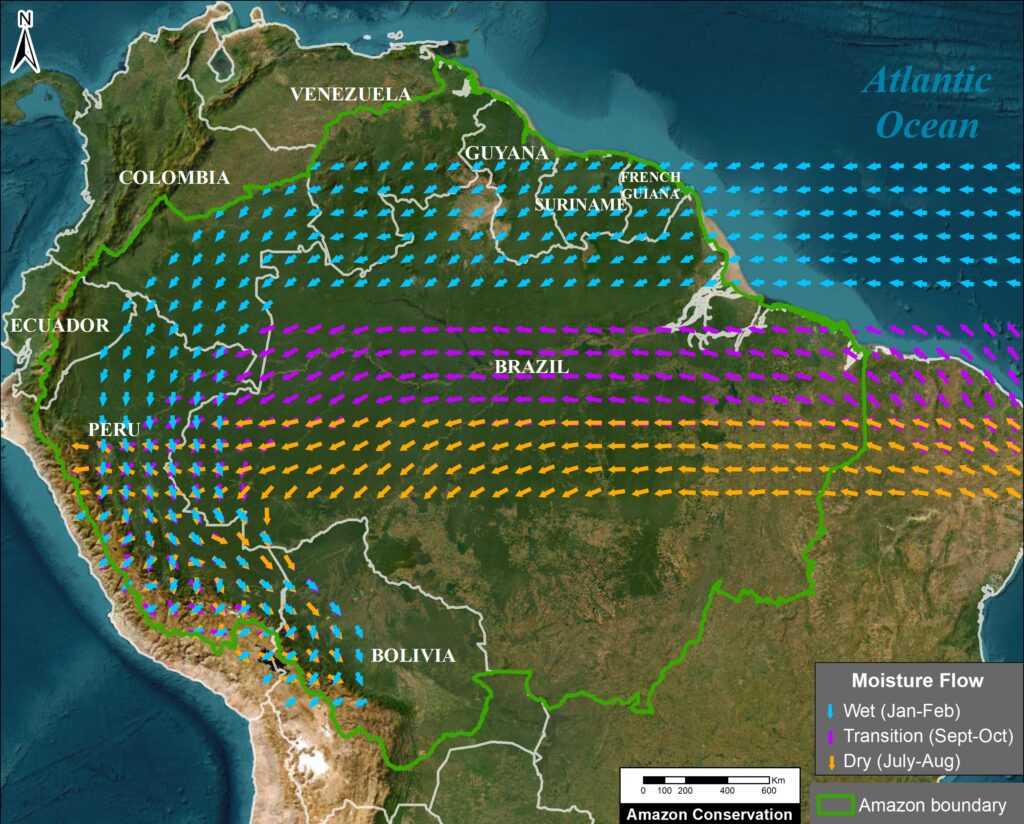

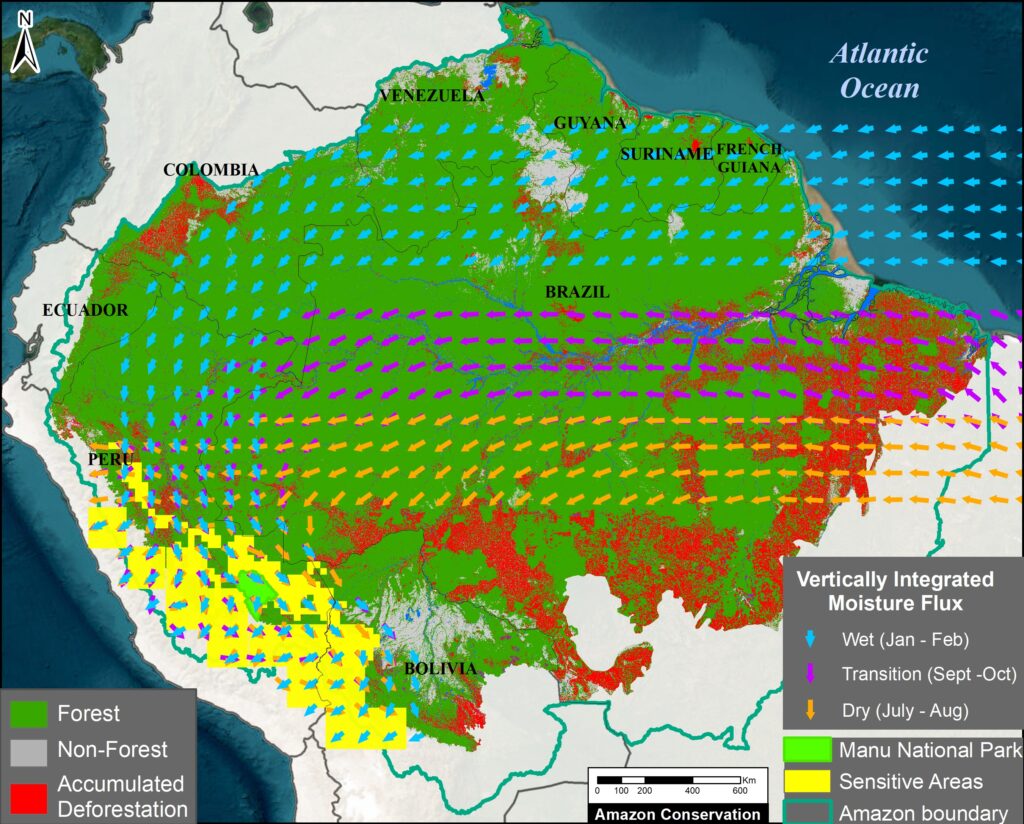

Intro Map. Amazon moisture flow (aerial river) for the southwest Amazon. Source: Amazon Conservation/MAAP

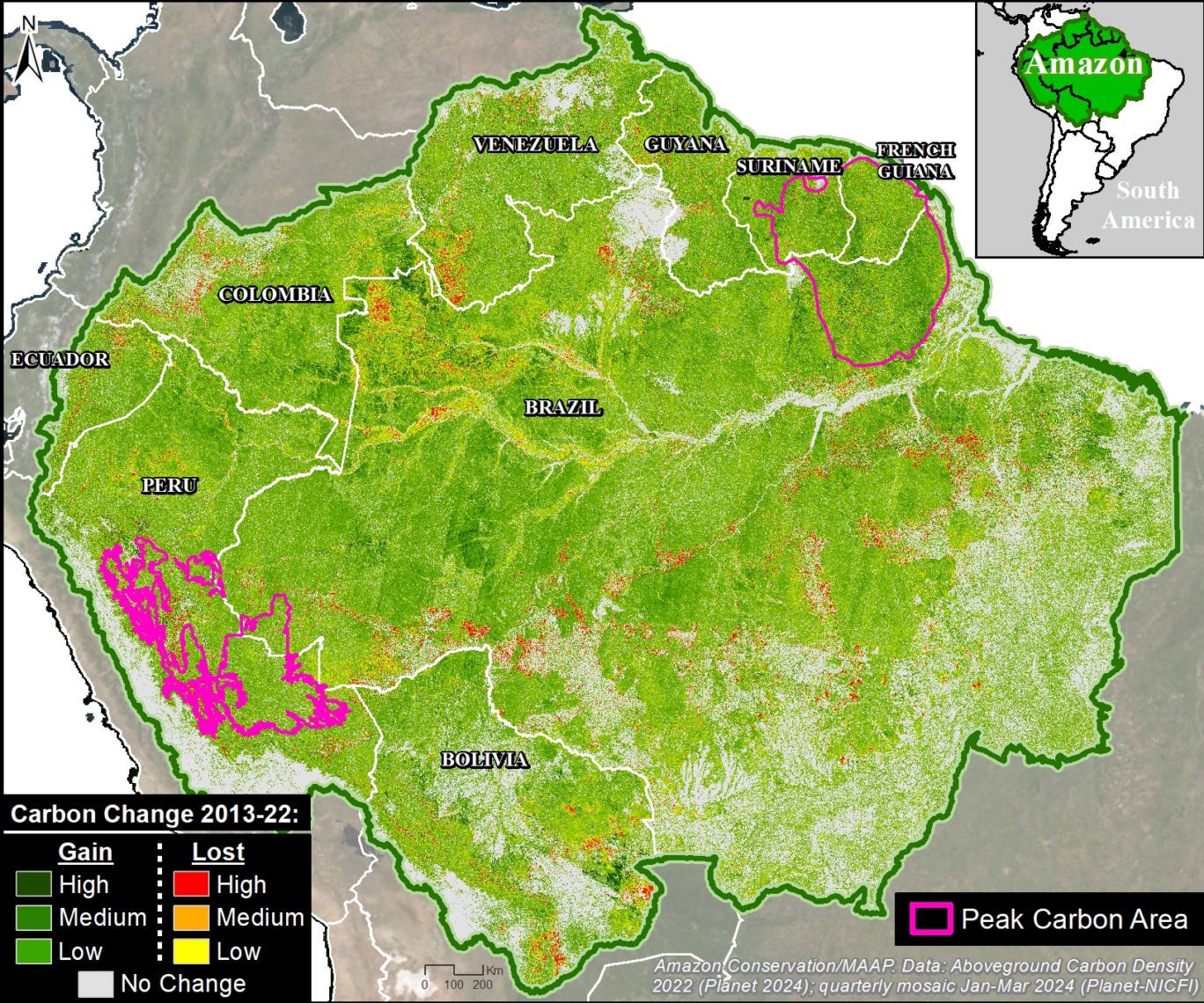

The Amazon biome, stretching over a vast area across nine countries in northern South America, is renowned for its extreme diversity (biological and cultural) and its abundant water resources. Indeed, the major features of the Amazon are linked by interconnected water flows, both on land and in the air (Beveridge et al. 2024).

The natural phenomenon of aerial moisture transport and recycling, also known as “aerial rivers” and popularized in the press as “flying rivers,” has emerged as an essential concept related to the conservation of the Amazon. In short, moisture flows from the Atlantic Ocean across the Amazon, uniquely facilitated by the rainforest itself. As they move westward, these flying rivers drop water onto the forest below. The forest subsequently transpires moisture back into them, thus recycling water and supporting rainforest ecosystems far from the Ocean source. For example, the Intro Map illustrates the aerial river for the southwest Amazon.

Continued deforestation and forest degradation, however, will disrupt and diminish the critical east-to-west aerial water flow, inducing a “tipping point” of impacted regions that would transition from rainforest to drier savannah ecosystems.

In this report, we aim to both summarize the current state of knowledge on the movement of atmospheric moisture across the Amazon and develop novel analyses based on this information. Overall, we aim to show the critical connections between the eastern and western Amazon, and how these connections change during the major seasons (wet, dry, and transition) of the year.

Our analysis is divided into three main parts:

First, we summarize the state of knowledge on the movement of atmospheric moisture across the Amazon, drawing on a review of recent literature and exchanges with experts. Second, we identify the sensitive areas that are the most vulnerable to deforestation-caused disruption of moisture recycling. Third, we relate these sensitive areas in the west to their respective eastern key source areas for moisture for each of the three Amazonian seasons: wet, dry, and transition.

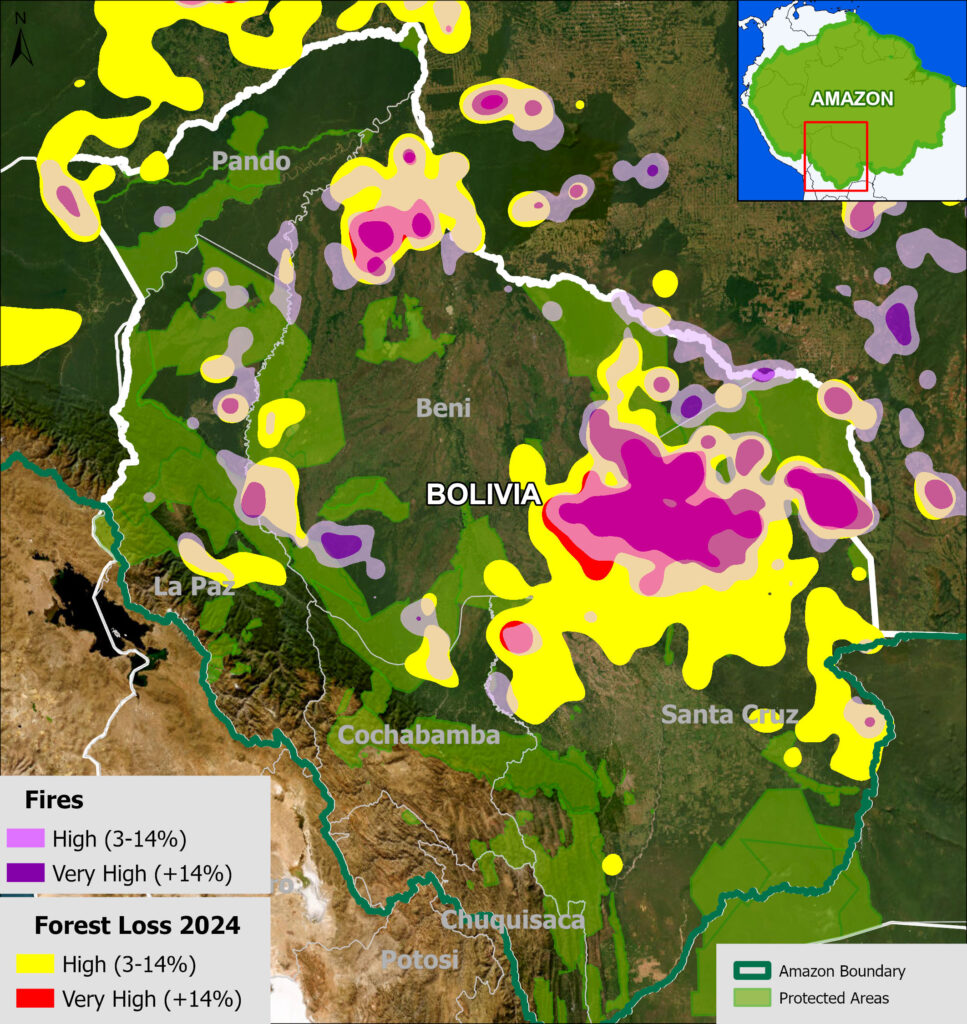

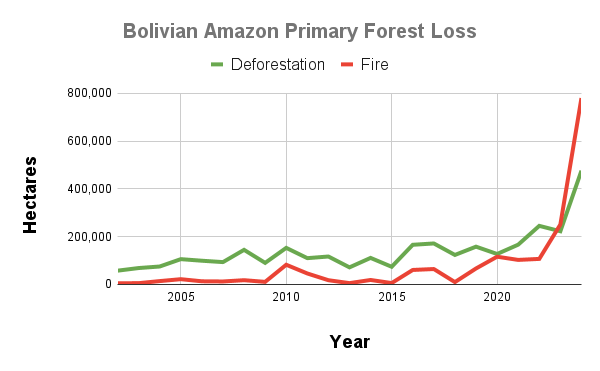

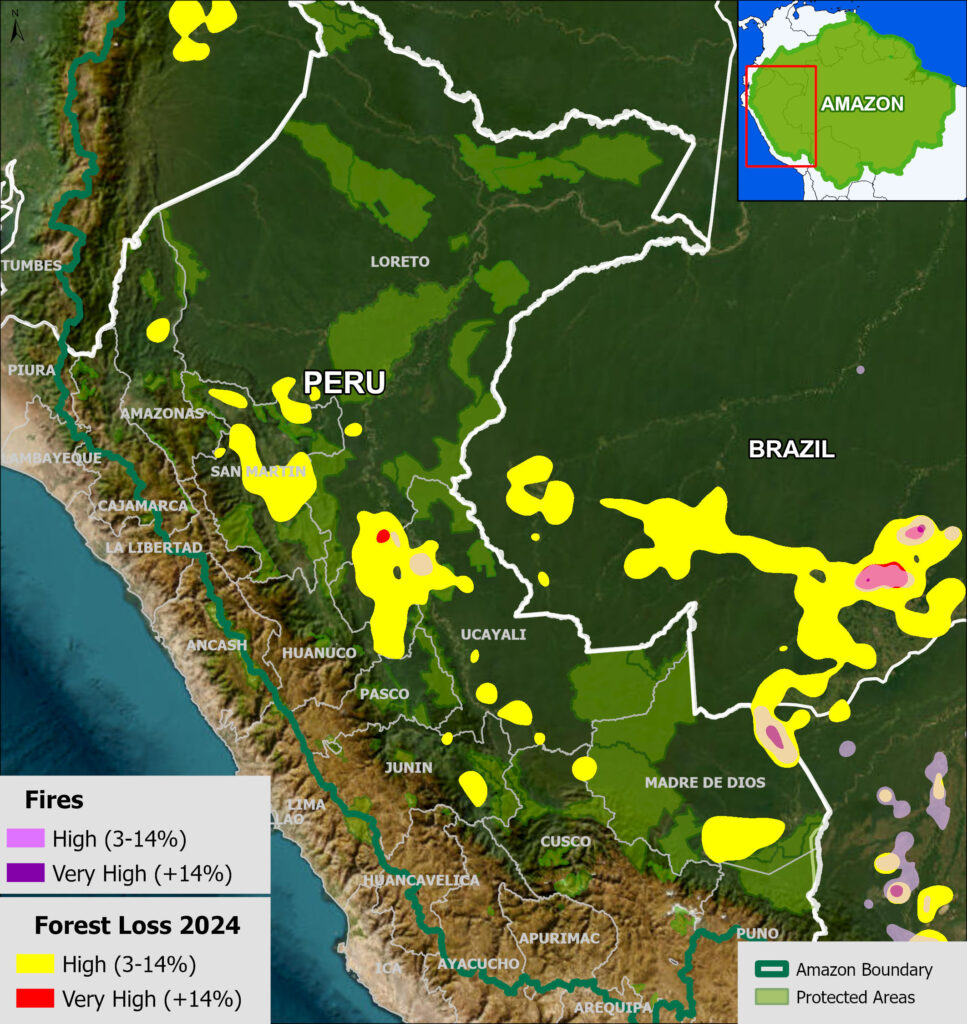

In summary, we identified the sensitive areas that are the most vulnerable to deforestation-caused disruption of moisture recycling from the Atlantic Ocean source are mostly located in the southwestern Amazon (Peru and Bolivia). For the wet season, much of the moisture flow to these sensitive areas crosses the continuous primary (non-deforested) forests of the northern Amazon. For the dry and transition seasons, however, the moisture flow to the sensitive areas must cross several major deforestation fronts located in the eastern Brazilian Amazon.

Thus, an important contribution of this work is to reveal that, contrary to the common perception that the tipping point is a single Amazon-wide event, certain parts of the Amazon are more vulnerable than others. Most notably, the southwestern Amazon (Peru and Bolivia) is most vulnerable to a possible tipping point, particularly stressed by disrupted dry season moisture flows over major deforestation fronts.

1. Movement of aerial moisture across the Amazon (moisture flow)

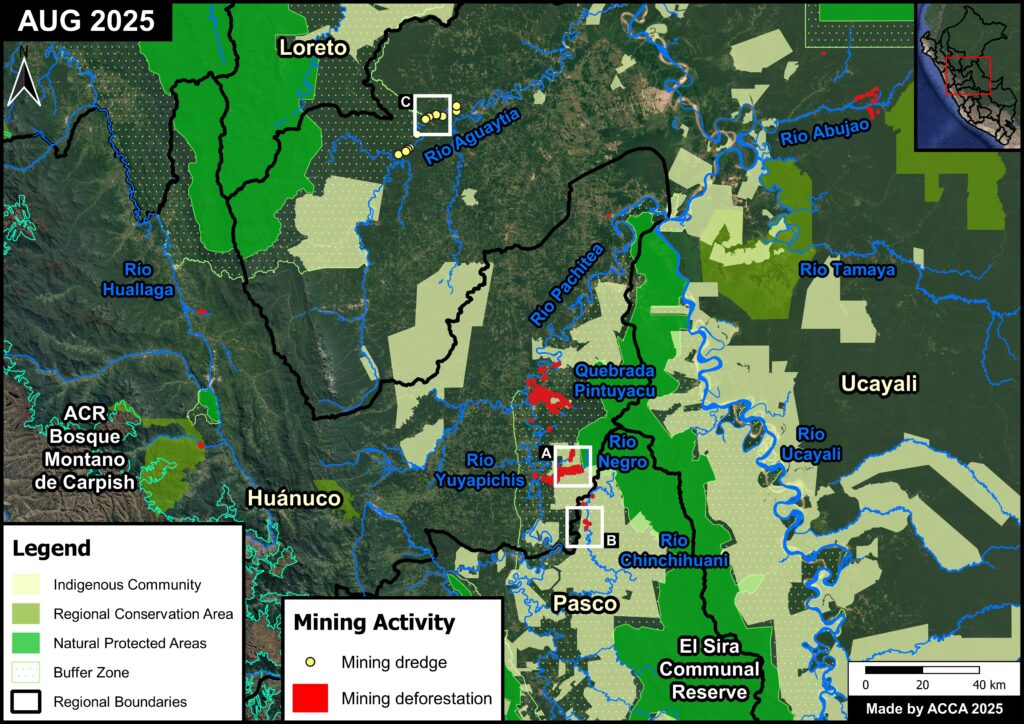

Figure 1. Amazon moisture flows by season for the SW Amazon. Data: ERA5, ACA/MAAP

Driven by permanent trade winds, aerial (atmospheric) moisture flows westward from its source in the Atlantic Ocean, across the Amazon lowlands, and toward the Andes Mountains. These moisture routes are recharged by evapotranspiration and discharged by precipitation, creating moisture recycling systems (Beveridge 2024, Weng et al. 2018, Staal 2018, Weng 2019). Evaporation recycling reloads atmospheric moisture after rainfall, while precipitation recycling removes this moisture. The Amazon forest is therefore a key component of a giant water pump, starting with water transported from the tropical Atlantic Ocean and helping push it westward (Zemp 2017, Boers 2017). Aerial rivers are the long-term and large-scale preferential pathways of the moisture flows driving this pump (Arraut et al. 2012) (see Intro Image). Thus, aerial rivers are the overall average (coarse-scale) moisture flow pattern, while moisture recycling focuses more on the seasonal differences (finer-scale).

Of all the rainfall in the Amazon, its trees have directly transpired 20% of it (Staal et al. 2018). Half of this precipitation (10%) is from moisture from one recycling event, and the other half (10%) is from multiple recycling events. This latter process of cascading precipitation, or cascading moisture recycling (Zemp et al. 2014), may happen multiple times (up to five or six), recycling water from the eastern to western Amazon, to areas increasingly distant from the Atlantic Ocean source (Lovejoy and Nobre 2019, Beveridge et al, 2024). Precipitation tends to increase exponentially as moist air travels over forests, but then drops off sharply once it moves beyond them, showing just how vital forests are in sustaining rainfall across large regions (Molina et al. 2019). Transpiration-driven moisture recycling is especially important during the dry season (Staal et al. 2018, Nehemy et al. 2025).

Thus, there are transboundary implications, as actions occurring in an eastern country can have an impact on a western country downwind of the moisture cascade. For example, deforestation in eastern Brazil can negatively impact moisture flow going to Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, including the tropical Andean mountains (Ruiz-Vasquez et al., 2020; Sierra et al. 2022, Flores et al 2024). As moisture recycling also continues beyond the boundaries of the Amazon, there may also be impacts to agricultural areas in southern Brazil, Paraguay, northern Argentina, and northern Colombia (Martinez and Dominguez 2014; Ruiz-Vasquez et al., 2020).

The resulting terrestrial flow of water from the Andes mountains through the Amazon lowlands and back to the Atlantic Ocean as runoff and flow of the Amazon river and its tributaries results in the emerging concept known as the “Andes–Amazon– Atlantic” (AAA) pathway (Beveridge et al, 2024).

Importantly, the moisture flows change seasonally in the Amazon. Figure 1 illustrates these seasonal changes for the southwest Amazon, as an example.

In the rainy season (January–February), the moisture flow is both westward and southward, creating a giant arc (Arraut 2012). Thus, the continental moisture source is the northeast Amazon (Boers 2017, Weng et al. 2018, Sierra et al. 2022).

In the dry (July–August) and the dry-to-wet transition (September-October) seasons, the moisture flow shifts more directly westward (Arraut 2012, Staal et al, 2018). Therefore, the continental moisture source is the southeast Amazon, and some studies have identified this region as the most important for maintaining overall Amazonian resilience (Zemp et al. 2017, Staal et al. 2018).

There is increasing evidence that future deforestation will reduce rainfall downwind – further west – of the moisture recycling networks, inducing a “tipping point” of impacted regions that would transition from rainforest to savannah ecosystems (Boers 2017, Staal 2018, Lovejoy & Nobre 2018). This has led to calls for forest protection strategies to maintain the cascading moisture recycling system fueling the pathway (Zemp 2017, Encalada et al. 2021). A recent review indicates limited evidence for a single, system-wide tipping point; instead, specific areas of the Amazon may be more vulnerable (Brando et al, 2025).

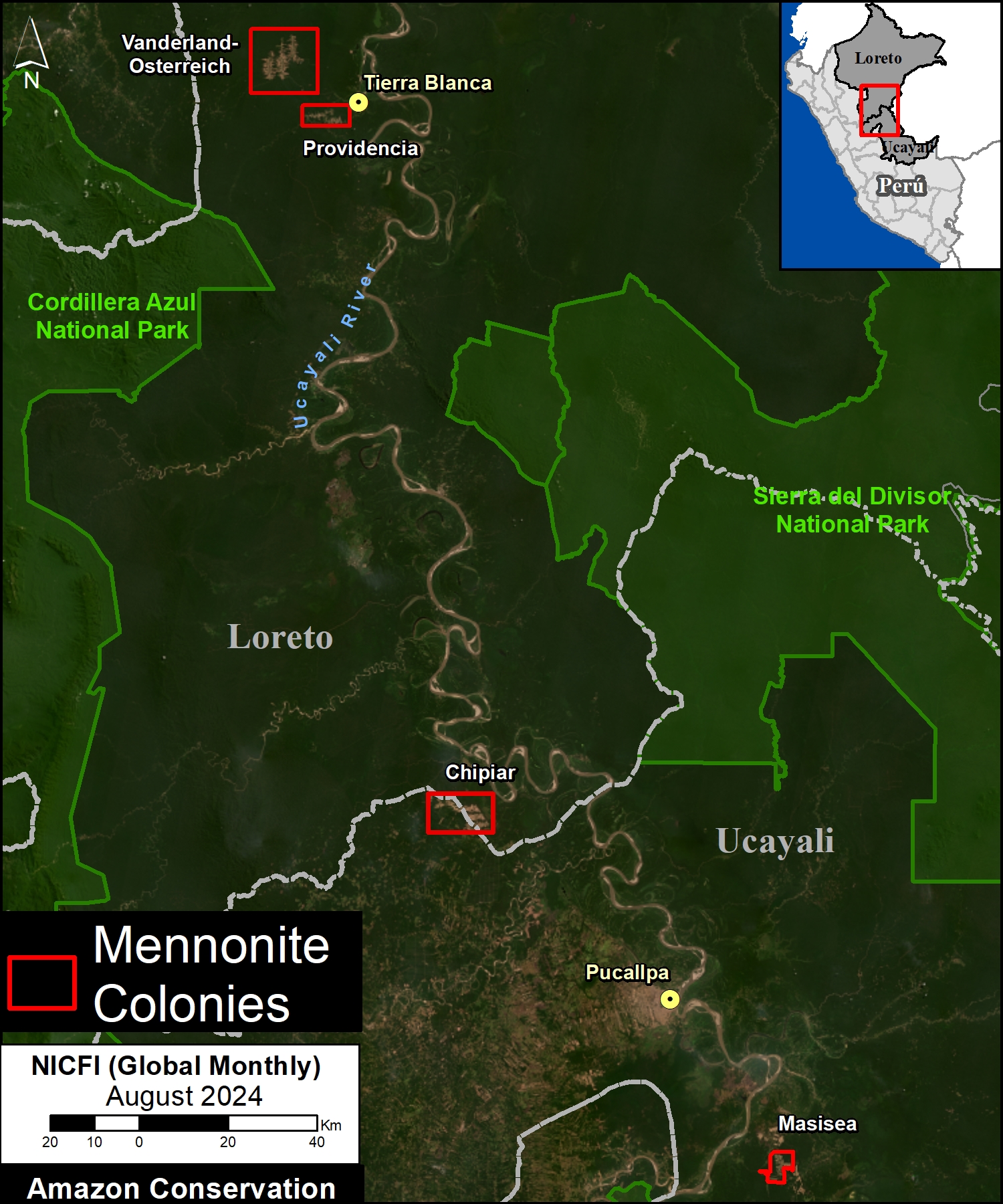

Scientists are already documenting impacts linked to increasing forest loss. Several recent studies have found that Amazon deforestation has already caused a significant decrease in precipitation in the southeast Amazon, particularly during the dry season (Qin et al, 2025, Liu et al, 2025, Franco et al. 2025). Moreover, deforestation reduces rainfall upwind of the cleared areas, impacting the western Amazon as well (Qin et al, 2025). In addition, recent studies have shown that Amazon deforestation delays the onset of the wet season in southern Amazonia (Ruiz-Vasquez et al., 2020; Commar et al., 2023; Sierra et al., 2023).

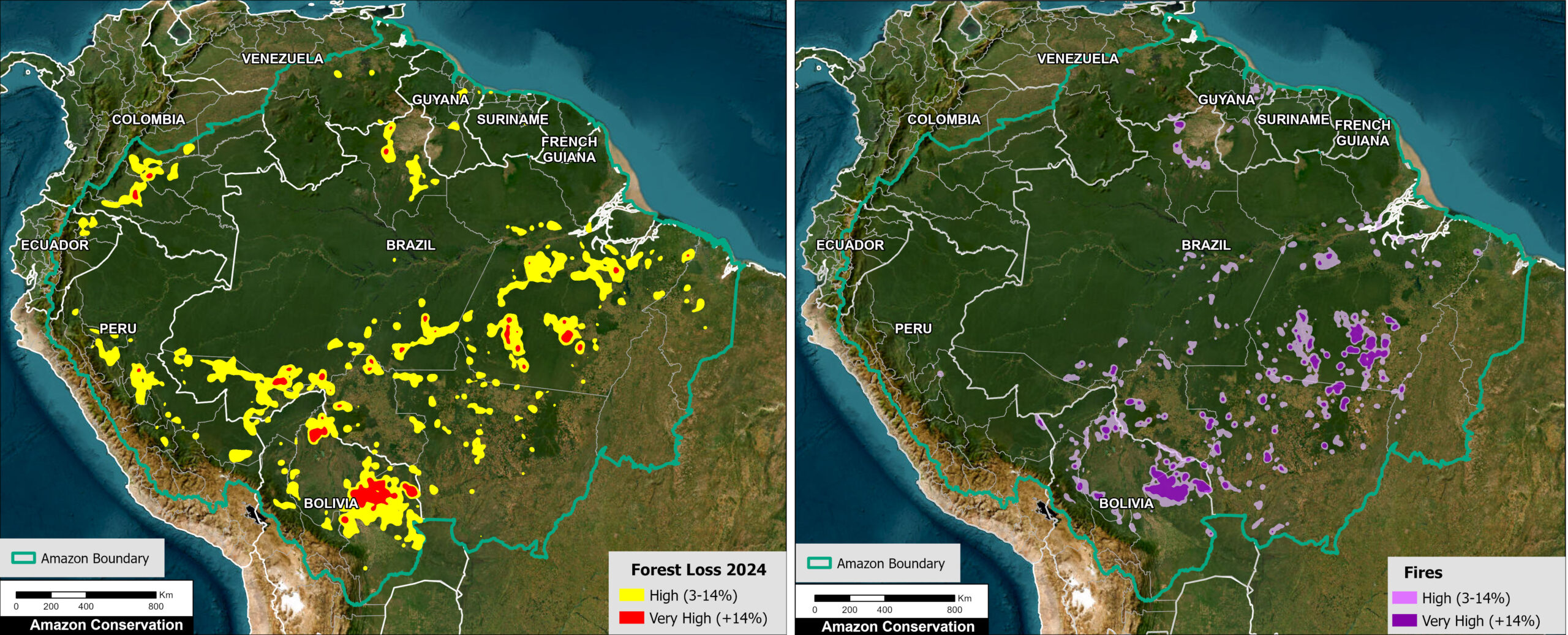

Related to deforestation, additional climatic factors, such as increased temperature and the length of the dry season, are also contributing to the tipping point (Flores et al. 2024). Multiple sources have reported on the lengthening of the dry season in southern and eastern Amazonia in recent decades, with the largest dry season observed in 2023-2024 during the major drought reported in Amazonia (Marengo el al 2024; Espinoza et al., 2024). As a result of these drier conditions, recent years have experienced record-breaking fire seasons, most notably during the El Niño years of 2016 and 2024 (Finer et al 2025). Notably, the predicted forest-to-savannah change is already happening in places experiencing increased wildfire frequency due to these hot and dry conditions (Flores et al. 2021).

2. Areas most dependent on moisture recycling in the Amazon (sensitive areas)

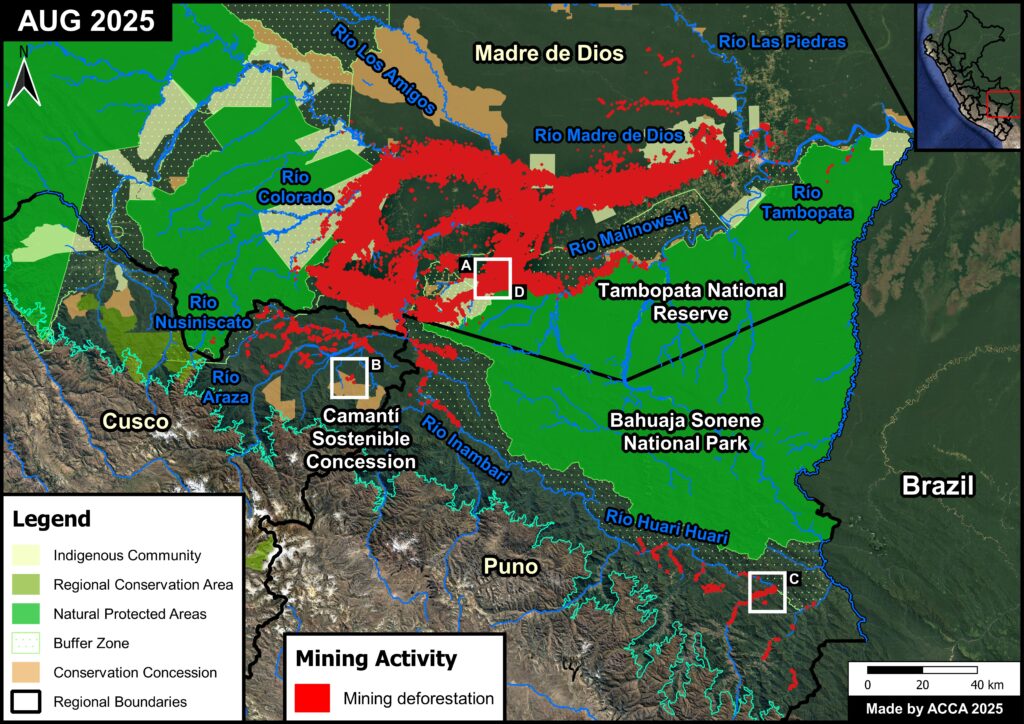

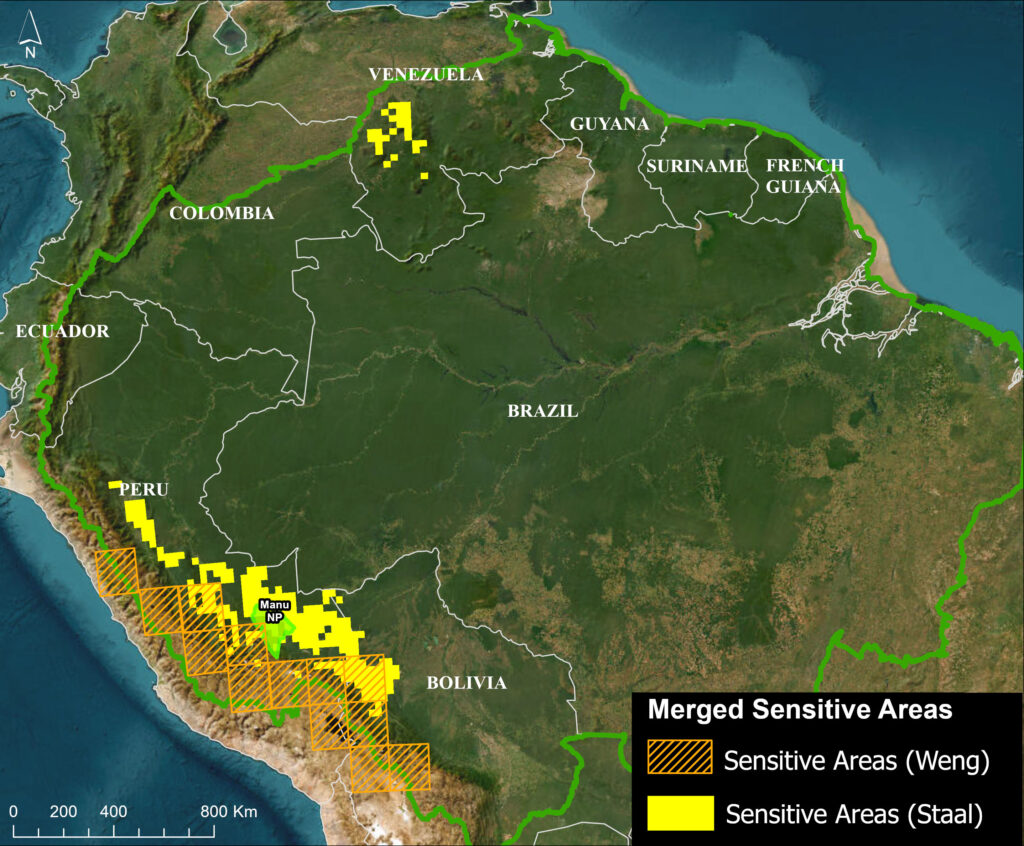

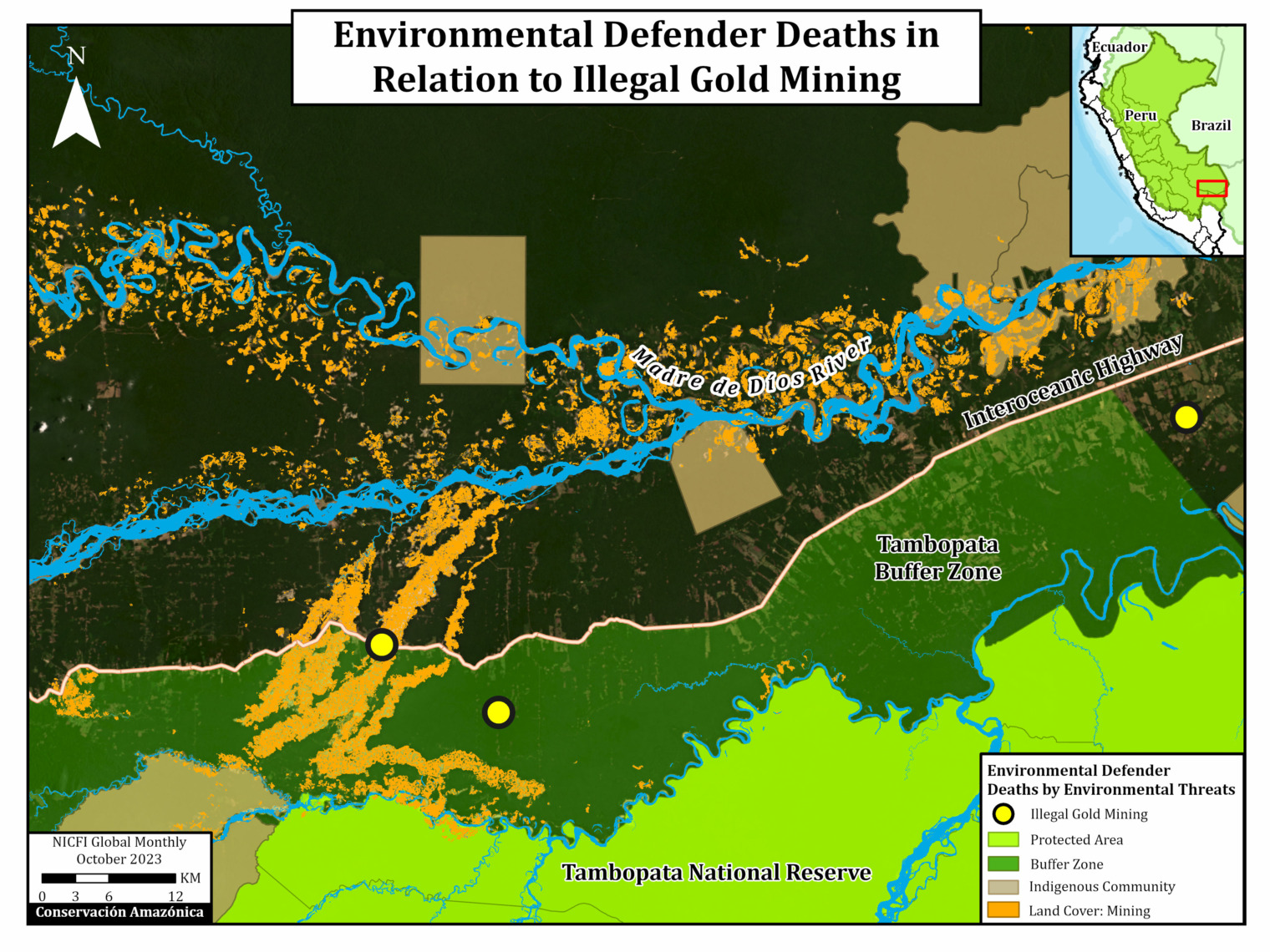

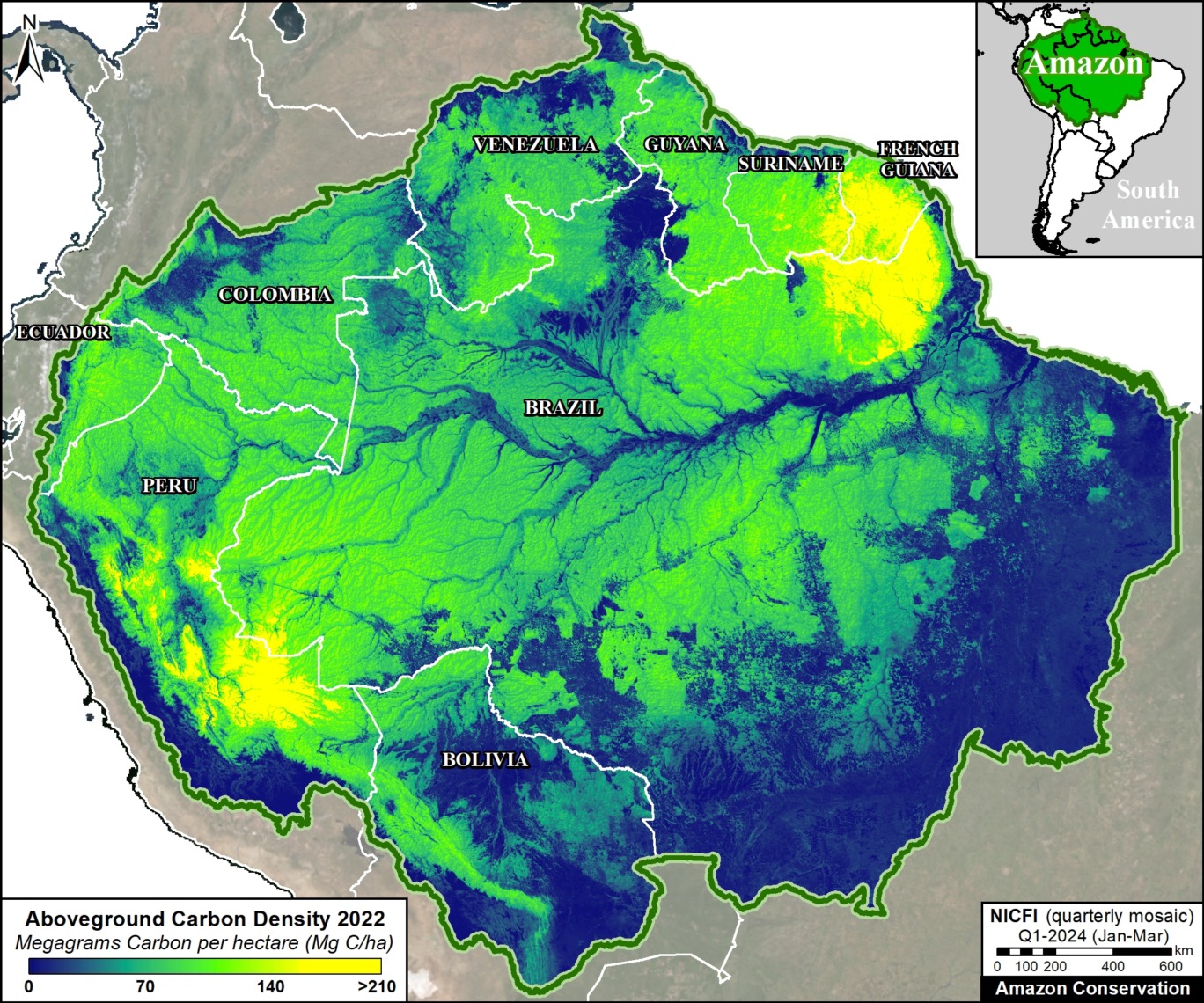

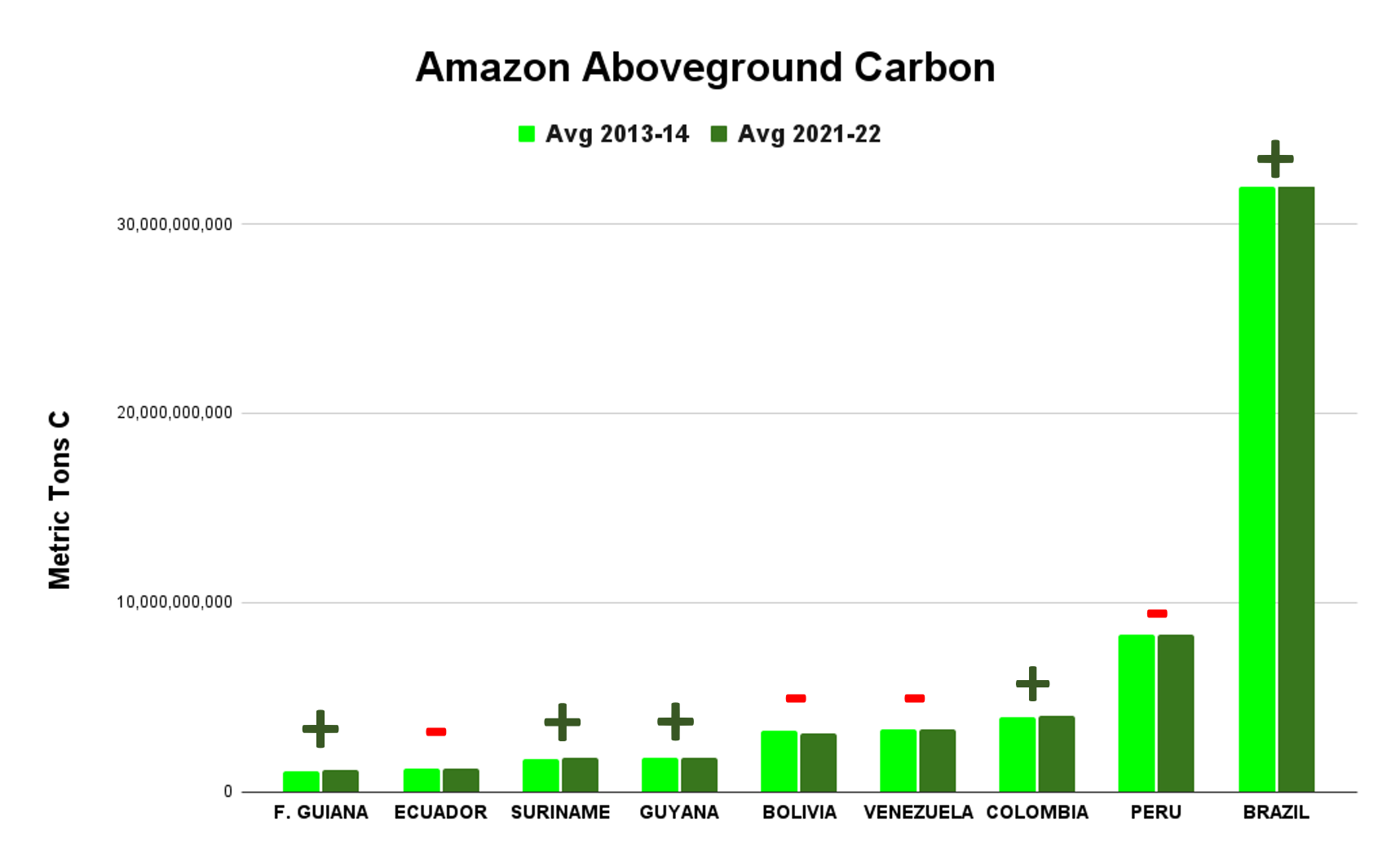

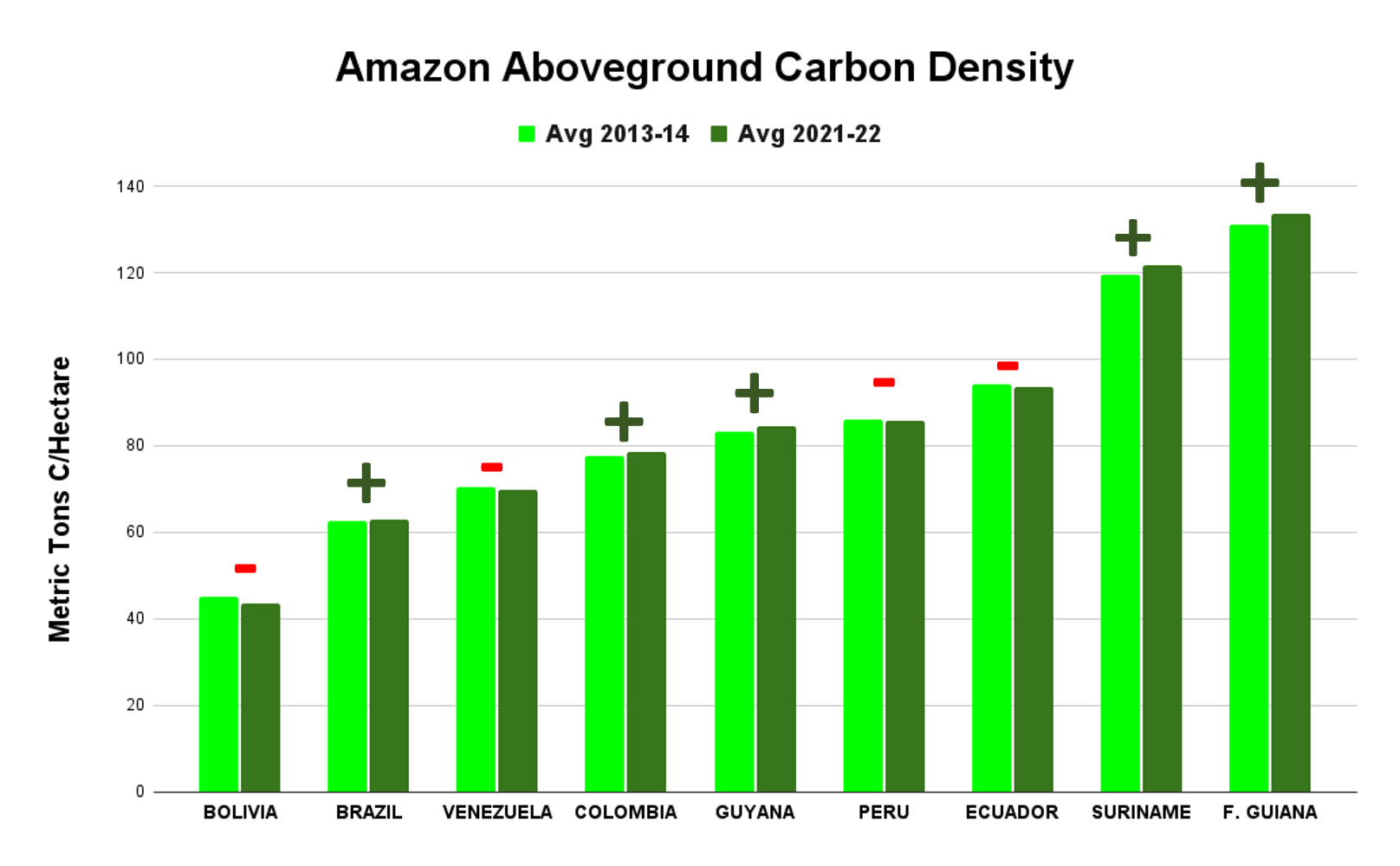

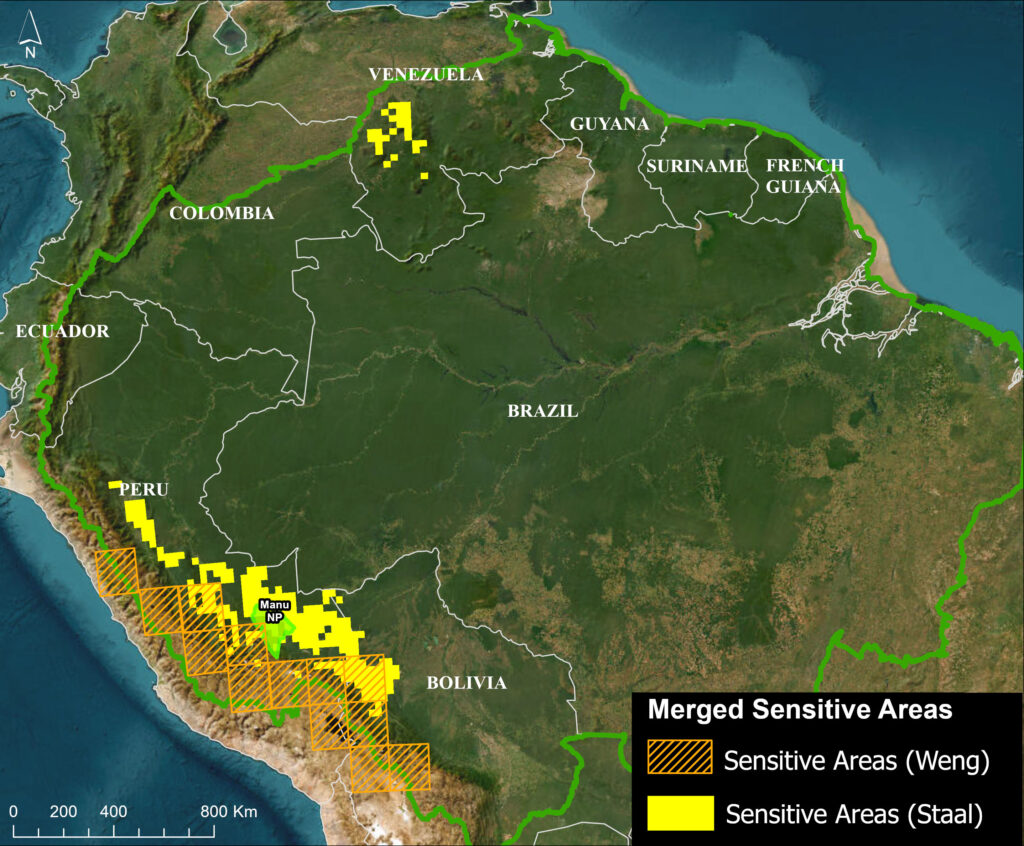

Figure 2. Merged sensitive areas. Data: Staal 2018, Weng 2018, Amazon Conservation/MAAP

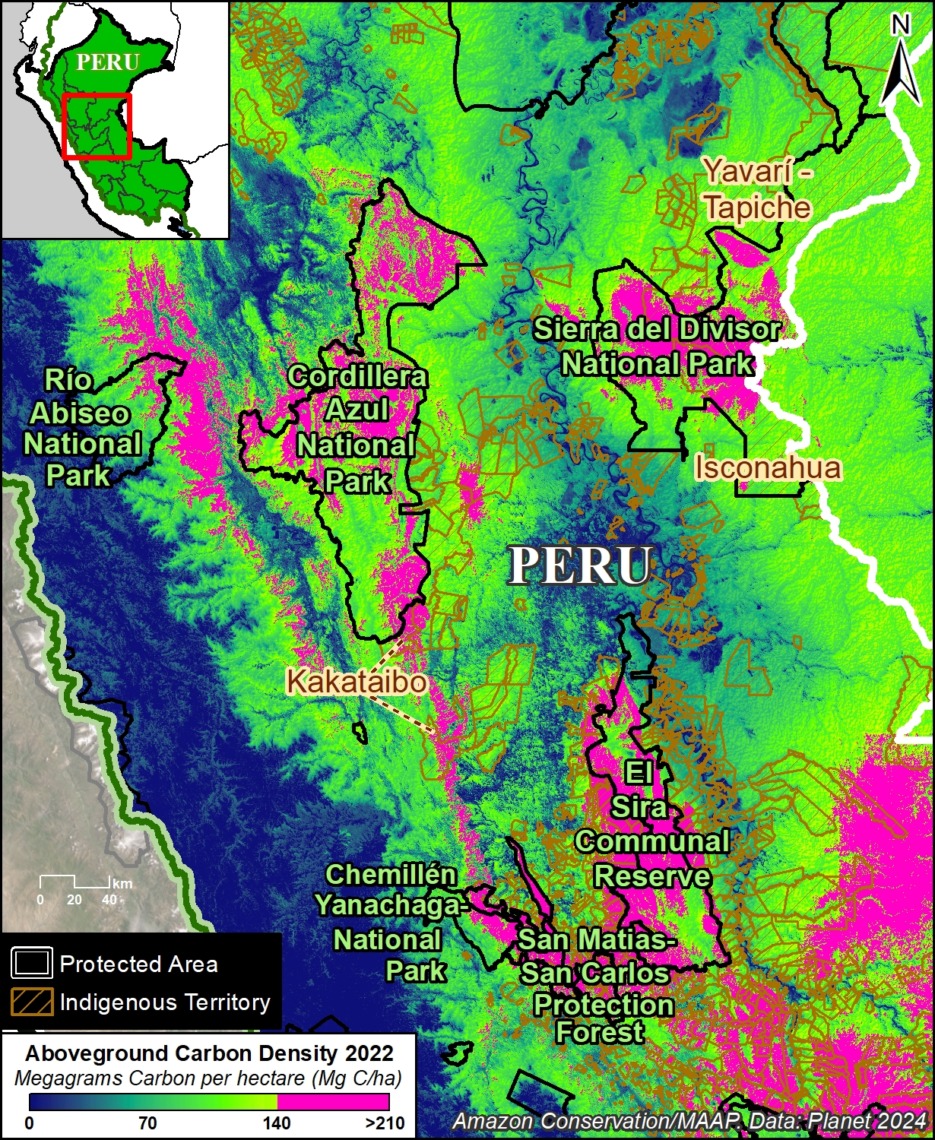

A series of recent empirical and modeling studies indicate that the southwest Amazon (including the Peruvian and Bolivian ranges of the tropical Andes) is the major moisture sink – the area where precipitation is most dependent on moisture recycling (Boers et al. 2017, Zemp et al. 2017, Weng et al. 2018, Staal et al. 2018, Sierra et al. 2022). In fact, tree-transpired rainfall is greater than 70% in this region (Staal et al. 2018, Weng et al. 2018).

Given its dependence on transpiration-driven precipitation, the impact of a reduction in rainfall from cascading moisture recycling is predicted to be greatest in the southwest Amazon (Zemp et al. 2017, Weng et al. 2018, Staal 2018, Sierra et al. 2022, Beveridge 2024). Indeed, the southwest Amazon forest may enter the bioclimatic equilibrium of savannas following projected extensive Amazon deforestation scenarios (Zemp, 2017). Forests in the northwest and Guyana Shield are also relatively dependent on forest-rainfall cascades (Hoyos et al 2018; Staal et al. 2018).

To precisely identify the most vulnerable areas in the Amazon to disruptions of transpiration-based moisture recycling in a spatially explicit manner, we merged two key studies featuring spatially explicit model outputs (Weng 2018, Staal 2018). These studies cover data for the dry season (Staal 2018) and yearly (both dry and wet seasons) (Weng 2018).

Weng 2018 identifies “sensitive areas,” defined as areas having more than 50% of rainfall coming from Amazonian evapotranspiration (representing the 98th percentile of the highest sensitivity to Amazonian land use change). Staal 2018 estimates the effect of Amazon tree transpiration on Amazon forest resilience. We selected the areas with the highest resilience loss (0.8 and higher), quantified as the fraction of resilience that would be lost in the absence of tree transpiration by Amazonian trees.

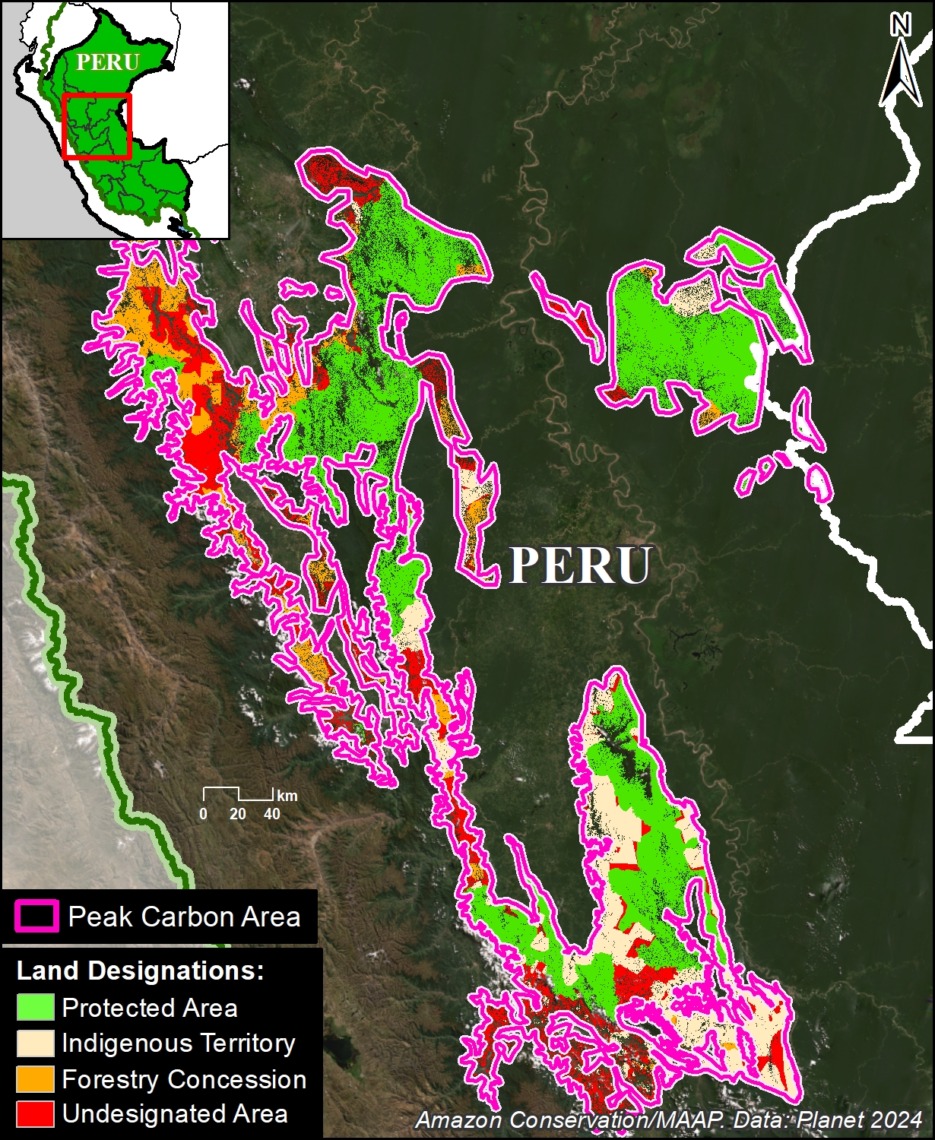

Figure 2 illustrates the merged dataset, which we refer to as “merged sensitive areas.” Notably, both studies concur that the most vulnerable areas are located in the southwest Amazon, spanning the lowlands of only two of the nine countries of the Amazon Basin: Peru and Bolivia. This merged sensitive area covers a 1,750-kilometer-long swath along the Peruvian and Bolivian Andes. In this merged data map, we include Manu National Park as a reference point, located roughly in the middle of the sensitive areas.

Weng et al. identified higher elevation areas of the Andean-Amazon transition area in both Peru (Junín, Cusco, and Puno regions) and Bolivia, while Staal et al (2018) identified slightly lower elevation areas in this same range. These regions are consistent with predicted areas of higher rainfall reduction due to deforestation (Sierra et al. 2022). Also, note that Staal indicates an additional area in the Venezuelan Amazon.

Although, as noted above, forests in the northwest and northeast (Guyana Shield) are also relatively dependent on forest-rainfall cascades, the forests of the southwest are the most dependent, likely given their location at the far end of the Atlantic-Amazon-Andes pathway.

3. Moisture flows to sensitive areas (by season)

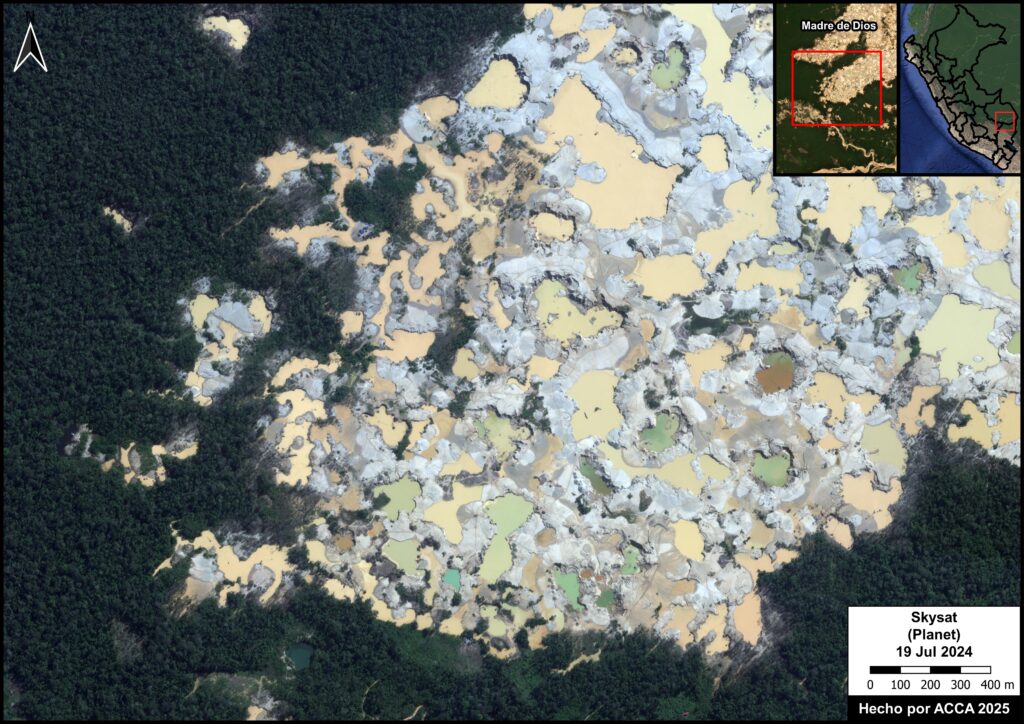

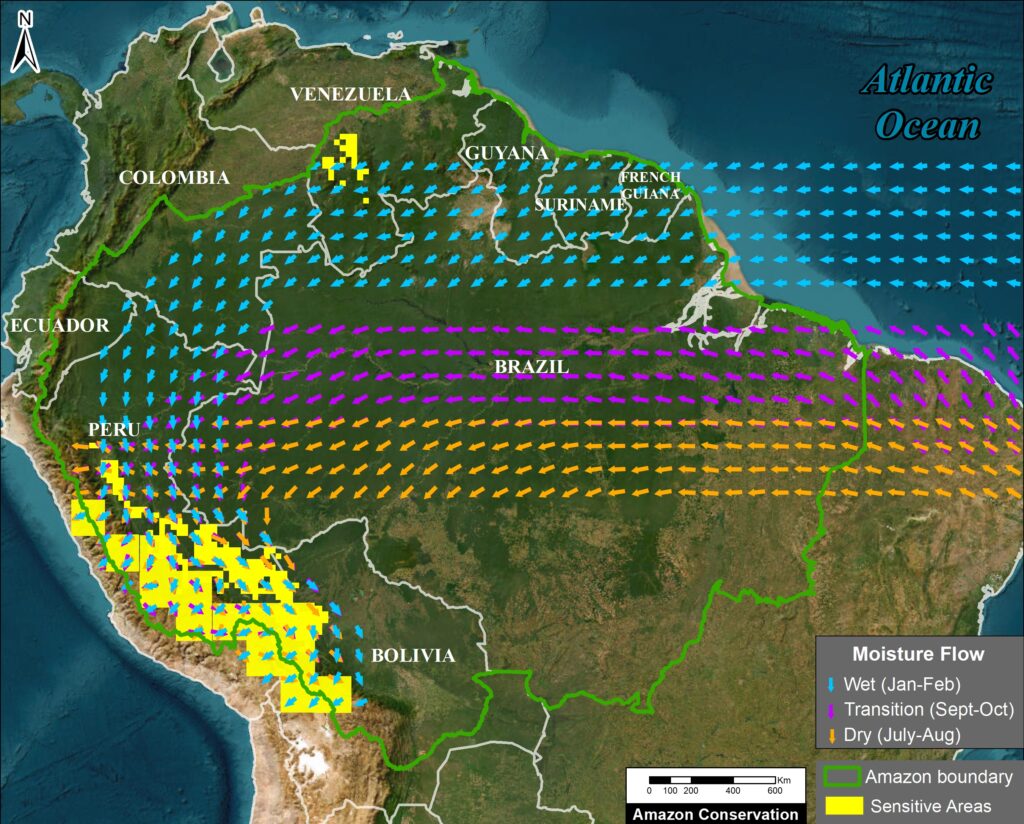

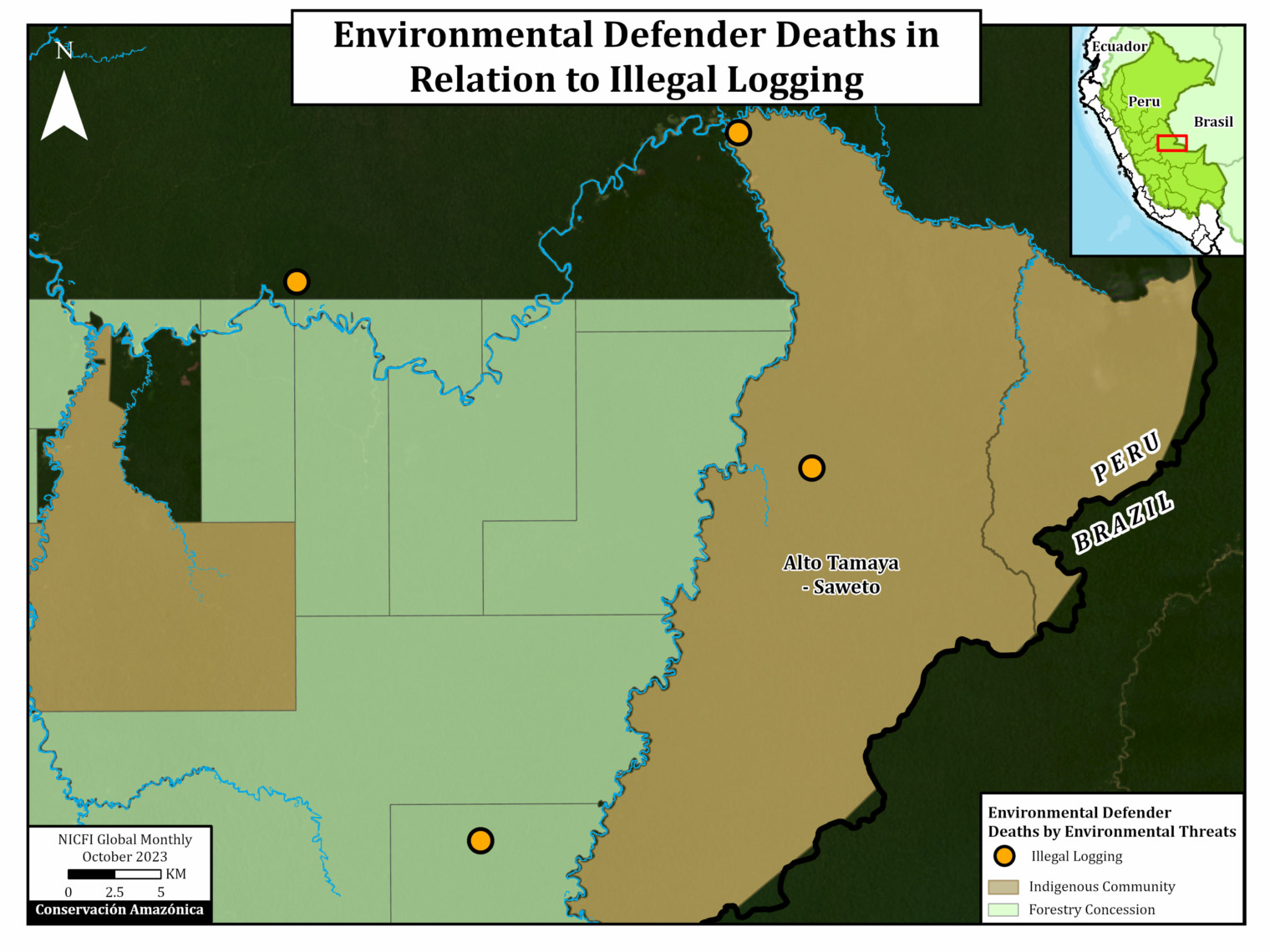

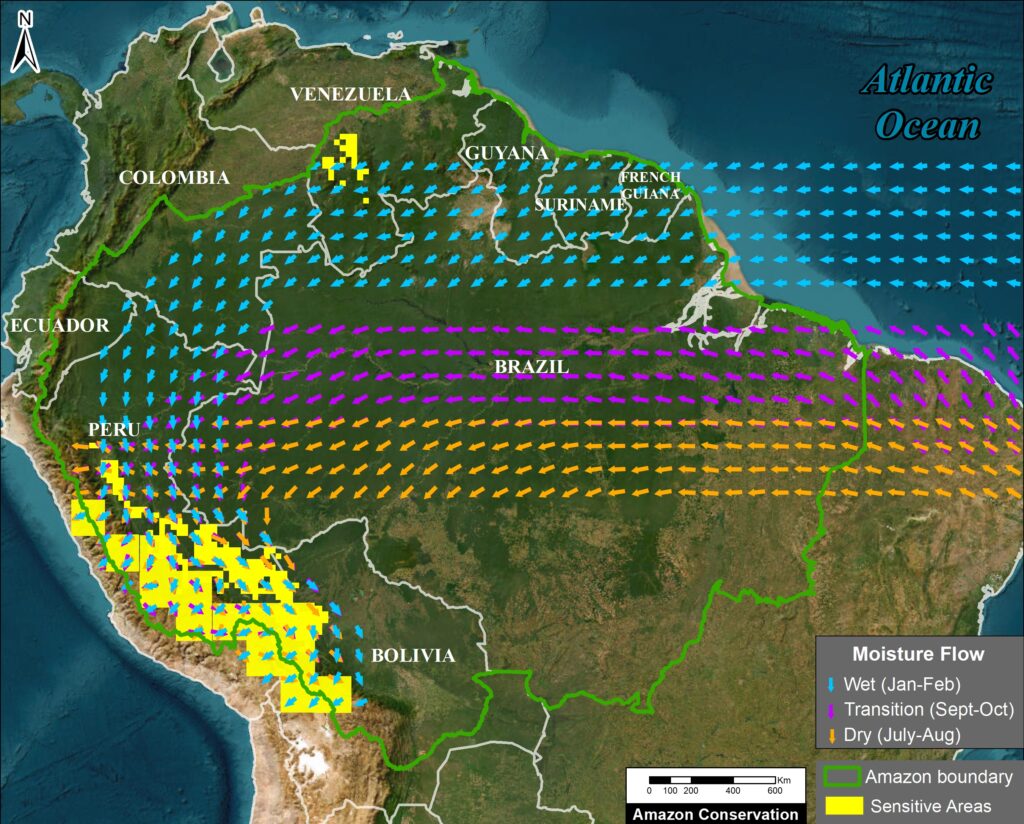

Figure 3. Amazon moisture flows by season relative to sensitive areas in the southwest Amazon. Data: ERA5, ACA/MAAP

Given the reliance of western, especially southwest, Amazon forests on cascading moisture recycling, a key challenge is to identify the most important moisture source areas in the eastern Amazon. In this respect, the literature provides a less definitive answer, likely because the moisture recycling routes change with seasons, in contrast to the long-term path of the aerial rivers that represent overall preferential pathways (Arraut 2012, Staal 2018, Weng et al. 2018).

We correlate the merged sensitive areas in the southwest Amazon with their respective moisture source areas by back-tracking the moisture flows upwind. This component of the work was inspired by the precipitation-shed concept, defined here as the terrestrial upwind surface areas providing evapotranspiration to a specific area’s precipitation (Keys et al. 2012, Weng et al. 2018).

We determined that analyzing all three major seasons is essential because of the major seasonal variability (Staal et al, 2018) and that each plays a key role in the stability of the rainforests: During the wet season, nearly 50% of total annual precipitation falls over the region, and these wet periods recharge Amazonian groundwater reserves vital for sustaining forest transpiration rates during dry months (Miguez-Macho and Fan 2012, Sierra et al 2022). During the dry season, moisture recycling processes are particularly important to ensure that some of the limited precipitation reaches the western Amazon (Beveridge et al, 2024). Tree-transpired rainfall then peaks during September to November, when large parts of the Amazon are at the end of the dry season and transitioning to the wet season (Zanin et al., 2024).

To map the pathway of moisture flow between the western Amazon merged sensitive areas and their eastern moisture sources, we utilize moisture flow data from the ERA5 reanalysis (Hersbach 2023). Specifically, we merged vertically integrated data for both northward and eastward water vapour flux. We chose data from 2022 as a recent year not heavily influenced by extreme weather events such as El Niño or drought (Espinoza et al., 2024). For 2022, we downloaded and analyzed the moisture flow data for three separate time periods: January-February (representing the wet or monsoon season), July-August (dry season), and September-October (dry-to-wet transition season).

The results for all three seasons are illustrated in Figure 3, where the arrows represent the ERA5 reanalysis moisture flow data from the Atlantic Ocean to the merged sensitive areas in the southwest Amazon.

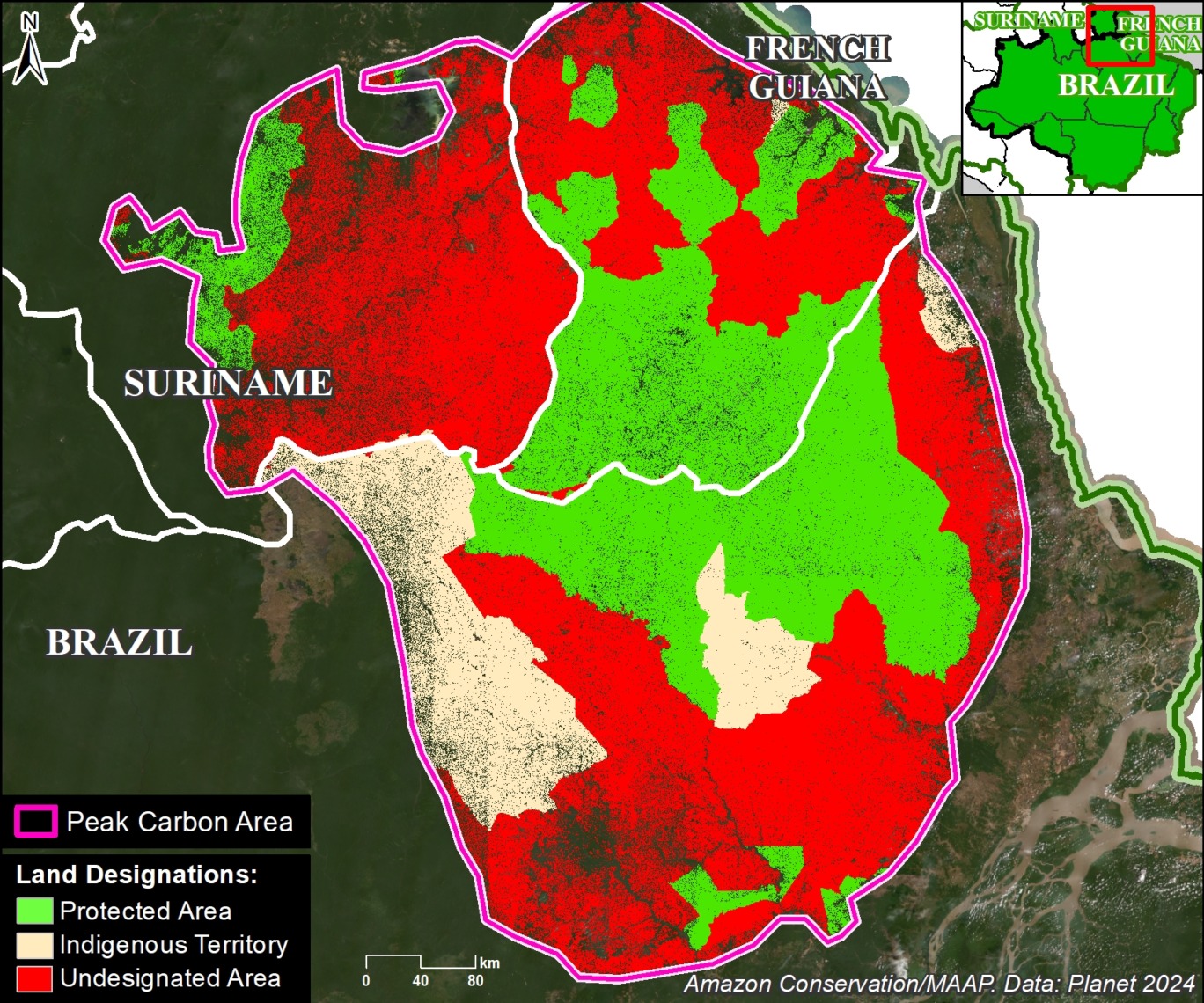

Note that in the wet season (January-February), moisture flows from the Atlantic Ocean over the northeast Amazon (northern Brazil, French Guiana, Suriname, Guyana, and Venezuela) before taking a major southern turn (arc) through the southeast Colombian Amazon and northern Peru before reaching the Sensitive Areas. This general pattern is consistent with other studies focused on the wet season (Arraut 2012, Boers 2017, Sierra et al. 2022) and year-round (Weng et al. 2018).

In contrast, in the dry (July-August) and transition (September-October) seasons, the moisture flows from the Atlantic Ocean further south across the central Brazilian Amazon, and has a less pronounced arc near the border with Peru. Specifically, the dry season pattern is consistent with other studies focused on the dry season (Arraut 2012, Staal 2018, Zemp 2017 NC). Note that the transition season flow is located between the wet season to the north and the dry season to the south.

For all three seasons, we emphasize that the entire trajectory from east to west is important for conservation regarding cascading moisture recycling. That is, the farthest away areas in the east represent the full cascading trajectory, while the closest areas in the west exert the strongest direct influence (Weng et al. 2018).

While moisture recycling covers a vast area from east to west, much of the tree-induced rainfall in the southwest Amazon is transpired nearby (Stall 2018). That is, areas exerting the strongest and most efficient influence on the southwest Amazon are located just upwind, in the central-west Amazon (Weng 2018; Wongchuig et al., 2023). In sum, extensive forest loss anywhere along the cascading moisture pathway from the eastern to the western Amazon, far or near, may affect transpiration-based precipitation in the western Amazon, adding to its sensitivity.

The overall annual pattern, accounting for all three seasons, could then be described as aerial rivers. As indicated by Weng et al. (2018), this mostly matches the pattern of the wet season.

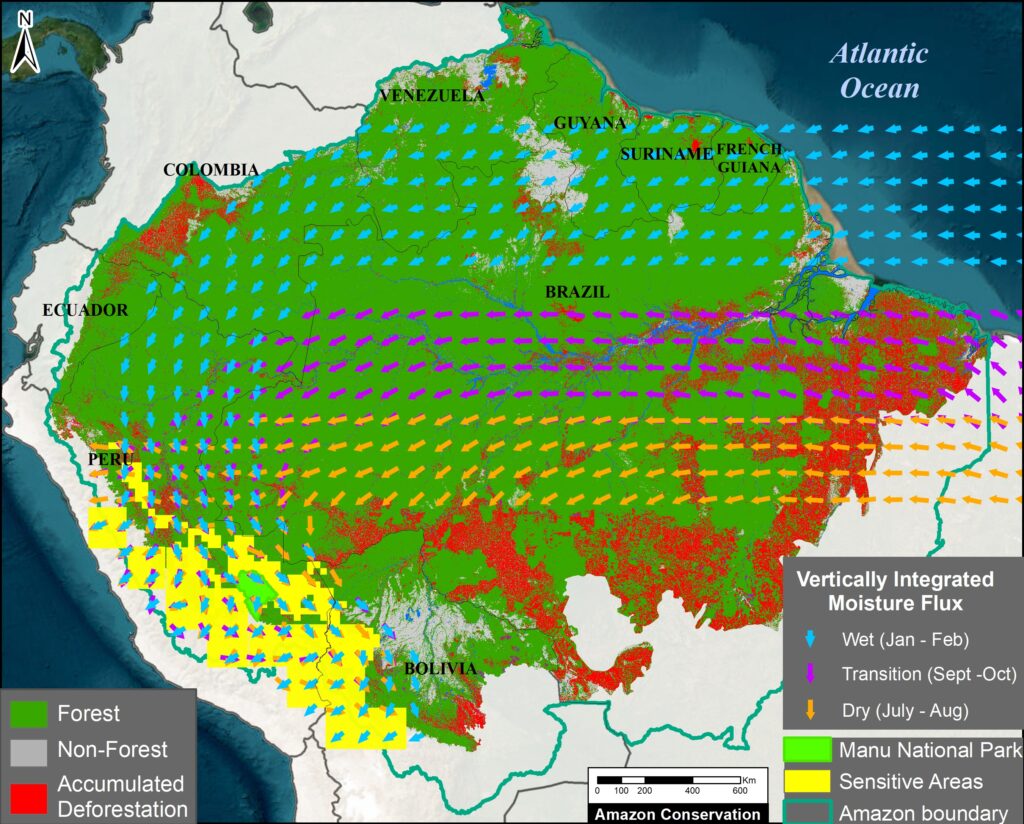

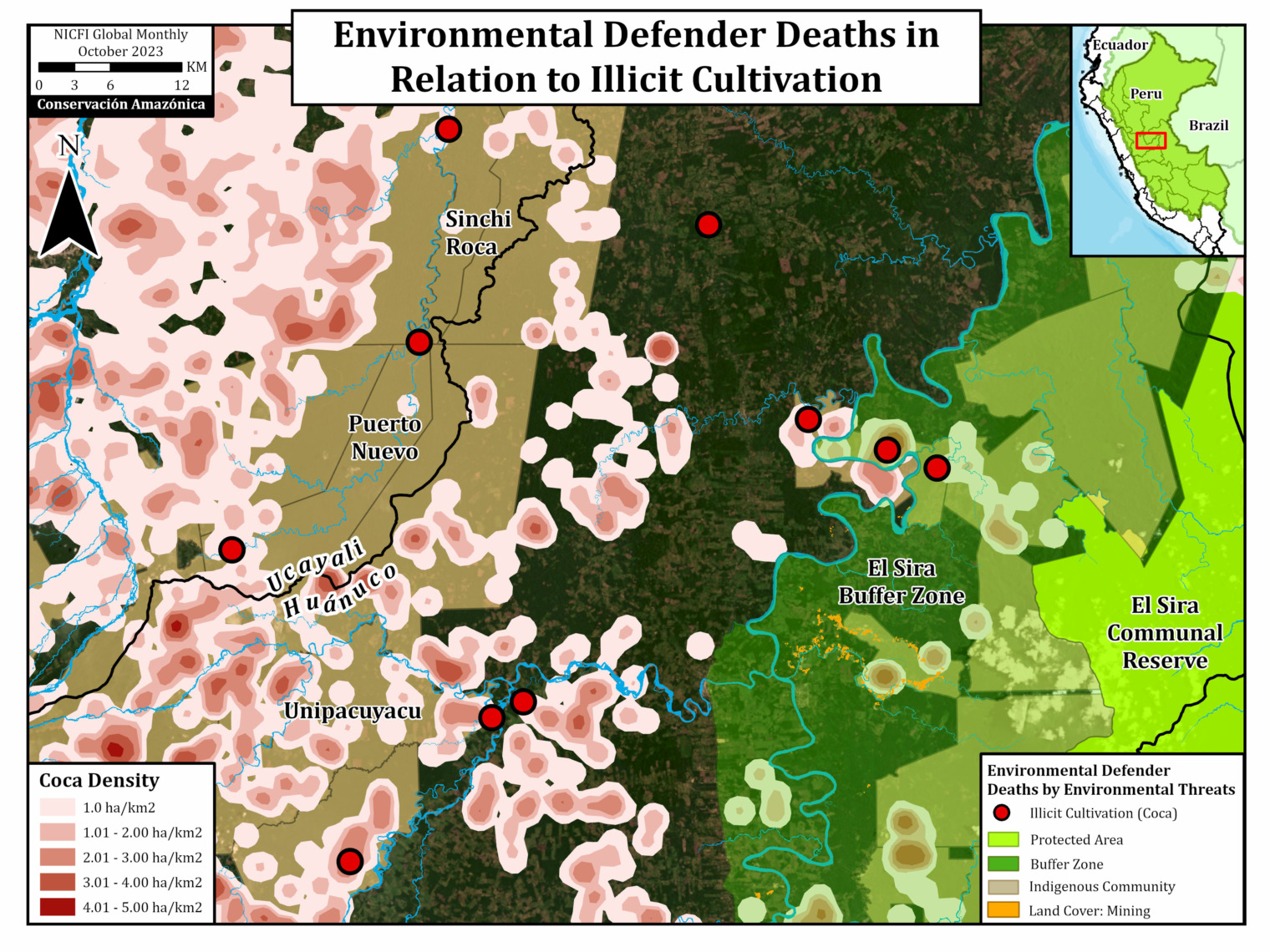

Figure 4. As in Figure 3, plus forest cover. Data: ERA5, Amazon Conservation/MAAP

For additional context, Figure 4 incorporates current land classification broken down into three major categories based on satellite imagery analysis: Forest, Non-forest (such as savannah), and accumulated Deforestation areas (as of 2022).

For January-February (wet season), note that much of the moisture flow crosses the continuous primary forest of the northern Amazon. That is, the moisture crosses predominantly non-deforested areas of northern Brazil, French Guiana, Suriname, Guyana, Venezuela, southeast Colombia, and northern Peru.

In contrast, the moisture flows for July-August (dry season) and September-October (transition season) cross several major deforestation fronts in the central Amazon, particularly during the dry season.

During the critical dry-to-wet transition season, the role of the local area’s tree evapotranspiration is especially important. The southern Amazon presents lower overall evapotranspiration values (Fassoni-Andrade 2021; Zanin et al., 2024). Due to the greater access of forest roots to deep soil water, however, evapotranspiration over forested areas is higher than croplands/grasslands during this time (von Randow et al. 2004). Since, during this transition season, the moisture transport to the southwestern Amazon passes over large deforested areas, the conservation of the remaining forest along this pathway is critical.

In addition, recent studies show that the main patterns of moisture flux can be altered at a continental scale due to deforestation (Commar et al., 2023; Sierra et al., 2023). As a result, reduced moisture transport from the Atlantic to the continent and delays in the onset of the wet season may occur in the future due to Amazon deforestation and climate change (Agudelo et al., 2023).

Conclusion

Above, in this initial technical report, we merged three key points that are critical to understanding the tipping point concept in the Amazon.

First, we presented an overview of aerial moisture flows originating from the Atlantic Ocean and then moving and recycling from the eastern to the western Amazon. Second, we identified the “sensitive areas” that are the most vulnerable to deforestation-caused disruption of moisture recycling, mostly located in the western Amazon (Peru and Bolivia). Third, we relate these sensitive areas in the west to their respective eastern key source areas for moisture for each of the three Amazonian seasons: wet, dry, and transition.

Incorporating updated land-use data, we found important differences by season. For the wet season, much of the moisture flow crosses the continuous primary (non-deforested) forests of the northern Amazon. For the dry and transition seasons, however, the moisture flow must cross several major deforestation fronts mainly located in the central Amazon.

Thus, an important contribution of this work is to reveal that, contrary to the common perception that the tipping point is a single Amazon-wide event, certain parts of the Amazon are more vulnerable than others. Most notably, the southwestern Amazon (Peru and Bolivia) is most vulnerable to a possible tipping point, particularly stressed by disrupted dry season moisture flows over major deforestation fronts.

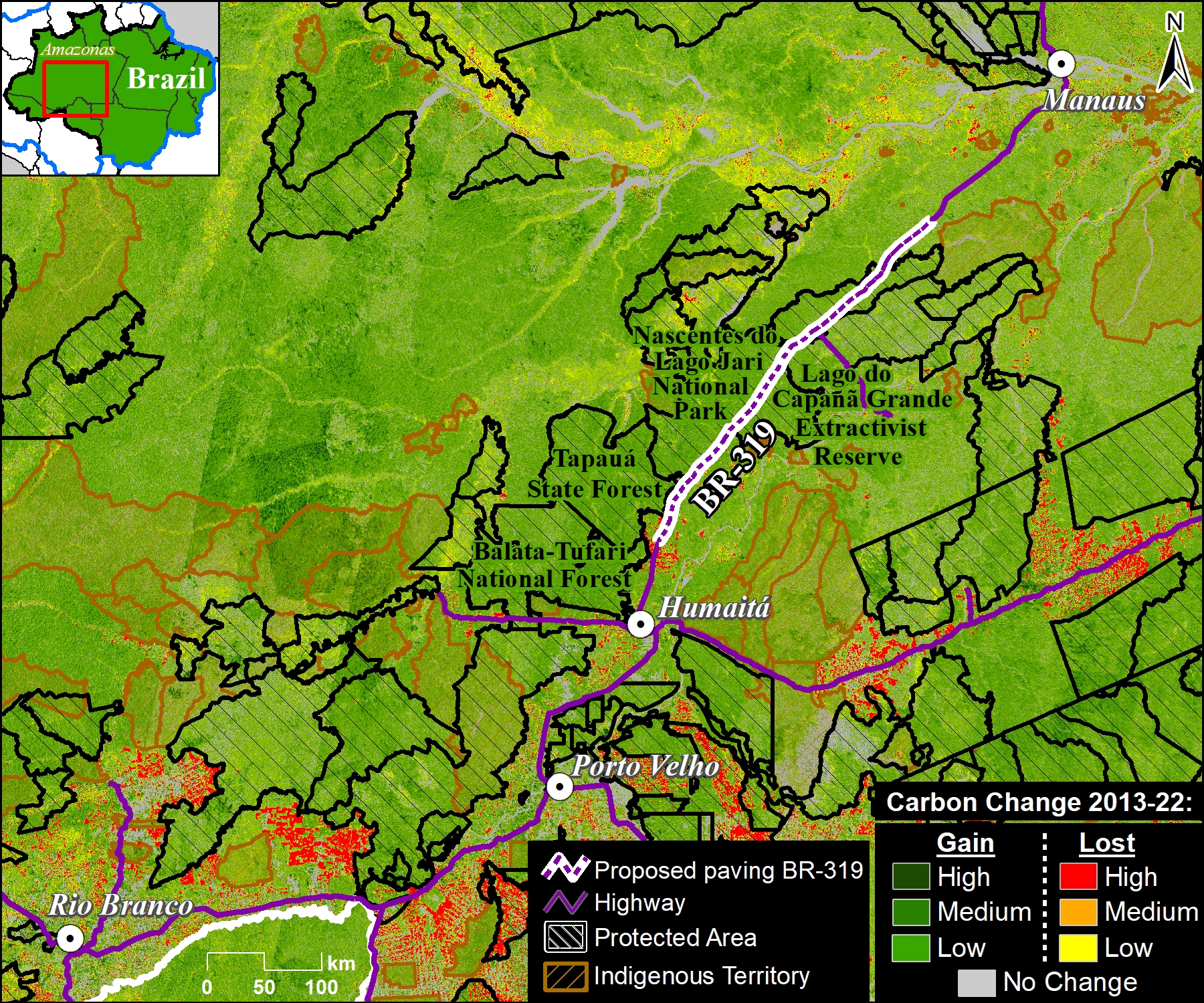

We will soon build off of these results in an upcoming policy-focused report that presents the major implications of the maintenance of aerial moisture flows for conservation. This analysis will include how to identify key conservation areas for each season based on the key concept of maintaining cascading moisture flow to the sensitive areas, in relation to protected areas, Indigenous territories, and major road networks. It will also reveal several policy implications that require urgent attention and new approaches to national governance and international cooperation. For example, It considers the implications of planned roads (most notably BR-319) and fortifying existing conservation areas and creating new ones in undesignated public lands.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Leo Model Foundation.

We thank the following colleagues for datasets and/or comments on earlier versions of the report:

Wei Weng

Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research

Potsdam, Germany

Arie Staal

Assistant Professor

Environmental Sciences

Copernicus Institute of Sustainable Development

Utrecht University

Juan Pablo Sierra

Institut des Géosciences de l’Environnement,

Université Grenoble Alpes, IRD, CNRS,

Grenoble, France

Jhan-Carlo Espinoza

Directeur de Recherche, Institut de Recherche pour le Developpement (IRD)

IGE Univ. Grenoble Alpes, IRD, CNRS (UMR 5001 / UR 252) – France

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. Lima – Peru

Co-chair of ANDEX: A regional Hydroclimate Initiative for the Andes – GEWEX

Coordinator of the AMANECER Project (Amazon-Andes Connectivity)

Clara Zemp

University of Neuchâtel

Corine Vriesendorp

Director of Science

Conservación Amazónica – Peru (ACCA)

Federico E. Viscarra

Science Officer

Science Panel for the Amazon

Daniel Larrea

Director of the Science & Technology Program

Conservación Amazónica – Bolivia (ACEAA)

Citation

Finer M, Ariñez A, Sierra JP, Espinoza JC,, Weng W, Vriesendorp C, Bodin B, Beavers J (2025) The Amazon Tipping Point – Importance of Flying Rivers Connecting the Amazon. MAAP: 232.

Literature Cited

Agudelo, J., Espinoza, J.C., Junquas, C., Arias, P. A., Sierra, J. P., Olmo, M. E (2023) Future projections of low-level atmospheric circulation patterns over South Tropical South America: Impacts on precipitation and Amazon dry season length. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres.

Beveridge et al (2024) The Andes–Amazon–Atlantic pathway: A foundational hydroclimate system for social–ecological system sustainability. PNAS 121 (22) e2306229121

Boers N, Marwan N, Barbosa HM, and Kurths J. (2017) A deforestation-induced tipping point for the South American monsoon system. Scientific reports, 7(1), 41489.

Brando PM, Barlow J, Macedo MN, Silvério DV, Ferreira JN, et al (2025) Tipping Points of Amazonian Forests: Beyond Myths and Toward Solutions. Annual Review of Environment and Resources. Vol. 50.

Commar, L.F.S., Abrahão, G.M., & Costa, M.H. (2023) A possible deforestation-induced synoptic-scale circulation that delays the rainy season onset in Amazonia. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 044041.

Delphine Clara Zemp, Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, Henrique M. J. Barbosa, Marina Hirota, Vincent Montade, Gilvan Sampaio, Arie Staal, Lan Wang-Erlandsson & Anja Rammig (2017) Nat Comms 8: 14681

Encalada A.C., Adalberto L. Val, Simone Athayde, Jhan Carlo Espinoza, Marcia Macedo, Mirian Marmontel, Guido Miranda, Maria Tereza Fernandez Piedade, Tiago da Mota e Silva & Julia Arieira (2021) Conserving the Amazon’s freshwater ecosystems’ health and connectivity. SPA Policy Brief.

Espinoza JC., Jimenez J.C., Marengo J.A. Schongart J., Ronchail J., Lavado-Casimiro W. Ribeiro JVM (2024) The new record of drought and warmth in the Amazon in 2023 related to regional and global climatic features. Sci Rep 14, 8107.

Fassoni-Andrade, A. C., Fleischmann, A. S., Papa, F., Paiva, R. C. D. d., Wongchuig, S., Melack, J. M., et al. (2021). Amazon hydrology from space: Scientific advances and future challenges. Reviews of Geophysics, 59, e2020RG000728.

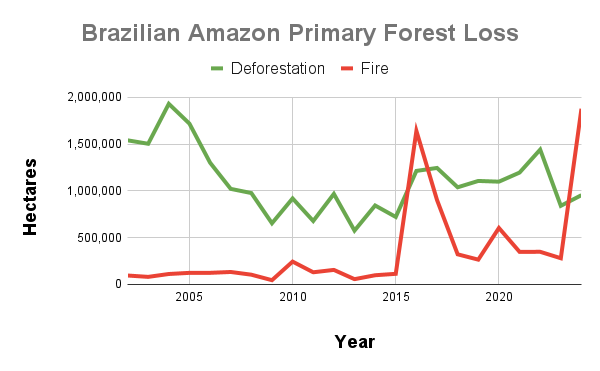

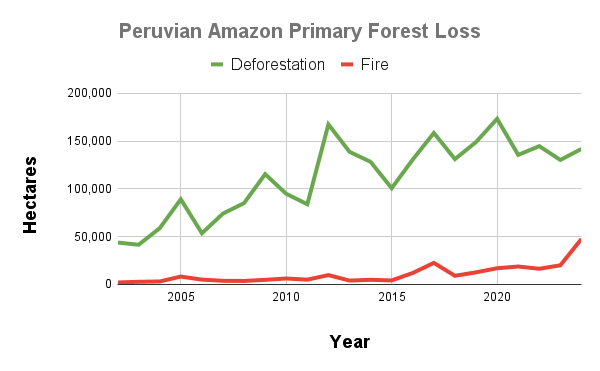

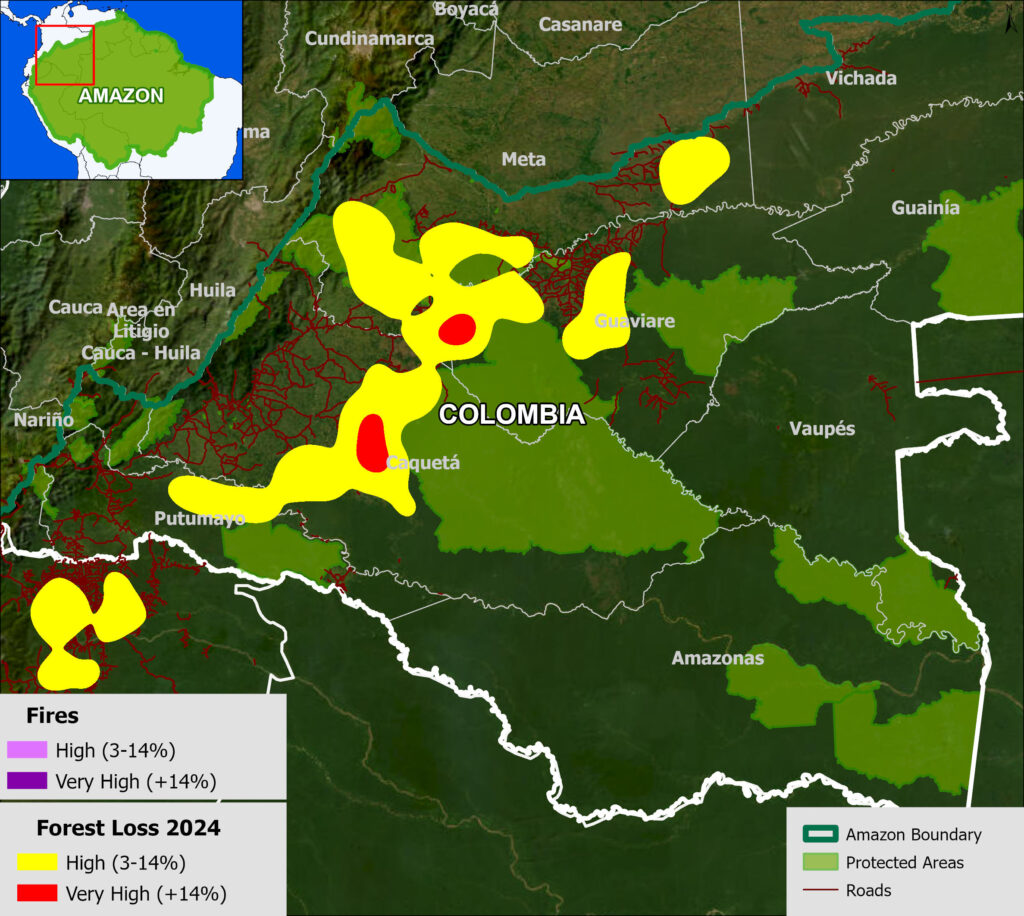

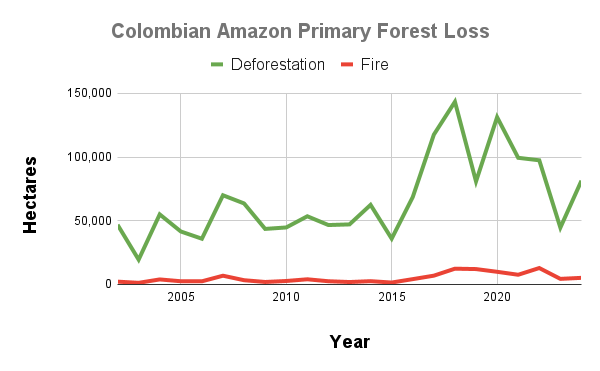

Finer M, Ariñez A, Mamani N, Cohen M, Santana A (2025) Amazon Deforestation & Fire Hotspots 2024. MAAP: 229.

Flores, B.M., Holmgren, M (2021) White-Sand Savannas Expand at the Core of the Amazon After Forest Wildfires. Ecosystems 24, 1624–1637.

Flores et al. (2024) Critical transitions in the Amazon forest system. Nature, 262 (555–564).

Franco et al. (2025) How climate change and deforestation interact in the transformation of the Amazon rainforest. Nature Communications 16:7944.

Hersbach, H., Bell, B., Berrisford, P., Biavati, G., Horányi, A., Muñoz Sabater, J., Nicolas, J., Peubey, C., Radu, R., Rozum, I., Schepers, D., Simmons, A., Soci, C., Dee, D., Thépaut, J-N. (2023): ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS).

Hoyos, F. Dominguez, J. Cañón-Barriga, J. A. Martínez, R. Nieto, L. Gimeno & P. A. Dirmeyer (2018) Moisture origin and transport processes in Colombia, northern South America. Climate Dynamics. Volume 50, pages 971–990

Josefina Moraes Arraut, Carlos Nobre, Henrique M. J. Barbosa, Guillermo Obregon, and José Marengo (2012) Aerial Rivers and Lakes: Looking at Large-Scale Moisture Transport and Its Relation to Amazonia and to Subtropical Rainfall in South America. Journal of Climate 25 (2):543-556.

Keys, P. W., Van Der Ent, R. J., Gordon, L. J., Hoff, H., Nikoli, R., and Savenije, H. H. G. (2012) Analyzing precipitation sheds to understand the vulnerability of rainfall dependent regions, Biogeosciences, 9, 733–746.

Lovejoy T. & Nobre C. (2018) Amazon tipping point. Science Advances, 4(2)

Lovejoy T.E., C. Nobre (2019) Amazon tipping point: Last chance for action. Sci. Adv. 5, eaba 2949.

Marengo, J. , Cunha, A. , Espinoza, J.C. , Fu, R. , Schöngart, J. , Jimenez, J. , Costa, M. , Ribeiro, J. , Wongchuig, S. and Zhao, S (2024) The Drought of Amazonia in 2023-2024. American Journal of Climate Change, 13, 567-597.

Martinez J.A. and Dominguez F. (2014) Sources of Atmospheric Moisture for the La Plata River Basin. 27 (17) 6737–6753.

Miguez-Macho G, Fan Y (2012) The role of groundwater in the Amazon water cycle: 1. Influence on seasonal streamflow, flooding and wetlands. J Geophys Res Atmos.

Molina, R. D., Salazar, J. F., Martínez, J. A., Villegas, J. C., & Arias, P. A. (2019). Forest-induced exponential growth of precipitation

along climatological wind streamlines over the Amazon. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 124, 2589–2599.

Nehemy MF et al. (2025) Embolism resistance supports the contribution of dry-season precipitation to transpiration in eastern Amazon forests. PNAS 122: 33.

Qin, Y., Wang, D., Ziegler, A.D. et al. (2025) Impact of Amazonian deforestation on precipitation reverses between seasons. Nature 639, 102–108.

Ruiz-Vásquez M. Arias PA., Martinez JA., Espinoza JC. (2020) Effects of Amazon basin deforestation on regional atmospheric circulation and water vapor transport towards tropical South America. Climate Dynamics.

Sierra, J.P., Junquas, C., Espinoza, J.C., Segura, H., Condom, T., Andrade, M., Molina-Carpio, J., Ticona, L., Mardoñez, V., Blacutt, L., Polcher, J., Rabatel, A., Sicart, J. E. (2022) Deforestation Impacts on Amazon-Andes Hydroclimatic Connectivity. Climate Dynamics.

Sierra, J.P., Espinoza, JC., Junquas, C. Wongchuig S., Polcher J., Moron V., Fita L., Arias PA., Schrapffer A., Pennel R. (2023) Impacts of land-surface heterogeneities and Amazonian deforestation on the wet season onset in southern Amazon. Clim Dyn.

Staal, A., Tuinenburg, O.A., Bosmans, J.H.C. et al. (2018) Forest-rainfall cascades buffer against drought across the Amazon. Nature Clim Change 8, 539–543.

von Randow C, Manzi AO, Kruijt B et al (2004) Comparative measurements and seasonal variations in energy and carbon exchange over forest and pasture in South West Amazonia. Theor Appl Climatol 78:5–26.

WCS (2023) High Integrity Forest Investment Initiative (HIFOR): The Science Basis

Weng W. (2019), Aerial river management for future water in the context of land use change in Amazonia

Weng, Wei, Matthias K. B. Luedeke, Delphine C. Zemp, Tobia Lakes, and Juergen P. Kropp. (2018) “Aerial and Surface Rivers: Downwind Impacts on Water Availability from Land Use Changes in Amazonia.” Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 22 (1): 911–27

Wongchuig S, Espinoza JC, Condom T, Junquas C, Sierra JP, Fita L, Sörensson A, Polcher J. 2023. Changes in the surface and atmospheric water budget due to projected Amazon deforestation: Lessons from a fully coupled model simulation, Journal of Hydrology, Volume 625.

Zanin PR, Pareja-Quispe D, Espinoza JC. (2024) Evapotranspiration in the Amazon Basin: Couplings, hydrological memory and water feedback. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology.

Zemp, D. C., C-F Schleussner, H. M. J. Barbosa, and A. Rammig. (2017) “Deforestation Effects on Amazon Forest Resilience.” Geophysical Research Letters 44 (12): 6182–90

Zemp, D. C., Schleussner, C.-F., Barbosa, H. M. J., van der Ent, R. J., Donges, J. F., Heinke, J., Sampaio, G., and Rammig, A.(2017) On the importance of cascading moisture recycling in South America, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 13337–13359, https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-14-13337-2014, 2014.